Lit Mags

Saint Andrews Hotel

by Sara Majka, recommended by A Public Space

EDITOR’S NOTE BY BRIGID HUGHES

The other day, a friend emailed wondering about a sentence from C.S Lewis: that a certain experience “makes nonsense of our common distinction between having and wanting. There, to have is to want and to want is to have.” I wonder if he might mean something like this, I wrote back, and attached “Saint Andrew’s Hotel” in reply.

The story — about an island that disappears from the map, and a boy named Peter Harville who is left stranded on the mainland — appears halfway through Sara Majka’s debut Cities I’ve Never Lived In (which Graywolf will publish as part of A Public Space Books next year), and is the surprising and perfect anchor of a collection that revolves around a woman consumed by “a feeling of being nowhere, or in someone else’s life, or between lives.”

Maybe because it first appeared in an issue of A Public Space that was full of travelers and explorers, in my memory “Saint Andrews Hotel” was a story about a lost wanderer. But reading this story again, what stayed with me were more solid moments — a woman eating a Danish, “getting to pick what she wanted, and enjoying the secrecy of her choice,” the hotel residents sharing clams at dinner. And the mood Sara creates from the unexpected combination of stoicism and will. The way she makes the distinction between having and wanting a fool’s errand. At the end of the story, Peter sits at the hotel bar (is there a better setting for the permanence of impermanence?), and for a moment what he’s lost — the island, his mother, time — having been willed back. “Will it leave me? How to make it not leave me?” The title of the collection offers a sort of answer: we are most citizens of the places we cannot be.

Brigid Hughes

Editor-in-Chief, A Public Space

Saint Andrews Hotel

Sara Majka

Share article

by Sara Majka, recommended by A Public Space

In 1963, an eleven-year-old boy named Peter Harville was committed to a state mental hospital in the western part of Maine, far from the island where he grew up. He had tried to commit suicide by cutting his wrists with his father’s coping saw, but he hadn’t made much of a mess. A pile of sawdust below the bench absorbed much of the blood. He lay on the ground watching the sawdust turn red until he realized someone had opened the door. Peter? his father asked, not moving or coming in. Peter? Are you all right? Peter noticed that his father spoke more gently than usual, and the shed felt warm and calm; for the moment he was happy. The crack in the door let in light glittery with dust.

The father ran to call the doctor, then walked stiffly up the grassy slope in the backyard to get his wife. She was clipping laundry at the top of the hill. She — Helen — wondered what was wrong with her husband’s mouth, the way it moved as if with a life of its own, as if he was having spasms.

The next week she packed a bag for Peter and his father took him on the ferry, then into the Cutlass sedan that was kept in the lot on the mainland with a key under the seat for anyone on the island who had an errand to run. They were at the hospital by three. Afterward, the father checked into a hotel. He went to the bar across the street and had several pints of beer. It had been ten years since he’d spent a night off island and he spoke little, just studied the line of coasters taped to the wall behind the bar. His hands twitched on the counter. They were small-boned and fine, adept at gutting fish and killing the lambs during the summer slaughter, thinking of those lambs dangling in the walk-in no more than he thought of anything else.

In the hotel room, he took off all his clothes — the room lit in vertical lines by the blinds — and folded back the sheets, then slid inside and tried to sleep. When he got home, he didn’t say much to his wife. She listed object after object, asking if they’d let Peter keep it.

You’ll baby him, he said.

What is there left to baby? she wondered, looking around the empty house.

Sometimes I dream about him, she said to her friend Eleanor. They were hanging laundry; the wind came up the grassy slope and blew all the soft clothes on the line, the chambray shirts and white cotton sheets, her blue nightgown with lace along the neckline.

While her friend clipped, Helen stared across the sea. She felt as though she had lost something but she kept forgetting what it was, and when she remembered she couldn’t understand it. Do you suppose it’s a long trip? Helen asked, her voice sounding like it arose from a daydream. The idea had come to her over days, like a bubble expanding in the back of her mind, that it had been a mistake, that she would take the ferry, find the car, drive to the hospital, tell the doctors it had been an accident with the saw, that it wasn’t true what her husband said about Peter.

Her hand slipped, and a gust of wind took the sheet and blew it down the hill. Both women laughed and chased after it, barefoot in cotton skirts, two thirty-year-old women chasing after a sheet, then drinking instant coffee in the kitchen with a plate of crackers between them. They gossiped about the hotel where Eleanor worked as a housekeeper. She was seeing one of the men there, someone’s cousin who was going back to Boston in two weeks. She was a tall, thin, bent-backed woman with violet circles under her eyes. Helen watched her, watched the liquidness of new love — the way her talk spilled, her eyes shone, how her hands slid through the air — and thought, he’s going to leave and she’ll still be here.

One day the ferry went out to sea but the mainland never came. The captain turned back fearing he would run out of gas. He tried again the next day, but still couldn’t find the shore. In time, he took it as a matter of course, as they all did, as they forgot their desires with some relief, as the desires when they arose had been impractical, painful. One man painted in the loft of an old barn. All his canvasses were of blue trees. The islanders hung them in their living rooms, and there was something hopeful in it, as if they had kept a belief in the symbolic power of beauty.

Peter stayed in the hospital until he was twenty-one. He would have left earlier but nobody could find his parents, and the hospital had put him to use in the kitchen. When he left, he couldn’t find the island on any maps. In the place where it should have been was a sprinkle of land, most of it not much more than rocks. The most promising landmass turned out to be nothing but sandy slopes and beach grass. He was told someone had tried to start a leper colony on it years ago, but it had proved inhospitable. He traveled the coast for some time, taking on construction jobs or working the docks, looking for anything familiar.

He finally took the bus up north and got off in Portland, Maine. He stood there, a medium-sized boy with pale coloring and a slow, coltish walk. Across the street he saw an old brick building with “Saint Andrews Hotel” lettered in faded white paint. Inside, a threadbare green carpet spread across a large, mostly empty lobby. A cluster of sofas and upholstered chairs huddled at the center; several of the residents sat there. The hotel rented rooms by the night, but also long-term, and many of the people had been living there for years.

He took a room for a month. When the month was up he paid again. He liked it there; he liked to sit idly with the other residents. In the hospital, they had sat for hours on the long, narrow sun porch, everyone squished in with African Violets and end tables. All the old men leaning on canes, their eyes in the light as opaque as glass marbles. No sooner had Peter left the hospital than he found another one. How strange we are. How different we are from how we think we are. We fall out of love only to fall in love with a duplicate of what we’ve left, never understanding that we love what we love and that it doesn’t change… The way they sat on tattered velvet chairs — the old men with crooked legs and the couple arguing in sleep-starved voices and the boys, too skinny, wearing their hair in delicate shapes along their temples.

He took a job at a fish stall in the Portland Public Market and would come back with the belly of his white T-shirt — the place where he leaned against the counter — stained watery red and orange. What have you been up to, Petey? Betty would call out. She worked behind the desk, and always had shadows of mascara under her eyes, even during the morning shift.

He would shower, then return to the lobby, the low tide smell still clinging to him. The people talked lazily back and forth. A man drinking from a coffee-stained paper cup turned to him, and said, I used to have a wife from Chicago. Know what she did?

No, Peter said.

Fell in love with the butcher, the man said.

Another man said, Don’t pay him any mind.

Things went much as they had in the hospital, until one day a girl came in. She was beautiful — fourteen, fifteen, slender, knock-kneed. She used to live on the island, used to ride up and down the dirt road on her bicycle, her wispy hair flying after her. She wore a lavender skirt instead of cutoffs and her face had lost some of the boyishness, but otherwise she hadn’t changed.

No, man, someone said when Peter started to walk over. That one’ll put you in jail.

No, he said. I know her. He froze before he got to the desk. Something was wrong. He realized what it was and backed away: she should have been older than him. She should have been nearly thirty.

In the morning, he followed her from the hotel. She walked to the old port section of town, along cobblestone streets and down to the ferry terminal. She walked through the building and out into the fenced-in area where people waited. She put down her bag and stood there, a cardigan folded over her arm. She must be mistaken, he thought, standing like that in front of a boat that never left the harbor. It must have once been a nice boat, with a cream-colored canopy and dark wood accents, but the hull was leaking rust; a dozen wooden park benches had been dragged under the canopy. He thought there was no sense in it, but then an old, silver-haired man emerged from the cabin, and took the girl’s ticket. She boarded.

When Peter tried to board, the captain said, We don’t sell tickets on this end. This is the return boat.

Peter asked where it was returning to, but the captain shook his head, then tied the rope, pulled in the metal ramp, and disappeared the same way he came. Soon the engine sounded.

The next time someone from the island came, it was a friend of Peter’s father’s, an old fisherman, a drunk with a bulbous nose and gaping pores. Peter had always liked him, found something gentle in him that had been missing in his own father. As with the girl, the man hadn’t changed, hadn’t aged. Peter followed him down the hall to the bar in the corner of the old ballroom, and sat next to him. The bartender poured Peter the bottoms from old bottles of wine. The man was impressed — Helps to know people, the man said. They talked for a while. The man said he had never lived on an island, that he drove trucks for a shipping company. Always wanted a boat, though, he said. He opened his wallet and showed a slip of paper tucked inside the silky creases. He wasn’t a man for impulses, but there it was, a ticket to look at whales for the next day.

In the morning, Peter walked with him to the same ship the girl had left on. After the man boarded, Peter extended a wad of bills towards the captain, who looked at it kindly as if not understanding what Peter was showing him, but wanting to understand.

For months no one came, then a small, strong, dark-haired woman appeared. She wore a cheap-looking polyester skirt and a scallop-sleeved peach blouse. It was his mother. Like the others, she hadn’t aged. She edged around the lobby like she used to do when they went shopping on the mainland, dropping her shoulders so her body moved inward. She used to pick through shirts and speak as if annoyed with him, then hold the shirts up to his frame and purse her lips. In the hospital he would sit on the bed and look out the window, certain she would come, but she never came, that slight figure never appearing on the hill, never coming in, never explaining to the doctors and looking angry at him only to have the anger turn to relief when they got outside. Now she had come after all, but what was it? What did it mean?

She stopped at the desk, then went down the hallway, following the man who carried her bag.

He tried to get her name or room number from Betty. She’s too old for you, she said.

She reminds me of my mom, he said.

She shook her head. Sorry, she said, it’s regulations. She took a dollar from the drawer so he could buy coffees from across the street.

In the morning, his mother reappeared in clothes even more drab — a gray skirt and an ill-fitting blouse and sandals so tight that her feet squished out between the straps. She went over to the utility cart to pick out her breakfast. She hovered over the metal tray with pastries piled on doilies — the doilies reused until grease blots seeped through the paper — at last selecting a Danish with a circle of yellowed cream at the center. She ate her breakfast in a high-backed chair along the wall, eating slowly as if she were on a trip away from home for the first time, getting to pick what she wanted, and enjoying the secrecy of her choice.

Peter handed her a newspaper.

What’s this? she asked, holding it away from her.

I thought you’d like it, he said.

Thank you, but I don’t read the paper.

After his mother left the lobby, Betty bought the paper from him. She did the crossword puzzle, frowning at the paper as if it had done something to her. Do I remind you of your mom? she asked.

Not in the least, he said.

She invited him to her room after her shift for a cocktail. When he arrived, she had showered and washed off her makeup. She had spread nips on the table, and he lifted up the fanciest bottle. She gestured for him to take another. Go ahead, put them in your pockets, she said. He picked a Jack Daniels and some gin, and slid them in his pockets. She motioned for him to take more. She talked to him about something — applying to college, or a trade program. He opened a bottle and drank. She ran a hand over her face as if looking for something. You should listen, she said. You can’t stay here forever. I’d like it if you could, but you can’t.

He thought of opening another, but instead tapped his pockets, moved to the door, and said, You coming to clams?

Sure, she said. I’m coming, but —

When he walked out to the hall, his mother was walking past. Are you finding everything to your liking? he asked, falling into step with her.

Everything is fine, she said.

There are brochures in the lobby with some attractions, he said. If there is anything I can do for you.

I’m quite all right.

He said, I was wondering where you’re from. She kept moving; he reached and touched her arm but she shrank from him. You remind me of someone I know is all, he said, someone I once knew. And I don’t mean to bother you. I just wanted to make sure you were having a nice time.

She stopped — they were in the lobby — and studied him. I’m from Stamford, Connecticut, she said.

Do you have a son?

A daughter.

Does she look like you, or like your husband?

Like me, she said.

Do you have a picture?

That’s enough.

She meant it to come out more lightly than it did. When she saw his pain, she asked him to show her the brochures, and she took several, even ones she had no interest in. He gave her directions to cafés and shops. He invited her to clams. She told him she would stop by, hoping she wouldn’t be able to find it.

The people at the hotel ate clams at a rundown place by the docks that had five-cent littlenecks on Tuesdays. They sat inside on tables covered with plastic gingham cloths. The back door was open, but the wind didn’t come through. The door looked onto a parking lot filled with lobster traps and rope crusted with dried-out crustaceans. Beyond that lay the harbor. From there, Helen appeared, her head turned toward the ocean, as if she hadn’t realized yet that she was inside. Peter stood, and the others stopped talking. She looked up, saw the table of scraggly people and the young man, his hair a fine sandy gold and his body shimmering with sweat. She hadn’t noticed before how different he was from the others. It occurred to her that she could take him with her, as if he could fit into her purse. She thought of her house in the development, the driveway with squares of concrete that reflected the moon.

You came, he said.

Yes, the directions were good. She sat down, keeping her purse on her lap.

No one is going to take it, he said.

She laughed. It’s just habit.

We ordered already. We would have waited, but we didn’t —

No, it’s fine — I’m glad you didn’t. Sometimes I can never find the places I need to find. She glanced at the table for a menu, but didn’t see one. She lifted an arm to flag the waitress, but he pulled her arm down. Clams, he said.

Clams?

You order clams.

What else?

Clams, Portuguese roll, ear of corn, iced tea with sugar. Just say — never mind. He looked up. The waitress had come over. She’ll have the clams, he said, and the waitress nodded and walked away. I’ll have the clams, Helen repeated. Very good choice, someone said.

When the food came they stopped talking. Chipped stoneware bowls were filled with shells the colors of seagulls, with clams so small they must have been illegal. They picked out the graying bellies with little forks, and dredged them through butter, their lips shining with the oil. The thin, waxy napkins that came in the packs of plastic silverware only blotted the oil. On the walk home — No, not home, Helen caught herself — she said to Peter, I’m glad I came.

You thought you wouldn’t be? he said, holding his arm out to see the shadow.

Yes, she said. I thought it might be strange.

But you’re glad?

I’m glad.

At the hotel bar, they had several drinks, things she wanted that he wouldn’t normally have ordered. Things mixed with cranberry juice, grapefruit, grenadine. Oh! she said, aren’t you going to eat your cherry? The cherry was at the bottom, speared to an orange by a pirate’s knife. He had never gotten a pirate’s knife before. Two cherries! she said. She’s happy, he thought. I’m happy was the next thought, trailing the first like a tail that was just beginning to wind around. The unfamiliar recognition of joy, the discomfort in it, the panic. Will it leave me? How to make it not leave me? Thinking that if he pretended it wasn’t there, it wouldn’t leave.

At the end of the bar, he saw the captain of the ferry, hunched over, one arm circling a beer. No, Peter thought. No, no, no. He turned to his mother. She was lining up swords. She looked like a little girl. He asked her how long she was staying at the hotel. She said she wasn’t sure. He asked if she was taking a boat the next day. She didn’t understand. Are you taking a boat somewhere? he said. Anywhere? Just — are you getting on a boat tomorrow?

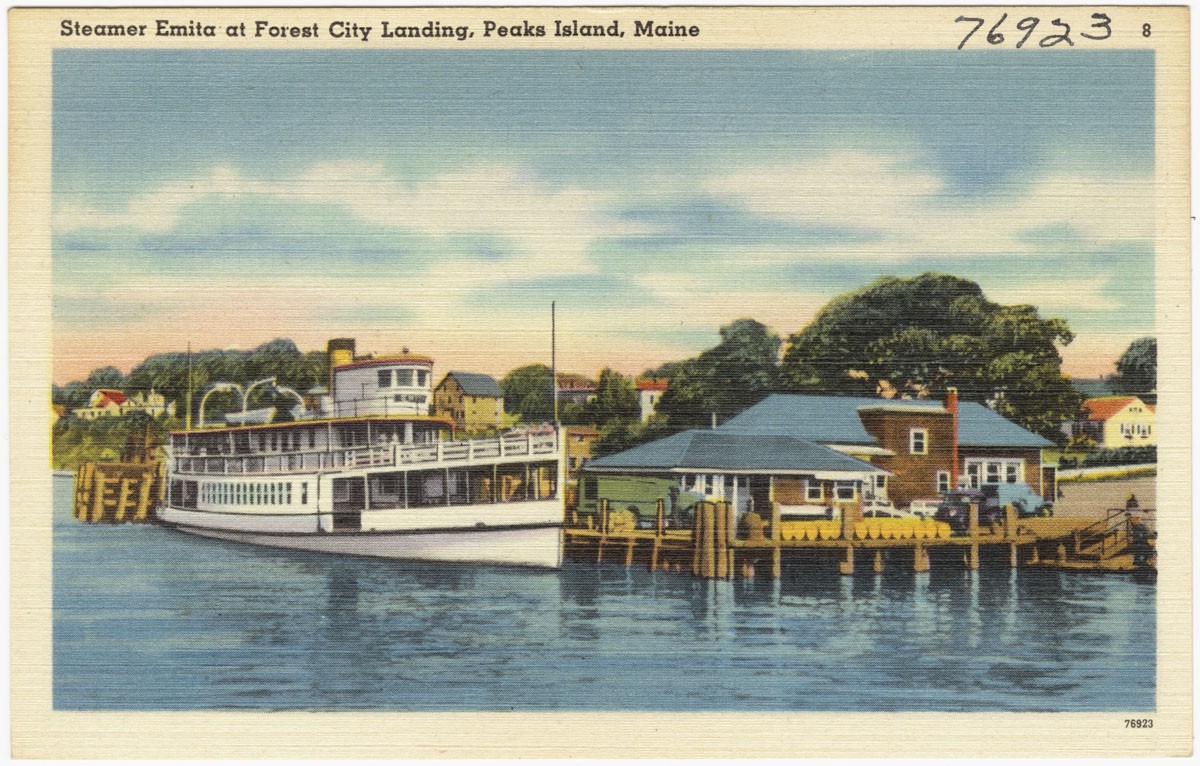

To Peaks Island, she said. It was a tourist island close to the mainland. The picture on the brochure had captivated her.

Can I come with you?

It might be better if I go alone, she said. I’ve had such little time to be alone. It sent pain through him. She saw it. She said, I don’t know you.

Do you feel like you know me? That you might have known me before?

I read paperbacks, she said. I go to restaurants and sit by the window and read.

That’s what I like to do, too.

In the morning, she stood in the lobby, holding a straw hat. He walked toward her. He could see Betty approaching him, so he walked faster. When Betty realized what he was doing, she stopped in the center of the room, under the place where a chandelier used to hang.

Outside, he lifted his mother’s bag.

I hope the person I remind you of was kind, she said.

She was always kind.

Well, there’s that at least.

When they got to the ferry building, the window where she had bought the ticket was boarded up, or she couldn’t remember where it was, or something else happened to confound them. I don’t understand, she told the captain when they got to the boat, it seems it’s just as easy to sell it here. She looked at Peter and said she would stay if he wanted that, but he handed over her bag and said to go on, that he would be there when she got back.