Books & Culture

Searching For My Immigrant Roots with W.G. Sebald

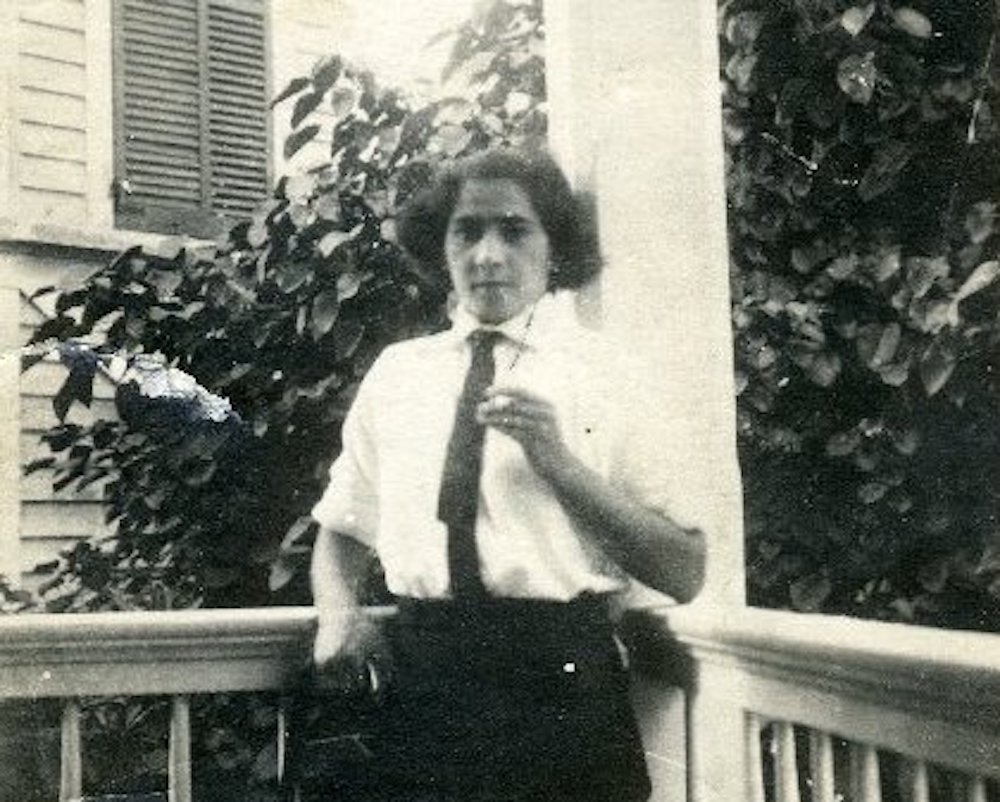

The German writer’s keen observation of displacement helped me understand my own ancestor’s journey

Two tributaries enclose the village of Wittelshofen to the east. On the Sulzach, white lilies float over deep holes in the riverbed, and trees lean over the gray surface of the water in the wind. A bridge over the Sulzach becomes Haupstraße and cuts the town in half. From there, Schulstraße leads north, past houses painted in half-hearted blues and mustard yellows. The road ends at a brown barnyard that houses the museum of local history, which appears permanently closed. A silver plaque is mounted on a stone, dedicated to Wittelshofen’s Jewish community: “They lived here in peace for 300 years.” South of Hauptstraße, an alley named after the other tributary, the Wörnitz, leads to the town’s only guesthouse. Villagers wander in to plan weddings and baptisms.

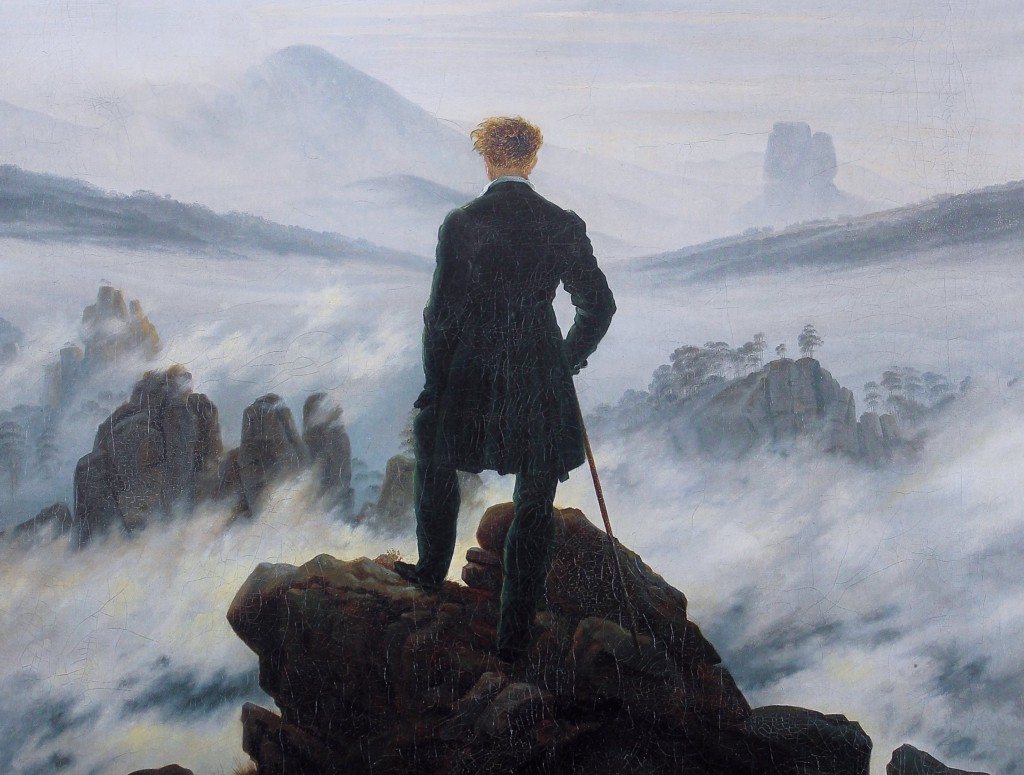

The German writer W.G. Sebald was unusually alert to these quieter displacements. In his novel Austerlitz, a boy is sent away via Kindertransport from his Jewish parents in Prague to a preacher’s family in Wales, a break that permanently destabilizes his understanding of reality. In The Emigrants, a talented teacher who briefly fought in Hitler’s army kills himself. The Holocaust is omnipresent in Sebald’s work, like it is in Germany, but mostly as a kind of hollow center, a void at whose edge we can only stand through the stories of people who weren’t there. Sebald traces around the outside of history, breaking our hearts as we slowly perceive the shape of the thing. Reading him, I got to know intimately the rifts history caused in his characters’ semi-fictional lives. I went to Wittelshofen hoping to learn my own family’s history as closely.

Reading Sebald, I got to know intimately the rifts history caused in his characters’ semi-fictional lives. I went to Germany hoping to learn my own family’s history as closely.

I had been assigned to cover productions of Wagner’s Parsifal and Lohengrin at the Bayreuth Festival — Yuval Sharon had recently become the first American and the second Jew to direct an opera there — and, on my day off, my husband and I drove the three hours from Bayreuth to Wittelshofen, past Nuremberg and Ansbach, through a storm that turned the sky metallic silver. Josef Oestreicher, my great-great-great-grandfather, was born there in the Schmalzgasse in September 1833, and left for America as a teenager. Would there be any signs of him or his family, or only what Sebald, in The Rings of Saturn, called “traces of destruction that reach into the distant past”? Did my family have any connection left to this secretive place?

My grandmother gave me a copy of Oestreicher’s memoirs. In his time, Wittelshofen had a population of 500, evenly divided between Protestants and Jews. Oestreicher went to school, worked on his family’s farm, and spent his free time fishing and shooting primitive guns. His family was prosperous — his father, Abraham Isaac, owned a library of Hebrew books — but large, and by the time Oestreicher was a teenager, his mother decided he would need to leave. “She could see no promise in the future there for me,” he wrote.

At four o’clock in the morning on October 4, 1850, Oestreicher and his sister Ida started for America. Their journey took them to Feuchtwang, Würzburg, Aschaffenburg, Frankfurt, Mainz, Rotterdam, and finally Le Havre, where they boarded a ship for New York City. The conditions during the month-long journey were so unpleasant that a monk attempted suicide by jumping overboard. (He was saved by the crew, but they warned him they wouldn’t repeat the favor if he tried again.) Josef and Ida arrived on November 21. They watched as the passengers, angry with their treatment at the hands of the ship’s first mate, formed a mob and “beat him till they nearly killed him.”

The conditions during the month-long journey were so unpleasant that a monk attempted suicide by jumping overboard.

Dark American realities soon replaced German ones in Austrian’s mind. After a year peddling cheap jewelry on the streets of Detroit, Oestreicher reached a tiny town in Wisconsin called La Pointe. A family friend had a store there and hired him as a clerk. The village was made up of a handful of “white Americans, 50 Canadian Frenchmen who were married to squaws, and a number of full-blooded Indians.” Oestreicher complained that his brother, “to his own detriment and loss, often trusted needy and hungry Indians.” When a young Native American man stole food from the store to feed his family, he was thrown in jail and nearly succeeded in hanging himself. Exposure to cruelty has a way of misaligning the human psyche. The narrator of Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn journeys through the English countryside, seeing latent evil everywhere. He finally suffers from mental collapse, unable to perceive the porous border between history and present.

It’s not clear from his memoirs at what point Josef Oestreicher became Joseph Austrian. He accepted his new name, in a certain sense a new personality, with the casual innocence of the young immigrant. America became his predominant frame of reference. Sebald, in The Emigrants, describes a similar process whereby one reality extinguishes another. Ambros Adelwarth, the narrator’s uncle from a small German village, becomes butler and possible lover to the scion of a rich Jewish New York banking family, Cosmo Solomon. Together they take a trip through what was then Palestine. Adelwarth wrote in his journal, “In the places where only the shadows of the five punished cities of the plain, Gomorrah, Bela, Sodom, Zeboim and Admah, can be perceived, now bay bushes, crown flowers and mimosoideae grew from the riverbeds, like in Florida.” When, late in life, Joseph Austrian returned to Germany for a restorative stay in the spa town Carlsbad, he booked a Munich hotel that was “a favorite of American tourists.”

Researchers Have Found Two New Pages in Anne Frank's Diary. Should We Read Them?

For emigrants, modes of transportation become agents of destiny, fraught and liberating, acting as bridges between past and present lives. In Sebald’s Austerlitz, the narrator encounters the title character in the waiting room of Antwerp’s Centraal Station. “When he wasn’t busy writing something down, he turned his attention to the rows of windows, the pilasters or other details of the hall’s construction.” (Austerlitz’s mother, we will learn, was deported by train to Theresienstadt.) Austrian, similarly, was fascinated by ships. After arriving in New York, he continued on to Albany on a steamer called the Isaac Newton. “I sat up all night long in the engine room watching the machinery,” he wrote. He expanded his businesses from shops to copper mining and eventually bought his own ships, ferrying passengers and cargo across Lake Superior. (He christened his favorite the Peerless.) Even when his memoirs are at their most perfunctory, they include detailed measurements of steamers, and he felt invigorated by port towns. But a friend of his was killed when a ship called the Sunbeam sank on Lake Superior.

When Austrian returned to Wittelshofen, in 1889, bearing silk shawls and other gifts, the bond between him and his home already seemed severed. “We went around to the old school houses, to the synagogue and the church at which we took a mere peep from the outside,” he wrote. “Even the buildings looked smaller and more dilapidated than I had pictured them.” The grave of Abraham Isaac Oestreicher was crumbling away; the inscription on it was unreadable. By an operatic coincidence, an old friend and neighbor of Austrian’s, Frumeltn, died the evening he returned. “She had gone to a great deal of trouble to get up a grand meal for us. Exerting herself when she was ill had brought on a sudden death.”

Destruction is a constant in Sebald’s novels and in history. Austrian emigrated to America in time for his descendants to avoid the Holocaust, but he knew jagged suffering. He saw Abraham Lincoln’s body during the funeral procession in New York in April 1865, and watched strangers fight over souvenirs. He gave sandwiches and coffee to people made indigent by the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. He watched sheriff’s deputies enforce a mining company’s monopoly with muskets. One son, Austrian’s “little sufferer,” succumbed to scarlet fever at age two. Another died as a teenager, in 1903. “It is ever too fresh in our minds,” Austrian wrote years later. His daughter Alice lost her two-year-old boy.

As Sebald knew, ordinary lives are rich in symbolic drama. We must simply choose to read them as literature.

As Sebald knew, ordinary lives are rich in symbolic drama. We must simply choose to read them as literature. The most moving parts of The Emigrants are when Sebald switches from his own fluid writerly voice to the shorter sentences of his character’s journals. Circumstances pile up, allowing us to choose whether to interpret them as metaphor or coincidence. In an essay from Teju Cole’s Bright and Strange Things, the novelist visited Sebald’s grave. Near the site of the car crash that ended Sebald’s life, Cole noticed a newspaper headline about a murder. “It was another set of lives, another set of fates rising to the surface for a moment before falling into history,” Cole wrote, acknowledging both the transient nature of these moments and their emotional power. There is potential for metaphor in the objects of Austrian’s life, but more importantly, it can be read as one of “small and neglected stories” Sebald treasured.

When I visited Wittelshofen, I was reminded of yet another line of Sebald’s, from Vertigo: “The village was, I thought during my late arrival, more foreign than any other conceivable place.” Austrian must have experienced something similar when he returned to Wittelshofen. If there is no trace of my family in Wittelshofen, that is at least partly by choice. Austrian’s memoirs are a more important document. As I read them, it was like, as Sebald wrote, they “had expanded throughout all possible dimensions of time, as if they had endured into the lines I’m writing now.”