Books & Culture

Sweet Lamb of Heaven Is One Part Novel of Ideas, One Part Psychological Thriller

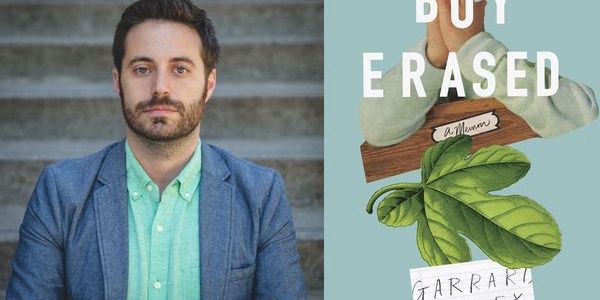

Lydia Millet deserves some sort of award for her books titles alone. Entries include Oh Pure and Radiant Heart; Love in Infant Monkeys; George Bush, Dark Prince of Love; How the Dead Dream; Ghost Lights; Magnificence; and Mermaids in Paradise. Sweet Lamb of Heaven is Millet’s 14th novel, her sixth in the last five years. She deserves another award for this heroic output.

The new novel has much in common with her other recent books: piercingly elegant sentences, a wide range of styles (“My books can’t be one thing all the way along,” Millet has said. “They always twist and turn, tonally.”), a love of the natural world and disgust with what humans have done to it. The threat of extinction in particular hangs above much of Millet’s work. In Sweet Lamb of Heaven, it shadows a young mother as she faces another threat, similarly malign, but more personal and immediate — the threat of a man against a woman.

The book initially resembles a diary whose canny author, Anna, tells us that she used to hear voices. Now she’s hiding out in a coastal Maine motel with her effulgent little daughter in tow and an ice-hearted husband in pursuit. Anna and this sociopathic man, Ned, used to live together in Alaska, but they’ve been estranged for six years. For a while, Ned hadn’t cared that Anna had taken their kid and left, but now he wants “his girls” back in Anchorage so they can serve as stage props for his burgeoning career as a politician, a Family Research Council-type. As Ned begins to take increasingly menacing (and eventually violent) measures to get what he wants, Anna’s sanity begins to unwind, and the narrative accelerates. Sweet Lamb of Heaven twists and turns into a thriller.

And like any proper thriller, the book piles questions onto the reader. How far will Ned go? What’s with all the other guests at the motel? But the novel’s central mystery is the source of the voice that Anna had been hearing. Anna tells us that she didn’t have any other symptoms of mental illness, and she says the voice doesn’t bear the hallmarks of a hallucination. It did seem tied to her daughter, Lena; Anna first heard the voice when Lena was born and it went quiet once she learned to talk. Anna writes,

The voice made light of what it held to be false ideas — for example, the yearning for an all-powerful father who grants wishes and absolves. On that subject it seemed to evince something like condescension, rattling off mocking wordplay when we passed a church marquee or once, another time, when I stood at the front door trying to get rid of a Witness.

Without offering any pat explanation for the voice, Millet uses it as a vehicle for ideas about God, nature, and language. It’s a brilliantly simple conceit that carries an incredible amount of symbolic weight.

Millet sets Ned up as a kind of antithesis to the voice. He is the cold rationality to its nonsense, the physical magnificence to its ephemerality, the mortal evil to its divine rightness. And his noxious right-wing politics seem particularly appropriate to contemporary American politics — it’s no stretch to read Ned’s dialogue in Ted Cruz’s voice — and the concerns that animate Sweet Lamb of Heaven are in direct conflict with the narrow worldview promulgated by Ned and Ted.

But Millet’s ideas can be more interesting than her characters. Anna’s mind is agile enough to make her a good mediating intelligence, but everyone else might have been culled from central casting. Lena’s precocious and adorable; the motel manager is avuncular and a little mysterious; the local librarian, who serves as a romantic interest, is virtuous and noble, if a tad overbearing. Anna describes her husband compellingly: He’s attractive and charismatic “Both before and after we were married, men and women alike would confide in me about their attraction to Ned,” but also cruel, manipulative, and sinister. “Ned’s monotony of empty assertions in the service of self-promotion, self-replication and mastery for its own sake, his reach that extended past the boundaries of even the body — that was a weapon without end.” He’s not merely sociopathic, but Satanic, reaching past the boundaries of even the body. But when Ned appears in any way, when he says or does anything, his menace starts to deflate. When he’s trying to be ingratiating. he says inane things like, “You like that Mexican Co-cola, don’t you? Cane sugar, not corn syrup? We need to bring that old-style Coke back to the U. S. of A.” When he’s mad, he snarls and calls Anna, “Bitch.” Ned’s a serious threat — at one point he breaks Anna’s nose — but there’s a gap between how he’s described and depicted.

In the end, the flatness of the characters isn’t too troubling of a flaw. In fact, it’s pretty typical for novels of ideas. You read Millet for the evocative power of her sentences and the moral force of her thought, not for her Strong Male Antagonists. Millet’s an interesting writer with bold ideas, and her plot only gets more engaging with each page, and these qualities make Sweet Lamb of Heaven a worthy entry in an excellent, rapidly growing body of work, evidence that Millet’s in the midst of a significant creative outburst.

Click here to read an interview with Lydia Millet about Sweet Lamb of Heaven and the future of the literary thriller. Click here to read one of Lydia Millet’s story, “Girl and Giraffe,” as part of Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading.