Recommended Reading

Sunset Is the Best Time to Get High

Helen Phillips recommends "Pineapple Crush" by Etgar Keret, translated by Jessica Cohen

INTRODUCTION BY HELEN PHILLIPS

Humor, Etgar Keret recently said to me, is sometimes the only way to maintain one’s dignity.

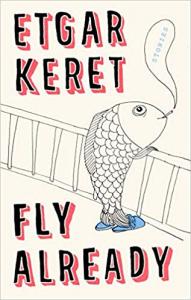

We were discussing his new collection, Fly Already, a book equally hilarious and devastating, punctuated by moments such as one in the story “Fungus” when a person in a tight spot thinks, “it’s too embarrassing to die like this, in shorts and Crocs.”

Fly Already is filled with scenes in which humor is the sole trapdoor available to Keret’s self-defeating anti-heroes. Many of his protagonists are men locked into their problems and pathologies and bad habits, stuck in tragic or difficult or absurd circumstances. But when a person makes a joke, he steps outside the trap of himself; he reveals that his perspective is broader than it first appears.

Fly Already is filled with scenes in which humor is the sole trapdoor available to Keret’s self-defeating anti-heroes. Many of his protagonists are men locked into their problems and pathologies and bad habits, stuck in tragic or difficult or absurd circumstances. But when a person makes a joke, he steps outside the trap of himself; he reveals that his perspective is broader than it first appears.

If humor is one escape hatch, conversation is another. As the narrator of “Car Concentrate” observes: “A conversation is like a tunnel dug under the prison floor that you—patiently and painstakingly—scoop out with a spoon. It has one purpose: to get you away from where you are right now.”

The story published here, “Pineapple Crush” is narrated by a guy whose life lacks forward motion. He gets stoned every evening and dreamily follows strangers around. He begrudgingly works in an after-school program, where he “picks on weak kids” and calls his elementary-school charges names like “poop face.” He tries—and fails—to lie his way out of problems.

And yet Keret’s narrator is not unlikeable. His voice is infused with dark humor, and his wry observations charmed me even as I despaired at his actions. He is very much aware of his multitude of failings, and he offers us many wise and funny articulations about himself and the world around him.

This narrator is capable of real (if fleeting) connection with others. Sharing a joint and a joke with a woman he’s just met, someone overloaded with problems of her own, he feels “happy with her, briefly useful to humanity.” When a second-grader calls him out, asking him why he is so unkind to children, he admits to the reality the reader has already perceived: “Maybe because most of the time I feel weak myself, and when I pick on someone, I feel stronger.”

Throughout Fly Already, the reader experiences a number of car wrecks, some figurative, some literal. But there is a surprising quality of uplift here. Life is hard when you’re mired in yourself. Life gets better when you can—by cracking a joke, by conversing well—transcend yourself.

–Helen Phillips

Author of The Need

Sunset Is the Best Time to Get High

Etgar Keret

Share article

“Pineapple Crush”

by Etgar Keret, translated by Jessica Cohen

The first hit is the one that colors your world. Save it for the evening—and any piece of trash flickering across your TV screen will be riveting. Puff it at midday, before you get on your bike, and the world around you will feel like one big adventure. Smoke it as soon as you wake up in the morning, before your coffee, and it’ll give you the energy to crawl out of bed or dive back in for another few hours of sleep.

The first hit of the day is like a childhood friend, a first love, a commercial for life. But it’s different from life itself, which is something that, if I could have, I would have returned to the store ages ago. In the commercial it’s made-to-order, all inclusive, finger-licking, carefree living. After that first one, more hits will come along to help you soften reality and make the day tolerable, but they won’t feel the same.

I always take my first hit at sundown. The after-school program where I work is half a mile from the beach, and I finish at five, when Raviv’s sweaty mother, who always gets there last, finally comes to pick up her snot-nosed second-grader. That leaves me time to run errands, if I have any, then to grab a coffee on Ben Yehuda or HaYarkon, and mosey over to the promenade. That’s where I eagerly wait for the sun to kiss the sea, the way a kid waits for his good-night kiss, the way a pimply teenager slow-dancing at prom waits for his first French kiss, the way a wrinkly old man waits for a wet peck on the cheek from his grandchild. The second the sun starts reflecting off the water, I pull out the joint from my pack of Noblesse cigarettes and light up.

I smoke that joint quietly. I try to be in the moment, to feel the breeze on my face, to take pleasure in the colors of the sky and the way the sea sizzles in the red sunlight. I try, but I can’t really do it, because as soon as I take the first puff, my mind starts letting in all kinds of thoughts about how it was a mistake to call that first-grader Romi “poop face,” because the little snitch will tell her bitch of a mother about it, and she’ll go straight to the principal. And about how the tall, skinny second-grade teacher is nicer to me than the other teachers are, always smiling and asking how I am, so maybe something could happen there. And also about my rich asshole brother who keeps working over Mom to make her stop helping me out with my rent, like it’s any of his business. I always try to lose those thoughts and not waste the best hit of the day on them, and sometimes I can do it. But even when I can’t, I figure if you’re going to think bad thoughts about your brother, you may as well be high while you’re doing it.

Life is like an ugly low table left in your living room by the previous tenants. Most of the time you notice it and you’re careful, you remember it’s there, but sometimes you forget and then you get the pointy corner right in your shin or your kneecap, and it hurts. And it almost always leaves a scar. When you smoke, it doesn’t make that low table disappear. Nothing except death can make it disappear. But a good puff can file down the corners, round them off a little. And then when you get whacked, it hurts a lot less.

After I finish smoking, I get on my bike and take a little spin around town. I watch people. And if I see someone really interesting—and that someone is almost always a she—I follow her and make up a little story: the person who just got yelled at over the phone by the tanned woman I’m following is her younger sister who’s always making eyes at her husband at Friday-night dinners; the pint of ice cream she picked up at the corner store is for her spoiled brat of a son; and the drugstore stop is for the Pill, so she doesn’t accidentally have another spoiled brat. After that, if the weather’s decent, I plunk myself on a bench on Ben Gurion Boulevard and smoke a regular cigarette, and I sit there as long as the high or some bit of it is still going. When it completely fades, I jump on my bike and head back to my apartment to the TV, to Tinder, computer games, trance music.

For four years, I’ve been taking my first drag at sundown. Barely missed an evening. There were a few anomalous puffs that managed to convince me to light up earlier in the day, but nothing major. And that is something that a suggestible, addictive personality like me can certainly be proud of. More than one thousand puffs on Frishman Beach at sunset. More than one thousand uninterrupted puffs until she came along. With her “Excuse me?” so soft and gentle that even before I turned around I knew she would be ugly, because pretty girls don’t have to try so hard to be gentle: people do whatever they want anyway.

She was older than me, about forty. White blouse, black skirt. Brown hair tied back. Smart eyes. Glistening complexion, a few wrinkles, mainly under the eyes, but they only made her sexier.

I wanted to ask if I could help, but because I was smoking, the only sound that came out was a slightly aggressive “What?” I think it sounded aggressive, because she took a step back and said, “I’m sorry, nothing.” I cleared my throat and said, “No, it’s okay, tell me. What did you want to ask?” She smiled shyly and half whispered: “I wanted to ask if that’s pot.” She didn’t look like someone who stopped people on the street to ask them a thing like that, and she definitely didn’t look like a cop. So I nodded. “Can I have some?” she asked, and held out two fingers. Her hand was shaking.

I handed it to her. She tried to inhale and say thanks at the same time. It ended with a splutter. We both grinned. Giving up on the thanks, she took a long drag and held it in, like someone diving underwater. I hadn’t seen anyone smoke that way for years, like a kid smoking a cigarette. She tried to give the joint back but I signaled for her to keep smoking. After another few puffs she tried to give it back again, and this time I took it. We smoked together. When the joint was done, the sun had already set. “Wow,” she said, “I haven’t smoked for so many years that I forgot how much fun it is.” I wanted to say something clever, but the only response I could come up with was that it was good stuff. She nodded and said thanks. I said she was welcome and she walked away.

That was it. It was supposed to end there. But like I already said, when I’m high I follow people, especially women, and so I followed her. She walked to Ben Yehuda, where she bought a bottle of mango-flavored “Island” juice. From Ben Yehuda she took a cab. I followed the cab and saw her get out at the Akirov Towers, walk into the lobby of one of them, and say hello to the doorman. Forty years old, pressed white blouse, Akirov—not exactly the kind of woman you’d expect to share a spliff with on the beach.

On the way home I told myself I should have hit on her. Asked for her phone number. My greedy brain kept scolding me for not trying to take advantage of the situation, to get something out of it, but then my heart said very clearly that it would have been not cool to do that. She asked me for a drag, that’s what she wanted, and, yes, I could have tried to get somewhere with her, but the fact that sometimes when a woman smiles at me on the street I can just smile back without trying to cash in on it actually says something good about me. Maybe about her, too, considering that’s what she brought out in me.

The day after I get high with Akirov, I finish work early. Raviv’s mom comes to pick him up at four fifteen because they have a doctor’s appointment with a specialist. In the thirty seconds it takes her to put a sweatshirt and backpack on her booger-smeared kid, she manages to say the word “specialist” five times. Except that not one of those five times does she say what he’s a specialist in. Maybe snot.

I hop on my bike and get to the beach earlier than usual. I grab a bench and sit there people watching to pass the time until sunset. There’s not much foot traffic. Tourists in T-shirts and sweatpants, gushing about how nice it is in February in Tel Aviv. Israelis on their cell phones, hurrying somewhere without even noticing that they’re by the sea. When the first ray of sun scratches the waves, I don’t light up yet. And even though I’m super-horny for that first puff, I wait another three or four minutes before I start. I don’t even know why.

While I smoke, I do what I always do: I look at the sea, try to live in the moment, let the beauty sink in. But thoughts fly around my head in all directions. I imagine Raviv at the specialist. Maybe he has something terminal. Poor kid. All the kids at after-school torment him. I do, too. I call him Snotface, and I’ve mimicked him wiping his nose on his sleeve. I promise myself I’m going to stop, and the thoughts go back to her again. Akirov. Some part of me was hoping she’d come again today, but it’s weird enough when someone you don’t know asks to smoke with you, just like that, right on the promenade—what are the chances of it happening two days in a row? I finish smoking and keep sitting there until the sun completely sinks into the sea. It’s not nice of me to call her Akirov. So what if she lives in a luxury building? That’s just stereotyping. Like calling an Arab “Arab,” or a Russian “Russian.” Although, when I think about it, that’s exactly what I always do. I’m getting cold now. It was hot in the afternoon so I didn’t bring a jacket.

I’ve already stood up and taken a step toward my bike when I see her coming. She hasn’t seen me yet. I turn my back to her and start digging through my pockets. I usually roll only one joint ahead of time, but today I have two, because I promised to bring one for Yuri, the Russian security guard who stands at the school gates. He never turned up for his shift, so I still have it in my pack. I pull out the second joint and light it, all casual, like I’m not already high as a kite from the first one. I take two quick drags, still with my back to her, and then I turn around. She’s really close now, maybe twenty steps away, but she hasn’t spotted me yet. She’s on the phone. It’s a grim conversation, I can tell. I’ve had enough of them in my life to recognize one. She hangs up right as she walks past me. It looks like she’s crying. I follow her. Fast. But I don’t run. I don’t want to look too eager. When I’m right next to her I say, “Excuse me?” but in an American accent. Like those old American Jews who always say “Shalom?” and when you stop to see what’s up, they speak to you in English. She looks at me. No recognition. “You dropped this,” I say, and hold out the joint. Now the lightbulb goes on. She smiles and takes it. When she’s right in front of me like that and I can see her eyes, I can tell for sure she’s been crying. “Wow,” she says, “you came just when I needed you. Like an angel.” “What do you mean, like?” I say, “I am an angel. God put me on the promenade today just for you.” She smiles again and blows out a little cloud of smoke: “The angel of weed?” “I’m the angel who makes wishes come true,” I tell her. “Five minutes ago a little girl wanted a Popsicle, and before that it was a blind guy who wanted to see. I can’t help it that I landed a pothead.” I manage to make her laugh. Or rather, the combination of the pot and me manages to make her laugh. She’s happy, Akirov. And I feel happy with her, briefly useful to humanity.

When the joint is finished, she says thanks and asks which direction I’m going in, and I realize that while we were smoking I kept walking with her and got far away from my bike. I consider lying, but then I decide to confess. I tell her my bike is tied up back where we met.

“Do you come here every day?” she asks.

I nod. “And you?”

“I have to.” She shrugs and points south to the corncob skyscraper. “I work there.”

I tell her I always come to the promenade after work, to light up a joint with the sunset. A girl once told me that watching the sunset opens up your heart, and my heart’s been closed for a long time, so I come here every day to try to open it up.

“But today you were late,” Akirov says, glancing at the time on her phone.

“Today I was late,” I concur, “which is a good thing. Otherwise we wouldn’t have met.”

“So if I come here tomorrow at sunset, will you share with me again?”

I pause for a second and scrutinize her. Maybe something’s there, maybe she’s hitting on me. But I can see she isn’t. It’s just the pot. Even today, when I stopped her, she only recognized me by the pot. “Sure. It’s more fun to smoke with someone nice than alone anyway.”

For five days me and Akirov have been smoking at sunset. Five days, and I still know almost nothing about her, not even her name. I know she’s vegetarian but sometimes eats sushi, and that she speaks good English, and French, too, because this pain-in-the-ass French tourist came up to us the day before yesterday and Akirov explained to her in fluent French how to get to the port. I also know she’s married, even though she doesn’t wear a ring, because on one of our first days she told me that her husband doesn’t let her smoke pot because it’s illegal and because it screws up your short-term memory. “And what do you say to that?” I asked. I wanted to see if I could get her to spill any dirt on her husband. “I don’t have a problem with it being illegal,” she said, shrugging. “And the short-term memory thing? To be honest, it’s not like I have such great short-term memories to preserve anyway.” Well, that was almost a complaint. Either way, it was obvious there was something weighing on her. Something she didn’t talk about even when she was stoned, which for me was the sign of a strong person. Strong and not a whiner. That—and the thing that happened with the fascist vice cop yesterday.

It was the first time a cop had ever come up to me while I was smoking, and this guy was an especially creepy one. Short but muscular, with a neck as thick as a utility pole and a tight plaid shirt with cut-off sleeves. He shoved his badge in my face and wondered in a cocky voice if he could ask what I was smoking. Akirov, without missing a beat, pulled the joint out of my mouth, took a drag, blew smoke right into his face and said, “Marlboro Lights.” She tossed the joint over the railing onto the sand below, and just as swiftly pulled out a pack of Marlboro Lights from her pocket, lit one, and held out the pack: “Want one?”

The cop flicked her hand away. “What do you think?” he screamed. “You think I’m retarded?”

“I’d rather not answer that,” she said with a sweet smile, “because I am a law-abiding citizen, and insulting an officer of the public is a crime.”

“ID! Show me your ID right now!”

Akirov pulled out her driver’s license and also handed the cop a business card. “Keep this,” she said, “I’m a lawyer. And, judging by your face, it’s only a matter of time before you beat the crap out of a Palestinian and need legal counsel.”

“I know your firm,” the cop said as he dropped her card on the path. “You guys’ll defend any shithead if he has enough money.”

“True,” said Akirov, jerking her head at the tossed card, “but once in a while we also defend shitheads pro bono.”

The cop didn’t answer. He went over to the railing and peered down at the sand strewn with trash. You could see from the look on his face that he was debating whether or not to jump down and try to find our roach among the dozens that littered the beach. “Don’t give up,” Akirov called out, “if you look carefully you’ll find it in an hour at most. And if you take it to forensics they may even be able to isolate my fingerprints, and then you can go to your commissioner and tell him you want to press charges for a marijuana roach. Which is maybe not quite the same as solving a double homicide, but hey . . .” “Bitch,” the cop muttered without thinking, and Akirov continued, “An officer of the law cursing at a lawyer, on the other hand, is a slightly more serious offense.” She winked at me when she said that. “Okay, get the hell outta here,” the cop snapped. I started moving toward my bike but Akirov grabbed my hand and held me back. “You get the hell out, Popeye,” she told him, “before I decide to ask for your details and report you to Internal Affairs.” The cop gave us a violent glare, and my instincts told me to make myself scarce, but Akirov’s hand around mine told me to stay put. Her clammy palm made me realize she was stressed. That was the only sign. The cop hissed something and walked off, and when he was far enough away, she leaned over and picked up the card. “Dumbass,” she murmured, “we lost half a joint because of him.” With an expert hand she tore off a strip of the card to use as a filter. “You have enough on you for another one?” she asked. I almost said that I didn’t but that I lived nearby and we could go over to my place, but something about her wouldn’t let me lie. So we rolled another one, sitting on a promenade bench. A third of her business card became a filter. The other two thirds, which said “Iris Kaisman, Attorney,” stayed in my pocket.

On Friday evening I’m at my mom’s for dinner. My older brother, Hagai, comes, too, with his daughter, Naomi. You can tell from the second they walk in that they’re half fighting. It’s not hard to fight with my brother. He’s one of those people who are always sure they know everything. He’s been that way since we were born, and the boatloads of money he made in the tech industry have only made things worse. Not even the wallop he got two years ago when Sandy, Naomi’s mother, died of cancer, did anything to soften it. Naomi’s seventeen now, a beautiful, tall girl, like her late mother, and even though she has braces, she doesn’t look or sound like a child for even a second. At dinner she tells us excitedly about a species of dwarf jellyfish that lives forever. This jellyfish matures, mates, then becomes a baby again, and it goes on like that ad infinitum. “It’ll never die!” Naomi gushes, and the mixture of enthusiasm and braces makes her spit on Hagai and me a little bit. “Think about it—if we can study its genetic composition thoroughly, then maybe we’ll be able to live forever, too.”

I grin at her. “To tell you the truth, even sixty or seventy years sounds like too long to me.”

My brother explains that Naomi wants to go to Stanford next year and get her degree in biology.

“Wonderful!” my mom exclaims. “You’ll be brilliant.”

“What do you mean, ‘wonderful’? I told her she can do her army service first, like everyone else, and when she’s done I’ll pay for her to study whatever she wants.”

“Not an option. The army has nothing to offer me,” Naomi says.

“It has nothing to offer you? It’s the army, it’s not a branch of Zara! No one goes there because of the selection or the styles. You think income tax has anything to offer me? No, but I still pay it every month. Isn’t that so?” Hagai glances at me, expecting me to intervene on his behalf. Not because he’s always been such a great brother and I owe him. He hasn’t. But because he’s so right.

“Nothing bad will happen if you skip the army,” I tell Naomi. “The world will be better off with you studying jellyfish than spending two years making coffee for some horny officer.”

“Yeah, take your uncle’s advice,” Hagai hisses, “he’s really gone far in life.”

After dinner, when Hagai and Naomi are gone, my mom gives me another slice of cake and asks if everything’s okay and if I’m seeing anyone. I tell her everything’s fine, that they’re pretty pleased with me at school, and I’m dating a lawyer. I almost never lie to my mom. She’s the only one who has to accept me as I am, so there’s no need, but this lie isn’t for her. It’s for me. It’s for those few minutes when I get to imagine I have a life different from the one I really have. When I warm up at night in bed with someone who isn’t “divorced, looking for a noncommitted relationship” whom I dug up on a dating app. At the door my mom says, “You know Hagai didn’t mean it,” and when she hugs me she puts some bills in my jeans pocket. Whenever Hagai lays into me, she gives me a few hundred shekels. It’s starting to feel like my side job.

I take a cab to the bodega next to my apartment and buy a cheap bottle of whiskey, which the Ethiopian checkout guy with the dyed-blond hair swears came from Scotland even though the label is in Russian. At home I finish off half the bottle. Then a slender forty-six-year-old from Tinder comes over. Before we fuck she tells me it’s important to her that she be honest and inform me that she has cancer and it might be terminal. Then she takes a deep breath and says, “That’s it. I’ve said it. If you’re not comfortable, we don’t have to do it.” “I’m totally comfortable,” I say, and when she comes she screams so loud that the upstairs neighbor bangs on my door. Afterward we smoke a cigarette together, a regular one, and she takes a cab home.

Sundays are usually my least favorite day of the week. It wasn’t always this way, only since I started working. Before the after-school program I did nothing for five years, and then I hated all days equally. Honestly, most of the time I couldn’t really tell the difference. When I got up at midday, I would look at my watch and wonder if I had any hash or weed or money left and if I remembered where I’d put my cell phone and keys. Questions like “what day is today” hardly ever came up, and other than Fridays, when I went to see my mom, the whole rest of the week felt like one big, sticky glob of sleep-wake-eat-shit-TV and the occasional fuck.

My job set things straight. It separated the days out. Mondays started to mean darbouka class and the pretty counselor with the tongue piercing, and Wednesdays meant meatballs in sweet tomato sauce in the cafeteria, which the kids hated but always reminded me of Grandma Geula’s cooking. And Thursdays were soccer in the yard and the kids looking at me like I was Cristiano Ronaldo and not just a tired grown-up who could barely outsmart a bunch of seven-year-olds. And then shitty Sundays with the quasi-Nazi roll call put on by Maor, the guy who runs the after-school program, who always had a bad word for each of the counselors before he disappeared from our lives for another week. After my chill Saturdays, that always rubbed me the wrong way.

But this week, for the first time since I started work, I was looking forward to Sunday. To the sunset, to the promenade, to getting high with Akirov. And it wasn’t out of horniness or anxiety about how maybe I’d say something and she’d come over to my place. It was that I genuinely missed her. I missed someone I didn’t even really know. And that was exciting and at the same time humiliating. Because that feeling of missing someone was mostly evidence of how vapid my life had become.

Except Akirov didn’t come on Sunday. I waited for her till it got dark—long after, in fact. She didn’t come on Monday or Tuesday, either. While I smoked alone, I reminded myself that she was just a random woman who’d shared a joint with me on the promenade a few times, not my fiancée or someone I’d donated a kidney to or anything. But it didn’t do any good.

On Wednesday, after the kids finish wrangling their lukewarm meatballs, I realize Raviv isn’t there. I never count them, even though Maor says we’re supposed to count them every hour. But when someone’s missing, I usually figure it out, so I ask Yuri, who says he saw a few kids go behind the gym. They’re not allowed to leave the classroom without permission, and by the time I get to the gym I’ve had time to think up the punishment I’ll give Raviv, feel sorry for him, and cancel it. Behind the gym, in the long-jump sand pit, I see Raviv crying, and not far away from him I see Liam, the meanest kid in my group, lying facedown in the sand while some fat redhead whose face I’ve seen before sits on top of him and punches him in the back. He’s punching the way a kid does: lots of anger, very little technique. Without even knowing how things got to this point, I’m with the redhead. I’ve felt like punching Liam myself a bunch of times. The kid doesn’t talk, he just gives orders, and even that he does in a shitty way. Every other line out of his mouth is about how he’s going to tell Mom, or the teacher, or the principal.

The redhead keeps pounding on Liam, and I know I should run over and separate them. The fact that they disappeared from the classroom is my screwup, and now I’m really going to get in trouble, especially with Liam’s mom being on the parent council. But as I watch the redhead railing on him, a little voice inside me tells me to wait a while longer, just till he lands one really good punch.

This has not been a good week. Not good at all. All that embarrassing waiting around for Akirov. I didn’t even try to bring a single girl home. This fight is without a doubt the highlight of my tedious week, and another few seconds of enjoyment aren’t going to hurt anyone. While I think all this, the redhead gets off Liam’s back, and just when I think the whole thing has played itself out, he takes a step back and slams his foot on Liam’s head. As I start running, I realize Raviv is on to me. He saw me watching the fight that whole time without doing anything. I sprint the few feet between me and the redhead as fast as I can, both because I’m stressed and to confuse Raviv a little, so he’ll think afterward that he must have been wrong: it wasn’t possible that I was standing there watching instead of breaking them up and that I took off so fast.

When I get to the redhead I shove him hard enough to move him off Liam and I yell, “What are you doing? Are you out of your mind?” Then I bend over to check on Liam, and all that time out of the corner of my eye I can see Raviv watching me. Liam’s upper lip is bleeding and he looks unconscious. The redhead stands there wailing. He says Liam cheated him on Trashies and when he asked him to give back his cards, Liam told him he had poop-colored eyes and his dad was unemployed. From the way the redhead says it, I can tell he doesn’t even know what “unemployed” means. I try to talk to Liam and shake him gently, but he doesn’t respond, and I get really nervous. I tell the panicky redhead not to move and I run to the water fountain. On my way back I can hear Liam up and screaming, “You’re finished at this school, you fat-face loser! My mom’ll make sure of that!” Liam is sitting on the ground with his hands on his face, and the redhead stands next to him, shaking all over, really sobbing now. Suddenly Yuri turns up. I’d left the kids alone in the classroom and one of them found a lighter in my bag and set fire to a poster of Yitzhak Rabin in the hallway. Yuri’s account of how he put out the smoldering poster makes it sound like, at the very least, he’d saved a baby from a burning house. I splash water on Liam’s face. He looks all right now and his lip is hardly bleeding anymore. The redhead keeps blubbering, but I’m not interested in him. What I am interested in is that snot-faced Raviv, who doesn’t take his eyes off me even after we go back into the classroom. I call Liam’s dad, who works as a land surveyor and is usually at home, and he gets there in five minutes. Liam screams that he took too long and he’s going to tell on him to Mom, and then he tells him about the redhead. He embellishes a lot, and says the redhead hit him on the head with a rock, but I don’t intervene. As long as he doesn’t start in on me, I figure I’m better off keeping quiet. Then the mom of the twins with the unibrows arrives. She has a South American accent. She had the twins through IVF and, judging by the way they turned out, she must have used a caveman’s sperm.

Eventually it’s just me and Raviv. I let him play on my iPhone, even though I never do that, and while he annihilates entire species on a game I downloaded a few days ago, I try to talk to him about what happened. “It’s not okay that you and Liam ran away from class without permission,” I tell him, but I say it pretty gently, like a kind mother, so he’ll know I’m not against him but at the same time he’ll understand I have something on him. “I won’t tell your mom,” I continue, “but I want you to promise not to do that again.”

And this kid, without even looking up from the phone, says, “I saw you.”

“Saw me what?” I ask, like I have no clue what he’s talking about.

“I saw you while Gavri was beating up Liam. You were smiling.”

“No I wasn’t. I wasn’t smiling. I ran. I ran as fast as I could to break it up.”

But Raviv isn’t with me anymore, he’s in the game. Shooting lasers at anything that moves.

When his mom gets there, I don’t call her out for being late like I usually do. I just tell her, “You have a really good kid. He’s a sweetheart.” Right next to him, so he can hear.

In the five minutes it takes me to get to the promenade, I have two unanswered calls and a text message from Maor. The message is blank. The fucker was too lazy to write anything, but he wanted me to see it and call him back. I debate whether to have a smoke first and then call him, or the other way around. The pro of smoking first is that the reefer will soften the discussion, envelop the whole unpleasantness in styrofoam and bubble wrap. The con is that I’ll need to be sharp with him. I’ll have to answer fast, maybe make up a lie or two right on the spot. I go with the second option and call him cold sober.

Maor yells at me: Liam’s mother called and vowed to get all the other parents on board and make sure he loses the program next year. She’s been compiling a list of complaints on him all year and she’s going to make everything public, including the fact that the lunches are sometimes served frozen. Maor says that if she pulls it off, this whole episode could cost him two hundred thousand shekels and it’s all my fault. Her kid won’t be at school tomorrow because he has a concussion, and Maor wants me to go visit him before work and take him some candy or a toy, and suck up to his mom so she’ll get off his case. The whole phone call is a total drag. He repeats everything ten times. I wish I’d smoked first. Before he hangs up he threatens me again. He says if they take away his license, he’ll sue me. I tell him to calm down and I promise to go over tomorrow and kiss the mom’s ass. By the time the call is done I’ve missed the sunset. I sit there in the dark, staring out at the sea, fully sober. Once the sun has set, there’s nothing in that spot apart from ugly tourists and lousy music from the restaurants on the beach. And the next day I have to set my alarm clock and get up early so I’ll have time to buy a gift for my least-favorite kid in the world. This week started off lousy and it’s only gone downhill.

“I thought you left after sunset.” I hear her voice and I feel—or at least imagine—her breath on the back of my neck.

“Sunrise, sunset—I’ve been waiting for you since Sunday,” I reply with a smile, and then I get mad at myself because instead of saying something positive I managed to sound like a whiner and a doormat all at once.

“Sorry.” Akirov sits down next to me. “Work was a shit show this week. Not just work—life, too.”

I want to ask her what happened but I can sense she doesn’t want to talk about it. So instead of drilling on about it, I take out a joint. After one puff I pass it to her and she sucks it up like a junkie. “I’ve been thinking about this drag for five days,” she says, smiling, and hands it back to me. I don’t take it. “You smoke it,” I tell her, “smoke it to death.” She hesitates for a second and then takes another toke. “Tough week?” I ask. She nods and sniffles. I’m not sure if she has a cold or if she’s trying not to cry. “My week wasn’t so hot, either,” I say. “It’s bad for us to not see each other for so long. It throws a wrench in our karma.”

She smiles. “Listen, I want to ask you for a favor . . .” She digs through her bag while she talks, and I try to guess what she could possibly want from me. “I want to hire you.” She takes out her wallet.

“As what?” I give her a big grin. “Your bodyguard? Babysitter for your kid? Personal chef?”

“I don’t have a kid,” she says with a sigh, “I’m not into food, and I’m pretty good at taking care of myself. I want to hire you to keep doing exactly what you do: come here every day at sunset, and wait for me if I’m late. Not long. An hour at most. And then smoke with me.” While she talks, she counts out the money. “Here.” She hands me a stack of hundreds. “There’s two thousand here. Two thousand for three weeks. What do you say?”

“What do I say?” I repeat her question to buy time. “I say that I come here every sunset anyway, and smoking with you is more fun than smoking alone, so it’s great that you want to pay me for spending a pleasant fifteen minutes with you on the beach when you have time, but taking money for talking to a friend . . .”

“But that’s just it—we’re not friends. And three weeks from now I’m going to vanish from this place and you’ll never see me again. These three weeks are going to be the toughest ones of my life. The daily joint with you will help make them a little bit easier.” Her hand with the money is still held out. When she says we’re not friends, it hurts. It hurts because it’s true. I try to ignore it and focus only on the pragmatic stuff.

“If you want, I can buy you some weed for a couple of hundred shekels. At the rate you smoke, it’ll last you more than three weeks.”

“But I don’t want you to buy it for me. I want you to smoke it with me. I can’t keep weed around. I promised my husband I’d stop buying it.”

“You promised him you wouldn’t smoke,” I correct her.

“I know,” she says, and suddenly she starts crying, “But it’s different with you. Even if he finds out, it’ll be like I just met you on the street and you happened to be smoking so I had a drag, too. It’s not the same as buying . . .”

I take the money. I don’t want her to cry. “Okay, boss, we have a deal.” I give her a wink. “But the two grand only covers drugs. Sex and rock ’n’ roll are extra.”

She laughs, and the laughter and tears come out together. I don’t know what she’s going through, but it sounds like some serious drama, and even though there’s nothing going on between us, I really want to help her. “I only have one condition,” I add as I shove the money into my wallet, “I want you to tell me why you’re disappearing in three weeks. When you said that, the way you said it, it didn’t sound like a good kind of disappearance. And, speaking as . . . your employee, I have a right to know.”

“I’ll tell you,” she says, and wipes her face with her hand. “I promise. But not today.”

The alarm clock on my phone wakes me at eleven. I brush my teeth, shave, and roll a joint for the evening. I do everything fast. I still have to pick up something for Liam and go by his house, and I only have an hour and a half. It’s a good thing he lives near the school.

His mother opens the door wearing a pink tracksuit and a sour face. “I came to check on Liam,” I say, trying to sound like I care.

“It’s a pity you didn’t check on him yesterday, before he was brutally beaten,” she retorts in her low, sludgy voice. “I still don’t understand how a child can disappear from the classroom for almost an hour without anyone noticing.”

My instinct is to say something about how it’s easier to look after kids who respect other people than ones who keep lying and running away, but I remember my talk with Maor, so instead I explain apologetically that yesterday a child brought a lighter to school and tried to burn some posters in the hallway, and since I was busy taking care of this unusual incident, it took me a while to realize that Liam was gone. “I just want you to know, Mrs. Rosner, that I didn’t sleep all night because of what happened. It was a terrible mistake and I want to apologize to you.”

“I’m not the one you should apologize to,” she says in a voice that sounds slightly less furious. “I’m not the one who was beaten unconscious and is still suffering from aches all over my body. You should apologize to Liam.” She takes me to the little shit, who’s sitting up in his parents’ bed, watching a Japanese anime series—a soccer match between robots and aliens. Other than a slightly puffy lip, he looks totally fine. “Liam,” his mother says in a teacherly tone, “you have a visitor.”

“Not now,” Liam says without taking his eyes off the screen, “I’m in the middle.”

“He brought you a present,” she says, trying to tempt him. “Lego Space!”

“I hate Lego.”

“Hey, Liam,” I jump in, “I came to see how you’re feeling.”

“I’m in the middle,” he says, still not moving his eyes off the screen. “Did you get a gift receipt for the Lego?”

At the door, Liam’s mother thanks me for visiting and says she has a meeting with the principal and Maor tomorrow and that she’s not planning to let this slide. “Liam has three older brothers,” she says in a pathos-filled tone, “and as a parent, I have never come across such an extreme incident: a seven-year-old boy attacked with rocks and sticks without anyone intervening.”

I realize the last thing I should do is get into an argument with her, so I just nod. I tell her that if I were a parent I would react exactly the same way. “You have a lovely boy, Mrs. Rosner, and, thank God, he came through this whole thing without serious harm. That’s what really matters.” Walking down the steps, I text Maor to say I made the visit and the mom is still pissed, but I’m confident she’ll calm down before the meeting. He doesn’t answer, which is a good sign. When Maor texts or calls, it’s always bad.

The afternoon at work goes by without incident, but it’s tense. All the parents who come to pick up their kids throw out something: they’re worried, this is not okay. They’re not blaming me personally, but they’re unhappy with the program and the school. The twins’ mother says that in Buenos Aires they’d have at least two counselors for this number of children. Noya’s father, who is an officer in the navy and always wears his uniform when he comes to pick her up, says it all starts with education at home. I murmur agreement with everything they say, and try to look contrite. There’s obviously going to be loads of yelling and threats at the meeting tomorrow, but if I know this school, nothing serious will come of it. They’ll suspend the redhead for a few days, they may even expel him if his parents are weak or suckers, but it looks like I’ll survive—as long as Raviv doesn’t talk.

Raviv and I are the last ones there, as usual. I tell him I downloaded an upgrade for the game he likes and ask if he wants to play. He smiles and holds out his hand for my phone. Before I give it to him, I explain that it’s fine with me for him to play, but it has to be a secret, because if he tells the other kids they’ll want to play, too, and I can’t let everyone do it. Raviv thinks for a moment and then nods. I give him the iPhone and he starts the game. While he plays, I ask him if he’s good at keeping secrets. He doesn’t answer. I don’t know if it’s because of the question or because he’s absorbed in the game. After a few seconds the iPhone makes a happy tune—he must have leveled up.

“Way to go! You’re really good at this!” I exclaim.

“Why did you smile while Liam was getting beaten up?” He doesn’t even look up from the screen when he asks me that.

Now it’s my turn to keep quiet. My instinct tells me to make something up. My instinct always tells me to make something up. But just like with Akirov, I ignore it. “I did it because I don’t like him,” I finally say. “Lots of times he’s done bad things that I thought he should be punished for and he always gets away with it, and when I saw Gavri hitting him—I know this isn’t a nice thing to say, but I was glad.”

Raviv looks up and stares at me. The game keeps running and I hear him getting eliminated, but he doesn’t seem to care. “What did he do? What things did he do that you thought he should be punished for?”

“Lots of things. But mostly it bothers me that he picks on the weak kids.”

Raviv wipes his nose with the back of his hand without taking his eyes off me. “But he’s not the only one who picks on weak kids.” He doesn’t say it, but we both know he means me.

“That’s true, and it’s a horrible thing to do.”

“Then why do you do it?” He doesn’t look angry at all, just curious.

I shrug my shoulders. “I don’t know. Maybe because most of the time I feel weak myself, and when I pick on someone, I feel stronger.”

Raviv nods. He seems to understand me.

It’s cold on the promenade that evening, and there’s a gusty wind. The sky is completely black and it looks like it’s about to storm. I huddle in my coat and wait for Akirov. It’s my first day as her employee. She’s late, but not by very much. She’s wearing a wool hat. I don’t usually like girls with hats—it always makes them look like a character on a kids’ show. But on her the hat sits really well. It brings out the green in her eyes.

It’s too windy to light up, so I suggest we find a lobby somewhere. While we smoke together in the doorway of a decrepit building on HaYarkon Street, it starts raining, and I think about my bike getting wet on the promenade. “What a crappy day,” I say, and she nods, as though something that belongs to her is also getting wet out there. I tell her about my day, and the whole story with Liam and his mother. She asks if I like my job. I think for a moment—no one’s ever asked me that. “I don’t know if I’d use the word ‘like,’” I finally answer, “but I definitely prefer it to working with adults. With kids, you can take a bite out of their sandwich or you can tickle them. With adults it’s more complicated.”

She takes a sandwich wrapped in paper out of her bag. “Want some? I made it this morning. It’s tuna fish.”

I tell her I’m not hungry and ask if I can tickle her instead.

She smiles. “Do you think you’ll get fired?” She takes a bite out of her sandwich.

“I don’t know. I’ll find out after the meeting with Maor tomorrow.”

“I have a tough time with kids. It’s not that I don’t like them, I just don’t know how to get along with them. Oded hasn’t stopped talking about kids since the day we met, and I just keep trying to buy time.”

I ask if Oded is her husband, and I point out that she’s always referred to him only as “my husband.”

“I guess now I feel a little less sure that he’s my husband.”

“What do you mean?” I ask her.

All she says is, “It’s complicated.” Then she asks, “Do you think it’ll keep raining for a long time?” I remind her that she promised to tell me why she was going to disappear, and she nods and says she’ll keep her promise but not today. “I hope tomorrow goes well. I hope you don’t get fired,” she says, and a second before she steps out into the rain she gives me a kiss on the cheek and wishes me a good weekend.

I keep standing in the doorway for a few minutes, thinking about Raviv, about the meeting tomorrow, about Akirov’s husband, Oded, who is now a little less her husband, and about that kiss she gave me. It was a friendly sort of kiss, and it smelled like tuna fish. The rain is coming down harder, and when I get sick of waiting, I walk out into it.

I don’t wake up till four the next day. On days when I don’t have to be at work, I don’t set my alarm clock. On my phone I see a text message from Mom saying it’ll just be the two of us for dinner because my brother is going away for the weekend with a woman he got set up with at work. She puts three exclamation points at the end of the message, like a sixteen-year-old girl. She’s always dreaming about the day when my brother will remarry. Somehow she’s managed to convince herself that all the pissed-off bitterness that Hagai keeps vomiting on us comes from loneliness, and that the minute he finds someone who’s willing to put up with him, he’ll turn into a prince. The good news from my perspective is that I won’t have to see him this evening. Then there’s another blank message from Maor. I try to call him but his phone is off, so I leave a voice mail.

My mom makes an even more awesome dinner than usual— four courses, and for dessert, a layer cake from a recipe she found online. She’s happy because of Hagai, and her happiness is contagious. I drink a lot of wine and we talk about my dad, about missing him, but it’s still a cheerful sort of conversation. My mom says she’d always hoped to live to see grandchildren, and that even though she’s already been a grandmother for ages, her dream is for me to have a child. She asks how my lawyer girlfriend is, and I say everything’s going great, and that Iris actually likes kids, but she’s a little anxious that she won’t know how to manage them, just like I am. “I’m in no hurry,” Mom says with a smile, “I’ve been waiting for you for so long, I can wait a little longer.”

It rains all day on Saturday. I huddle under the covers, watching horror flicks and chain-smoking what’s left of the crappy pot Avri sold me a month ago. Maor’s cell phone is still off but he calls in the evening. He says the meeting didn’t go well. “You told Rosner that a kid brought a lighter to school and caused problems, and that was why you didn’t notice Liam was gone—why did you do that? She brought it up it at the meeting, and the principal talked to Yuri and started poking around. The kid said the lighter was yours, and Yuri told the principal he was the one who put out the fire. So, bottom line, now you’re a liar.” He pauses, waiting for me to say something in my defense. But I have nothing to say and I can’t be bothered anyway. “Rosner and the principal are both pissed off, and it turns out that Gavri, the redhead kid who was punching Liam, his grandfather’s something senior in the Ministry of Education, so they can’t kick him out of school. Rosner was raring to go, she wants blood. So, long story short, I told them you’re done. Don’t show up at work tomorrow. Call me in early March and I’ll leave you a check at the school office with however much I owe you for February. And, dude, next time you lie? Use your brains. So long.” Maor hangs up on me, and I feel pretty fine about that. I didn’t have anything smart to say on the occasion of my termination: it’s not like it was some toast where you have to make a speech and then they give you a watch. Tomorrow I’ll go look for another job. Maybe bartending. Night hours are better for me, and free liquor is just as good as meatballs in tomato sauce. It’s insulting to be fired, there’s no getting around that. To hear someone tell you you’re not good enough is never a good feeling. But doing that work for 2,800 shekels a month wasn’t something I could keep up for much longer anyway. I wonder if any of the kids will miss me when I don’t turn up on Sunday.

At three a.m., Avri texts me: “Awake?” Like I’m his fuck buddy or something. On the phone he tells me his friend just arrived from Amsterdam with some good stuff. “Primo fresh,” he says excitably, “he just shat it out. Should I run you over some?” By four he’s at my place, and I use what’s left from Akirov’s two grand to buy eight grams. Avri tells me it’s called Pineapple Crush, because this stuff is so strong that if you smoke enough of it, you can fall in love with a pineapple. After his passionate speech we smoke a bowl, and I don’t fall in love with anything, but I do fly far, far away in my mind: I think about Raviv, and about that little stinker Liam, and about Liam’s mom in her pink sweats who probably didn’t give birth to him but just shat him out like Avri’s friend shat out the Pineapple Crush for us. Then I think about Raviv some more, growing old and then becoming a baby again like that dwarf jellyfish; but mostly I think about Akirov and Oded, her slightly-less-so husband, and about how she’s pretty much the only ray of light in my life, and now that’s going to disappear, too. I’m so baked that I don’t even notice Avri leaving, and sometime after the garbage truck finishes its round on my block, I fall asleep.

I get up just in time to shower, roll a joint, and bike to the promenade. The rain and wind have stopped, and there’s finally going to be a real sunset. Akirov’s already waiting on our bench. She finished work early. The first thing she does is ask about Maor and the meeting on Friday, and I tell her I got fired, and that maybe it’s better that way. “Now you’re my only employer,” I say, as I pull a joint out of my Noblesse pack, “and that’s why I’ve decided to take this business a little more seriously from now on. Check out the sunset I arranged for you!” It really is a beautiful one, and Akirov sits there silently, probably trying to come up with something comforting to say. I tell her that not only is there a premium sunset today, but premium pot, too. I tell her about Avri and the Pineapple Crush, but I skip the shitting part. The truth is, I’ve been smoking pot for twenty years and I’ve never had anything this good. After a few tokes you’re absolutely flying.

We stay on the bench well after the sun has gone down, and I remind her again that she promised to tell me why she was disappearing. She looks at me with her clever green eyes. She’s stoned out of her mind but she’s still scrutinizing me. She smiles sadly and says she’s also leaving her job, and that it’s ending badly for her, too. Her law firm represents a few organized crime families, and with one of them, it wasn’t just legal advice—the firm was helping them launder money. We’re talking tens of millions, and lots of important people are involved. But she wasn’t. She found out by accident, and like an idiot she went to the police. When she did that, she didn’t realize the extent of it. She thought she’d discovered a onetime transaction, which only one of the partners was involved in. By the time they figured out how serious it was, she couldn’t back out. Now she’s a state witness. She goes to work every day like everything’s normal, eavesdrops and gathers material, and soon, when the whole thing blows up, she’ll be out of here— they’ll put her in the witness-protection program and give her a new identity overseas. Even she doesn’t know where. “Oded told me yesterday,” she said, attempting to sound calm, “that he’s not coming with me. He’s very close to his family and he’s not up for disappearing.”

“I’ll come with you,” I say, and I suddenly take her hand. “I’ll come with you, wherever it is. I love surprises.”

“This shit really is powerful,” she says, laughing.

“Yeah, but regardless, I’d be happy to come. You’re my only employer here, and when you leave, that’ll be over, too. A new place? A new beginning? I could really get behind that. Just imagine if they put us on a tropical island! Every morning I’ll climb up a tree and crack open a coconut for you.”

“You’re really into this!” She laughs some more. “It’s too bad we can’t switch.”

“I don’t want to switch.” I start getting a little choked up now. “I want you.”

She bites her lower lip and nods. Except it’s not an “I know” nod, but more of an “I want you too” nod. And then comes this long second that the world has cleared away for us so we can kiss. But I’m too worked up to just kiss her. My stoned brain is too busy imagining us together, with different names, in a different place.

The second is over faster than I thought it would be. She stands up and smiles awkwardly and says she came to say goodbye because the timeline has changed: they’re picking her up at ten tonight, and she has to say good-bye to her husband and her sister, who doesn’t know anything about all this. I stand up, too, still trying to comprehend how I could have let that second evaporate, and she gives me one of those ordinary American-type hugs and says I’m a special person, which is something almost all the girls who wouldn’t sleep with me said.

“Don’t tell anyone, okay?” she says while she hails a cab. “Even after it all comes out. Promise? That’ll only get me in trouble. And you.”

I nod quickly and a minute later she’s gone.

I bike home, still wicked high, and all the stoplights and the headlights and the cars honking mingle together in my head and it feels like a huge dance floor. The whole city looks happy—too happy. The munchies set in and I stop at the Yemeni falafel guy’s stand on Nordau. Tomorrow Akirov starts her new life in a faraway place, without a husband and with a different name. It sounds like the beginning—or maybe the end—of a fairy tale. I believe she’ll be happy there, wherever it may be, even if it’s without me. Someone else will pick coconuts for her. Or she’ll pick them herself. Wherever they send her, I hope it’s somewhere warm. Every time I passed her a joint and our hands touched, her fingers always felt cold.