interviews

Unsettling Things, an interview with Amelia Gray, author of Gutshot

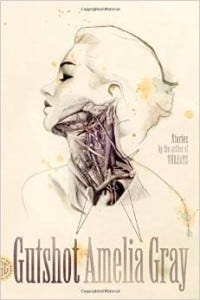

Alice Munro says that a story is not a road to follow, but more like a house to explore, with corridors to wander and windows to look out of. If this is the case, the reader who enters the stories in Amelia Gray’s latest collection Gutshot (out now from FSG) is sure to come away thinking no one builds houses quite like hers. They are houses in which all manner of foreign and unsettling things are happening, inhabited by characters that feel artfully bent away from the ordinary and yet wholly recognizable. The houses are sturdy, except when Gray wants you to hear the foundation creaking. They feel safe, until she wants to remind you that no house ever is.

And when Amelia Gray builds a house, she more than satisfies Munro’s wish that the house be “built out of its own necessity, not just to shelter or beguile you.”

Vincent Scarpa: Why not begin with beginnings? One of the things I admire so much about your stories are the unforgettable and distinctly Amelia Gray ways we enter them. I can’t think of another writer whose stories invite the reader in quite like yours, be it by way of introducing a distillation of the story’s strange or otherworldly conceit — I’m thinking here of a story like “A Contest,” which begins, “The gods decided that, once a year, they would have a weeklong contest and allow the one person who felt the most grief over the loss of a loved one to have that loved one return,” — or a deceivingly simple opening line that gives no hint of the deep strangeness we’re about to encounter, as in “House Heart,” one of the highlights of the collection and one of its most disturbing and unsettling stories, which begins, simply, “The home remains.” I’d love to hear you talk about opening sentences: what you see as their possibilities or responsibilities, and how they open up the drafting process for you in writing.

Amelia Gray: Lately I like a straightforward opening line. When I was first thinking about “A Contest,” I was feeling overwhelmed with death and I thought to myself, What if there was a point to grief like this? What if there was some kind of contest? And then it was a matter of figuring out the best and most efficient way to say that in a way that conveyed the information in kind of an invisible way. It got me thinking about the gods, maybe three or four guys, no more than would fit into a helicopter. I just double checked my first draft of “House Heart” and it has that first line still. I don’t always start with a first line set like that. “House Proud” at the end of the collection went through many different iterations and actually took its first paragraph from a standalone piece I’d written at a different time.

VS: The stories in Gutshot that are operating in otherworldly ways never fall back on the innovativeness or unique strangeness of their premises. They don’t rest on the laurels of their own cleverness. I think of a writer like Aimee Bender — and there are plenty of Aimee Bender stories I truly love, to be sure — but for me she sometimes get trapped under the weight of her conceits. When working with these kinds of stories, how does one — how do you — go about catapulting them past their shiny mechanics, imbuing them with a deeply-felt sense of humanness? How do you bend them into something beyond inventiveness?

AG: Ah, it doesn’t always work for me either. Sometimes a story is just larger or smaller than what I’d like it to be. Lately I’ve been thinking about this. I love writing fiction on assignment and with a prompt in mind, a series of constraints, but it sometimes doesn’t go well when I’m told I need to make a certain word count. I’ll write a story about haunted tree stumps all day long but when you say it has to be five thousand words, the character is going to change from what might be its ideal form.

VS: I’m wondering how you feel about your work being characterized as “eccentric.” It’s not inaccurate, I suppose, but it feels incomplete. It feels reductive. It doesn’t account for what you manage to do so beautifully with what is familiar, what we might think of as banal. There are no shortage of stories about falling-apart relationships, but your couple in “These Are The Fables” is so precisely rendered and nuanced, their present circumstances so weighted, the dialogue so masterful and hysterical and upsetting, that no sane reader would come away from that story thinking they’d read just another falling-apart relationship story. And that isn’t eccentricity, it’s a keen insight into the human condition. It’s your finger on the pulse of fragility. I don’t know, maybe I’m just defending you against a term — employed in praise, no less! — that doesn’t bother you in the slightest.

AG: When I think of “eccentric” I picture myself forty years in the future draped in purple velvet and carrying a parasol, which seems right. Surrounded by cats. I’ve been very grateful and happy to do interviews around Gutshot, but talking about the book this week has been a bit like spending life with a hand-mirror. But to your larger point, I don’t mind “strange” or “eccentric” or similar. I used to dislike “clever” or “ambitious” because I found it a little patronizing, but mostly I just don’t read reviews very much because I find they get into my head. I feel like I’ve been lucky to have some very thoughtful reviews for Gutshot, and even when the reviewer is squeamish, they’ve dug deeper, like they’re the ones with the hand-mirror or maybe the parasol.

VS: I want to ask you about structure. The stories in Gutshot are organized into five discrete parts, and I’m curious how much of that organization was present in your original manuscript and how much was the product of editorial work. The groupings feel extremely purposeful, meaning-making. There’s a ringing, a resonance, a note being sustained through each section that I probably couldn’t name or nominate but felt was undeniably at work, and I found this a really instructive way to experience the collection as a whole.

AG: I wrote the collection over the course of six years and through that time, I found myself naturally interested in different things. For a while I wanted to collect a group of stories based on logical fallacies, which never worked out really, and then I wanted to write a collection where each story responded to kind of a philosophical posit, and then later I was writing fables, and love stories. Some of it was mixed into other bits and none of it was very purposeful, but when I had finished the collection I printed it all out and physically moved stories around in my bedroom until I found that five parts emerged. It came out of feeling personally overwhelmed by 38 short stories and wanting to group into portions of resonance. So I’m glad to hear it rang true with you.

VS: One of those unanswerable, useless questions I often hear posed from a well-meaning audience member at a reading is, “Where do you come up with your ideas?” And yet it’s also a perfectly legitimate and understandable reaction, when reading the stories in Gutshot, to wonder how you’ve landed where you have. You read a story like “House Heart” and think, How the fuck did this come to be? So, in lieu of asking how you come up with your ideas, what I’ll ask instead is this: How do you decide which ideas are worth following and which aren’t? Do you do much story-abandoning?

AG: Yes, I do abandon a lot of stories! Sometimes they are written and they become abandoned, or sometimes I think only of the idea and move on. Last night, I was picturing two people giving a third person increasingly bad romantic advice at a bar, and then wondering if it wouldn’t be better for the dramatics of the story if these people were simply living their own bad love advice rather than presenting it to someone else — for example, a man gives a woman the flu so he can be the one to nurse her back to health. There’s something pretty good there but it’s not quite a strong enough concept. So I’ll keep thinking about it, and maybe I’ll try writing it in a couple weeks if it’s still bouncing around up there.

VS: Who are the writers whose work interests and engages you? Are there any books or stories or poems or essays you return to over and over?

AG: I was just re-reading Shirley Jackson. Nabokov, James Joyce, Vanessa Place, Joyce Carol Oates. I want to re-read Anna Karenina and The Inferno. I have a big list of things I need to read and think about. It’s so good and exciting to be a member of a living community like the writing world but it means a lot of reading! I’m envious of the average New Yorker’s commute.

VS: What are you working on now?

AG: I’m working on a novel right now, about pride and art and loss and stubborn love. It’s a historical fiction and I’ve been working on it for three years.