Books & Culture

Wanderings: On Mary McCarthy’s “A Guide to Exiles, Expatriates, and Internal Émigrés”

“In early use an exile was a banished man, a wanderer or roamer: exul.”

As I stroll under a canopy of trees on a wide clean path that leads to the rocky shores of the Trail of Tears river crossing in Chattanooga, I listen for the Native American ghosts, exiled. I want to hear the wind wail. I want to hear the leaves crying. I want to be haunted by their eternal longing for home.

The exile waits to return, sometimes forever. McCarthy writes, “This condition of waiting means that the exile’s whole being is concentrated on the land he left behind, in memories and hopes.” Yet, for the Cherokee tribes forced onto the Trail of Tears from Ross’ Landing in Chattanooga in 1838, there is no “there” to return to, for their home has been erased.

“But in recent times it is worth noticing, a new word, ‘refugee’ describes a person fleeing from persecution because of his category.”

These are some of Chattanooga’s refugees: an elderly Cuban man I drive to the clinic because his knee hurts and his blood pressure is high; a young woman from Columbia, hair still wet from her shower, I drive to the woman’s clinic for her annual exam, a silent woman from Somalia, buried in layers of sweaters and scarves, who looks as if she is sixty, but whose refugee card states her date of birth as five years before mine; an ambitious Iraqi Kurd, who I drive to take his GED so he can begin college classes; another young man, a Sudanese, who wants to resume his career as a pharmacist.

These refugees have one thing in common: they fled their countries because their lives were in danger.

“The exile is a singular, whereas refugees tend to be thought of in mass.”

The artist as exile represents a significant contribution to the Western literary canon, starting with Dante and Ovid and continuing with writers such as Vladimir Nabokov, Herta Muller, Milan Kundera, and James Baldwin. In Portrait of an Artist as a Young Man, James Joyce writes that the three conditions for an artist are “silence, exile, and cunning.” Joyce himself chose a self-imposed exile from Ireland because he believed his own country would stifle his work.

Joyce himself chose a self-imposed exile from Ireland because he believed his own country would stifle his work.

Czeslaw Milosz, the Nobel Prize winning poet, considers the personal exile of an artist like himself, who emigrated from Poland to the US in 1960. In his essay, “Notes on Exile,” he writes, “Exile accepted as destiny, in the way we accept an incurable illness, should help us see through our self-delusions.” In this sense, exile is a type of destiny, because one’s personal life is dependent on larger historical forces. Yet, being separated from one’s culture presents its own problems. As Milosz says, “Now where he lives he is free to speak but nobody listens, and moreover, he forgot what he had to say.”

“An expatriate is almost the reverse. His main aim is never to go back to his native land, or failing that, to stay away as long as possible. His departure is wholly voluntary.”

In contrast to exiles who are unwillingly separated from their culture, expatriates often want to flee theirs. Now more than forty years after McCarthy’s 1972 essay was published, the term expatriate sounds distastefully antiquated and colonialist. Today, as people voluntarily between and among countries and whose values connect them to ways of living rather than nation states’ terms more often call themselves transnationals, global citizens, and third cultures than expatriates. Even in the 1960s, Baldwin, who spent much of his adult life in France, referred to himself not as an expatriate or an exile, but a “transatlantic commuter.”

Today, as people voluntarily between and among countries and whose values connect them to ways of living rather than nation states’ terms more often call themselves transnationals, global citizens, and third cultures than expatriates.

When I moved to South Korea in 1995, I half-consciously had some romantic notions of being an expatriate writer living in self-imposed exile in order to write. My plan to live there for a year turned into twelve, and this changed the course of my life in ways I could not have imagined. Before I moved to South Korea, I was 31, married, and working as a technical writer, living in Arlington, Virginia with my husband, who had a solid job at Georgetown Library. Life was good enough, and our next logical moves were to buy a house and have a child or two and raise a family. The problem was, I’d grown up in Fairfax, Virginia, and hated these very suburbs I was about to commit my future to. For many people, the suburbs are a place of comfort, stability, and, if they are lucky, community. I found them stifling, alienating, and oppressive. If I’d kept my respectable job and bought a house in the suburbs, I’m sure my feelings would not have diminished. I would have lived one of those lives of Thoreau’s “quiet desperation.” I felt that quiet desperation already beginning to fall on me, heavy and inevitable. Only some radical changes — our decision to not have children and to live abroad instead — threw me off that looming trajectory.

That first year in Daegu, South Korea, was not one of glorious expatriation or creativity. The Confucian culture was too different from mine, and I missed many material comforts of home, which seemed superficial but were so much a part of my life: live music and art museums and decent wine and cheese. Popcorn. Before I left for South Korea, I was taking advantage of the cultural benefits of living in the DC area. For the two years before we moved to Korea, I was at one Smithsonian museum or another almost every weekend, catching a new art opening or historical exhibit. I went to Ethiopian restaurants and French bistros and coffee-shop/bookstores and drank microbrews. I went to wine tastings and outdoor concerts and dive bars and music clubs that no longer exist.

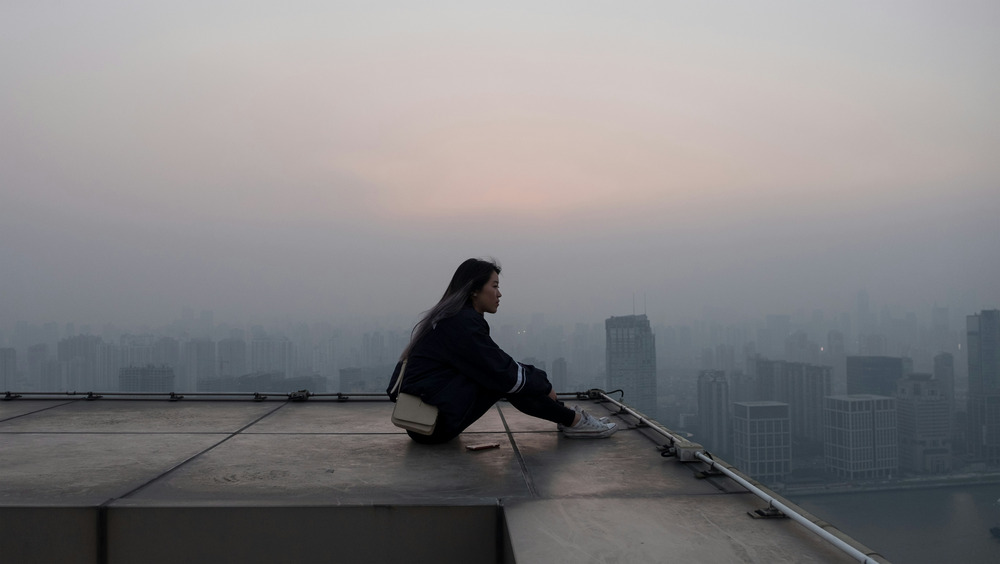

That life disappeared when I moved to South Korea in 1995. Instead, I ate Korean food and tried to teach a difficult language to a people who had just emerged from decades of poverty and dictatorship. I drank instant coffee and watched bad Hollywood movies on our VCR and drank watery beer and listened to the same music from a dozen CDs and mixed tapes. I searched for beauty and rarely found it that first year — I saw dirt and concrete and shorn trees and shabbiness. I smelled sewage and kimchi and garlic thick in summer heat. I did not love Korea, and I reluctantly missed home.

I searched for beauty and rarely found it that first year — I saw dirt and concrete and shorn trees and shabbiness.

That first year was long and exhausting, and I counted the days until we could return to the States. But then, a fellow American suggested I apply for a university job in Korea. I would work fewer hours, get more pay, and have long paid vacations in the summer and winter. I would have time to write and travel, things I wouldn’t have if I began working again in the States. I got a job at a university in Ansan, and my husband and I agreed to stick it out for another year.

After that first year, I took a few trips around Korea and in Asia, and I began to see the beauty I’d looked for that had always been in front of me. Persimmons growing on trees, flames of red leaves lining the streets, the traditional songs like some kind of ancient blues, the serenity of the temples, the smell of meat grilling, of incense. The wonder of walking to work, of getting around a country without a car. And when I went back to the States to visit, I saw some of the ugliness there — the myopic, insular conversations, the solipsism, the commercials on TV aimed at every kind of imagined ailment begging viewers to call their doctor and ask if brand x is right for you. I saw the larger and larger houses and wondered why people would want to live in them. I saw everyone driving into work, chained to desultory desk jobs.

I began to see the beauty I’d looked for that had always been in front of me.

The US was a country with faults, like many others. It was not the best place to live in the world, nor the worst. I loved my visits, but I was happy to get back to my two-room apartment with its heated floors and ovenless kitchen and my earnest, sweet students. Even more, I was eager for my next month-long trip to Mongolia or Burma or Indonesia.

One of Chattanooga’s most famous expatriates in exile is Bessie Smith, who left Chattanooga to join a showbiz troop as a singer in 1912, and never looked back. Just as Baldwin had to leave America to thrive, Smith, who lived in poverty in segregated Chattanooga, had to leave the small, restrictive town to become one of the most revered (and wealthiest) blues singers of all time. In some ways Smith helped Baldwin finish Go Tell It On The Mountain, which he wrote as an expatriate in exile. In a Paris Review interview, Baldwin says of writing the novel,

After ten years of carrying that book around, I finally finished it in Switzerland in three months. I remember playing Bessie Smith all the time while I was in the mountains, and playing her till I fell asleep.

For writers like Baldwin, a gay African American in post-World War II America, leaving or staying in the US was to him choosing between life and death. After he witnessed his friends either going to jail or committing suicide, Baldwin realized he could not become “a man” if he stayed.

In my case, I think my exile saved my life, for it inexorably confirmed something which Americans appear to have great difficulty accepting. Which is, simply, this: a man is not a man until he is able and willing to accept his own vision of the world, no matter how radically this vision departs from others.

Leaving the States did not save my life as it did Baldwin’s, but in a way it gave me one. I guess I should consider my twelve years in Korea as more of a time of voluntary expatriation rather than chosen exile. I was not escaping anything specific, but felt more that I was running toward something — a larger way of seeing the world and myself. Not so much a place, but toward a space that allowed me to expand my own vision, as a writer and as a human. What living abroad did for me was allow me to live as an outsider and to see the world, forever, in broader terms. It saved me from despair.