Lit Mags

The 200 Episode Club

Featuring J.Robert Lennon, Rob McCleary, Morgan Parker, and Téa Obreht

AN INTRODUCTION BY HALIMAH MARCUS

Table of Contents

“And So, We Commence” by J. Robert Lennon

“Captain Stubing Has Collapsed” by Rob McCleary

“Magical Negro #607: Gladys Knight on the 200th Episode of The Jeffersons” by Morgan Parker

“Retrieval” by Téa Obreht

Part of the mission of Electric Literature, the non-profit publisher of Recommended Reading, is to preserve the place of literature in popular culture. Sometimes the relationship between the two is clear — film and TV adaptations of books being the most obvious — but at Electric Literature we believe in literature as a pillar of popular culture in its own right.

So what might we expect from literature in popular culture? Through it we can find common ground, enjoyment, and topics of conversation. But making literature popular certainly doesn’t mean dumbing down content; it means trusting in the intellectual and emotional appetites of our audience. It also means having a bit of fun.

The connection between the 200th issue of Recommended Reading and popular sitcoms was initially tenuous and probably still is. While 100 episodes mean a sitcom is viable for syndication, reaching 200 episodes is a mark of longevity few sitcoms ever achieve. (Seinfeld only made it to 180.) Sitcoms in the 200 Episode Club have indelibly made their mark, for better or for worse, on American identity.

Over the next four days, we present four authors writing on the 200th episode of four sitcoms: J. Robert Lennon on The Cosby Show, Rob McCleary on The Love Boat, Morgan Parker on The Jeffersons, and Téa Obreht on Frasier. Each piece is accompanied by an original illustration by poet and artist Chelsea Martin. Because of the talent of these writers, what began as a tongue-in-cheek way to commemorate the 200th issue of this magazine has emerged as a powerful commentary on the relationship between literature and pop culture.

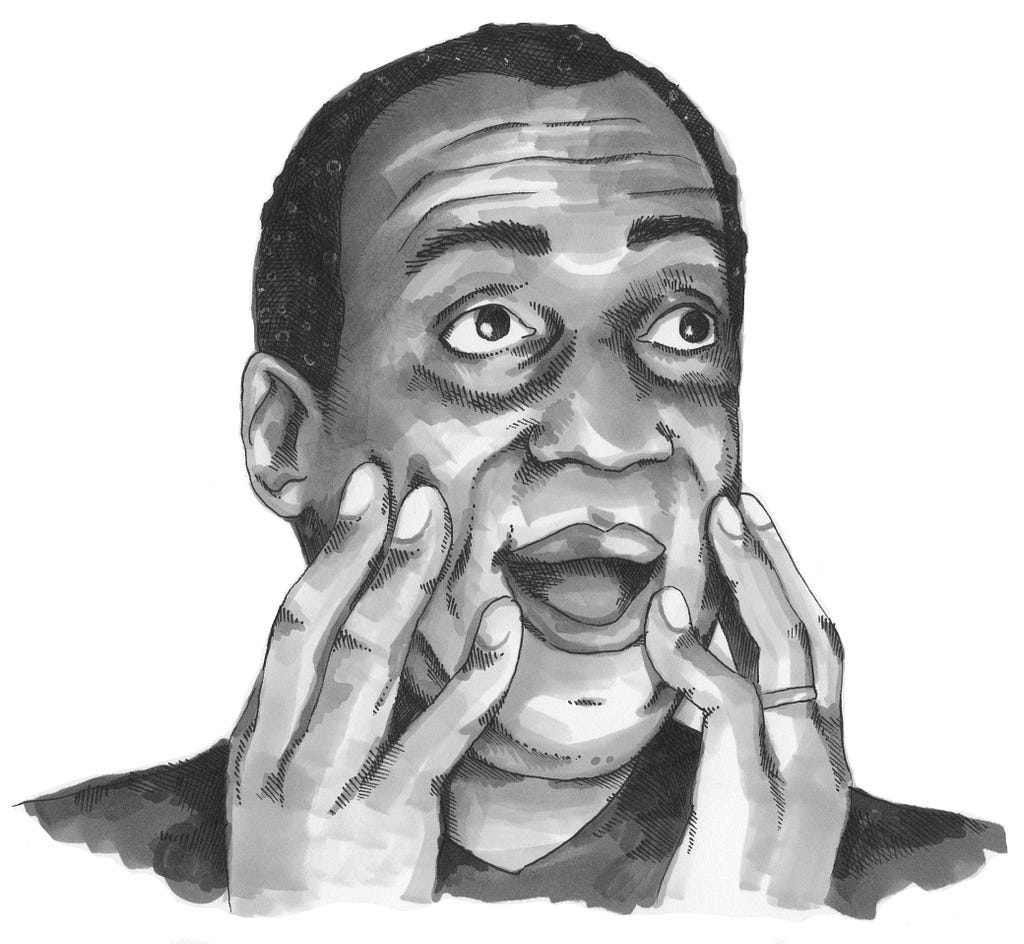

I’ll admit I thought J. Robert Lennon had lost his mind when he said would write about The Cosby Show, given that Bill Cosby has been revealed as a serial rapist and an abuser of power, a man who took horrible advantage of dozens of women with the help of a system that excused, accommodated, and enabled him.

When Cosby’s victims began to speak out, many observers who had grown up watching The Cosby Show knew that if they were ever to watch the show again, it would be with the corrupting hindsight of innocence betrayed. In “And So, We Commence,” with his signature kindness, bravery, and yes, humor, J. Robert Lennon has captured what it is like to watch The Cosby Show today. In a mere 1,500 words he confronts the uncomfortable juxtaposition of a wholesome family comedy with the repeated violation of women’s rights, beings, and bodies.

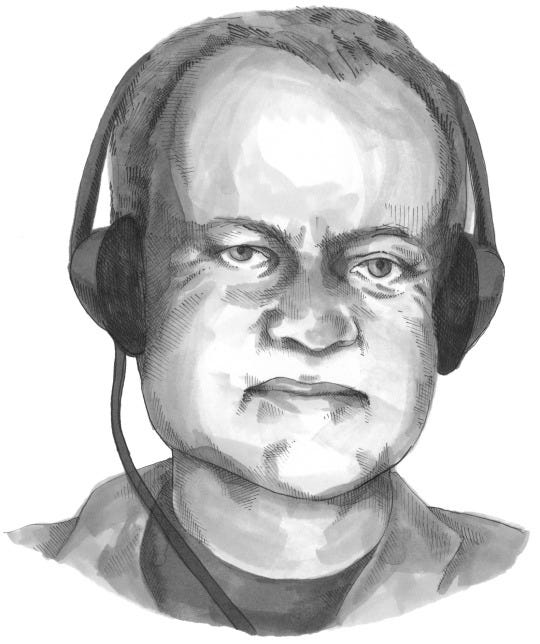

Pop culture has a way of folding in on itself, and in “Captain Stubing Has Collapsed,” Rob McCleary uses Frank O’Hara’s poetry to get his head around the many celebrity cameos of The Love Boat, from Andy Warhol to Lana Turner. McCleary writes, “With his appearance on the 200th episode of The Love Boat, Andy Warhol’s life is now a closed circle. A fact he does not understand consciously, but with the unwavering intuition of the true artist.”

Whether the culture circle is closing or infinitely spiraling back on itself in a tangled mess of allegory, reference, and the occasional progress may be the best question that emerges from this little experiment. In “Magical Negro #607: Gladys Knight on the 200th Episode of The Jeffersons,” Morgan Parker uses her own poetry to take on “The Good Life,” the title episode. “The good life is striking everyone,” reads the 200th episode summary, somewhat ominously. If “the good life” has stricken Parker, the question is what does it mean and how does she want it: “Sometimes eating a guilty salad/ I become a wife,” she writes. And later, “I want to be the first/ Black woman to live her life/ exclusively from the bathtub.” The idea that asking a talented poet to watch a late-stage episode of an outdated sitcom could yield a result like this is the kind of thing that helps me get out of bed in the morning.

Last but certainly not least, in “Retrieval,” Téa Obreht reflects on Frasier, a show which she admits she had on in the background while writing her New York Times bestselling novel The Tiger’s Wife. Unlike home videos or mixtapes, these Frasier reruns symbolize a fantasy of an easily accessed past: “I am thinking of the irretrievable: the fragility of all those homemade mixes, labored over by lamplight, shattered in moving boxes,” Obreht writes. Because the characters in Frasier have not lived beyond the final episode of the show, their pasts can be experienced without the painful distance wrought by the future.

I am so grateful to these writers, and to the many others we have published thus far in Recommended Reading, for allowing me, every week, to have a look at fiction being powerful, moving, relevant, and useful.

Halimah Marcus

Editor-in-Chief, Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading

The 200 Episode Club

And So, We Commence

by J. Robert Lennon

Cliff is trying to fix the doorbell. Today is Theo’s college graduation and a lot of people are coming over; they’re going to be ringing it, and he wants to make it play Miles Davis’s rendition of “If I Were A Bell.” It’s a good joke, you see, because it sounds like a normal doorbell at first, those four notes forward and back, before the quartet joins in. But the thing keeps shorting out — it plays only the opening notes, like a normal doorbell, and then it delivers, to his visitors, electric shocks. The bell doesn’t work. The joke doesn’t work. His house of love is a house of pain.

Cliff’s home maintenance projects seem simple and straightforward, at first: the dishwasher, the toaster, the bathroom tile. Then things go wrong. The tile, in particular, should have been easy. He pressed the thing into place and everything fell apart: the whole bathroom! Cliff has been feeling for some time as though everything, not just the appliances, were about to fall apart. He starts to do something with the best of intentions and it spools out of control. And lately he feels as though the people around him are humoring him. Just now, he invited the neighbors to graduation, even though Theo asked him not to. But he’s proud! He’s proud of his son. He wants everyone to be there. Theo must find more tickets, you see. That’s all there is to it. Everyone must be together.

For some time now, as a supplement to his medical practice, Cliff has been the star of a dark crime drama about a serial rapist. Dozens of episodes have been filmed. There is, of course, no studio audience. He’s not sure when the show is supposed to air, and his queries to the agency have gone unanswered. Indeed, the subject seems to make his agent uncomfortable. But why? Was it not his agent who got him the gig? He doesn’t remember how it all came about — can’t recall any audition — but it’s good, hard work, the best of his career. Sometimes, sitting at home on the sofa with Clair, he impulsively flips through the channels, trying to find it, hoping they’ve decided to broadcast it without telling him. He envisions a time when he’ll land on it by chance, and casually begin watching, and Clair will ask him what it is, and he’ll make one of his mugging shrugs that the audience loves, and then Clair will be drawn into the story and she’ll say, “My God, Cliff, is that you? You are incredible.”

Sometimes people talk about him in another room. He can hear them talking — can see them in the monitors — and they don’t seem to know. He feels as though they are mocking him — his mawkishness, his silly jokes, his distinctive sweaters. He can’t help himself: he rushes in, steals the scene. Before the rote smiles return to their faces, his family betrays their true emotions: they don’t like him. They want to leave. He can sense it. He has to make them stay. There must be a way.

He’s talking to his granddaughter, Olivia, who is soon to join her mother, Denise, in Singapore. He can’t remember why Denise is abroad, why Olivia is here. He seems to recall an argument. Denise was pregnant and Cliff sent her away — is that what happened? Cliff is uncomfortable with pregnancy. He doesn’t like to look at that. He tells Olivia he has a gift for her, but adds, “I hesitate to give it to you, because you may not leave. People really try to leave this house. But they keep getting sucked back in.” It’s reverse psychology, you see. The girl gazes at him, doubtfully. He demonstrates the phenomenon, which he calls “The Vacuum Effect,” by asking the child to walk out the door, then grabbing her sweater and holding her back. The child struggles; it reminds him of something. He begins to sweat. The audience is laughing. The director yells cut. Cliff heads to his dressing room, to be alone.

“How can you expect your father to contain himself?” he hears Clair ask Theo. Cliff is at the top of the stairs, listening; they are down in the living room. She’s talking about the graduation tickets, but there’s an edge to her voice. She means something else. She says, “He proceeded to hug every person on the dais, including the ushers.” Cliff remembers. His older daughter’s graduation, years before. One usher, a pretty one, ended up on his show. So did a policewoman he met, and one of his patients. He expected more gratitude from them, for getting them this acting work. But they disappeared from his life. He recalls their auditions: in hotel rooms, over drinks. Or was that part of the show itself? The man he plays, the rapist, is some kind of entertainer; perhaps he lures his victims with the promise of acting work? No — that’s not on the show. The auditions are real.

Or maybe they are the show.

He wishes the show would air. He would feel so much better if it did.

In the master bedroom, Cliff lectures the grandchildren on proper behavior among the adults at graduation. “There are certain things I don’t want you to say out loud anymore.” He offers examples. The audience laughs. He recalls saying this another time, in another context, and vertigo overtakes him. The children are staring. “Hammer time!” he shouts, and the children dance. The audience cheers.

“Don’t tell me to control myself,” Cliff says to his father, when he thinks the old man can’t hear. “I’m a grown man living in my own house.”

At graduation, they are all seated together on bleachers, and they are facing the studio audience, who are also on bleachers, and the two sets of people on bleachers gaze at one another under the artificial natural light.

“It’s over?” he asks Clair.

“It’s over, dear.”

“There’s nothing else?”

“There’s nothing else.”

But where is Theo? Where is the graduation? There is only the studio audience cheering them on as they themselves cheer on the son, and the graduation ceremony, that aren’t there.

He fixes the doorbell. He isn’t sure how he did it. One moment, it isn’t working; the next moment, it is. Miles Davis plays. The music seems to break some kind of spell. The house lights come up, and he and Clair parade, arm in arm, before the studio audience, the rest of the family trailing behind them, waving.

“Don’t leave me, Clair,” he says, low, into her ear. The audience is on its feet, cheering wildly.

She gives him a look.

“I don’t like my other life.”

“Are you all right?”

“Don’t,” he says.

“I don’t understand. What are you doing?”

“Don’t.”

She says, “Stop.”

“Stay.”

She says, “You’re hurting me,” and pulls away.

Copyright © 2016 by J. Robert Lennon. All rights reserved.

Captain Stubing Has Collapsed

by Rob McCleary

Lana Turner dumps Frank Sinatra then Ava Gardner dumps Frank Sinatra then Mia Farrow dumps Frank Sinatra so Frank sits at home watching Lana Turner on the 200th episode of The Love Boat with the sound turned off snarling the incandescent rage that is the home field advantage of the late-stage alcoholic.

The records no longer sell.

Frank Sinatra does not know why the Frank Sinatra records do not sell.

He rises unsteadily from the tattered recliner on skinny, old man legs. Bright yellow, old man pee spots the front of his tighty-whities.

Frank Sinatra does not know why the Frank Sinatra records no longer sell. Frank Sinatra cannot fathom why Lana Turner is on the 200th episode of The Love Boat. Frank Sinatra is not even sure what the fuck “The Love Boat” even is.

Or what the fuck “Menudo” is.

Frank Sinatra knows one undeniable fact: Lana Turner and Menudo are on the 200th episode of The Love Boat, and Frank Sinatra is not. He flails his skinny old man arms, knocking over the lamp and plunging the room into darkness, and his soul into a Dostoevsky midnight.

Frank Sinatra has collapsed.

With his appearance on the 200th episode of The Love Boat, Andy Warhol’s life is now a closed circle. A fact he does not understand consciously, but with the unwavering intuition of the true artist.

That’s him on the gangplank. A two shot with his first true love, Blotted Line (Candy Darling in an ill-fitting and hastily made costume of styrofoam and pasteboard). Warhol accepts the parameters of this reality: a small, angry lesbian with a .32 has been released into the labyrinth interior of the Pacific Princess.

Andy Warhol has had it with the flunkies at The Factory.

The itchy fright wig.

Silk screening Mick Jagger.

Andy Warhol has had enough. A touching scene where Blotted Line begs him not to go out into the ship.

Silk screening Mick fucking Jagger.

Andy Warhol has had enough of life. Andy Warhol has had enough of Andy Warhol.

Valerie Solanas finds him in the strange nightclub where Menudo performs before a packed crowd of predatory pedophiles and Lana Turner. Menudo, rehearsed and drilled to the point of dissociation by their manager, barely flinch when the shots rings out. Andy has been begging Lana Turner to let him make a silk screen of her. He is shot through both lungs, spleen, and liver, collapsing in an enormous pool of blood. Lana Turner sees the enormous pool of blood and swoons. Andy Warhol changes the channel. Now he is Andrew Warhola, the frightened boy from Pennsylvania, and this is his greatest work.

Lana Turner has been to lots of parties. And acted perfectly disgraceful. But she has never collapsed.

On the 200th episode of The Love Boat, Lana Turner collapses.

The 200th episode of The Love Boat has taken Captain Stubing to a bad place. He has been drinking heavily since the day they put out of port.

Flashbacks.

Nightmares.

Captain Stubing hasn’t spent his entire fucking life on the fucking Love Boat. Captain Stubing has been in the shit. Captain Stubing has hosed what’s left of his buddies off carrier decks. For 199 episodes he has hoped to become famous for a mysterious vacancy. But the fucking white shorts, white knee socks, and white shoes have killed the dream. No one ever becomes famous for a mysterious vacancy in white shorts, white knee socks, and white shoes.

“My life is a final chapter no one reads because the plot is over,” he announces over the p.a. system, his wracking sobs a maudlin echo down the hallways and decks. The hallways are empty. The .32-toting lesbian still at large. Still angry. The All You Can Eat Seafood Buffet is untouched. The whirlpool unused.

Frank Sinatra has collapsed.

Andy Warhol has collapsed.

Lana Turner has collapsed.

Captain Stubing has collapsed.

Oh Captain Stubing we love you get up.

Copyright © 2016 by Rob McCleary. All rights reserved.

Magical Negro #607: Gladys Knight on the 200th Episode of The Jeffersons

by Morgan Parker

Privilege is asking other people

to look at you. I like everything

in my apartment except me.

What is the point of something

that only does one thing.

I mean I need to buy a toaster.

My life is a kind of reality.

When I get bored, I close the window.

By the way what is a yuppie.

Here I am, two landscapes.

My tattoo artist says I’m a warrior

with pain. I tell her we can manifest

this new moon in six months.

When I’m rich I will still be Black.

You can’t take the girl out of the ghetto

ever. It’s too much to ask to be

satisfied. Of course I sing

through the struggle. My problem is

I’m too glamorous to be seen.

How will I know when I’ve made it.

In the mirror will I have a face.

How long does a good thing last.

Sometimes eating a guilty salad

I become a wife.

Let me be the woman

who takes care of you.

Weezy and George in drapes

and crystal silverware.

By the way predominantly white

means white. I want to be the first

Black woman to live her life

exclusively from the bathtub.

Making toast, enjoying success

despite my cultural and systemic

setbacks. I was raised to be

a nigger you can trust.

I was raised to be better

than my parents. In a small house

with a swamp cooler

I touched myself. I wanted to be

in the white mom’s carpool.

My cheek against something new

and clean. I clean my apartment

when I am afraid of being

the only noise.

Everyone I know is a Black man.

Me I’m a Black man too.

Tragically, I win. It is a joke.

I always require explanation:

Life, Dope. I am so lucky to be you.

When something dies,

I buy a new one.

Copyright © 2016 by Morgan Parker. All rights reserved.

Retrieval

by Téa Obreht

On a cool spring day, in the midst of a half-hearted organizational venture through the citadel of cardboard boxes in my mother’s basement, I watch my brother unearth a 1999 Sony Discman. It’s mine, of course — or it was, once. I haven’t seen or thought of it since at least 2005, but I’m stunned by the clarity with which I can recall the texture of its buttons; the thwap of the clamshell lid dropping into place; the buzz of the gears; the Nero-days terror of not knowing whether the display would flash the digital timer, or that soul-crushing admonition: NO DISC. I’m pretty sure I could easily have gone the rest of my life without revisiting whatever sensory archive has just flown open, and I don’t know whether to feel grateful for my brother’s find. He’s examining the Discman gravely.

At fifteen, my brother is a walking affirmation of his Slavic heritage: six-two, well on his way to a goatee, so broad-shouldered and self-possessed and devoid of gangly teenaged awkwardness that his refusal to accept congratulatory pints at my wedding last year stupefied the bartender. From the other room, a familiar laugh track has reached the kind of pitch that indicates Niles Crane is talking, a reminder of my only condition for helping with my brother’s chores: that I be allowed to work as I do at home, with Frasier in the background. I’ve told myself that I’m doing this partly for the satisfaction of irritating a teenager who thinks he’s too cool; but that’s not true. I love Frasier, and I want him to love it, too, though I suspect he’s a good few years from being able to. He’s been a good sport about it so far. He thinks the curmudgeonly dad and the little dog are funny enough. He chuckles every once in a while, but his sufferance has done little to hide that he considers it a show for old people. Now, he holds up the Discman and says, “What’s this?”

I want to tell him that I probably smuggled it into the hospital the day he was born to remedy the solitude of the waiting room.

Before I answer, before I’ve even held out my hand, I am thinking of the irretrievable: the fragility of all those homemade mixes, labored over by lamplight, shattered in moving boxes. Or the VHS tape chronicling four years of college ballroom performances, obliterated by the premature declaration that I’d checked my TV/VCR two-in-one, and yes it was ready for the yard sale. And what about all those yards of waterlogged tape, that video of my brother in his first walker, awestruck by the huge, pink bubblegum orbs I’m inflating for him? I know that video is real, I remember it — but he’s never seen it, so he’ll never have any sense of this moment we shared when he was too small to stand.

I dole out some absolute diamond of sisterly wisdom: “You see, you belong to an era wherein the mere jolt of memory can prompt physical retrieval: all the pictures and songs of your youth are there, somewhere, in a perpetually accessible space that obliterates the need for reliquaries.”

I want him to understand that, when these things went missing in my day, their disappearance was absolute. Only now it’s a lecture about his generation; now, it’s worse than making him watch Frasier. “But no, not really,” I want to say, “it’s actually just like that time on Frasier” — which is something loved ones hear from me often. And it’s true, it is just like that time Frasier can’t celebrate his 200th show on KACL because Daphne has ruined the irreplaceable tape of June 14th 1996’s show — or rather, Daphne’s new boom box has ruined it — and Daphne’s ruse to replace the tape with The Best of Hall and Oates has failed, taking with it the possibility of his ever having a complete collection of The Doctor Frasier Crane Show. “Oh, all his crap is treasured!” Martin says, and I laugh every time, because I know how the episode ends — but I feel for him. Frasier is gutted by the disappearance of something he admits to Niles he probably never intends to replay, because he couldn’t now, even if he wanted to.

Copyright © 2016 by Téa Obreht. All rights reserved.