Lit Mags

The Weirdest Mom in the Neighborhood

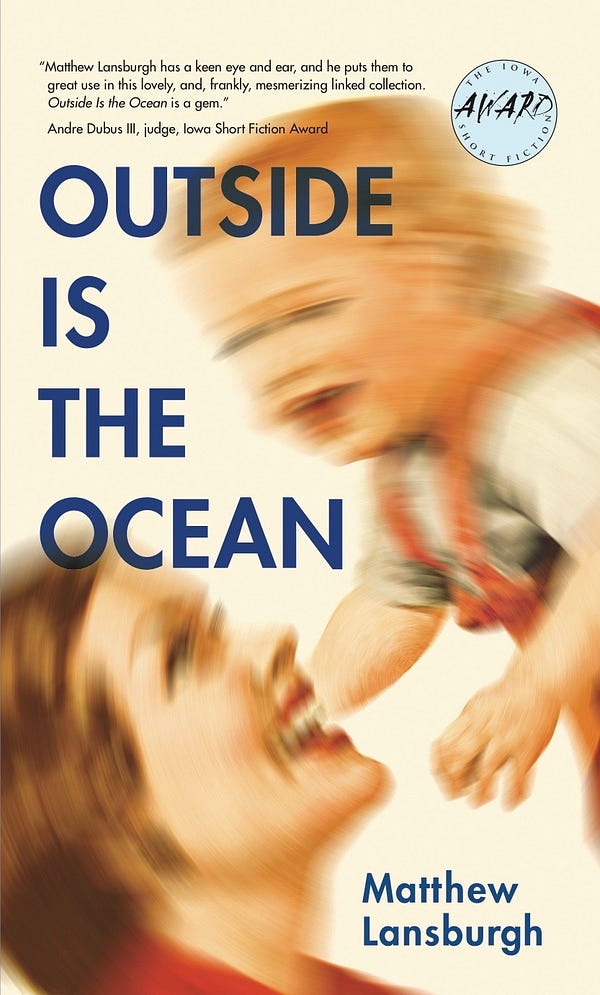

Paul La Farge recommends Matthew Lansburgh’s story about the happiest unhappy family

AN INTRODUCTION BY PAUL LA FARGE

It’s been nearly a century and a half since Tolstoy dismissed happy families from the field of literary curiosity, and although I’m reluctant to argue with Tolstoy about anything, I can’t help thinking that stories about unhappy families are now so abundant that they too are becoming hard to tell apart from one another. Who had a happy family, anyway? Who has even met a happy family? Every family’s closets are packed with skeletons; you’ll find the overflow in the spare bedroom, the living room, the basement — don’t look in the basement.

It takes a rare talent to make a story about difficult parents and troubled children stand out against such a backdrop,  and I am happy to report that Matthew Lansburgh has that talent in abundance. His collection of linked short stories, Outside Is the Ocean, revolves around one of fiction’s great bad mothers, Heike, a German-American who survived the Second World War only to inflict what seems, at times, to be nearly equivalent terrors on her son and adopted daughter. Self-centered, vain, erratic, and yet passionately convinced of her own righteousness, Heike is the permanent center of her own terrible party, the victim of so many monstrous everyday injustices that she’d be beatified if only anyone knew, or cared.

and I am happy to report that Matthew Lansburgh has that talent in abundance. His collection of linked short stories, Outside Is the Ocean, revolves around one of fiction’s great bad mothers, Heike, a German-American who survived the Second World War only to inflict what seems, at times, to be nearly equivalent terrors on her son and adopted daughter. Self-centered, vain, erratic, and yet passionately convinced of her own righteousness, Heike is the permanent center of her own terrible party, the victim of so many monstrous everyday injustices that she’d be beatified if only anyone knew, or cared.

Heike could be a monster, but Lansburgh — even as his stories draw energy from her wild terribleness — is wise enough to render her as a person. As we see in the following story, “Gunpoint,” he accomplishes this in part by remaining aware, at every turn, that people define each other as much or more than they define themselves. If Heike is terrible to her son, the book’s other protagonist, it’s because he gets some mileage out of his own grievances; if the son betrays Heike constantly, it’s because she sees everything as betrayal. Another reason why the stories succeed in moving — and indeed captivating — the reader is that Lansburgh keeps his emotional palette big. There’s plenty of anger in Outside Is the Ocean, and plenty of thwarted searching for a connection which is perhaps impossible to achieve. But there’s joy also, and humor, intimacy, and relief.

You might find, as I did after finishing the collection, that Lansburgh does much more than write about a monstrous parent in a new way. His great achievement is that he complicates the creaky old opposition between happy families and unhappy ones. Lansburgh shows how much room there is, even in bad circumstances, not only for survival, but for tolerance and even for love.

Paul La Farge

Author of The Night Ocean

The Weirdest Mom in the Neighborhood

Matthew Lansburgh

Share article

“Gunpoint”

by Matthew Lansburgh

The summer before I started seventh grade, not long after Patty Hearst was sentenced to thirty-five years in prison, my mother married a man who owned a ranch house with a yard full of lemon trees. As far as she was concerned, she’d hit the jackpot. Gerry didn’t drink, he had a job, and, whenever we went out to eat, he always picked up the check. After dating a string of losers, after moving from apartment to apartment at least once a year for nearly a decade, my mother told me — three weeks into her new relationship — that, no matter what, we could not spit on the luck God had given to us. “This chance is once in a lifetime,” she said.

My mother met Gerry on a ski trip organized by Amway. She put the vacation on her credit card and arranged for me to stay with a family that lived down the street. “Bingo,” she announced on the phone, four days after she left. “I met someone perfect. He’s a little tight-lipped and has a tummy, but he’s an accountant, and he owns a condo in Mammoth.” A few months later they got engaged and we moved from Ventana Beach down to L.A.

In retrospect I realize that Gerry had no idea what he was getting himself into. He liked routine, he hated conflict, and he wasn’t used to dealing with difficult people. My mother, who immigrated to the United States from Germany at the age of twenty to work as a maid, has always been the kind of person who doesn’t take no for an answer. Within a week of our move, she’d butted heads with Gerry’s neighbor Sandi Sarconi by borrowing her rake without asking permission. My mother happened to be using the rake just as Sandi drove down the street in her red BMW. The incident probably wouldn’t have been a big deal if my mother had simply apologized, but she tried to justify herself, explaining that Gerry’s rake was too rusty to work properly, then using the discussion as a way to horn in on Sandi’s weekly doubles game with Carol Wallace, a woman who lived up the block, and two other women my mother had been wanting to meet.

It promptly became clear to everyone involved that Sandi and Carol did not like my mother’s style — didn’t like the fact that my mother cut her own hair instead of going to a salon; that she brought wiener schnitzel, rather than lasagna, to Carol’s annual potluck; that she let Gerry’s dog, Goldie, defecate in people’s front yards. In September, Carol called just as we’d sat down to dinner.

“Why hello there,” Gerry said when he picked up the phone. He was wearing the same thing he put on every night after he got home from the office: worn jeans and a flannel shirt. “Is that so? I see. That’s unfortunate. Yes, of course, I’ll have a talk with her.”

My mother, who’d been telling Gerry a story about how the cashier at Vons had tried to overcharge her for a bag of oranges, was wiping up the gravy on her plate with her finger. She had a worried look on her face, a guilty look. I’d seen the expression plenty of times.

“Carol says Patti Schneider saw you laying out in their backyard with your top off,” Gerry said when he hung up.

“Really?”

“Yes, really. Did you go swimming in her pool, Heike?”

“I went for a quick dip. Is that such a crime? I tried to knock, but no one was home.”

“She says she saw you lay out on the deck and take off your top.”

“That’s ridiculous,” my mother said, getting up from the table and clearing the plates. “I simply pulled down the straps a bit. She’s just jealous of my beautiful figure.”

Gerry took off his glasses and studied them, as if he’d been socked in the face.

“Everyone hates me,” my mother complained to him a few weeks later. “You have your job. Stewart goes to school. I have nothing. I need a good friend.” My mother had made Gerry his favorite meal — meatloaf with spätzle and fried onions — and she had tears on her cheeks. Gerry wasn’t stupid. Even before she made the request, he knew what she had in mind. She wanted him to let Sabine, a woman my mother had met at the German bakery in Hawthorne, move in with us. Sabine was from Munich, and, after being evicted from her apartment because she had too many cats, she’d recently moved to a motel that rented rooms by the week.

“No, Heike,” Gerry said. “There’s not enough room.”

“Don’t be such a stick in the mud. We can put a futon in your office. I saw one for sale at the Goodwill — only fifteen dollars, including delivery.” Gerry stared at my mother, using his fingernails to pluck the stray hairs that grew from the edge of his ears. “Wait till you meet her. She has warm eyes and a kind smile. Your heart will go out to her.”

After dinner, when Gerry still hadn’t given in, my mother became semi-hysterical. “You don’t know what it’s like for me here! Sometimes I almost kill myself. Is that what you want? To come home and find your wife hanging from a rope?” I was in my room studying, but I could hear everything. It wasn’t the first time I’d heard my mother trot out the suicide card.

“Enough!” Gerry shouted. I got up from my desk and looked through the crack between my door and the wall in time to see him storming off to the garage.

“Model airplanes,” my mother yelled, still in tears. “My husband loves model airplanes more than his own wife!”

We drove to Inglewood to visit Sabine on a Saturday morning. My mother had gotten up early, made French toast, and put on the halter top she used to wear when she had to take her car in to get fixed.

“Do I really have to go?” I asked as I watched my mother put her plate on the carpet so Goldie could lick up the Mrs. Butterworth’s. I hated the fact that my mother let the dog eat off our dishes, and I was convinced we’d end up with worms.

“Have to go? It’ll be fun. Gerry takes us to Marie Callender’s for lunch.”

“But I have homework.”

“Ach! Who does homework on Saturday? Come on now. Behave or you won’t get any pie.”

I reminded her that I didn’t like pie and said something about the science fair project I needed to work on, and then, when I knew I was fighting a losing battle, I went to my room to change out of my pajamas. The truth is I hadn’t wanted to stay home to study. I was hoping that Jason McFarland — a kid who’d moved into the house next to the Wallaces in June — might knock on our door. Jason and I weren’t friends exactly, but sometimes he’d stop by to see whether I wanted to go out to the bushes behind our house and look at a stash of dirty magazines he’d stolen from his father. For some reason, Jason had decided that a place at the back of our yard, behind the lemon trees, was the perfect hiding spot for his dad’s porn: three Penthouse magazines full of lurid photos of Amber Williams and Tonya Lee and Felicity Light and other women whose names I’ve forgotten, in poses that for many years I could recall with surprising clarity, including the one of Tonya next to a fire truck with a bare-chested man in suspenders who had hair leading down to his navel and biceps that looked like the gym teacher’s.

The first few times Jason and I snuck out back, usually after school when my mother was running errands, Jason led the way. I watched, the branches of the lemon trees digging into my back, while he unearthed the mildewed treasures and flipped through their pages. Jason was in eighth grade, only a year ahead of me, but already his voice had changed and he boasted an Adam’s apple. I remember leaning close to him, ostensibly to get a better look at the photos — so close that sometimes my arm grazed his shoulder or forearm or some other part of his body. I studied the blond hairs that had begun to sprout from his cheeks and his upper lip. I remember wondering whether he had a boner.

I stayed still, nervous that we might be caught or that Jason might notice me gazing at him. The dirt was damp and soft, and its earthy smell rose up to meet the scent of the lemons. I imagined my mother coming into the garden and calling out to us. “Stewart!” she yelled once, after getting home from a tennis game and not finding me in the house. “Are you here?” I heard her voice carry across the lawn and the hedges, through the thicket of branches, and I froze.

“Don’t be such a fag,” Jason said, while she was still outside in her yellow Fila skirt, shouting my name. “She’s not gonna find us.” His breath was warm and made my ear tingle.

Sabine’s motel was even more rundown than I expected. It was on a busy intersection, and the office windows were covered in bars. The only parking space was next to a group of guys in tank tops sitting on their motorcycles, and before Gerry had gotten out of the car, one of them called my mother baby and made a loud kissing sound.

“How long is this going to take?” I asked.

“That’s enough! Do you want to ruin the only friendship I have?”

I trailed my mother and Gerry — who walked on the edges of his feet, complaining that his arches hurt — across the parking lot, toward a room with a door that looked like someone had tried to pry the knob off. My mother knocked, and a tall woman in a skimpy robe answered. “Heike, Liebchen,” she exclaimed. “You came after all. Careful the cats do not run outside.”

When I reached out to shake Sabine’s hand, she leaned forward and embraced me. “Heike, you didn’t tell me Stewart was so handsome! I bet all the girls are chasing after him right and left. How wonderful to finally meet you, my little Prince Charming.”

“Likewise,” I said, trying to keep some distance between her chest and mine.

Sabine’s room was small and reeked of urine; the curtains were drawn, and the only light came from a small lamp next to the bed. Two litter boxes covered the carpet next to the dresser, and neither looked like it had been emptied in days. At the foot of her nightstand sat a bowl of dried cat food and a dish of water with something bloated floating on the surface.

“My goodness,” said Gerry, gesturing toward the cats. “Are they all yours?” Two of the creatures were up on the dresser, trying to climb into a box of full of papers.

“Yes, these are my babies,” Sabine said. She stroked one on the back and grinned, exposing a set of teeth that were too large for her mouth.

“Aren’t they cute?” asked my mother, as she picked up a white kitten and cradled it like an infant. “Feel how soft.” Gerry put his hand out tentatively to stroke the cat’s fur. “See, mein Schatz. Gerry takes a liking to you.”

“They are my blessing,” said Sabine. “Without my Bübchen, I would not know how to survive. I do not have such a nice family.” Sabine looked at me and then, before I could pull away, she put her hand on my thigh. I felt the skin of her palm, cool and moist as a raw chicken cutlet. “My ex-husband, Rolf, and I tried to have a child for many years. We wanted a son.” Her robe had come open a bit, and I glimpsed a terrifying expanse of white skin.

Gerry told Sabine that she lucked out finding a hotel that allowed pets.

“Ja. They do not mind die Bübchen. My old landlord was quite cruel. He continually nailed papers to my door demanding that I must move out of my house. I was a good renter. I paid him on time. I was clean, but he insisted I leave. I am sure it was because of the cats. Only in America would such a thing happen. Gerry, do you know if this kind of thing is legal to do?”

Gerry started to respond, but my mother interrupted. “Of course it’s illegal. What one does in one’s own home is no one else’s business. How could he have objected to a few kittens? Does he also throw his wife out if she has twins?” My mother and Gerry sat in plastic chairs while I sat on the bed next to Sabine. The air was thick with dander, and my eyes were watering; I felt like I’d been locked in a bunker. I sneezed twice, insisted I was having an allergic reaction, and asked whether I could wait in the car.

“Fine, Mr. Party Pooper. Just don’t get anything out of these vending machines. We eat lunch soon.”

Outside, the Hells Angels were gone, but two teenage boys were now doing wheelies on their bikes. The boys looked like they were in high school, and they didn’t have shirts on. I tried not to stare but found myself glancing furtively at them, partly out of fear that they might ride over and do something to hurt me, partly because any guy who’d already gone through puberty caught my eye. Their nipples were larger than mine, and I could see veins on their arms. I myself was a late bloomer, and the fact that I hadn’t sprouted as much hair under my arms or around my crotch as other kids in the locker room caused me perpetual angst. I stood next to the car wondering whether I should go back to Sabine’s room to ask for the keys. A minute later one of the guys shouted something in Spanish, and they both laughed. I stared at the fender of Gerry’s Oldsmobile, afraid to look up. I tried to wedge my right foot under one of its tires, pushing the front of my shoe into the space between the rubber and the asphalt until my toes hurt. Then I heard what sounded like a pebble hit the windshield. I looked up and saw the bigger of the two kids throw something else in my direction as they sped away, shouting maricón.

My mother kept telling me I should be happy she married Gerry. She said that Gerry had saved us from being homeless, but Gerry wasn’t the kind of father I’d hoped for. He didn’t mess up my hair with the palm of his hand when we were standing in line at McDonald’s or tickle me until my stomach hurt. He didn’t take me Boogie Boarding in the summer. Most of the time, he just wanted to sit in his easy chair and be left alone.

Occasionally I wondered what it would feel like to be kidnapped. I imagined men wearing masks driving up in a van and forcing me inside at gunpoint. I pictured them pinning me to the floor and taping my mouth shut, sending my parents a ransom note like I’d seen on TV. I played out various scenarios in my head: my mother calling my father in Colorado, pleading with him to send money; my father flying in to meet the police, then driving around town with my mother, putting up posters with a photo of me; my parents standing next to each other in a house I’d never seen — a two-story house with a nice living room and a pool in the back — surrounded by men in FBI uniforms, wearing headphones and hovering over tape recorders they turned on each time the kidnappers called.

Over the next several days, as I lay in bed at night trying to fall asleep, I heard my mother and Gerry having more sex than usual. My room shared a wall with the master bedroom, and I often heard, if not their exact conversations, then at least the murmur of their voices, punctuated with my mother’s occasional laughter and yelps. I knew what my mother was up to. She’d also been posting fliers at the grocery store and the laundromat advertising “potty-trained” kittens.

“He’s just worried they won’t get along with Goldie,” she’d confided. “If we find them a family, he’ll come around.” She extolled the cats’ beauty to anyone who would listen: people she met when she was hitting against the wall of the tennis courts at the park; the Sarconis’ gardener, Frank Herrera; anyone else who happened to cross her path. Then one afternoon — I remember it was a Wednesday, the day I had to drag the garbage cans out to the street — my mother came into my room while I was cutting out photos of Mayan ruins for a social studies project. “Guess what?” she said, standing in the doorway in her bikini. “This Saturday we have a little surprise.”

She had some kind of heavy cream all over her face, something she put on whenever she went out to the garden to take a sunbath. I asked her what kind of surprise.

“We have your friend Jason over for dinner,” she said, giving me a sheepish grin.

“Jason? What do you mean?”

“Well, I know how much you like him, and I thought I surprise you by inviting his family over for dinner. I called his mother this morning.”

“Are you insane!”

My mother insisted that she was just trying to be a good neighbor, but I knew what she was scheming. The thought of having her try to unload some of Sabine’s cats on Jason’s family, of having them watch my mother prance around in her dirndl, trying to yodel and telling the stories she always ended up telling complete strangers — stories about how, during the war, even a potato was a luxury and how the husbands of the women who hired her when she moved to America tried to have sex with her in the pantry or the gazebo or the garage — made me want to throttle her.

That night, I lay awake listening to the ticking of my clock. I heard my mother and Gerry go to bed, and in the distance I heard the sound of a train, like a foghorn out in the ocean. Periodically, I got up and turned on the light to see what time it was. I had a math test the next day, and I kept going over word problems in my head: questions involving the number of ice bricks necessary to build an igloo of a given size, or the quantity of paint required to cover a specified number of walls.

I thought about how my homeroom teacher, Mrs. Wilson, told me I was only allowed to ask her two questions per day and how she’d started making a clucking sound whenever I raised my hand. I remembered how even Jackie Fleischman, the girl with the leg brace, laughed when I asked Mr. Gutierrez whether something he’d said was going to be on the test. Recently I’d seen Jason hanging out with Sam Espinoza, a kid who carried his skateboard around with him all the time and who sometimes threatened to beat me up if I didn’t give him a quarter. I wondered how long it would be until Jason figured out that everyone at school thought I was weird.

As it turned out, I didn’t have to wait until Saturday for things to unravel. Two days later, I was walking home from school when I saw a police car in front of the Wallaces’ house. Even from the top of the hill I could see the car’s red and blue lights. School had ended an hour before, but I’d gone to the library to check out some books on Andrew Jackson. As I came down the hill, after it was too late to turn around and retrace my steps, I saw my mother and Sabine on the Wallaces’ lawn, in their bikinis, being questioned by the police. Carol Wallace was standing next to them, gesticulating wildly while, to my horror, Jason and his sister stood on their porch, eating ice cream sandwiches and watching the spectacle unfold.

“Stewart!” my mother shouted. “Call Gerry. These men are trying to arrest us!” My mother’s bikini was emergency orange, and the top was so tight the entire world could see her nipples. It was her favorite bikini, the one she called her orange knockout. Immediately I ran down the street, certain that Jason and his sister were watching me flee.

I arrived home out of breath and stormed through the house. Goldie got up from under the table and lumbered over to me, wagging her arthritic tail. “Out of the way, pig!” I yelled as I grabbed the phone to dial Gerry’s number. On the third ring, his secretary picked up and told me he was in a meeting. “Is there a message?” she asked.

“Can you tell him his wife called? She has a question about dinner.”

When I hung up, I stood in the living room wondering what to do. Goldie was standing by the back door, staring at me. I looked at the bowl of lemons that my mother kept on the kitchen counter and the bottle of coconut suntan lotion. I imagined turning Goldie into a dragon and getting on her back and flying away. I wished I could turn the lemons into hand grenades and the suntan lotion into a flamethrower and burn Gerry’s house to a crisp.

Sometimes I wished my mother had never met Gerry. I thought about how, when we first moved to L.A., my mother kept saying that the master bedroom, with its brown shag carpet and embroidered pillows, smelled like Gerry’s wife, Fern, was hidden away in one of the closets, recently deceased. I remembered how my mother took all the sheets and blankets out of the bedrooms and washed them on hot, how she used so much detergent that it smelled like someone had dumped a bottle of perfume into the Maytag, how she kept the windows open all day, even when it was raining. I remembered her asking Gerry whether he appreciated everything she was doing to make his house nicer. More livable was the term she used. I remembered her getting up on the step stool with a bucket of bleach and scrubbing all the cupboards.

At first Gerry thanked her and said the house had needed a good cleaning, that he’d forgotten how dirty things can get if you don’t stay on top of them. Then one day Gerry was in the family room, looking at his bookshelves, and he asked my mother where she’d put all his magazines. “Were you still reading those?” she asked. “I thought you were done with them, they were so full of dust. I put them in a shopping bag by the bikes. There was spider behind them I had to kill.”

Gerry took off his Dodgers cap and rubbed his forehead. He stared down at the carpet and made the whistling sound he made whenever he was trying to act like everything was okay. “Is that where the photos are too? In the garage?”

“What photos?”

“Don’t play dumb, Heike.” I knew which photos he meant: the photos of Fern sitting in front of the fireplace wearing a New Year’s hat, and Fern throwing a stick for Goldie at the beach, and Fern and Gerry with their sons, David and Rick, in front of Tomorrowland. The photo of everyone at Disneyland was my favorite. When we first moved to Gerry’s house, I looked at that photo a lot. I wondered whether Gerry and Fern were good parents and whether David and Rick were happy growing up. I remembered trying to figure out what David and Rick were like back then, before their mother died. I wondered whether they were into fantasy games, or volleyball and skateboarding. The few times I’d met them, they both seemed quiet. Not nerdy quiet, just distracted, like they wanted to be somewhere else. In the photo they both seemed well-adjusted though. They were smiling and holding hands with Mickey Mouse. Gerry was giving Rick a piggyback ride, and Fern had her arm around David. For some reason I always ended up wondering whether Fern already had cancer growing inside her when that photo was taken. I often wondered whether my mother might have cancer or something else wrong with her; I wondered who would take care of me if she died.

“Did it ever occur to you that those photos might be important to me?” Gerry continued. He spoke slowly, enunciating each word carefully, as if his tongue caused him great pain. Then he went out to the garage, got the shopping bags, and brought them inside. I stayed on the couch in the family room, but I wasn’t paying attention to the TV. I was waiting to see what Gerry would do. I was waiting to see whether Gerry would throw something at my mother and tell her to fuck off. That’s what my real father would have done. He would have told my mother not to touch his fucking things ever again. Instead, Gerry got a dishtowel from the kitchen and wiped the photos. He held each frame carefully and ran the towel over the surface of the glass.

“I’m sorry,” my mother finally said, starting to cry. “I shouldn’t have put them away. I just couldn’t stand it anymore, seeing Fern there every day, judging all the time from the grave.”

Standing in the living room, I could tell Goldie wanted me to pet her. She was looking up at me, wagging her partially bald tail. I decided that, instead of going back to check on my mother, I would scoop up Goldie’s droppings. It was the chore I hated most, the chore Gerry always had to remind me to do before I got my allowance. I opened the door to the yard, and Goldie followed me outside; even though she was old, she still liked to make her way over to the lemon trees and give them a sniff.

I walked to the grass with my plastic bag and the shovel, and I remember wanting to cry. The grass was brown, and some of the turds were so old that they looked like little pieces of wood. I retrieved the droppings with the utmost care, making the task last as long as possible. At one point, Goldie stood next to me, panting. Ten minutes later my mother and Sabine returned home.

“There you are,” my mother yelled. “How dare you leave us stranded there on our own. Did you see the police? We could have been imprisoned!”

I told her I’d tried to call Gerry but that he was busy, and I was waiting for him to call back. I showed her what a good job I’d done cleaning the lawn. Sabine, whose hair was still damp, kept saying she wanted to be driven back to the motel.

That evening, Gerry laid into my mother. “I’ve had it, Heike! I can’t live like this anymore!”

“How was I to know Carol would get home so early? We just went for a quick dip.”

“By the way,” I announced in the middle of their fight, “I’m not going to be here for dinner on Saturday.”

“What do you mean?” asked my mother.

“I’m just not. I’m not going to sit here in front of Jason and his sister and act like everything is normal. They probably think you’re a total retard.”

“How dare you!” She lunged toward me, but I was too fast. I ran into my room and locked the door.

“Open this door and apologize to me!” she screamed. “I am your mother!” The more she pounded, the louder I turned up the radio. I sat at my desk trying to concentrate until, eventually, I put on my shoes. I emptied everything out of my backpack, took my life savings — $56.23 — from the box I kept under my bed, and folded up three of my favorite T-shirts. I put the shirts in my backpack, along with the Dungeons & Dragons characters I’d painted by hand and a piece of turquoise my father had given to me as a present, and climbed out the window.

I moved fast, past house after house, afraid someone would catch me. When I reached the intersection at the top of the hill, I headed to Vons. I thought that, at a minimum, I’d need cereal for my trip. I walked to the aisle with the Fruit Loops and Lucky Charms and the other cereals my mother always said were too expensive, and as I studied the choices, I wondered whether I should have told Gerry and my mother where I was going. I imagined them pounding on my door, then picking the lock. I pictured my mother going berserk. I considered sneaking back to leave a note so she wouldn’t worry. I’ll be okay. I’m going to Mrs. Moy’s. Love, Stewart

Mrs. Moy was the woman who’d taught me Sunday school in Ventana Beach. She’d always told me that if I ever needed anything or if I was ever in trouble, I could give her a call. I didn’t know her address, but I knew her number by heart. I went up to the cashier, gave her a box of Frosted Flakes, and handed her a ten-dollar bill.

“Do you mind giving me my change in quarters?” I asked.

“You bet, sweetie. You going to Vegas?”

I smiled, not sure what she meant, then headed to one of the payphones, where I picked up the receiver and dialed Mrs. Moy’s number. An automated voice told me I needed to put in ninety-five cents for the first three minutes, and after I deposited the coins, I listened to the phone ring. I let the phone ring at least twenty times before I finally hung up.

I watched the people in the parking lot put bags of groceries into the trunks of their cars. I wondered whether my mom and Gerry were watching the ABC Thursday Night Movie, something about a woman who claimed her family was abducted by aliens. Eventually, I decided to walk to the beach. I’d walked to the ocean lots of times with my mother, and I remembered how each time we passed a particularly nice house, one of us would say that was the kind of home we wished we could live in. Some of the houses had elaborate gardens and pools and huge windows that allowed you to see into the living rooms and kitchens and dens. I thought about the children on the milk cartons. Every morning, when I was eating my Cheerios, I always stared at the black-and-white photo of whatever child was featured in that week’s advertisement. The caption was always the same — Missing Child — but the details were different:

Melinda Ramirez, Age 9. Last seen in El Cerrito Mall (June 23, 1975)

Peter Yates, Age 7. Last Seen at Pismo Beach (March 13, 1973)

When I arrived at the bike path along the edge of the beach, I headed toward the pier. Occasionally I saw someone go by on roller skates or a bike, but for the most part the beach was deserted. The air on the pier felt cooler than I expected, and below me I heard the sound of the water. I sat at the end of the pier, letting my legs dangle over the edge and studying the oil derricks in the distance. I kept looking at my watch, wondering whether my mother and Gerry had figured out I was gone. I wished I’d brought a jacket along, instead of just my sweatshirt, and I tried to keep my legs as still as possible so I wouldn’t get any splinters.

Eventually, a homeless guy with a sleeping bag and a fishing pole sat down on the pier and smiled at me. “How’s it going, buddy?” he said. His teeth were brown and crooked, and he wore a shaggy beard. There’d been stories in the news about a man who strangled women in the Hollywood Hills and about a retired dentist in Arcadia who kept a twelve-year-old girl locked up in his cellar for ninety-six days, until she finally escaped when he went to the movies. I imagined the principal of my school telling everyone at Friday’s assembly that my dismembered body had been found in a dumpster.

“What brings you out to these parts?” the drifter asked.

I pictured a hiding place under the pier where he forced people to have sex with him before he suffocated them. I wondered whether anyone would hear me if I screamed.

“Want a swig?” He offered me a bottle inside a paper bag.

I shook my head, looking down. My body felt light; suddenly I had to go to the bathroom. Without thinking, I leapt up, grabbed my backpack, and sprinted down the pier, toward the houses along the shore. I ran until I was sweating hard and my lungs felt raw and I reached a group of teenagers sitting on the strand smoking and laughing together. They looked at me and smiled, but I didn’t stop. I climbed the huge hill leading from the train tracks to Sepulveda in record time. I pictured my mother on the couch, holding her wooden spoon, waiting. I decided to tell her that I’d snuck out of the house in order to buy her a gift.

Finally, when Gerry’s house came into view, I saw that all of the lights were off except the one in my room. I hurried down the block and peered into my window. Miraculously, my room was exactly as I’d left it: the door was still locked, the folders and books I’d taken out of my backpack on the carpet next to my bed. I climbed back inside, my heart like a drum. A few minutes later, I turned out the light and got into bed. I held my breath, listening, but the house was perfectly quiet.

The next morning, when my alarm clock went off, I got dressed and went out to the living room like nothing had happened. “Thank you for saying goodnight,” my mother called from the kitchen. “That was very nice of you.”

I apologized, saying I’d fallen asleep while I was studying. “We don’t have any more apples,” she said, as she was making my lunch. “Is a banana okay? They’re a little brown.”

That afternoon, after I got home from school, I was in my room when Jason’s mom, Mrs. McFarland, called to say they’d come down with the flu. “Are you happy?” my mother hollered. “Your friend cancelled! They’re not coming over.”

During the following weeks, I went out of my way to avoid Jason. I changed my route to and from school, and I spent as little time as possible in the hallways between classes. I took solace in the fact that next year Jason would be going to Tres Caminos High. As for Sabine, my mother’s plan to have her move in never came to fruition. Two weeks after my mother and Sabine were almost arrested, as I was coming home from school, I saw my mother sweeping leaves in the driveway. She was wearing sunglasses, but I could tell she’d been crying. When I asked her how she was, she refused to look at me. “Fine,” she replied.

“What’s wrong?” I asked.

“Doesn’t matter.”

“What do you mean? What happened?”

“Nothing. Nothing happened.” She kept sweeping the leaves, and I stood there looking at her. Finally she said, “Sabine is moving to Ohio. She decided to move back East to be closer to her cousin.”

“Gosh. When did you find that out?”

“Little while ago.”

“Really?”

“Yes, really. Stop pretending like you care about me. I know you don’t give a damn.” My mother started sobbing. “I just can’t take it anymore.” She let the broom fall onto the driveway. “One of these days I move back to Germany.”

I tried to calm her down. I asked her to tell me what Sabine had said, and then she told me the story. She said that Sabine never agreed to let her give any of the cats away and that, when my mother told her what she had in mind, she flipped out. “She accused me of trying to steal these pets from her. I told her this was not the case at all, but she wouldn’t listen. I drove over there and tried to talk to her, but she was like a different person — so cold and icy. Her eyes were like rocks. Afterwards, I couldn’t even drive I was so upset. I had to pull over into a gas station.”

I stood under the huge willow tree outside Gerry’s house, looking at my mother, wondering whether I should give her a hug. I knew she wanted me to cry with her, to tell her I loved her and no matter what, I would always be there for her. I knew she wanted me to reassure her that it didn’t matter what Sandi Sarconi or Carol Wallace or Jason’s mother thought of her. But I couldn’t bring myself to say any of these things.

That December, amidst continuing news stories about Stockholm syndrome and the Symbionese Liberation Army, Hotel California hit the charts and Rocky and King Kong were released. The few times that I saw Jason over Christmas break, he was walking on the street with a girl who wore lots of lip gloss. By that point, I already knew that he’d climbed over the fence to retrieve his magazines. I’d gone out back one afternoon when my mother wasn’t home, and all I found amidst the thicket of lemon trees were a few torn pages with part of an article about trout fishing and some photos of a woman sitting on the hood of a green Porsche. The paper was wet and discolored, and when I shook the leaves and dirt from the pages, a pill bug fell to the ground.

I brushed the dirt off the paper as carefully as possible and folded the pages. I surveyed the area to make sure I hadn’t accidentally missed any remnants of the other magazines, then crept out of the tangle of branches and went back to my room. I closed my door, spreading the pages out on top of my desk and examining them, as if I were looking for some kind of clue. I knew that soon enough my mother would come home and start making dinner and that she would expect me to peel potatoes or make fruit salad or stir something on the stove so she would have someone to talk to.