interviews

The City Where One Wrong Word Can Kill You

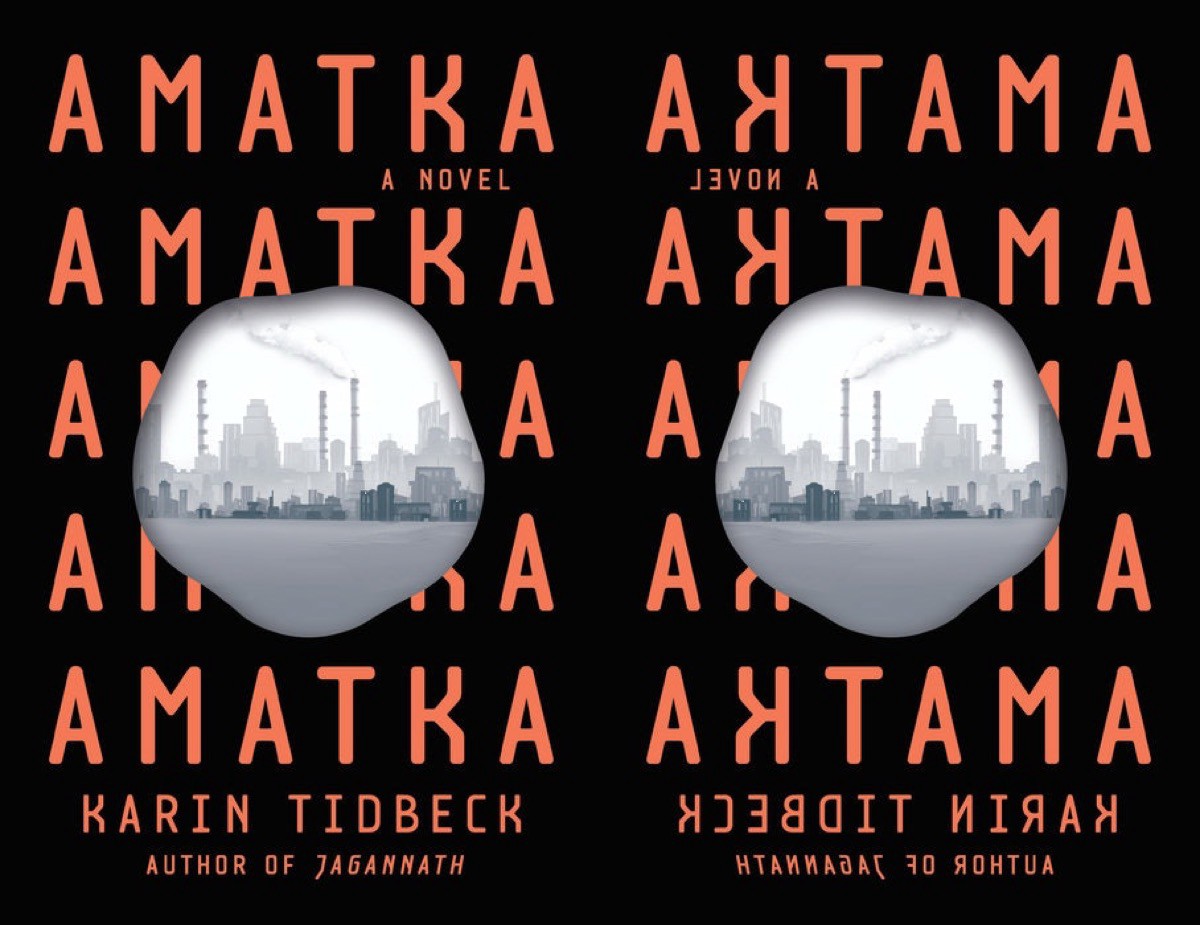

Two writers discuss Karin Tidbeck’s weird new novel ‘Amatka,’ in which society relies on language

Double Take is a literary criticism series in which two readers tackle a highly-anticipated book’s innermost themes, successes, failures, trappings, and surprises. In this edition, Amy Brady and Adam Morgan explore the dark, surreal novel Amatka, by the Swedish master of weird fiction, Karin Tidbeck.

First introduced to English readers by Ann and Jeff VanderMeer (via her short story collection, Jagannath), Karin Tidbeck’s novel Amatka follows an investigator named Vanja who travels to the frigid colony of Amatka, where language — both written and spoken—has immense power. But beneath the city’s peaceful veneer, long-held secrets are beginning to surface that could destroy everything. Amy Brady and Adam Morgan discuss Tidbeck’s unique brand of worldconjuring, her Scandinavian influences, and how successfully she incorporates elements of mystery, surrealism, and poetry.

Amy Brady: When Vanja first arrives at the Amatka colony, I wondered where we were in time and space. In some ways, Amatka is much like our world, but it also differs in significant ways: Amatka is one of only four colonies of human beings in existence (a fifth colony, we learn, was destroyed), and almost every material thing — including furniture, eating utensils, even the buildings themselves — is made out of a strange sludge that takes on whatever shape it’s labeled with. To form a wall, for instance, a member of the colony would point at the sludge, call it a wall, and then write the word WALL on it for good measure. One of Amatka’s biggest collective fears, then, is calling something by the wrong name.

This is a world where language is a source of tremendous power.

What’s fascinating is that compared to some dystopias — say, Gilead in The Handmaid’s Tale — Amatka doesn’t always seem so bad. Yes, on the one hand, women are almost forced to have children, who are then raised independently of their parents. But on the other hand, women are allowed to hold positions of power, no one bats an eye at same-sex relationships, and no one seems to be going hungry, despite their limited resources.

So as the story unfolded and Vanja became increasingly unhappy with what she perceived as limits to her freedom, I found myself wondering: Is escaping the colonies really a better choice? I can’t remember the last time I felt this ambiguous about a dystopian world’s moral framework or its potential for change. And that feels like an exciting shift for the genre.

I can’t remember the last time I felt this ambiguous about a dystopian world’s moral framework or its potential for change.

Adam Morgan: You’re right, Tidbeck’s dystopia isn’t as violent as the ones we’ve become familiar with in popular culture. The horror of Amatka is much quieter — between the lines and behind the scenes — but I could still feel it from the first pages, when Vanja is traveling on a windowless train with no idea what kind of landscape awaits her outside. That quiet evocation of dread hangs in the air throughout the book, and it reminded me of Brian Evenson’s short stories…so much so that I pictured this novel’s librarian, Evgen, as Brian Evenson.

I did wonder if a world where families are forced to sever emotional ties soon after childbirth was an exaggeration of Tidbeck’s native Swedish culture, which really de-emphasizes the role of family in public life, at least compared to the U.S. and the U.K. Amatka’s authoritarian system of government, however—the invisible “committees” issuing orders from a secure tower — struck me as the inverse of Scandinavian egalitarianism, so I can see why a progressive writer in Malmö might find fascism (even well-meaning fascism for the “greater good”) quite disturbing.

As to where we are in time and space, at first I thought Amatka was just a fictional Scandinavian city in some bleak future where parts of the world were slowly being recolonized. And then I thought it was an alien planet. And then I thought it was some kind of O’Neill cylinder in space. By the end of the book, I still wasn’t sure, and while I typically delight in narrative ambiguities, the trail of bread crumbs Tidbeck left us regarding Amatka’s geography (or should I say cosmology?) created an appetite that was never sated.

Perhaps I expected too much from a 200-page novel, though the scope and level of detail here sometimes felt like a short story stretched over too much mycopaper (that’s an Amatkan joke — trust me, it’s hilarious once you’ve read the book).

How did you feel about balance of mystery, suspense, and closure?

AB: The mysteries of what, exactly, the shape-shifting goop is and where it came from delighted me. By telling us so little, Tidbeck created an unnerving tension that snaked through the whole book. I kept wondering: Is the goop alive? Will it exact revenge on the humans who force it into shapes? We never get concrete answers, and I like that choice, because it suggests that the characters might still be in danger, even by the book’s end. A more pat conclusion that explains away the mystery of the goop would have been too heavy-handed for my taste.

But that said, there were other enigmas that felt less connected to the central narrative and left me wanting more satisfactory explanations — the machinery in the tunnels, for example, and the nightly freezing of the lake. Tidbeck describes these things with brilliant detail, but I felt like I was never rewarded for my curiosity.

By telling us so little, Tidbeck created an unnerving tension that snaked through the whole book.

One thing I really loved about the book was its celebration of poetry. I suppose the ending could be interpreted (without giving too much away) as a triumph of poetic language over the prosaic. What did you make of the fact that even in post-apocalyptic Amatka, where resources were limited, poets managed to publish their work? And a follow-up question: If you could make manifest any poem by writing it on a heap of mystery goop, which poem would you choose?

AM: That’s a really good way of putting it: I never felt rewarded for my curiosity. And it’s not that I wanted “answers” to the mysteries in a teleological way (e.g., the finale of LOST), but I did want greater detail and more exploration of the environment, since Tidbeck drops all these hints that there’s more than meets the eye.

In Jeff VanderMeer’s Annihilation, for instance, even if we ignore the rest of the trilogy, he rewards our curiosity about the tunnel and the crawler by giving us a very detailed encounter before the end of the novel. We don’t get “answers” (who needs those?), but he gives us the experience we’ve been craving since page one: to explore and experience. We never really got to explore or experience Amatka beyond vague impressions, though Tidbeck certainly spark our curiosity.

The poetry metaphor is a good one, given that this book (and Amatka itself) operates on what Kelly Link would call night-time logic, which certainly makes its way into speculative fiction but has always felt poetic to me. I found it really interesting that, as you say, a civilization with only so much paper would preserve poetry, though perhaps that’s another artifact of Tidbeck’s Scandinavian foundation. Poetry, and literature in general, is not the niche leisure market there that it is here in the States, and many Scandinavian writers make a decent living thanks to massive governmental investments in the arts.

I’m wondering too about your thoughts on the end of the book. Without giving anything away, Vanja and Amatka’s fate felt rather deus ex machina to me. While I really enjoyed the narrative threads Tidbeck had woven for the first 150 pages (as well as the form they took), most of them simply dissolved in the last few chapters, like unmarked tubes of toothpaste (last Amatkan joke, I swear).

AB: Your insights into how Amatka’s civilization maps ideologically on to Scandinavia’s are especially interesting in light of the region’s dominance of the 2017 World Press Freedom Index. Of the countries surveyed, Norway tops the list with the most media-related freedoms, followed closely by Sweden, Finland, and Denmark. This is a region that values its freedoms to speak and write, and Amatka, for all its sci-fi and fantasy elements, holds a similar reverence for language. Capital punishment in Amatka, after all, isn’t death — it’s losing the ability to form words.

As an American reading this book, I couldn’t help but think of how our own freedoms of expression are under attack: there’s the administration’s treatment of the press, the possible elimination of the NEA and NEH, and of course the systemic weakening of our country’s humanities and journalism programs. These are not the signs of a nation that values language. Wanna guess where the United States falls on the Index? Forty-three. We’re number 43.

So, what did I make of the ending? I think you’re right — it left a lot of ends loose and twisting in the wind. And that was frustrating. But looked at another way, the story also culminated in a poetic vision that seemed very much in line with the book’s suspicion of literalism. For me, at least, the climactic ending was hard to “see” in a way that the rest of the book wasn’t: The action was blurry, and Vanja’s participation in it was at times hard to decipher. But rather than weakening the story, the vagueness, I felt, reinforced its themes. To paraphrase Emily Dickinson, Tidbeck told all the truth about Amatka in those final moments, but she told it slant.

As an American reading this book, I couldn’t help but think of how our own freedoms of expression are under attack.

The book left me feeling some ambiguity toward Vanja, however. There’s so much to admire about her (especially her bravery), but at times she seemed to be making choices based on her own, nebulous dissatisfaction with life instead of anything rooted in society around her. What did you make of her?

AM: I appreciated Vanja’s agency, particularly after reading so much dystopian fiction where the heroine just gets bounced around from horror to horror. In terms of characterization, though, Tidbeck’s approach reminded me of science fiction writers like Arthur C. Clarke and Kim Stanley Robinson, for whom protagonists often serve as neutral point-of-view vessels. But I don’t mean that as a critique, and here in Amatka (as in 2001: A Space Odyssey and Aurora), Vanja’s aloofness is narratively justified. On some level this is a story about the horrors of emptiness, wordlessness, and formlessness, after all.

In the end, despite the places where my appetite wasn’t quite sated, I think we both really liked this book. It’s a unique reading experience — a sharp, understated glimpse at a terrifying world. The fact that I wanted more is a testament to how fascinated and invested I was in what’s there. I hope Tidbeck’s next book is 100–150 pages longer. Either way, I’ll be reading it.