interviews

Victor LaValle talks monsters, myths, and a Grand Unified Theory of Fear

While listening to Victor LaValle read a short piece on trick-or-treating in Queens, I was transported back to the Halloween nights in Washington Heights when the working class kids from my tenement headed to the building across the street — where the gentrifying middle class families and good candy were — and smashed our fists into the buzzers until someone let us into the building.

Victor LaValle grew up in Queens, New York and is the author of one story collection and three novels. His most recent novel, The Devil in Silver — a horror story set in a New York City mental hospital — was a New York Times Notable Book of 2012. He has been the recipient of numerous awards including a Guggenheim Fellowship, an American Book Award, and the Key to Southeast Queens. He teaches creative writing in Columbia University’s MFA program.

I asked LaValle about his horror obsessions, what he feared as a kid growing up in the bad old days of New York City, and what he’s going to do when the monsters come.

Adalena Kavanagh: After hearing you read a story about celebrating Halloween night I felt a kinship with you because it sounded like we both grew up in similar New York City neighborhoods. Where did you grow up in Queens? What were your neighborhood bogeymen? I grew up in Washington Heights and didn’t leave until 2009 so I saw the whole arc of the crack epidemic and later gentrification. Growing up in a “rough” neighborhood you’re taught to be careful or street smart and thinking back my bogey men were crack heads, drug dealers, the police and sexual perverts. Though I grew up near crime, in a city known for crime, I’m probably most spooked out in the country where it’s too quiet and nothing is likely to happen. I like to say that when the sun sets, the wind chime becomes the soundtrack to your murder.

What were you scared of when you were a kid? What are you scared of now? How do you think living near crime affects your perception of fear and danger?

Victor LaValle: I grew up in Queens in the late seventies and early eighties. I lived in Jackson Heights and Flushing, neighborhoods that really weren’t too bad or at least didn’t seem bad to me. I think I’d only get perspective on the place, on the city as a whole, when family friends visited from places like Maryland or Virginia. In a way their fear communicated to me the idea that there was anything to fear. Before that I mostly thought of my neighborhoods like, I’m guessing, almost anyone does: home. And the things to deal with were just the things to deal with. I’d totally agree that nothing spooked me more than the idea of the countryside. I read a lot of Stephen King, H. P. Lovecraft, Shirley Jackson and there were all bad advertisements for life outside of cities. All the bad shit happens in the small towns and rural areas. They get otherworldly monsters and demons and whole towns that stone poor girls to death. My biggest childhood fear, really, was just getting beat up by older boys. That’s pure cake comparatively.

All the bad shit happens in the small towns and rural areas. They get otherworldly monsters and demons and whole towns that stone poor girls to death.

I will admit though that at a certain age I became more aware of the idea that New York City, as a whole, was dangerous. I was probably ten or so. But my concerns weren’t really about me they were about my mother. There were two movies I remember seeing that caused my fear. The first was a terrible made-for-TV movie based on the Guardian Angels. The other is this terrifically bad movie called Fighting Back from 1982. It starred Tom Skerritt, it’s just a Death Wish rip-off, but there’s this one scene that I just shouldn’t have scene when I was that age. And it left me afraid the same thing was going to happen to my mother. The whole clip is silly, but the rough part comes about 2:15. It really gave me a shock. This movie took place in Philly but I felt it was a fine picture of the anxiety running through the “gritty” New York of the era, too.

AK: At first I thought that I wasn’t well versed in horror, but that’s mostly because I don’t like the gory type of stuff like the Saw movies. But I think at the heart of it, the monsters in horror or the supernatural are symbolic manifestations of our psychological fears. What do you think horror is? What draws you to horror?

VL: There’s a certain definition for the word monster that I love. It derives, in part from the Latin word monstrum, and can be translated as an omen or a message from the divine. To me this comes closest to explaining the appeal of horror, at least for me. All the best horror, the best monsters, terrify in their embodied state but also in the idea of what they represent. They have to do both. That’s why, for me, something like a dragon doesn’t qualify as horror. It’s fantasy not because it’s unreal (so are Dracula and Jason Voorhees), but the dragon doesn’t speak to any kind of idea or wisdom that causes me to tremble. The dragon doesn’t seem like a message from the divine, it’s just a really big lizard. (Though of course Godzilla does seem like a message, but of course he’s a dinosaur not a dragon.)

In a way I’d say our psychological fears then are actually manifestations of far older wisdom and not the other way round, from long before the idea of the human psyche became codified. I like the idea that part of what terrifies us is the feeling that there’s a world far past what our own minds can come up with. Certainly there are fears we generate but even these, potentially, can be tamed. More frightening is the sense that there are things we can’t tame, can’t even reckon with, and so we tell horror stories to try and reconcile this fact.

AK: I’m most drawn to psychological suspense and the supernatural. I love Shirley Jackson and one of her scariest stories is “The Summer People.” She’s a master of suspense but she might not be the first person that comes to mind because she grounds her suspense in the horrors of the domestic. What are your favorite horror movies, and books? Why?

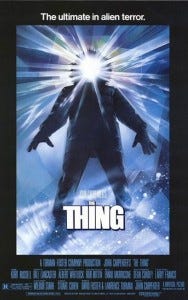

VL: My favorite horror movie — both because of its quality and because of when I first saw it — is without a doubt John Carpenter’s The Thing. I have a vague recollection that I saw it on TV but I’m completely sure that’s wrong. The gore alone would’ve made that impossible in the 1983 or 1984. But I do remember watching it on a TV which must mean someone had it on VHS. Most likely this was one my childhood best friends, Glenn Roth, whose father was a source of horror movies, HBO semi-porn flicks, and actual porn flicks. (He didn’t know he was our source, but that’s beside the point.) Here’s a clip of John Carpenter talking about how and why he made his version and why his monster is simply one of the best ever brought to the screen. (Considering that almost all movie monsters suck terribly once you see them.)

I love this movie for many reasons, but most of all the “moral” of the story was, in the end, about self-sacrifice. At least that’s how I saw it, even as a 13 year old kid. By the end the film becomes a kind of debate about the drive to live no matter the cost versus the willingness to die so that others might live. I’d really never seen a movie tackle this issue and I haven’t seen many do it since. The fact that it did so while showing a man’s head crawl away from its body on legs that sprouted from its scalp was really just gravy.

That said, and on entirely different chord, I’d count Robert Altman’s 3 Women as another brilliant horror movie. Haunting and dream-like, this movie just straight up baffled me the first time I watched it. It still does, but I’ve watched a half-dozen times since.

AK: I’m obsessed with the psychologically unreliable narrator or narrative (think of all the characters in Shirley Jackson’s The Haunting of Hill House) and the supernatural, particularly Chinese ghosts and spirits, Daoist shaman, and Daoist exorcisms. What are some of your horror related obsessions?

VL: Being raised a Christian, I think my initial feelings/reaction to the supernatural were undoubtedly filtered through that lens. Good and evil, the Devil versus the Lord. But in a way this filter demanded that I not actually be all that conversant with the Bible in order to think of it that way. To actually read that book is to confront the confounding, conflicted nature of both the Hebrew Bible and the New Testament and to marvel at the ways that book is more of anthology of many old faiths from the Middle East, incorporating the old gods and demons in order to assimilate them. Once I began to understand my tradition in this light it was easier to sort of leaf backward to Babylonian myths, which were no doubt once Babylonian religious doctrine, Sumerian and all the rest.

And yet it’s not, strictly speaking, my tradition. What I mean is that my Ugandan mother (and even more so my grandmother) were devout Episcopalians because the British ruled Uganda and brought their faith with them. Unlike many other parts of the world, Ugandans didn’t hide their old faiths inside the new one. Most of them cast off the old ways and took on the new and the nation is still overwhelmingly Christian. Weirdly, it’s that absence before Christianity that also interests me. Like a phantom limb of faith. As a result I find myself interested in the idea that there’s a face behind the face, a god behind the gods. Maybe this is just my way of saying that gods or demons or ghosts or werewolves all seem like versions of a newer faith that’s taken place of the older one and that older one, in a sense, is defined by its emptiness. Is this getting foolishly esoteric? I like to think there’s a Master Key to reality, a Grand Unified Theory of Fear. At least some of my reading, and a lot of my writing, is an attempt to track it down. I can’t think of a better way to segue into a Black Sabbath song than that.

AK: “More frightening is the sense that there are things we can’t tame, can’t even reckon with, and so we tell horror stories to try and reconcile this fact.” How does writing horror relieve us of our fears or provide comfort? Is it like the vaccine that’s made from the thing that will make you sick?

VL: I feel like it’s just a pressure release valve, one that not everybody needs or even welcomes. The same way, I guess, that not everyone finds roller coaster rides thrilling. The old, but I think true, take on horror is that it lets us feel the fear without risking true pain. The part I find most interesting is that so many of us need to feel that fear. I think it’s because we understand, on various levels, that existence can be tremendously difficult and downright horrifying. Literature and film and art that acknowledges this fact confirms the feeling and that confirmation alone can be a gift.

AK: In horror movies there’s always a moment where you’re shouting at the screen, “Get out! Get out!” I’d like to think that I’d stay and fight, but I’d probably only do so if the monster, demon, or whatever was about to get my mom, sister, or niece. Anyone else, I’d probably run or just lie down and die. What are you going to do when the monsters come? Are you going to fight? Why?

VL: One of the things I hate most about the modern horror film/television is that neither seems to take into account the sophistication of its audience. I recently reread a story by the wonderfully named Oliver Onions called “The Beckoning Fair One.” (This is a link to an ebook download of the collection from which it comes Widdershins) This story has every now hokey horror movie cliche, even the cat that jumps out from nowhere for a cheap thrill. The story was published in 1911! In other words most horror movie makers haven’t updated their shit in over one hundred years.

In other words most horror movie makers haven’t updated their shit in over one hundred years.

I bring all that up to say that I think it’s an artificial device to have the people stay and fight. Nobody with an ounce of sense would. People get angry when people shout “Get out!” at the screen, but they are doing this because they are protesting an insult to the audience’s collective intelligence. I’d say it was a courageous move to high tail it out of there because if you were faced with a monster or demon your entire understanding of the known universe would have to suddenly be thrown into question! When the monsters come I’m going to open my third eye and obliterate them with my ultra-wisdom beam because if they’re real then my magic will be too.

AK: There’s this idea that horror movies are actually meant to maintain the status quo. That this is why women and people of color suffer the most in horror films. What do you think?

VL: Horror and porn both work to reveal the hidden urges of a society. This isn’t the fault of the genres though, it’s the fault of the people who create them. One of the reasons I’d love to see more women and people of color making films is just so we’d get a much broader spectrum of bizarre, and deeply biased, perspectives on screen. The only thing I really object to is blatant stupidity. Take, for instance, this opening scene from Jurassic Park.

A no doubt multi-billion dollar enterprise has built an island paradise/dinosaur park (not to mention brought dinosaurs back to life) but they haven’t created a cage with a door that can rise automatically? And then, amongst the all-white team helping to get the raptor loaded, the guy who must raise the gate manually is black? Get the fuck out of here. Again, this isn’t the fault of the genre (science fiction) this is the fault of a series of guys — from the director on down — who thought nothing of not only the scene but the life sacrificed. That’s a bigger problem than a genre.

AK: “Once I began to understand my tradition in this light it was easier to sort of leaf backward to Babylonian myths, which were no doubt once Babylonian religious doctrine, Sumerian and all the rest.”

It’s so interesting to me to think about mythology because the way we study myths today we look at them as these superstitious stories but you’re probably right in that at one time they were religious doctrine. Why do you think horror writers or movie makers reach back to archaic religious practice to hang their stories on?

VL: There needs to be a certain amount of distance from a practice or a belief before it can be turned into entertainment. The Da Vinci Code was an event, in part, because it turned a fairly recent and world-dominating faith into mere fodder for a romp. Some people protested I guess, but not enough to suggest it was “too soon.” But the farther back you go the more readers and viewers are willing to buy into all kinds of supernatural stuff they’d scoff at if based on things now.

Many of the Gothic novels of the 18th century are actually set hundreds of years earlier. This was because those authors also knew that human beings are more willing to enjoy a book about the superstitious past rather than the superstitious present, especially if our modern day superstitions have yet be disproven, even the scientific ones. (String theory, I’m looking at you.)

human beings are more willing to enjoy a book about the superstitious past rather than the superstitious present, especially if our modern day superstitions have yet be disproven, even the scientific ones. (String theory, I’m looking at you.)

AK: “Weirdly, it’s that absence before Christianity that also interests me. Like a phantom limb of faith As a result I find myself interested in the idea that there’s a face behind the face, a god behind the gods. Maybe this is just my way of saying that gods or demons or ghosts or werewolves all seem like versions of a newer faith that’s taken place of the older one and that older one, in a sense, is defined by its emptiness.”

Monsters are scary until you kill them, but what seems scarier is that emptiness you talk about here. What are some of your favorite examples of the faceless monster, or the scary thing that cannot be seen or named?

VL: The greatest “emptiness” monster from my childhood comes straight out of The NeverEnding Story. The Nothing!

“Who are you really?”

“I am the servant of the power behind the Nothing.”

That’s great horror. My only issue with the Gmork’s explanation is that he labels the Nothing as despair, but this strikes me as still too optimistic. There is a God and it’s not there. To me that’s terrifying to contemplate. By comparison, even H. P. Lovecraft’s Old Gods mythos is too optimistic. After all Cthulu is there in a coma (or something) at the bottom of the South Pacific. Even Lovecraft still wanted to be able to point, in some general direction, at something.

AK: What are some examples of a Grand Unified Theory of Fear? Or if not that, what are the elements you’re looking for in a great horror story or movie?

VL: I do like the stuff that makes you come away thinking a bit. Whether you’re thinking about what happened in the story or about its grander implications doesn’t really matter to me but I don’t want to be entertained alone. Believe me, entertainment is hard enough but the best stuff offers more. Even if I disagree with the idea or the philosophy at the heart of book or a movie I want to feel as if there was a philosophy in play. Be interesting, I suppose that’s the only thing I’m asking. And that’s the case for book, movies, music, and people.