interviews

War Is Beautiful: An Interview With David Shields

David Shields is the author of international bestsellers and critically acclaimed books, including The Thing About Life Is That One Day You’ll Be Dead (Knopf 2008), Black Planet (Three Rivers Press 2009), and Reality Hunger: A Manifesto (Knopf 2010), which argued for the obliteration of the distinction between fiction and nonfiction, the overturning of laws regarding appropriation, and the creation of new forms for a new century. Over the past several years, Shields’s work has become increasingly political.

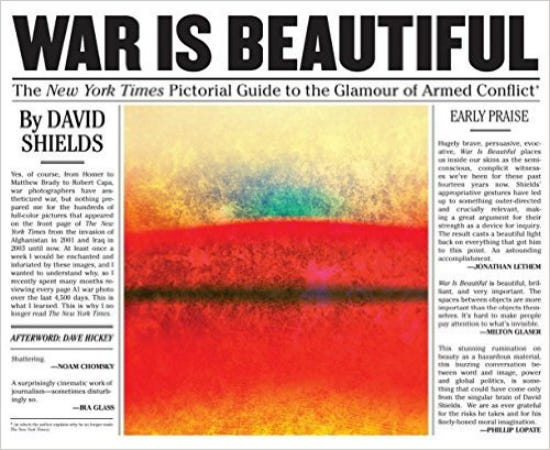

Earlier this month, I sat down with Shields to interview him about his new book, War Is Beautiful: The New York Times Pictorial Guide to the Glamour of Armed Conflict (powerHouse Books 2015). During our conversation, Shields spoke about the New York Times’s use of sanitized, sensually inviting front-page photography to glamorize the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq; these photos — in Shields’s view — desensitize readers to the cruelty and violence of these wars.

Rita Banerjee: The images of war in the book are very provocative. For example, in the Nature section, in the photo where you’re looking at a beautiful field of flowers and then you see the helmet of a soldier, it’s shocking. It grabs you. And even in the “Paintings” section, many of the images are so aesthetically inviting.

David Shields: They look like Abstract Expressionist paintings. They might as well have been painted by Rothko or Pollock.

RB: Reading War is Beautiful, you realize how cleaned up American media is. It’s weirdly Puritan, weirdly sanitized.

DS: It’s quite striking how this process happened over the last couple of decades. First of all, the rise of digital culture so that a picture could be sent instantaneously from the battlefield to the Times. Second of all, the advent of color photography on page A1 (starting in October 1997).

In the book’s afterword, Dave Hickey points out how serious and great war photography was from Mathew Brady in the Civil War all the way through Robert Capa during World War II and, say, Tim Page in Vietnam. And basically what happened during World War II was the rise of something he calls the “swipe photograph” — the quick photograph that conveys a quick, blurry image; for example, Capa, with his famous picture of a fallen Spanish soldier during the Spanish Civil War. And then what Hickey argues is that with the rise of Abstract Expressionism, people like Diebenkorn, Rothko, Pollock, Gerhard Richter, the swipe image became a huge part of Abstract Expressionism. And now war photographs are not based on what the war photographer is actually seeing in war. Rather, he or she is trying to reproduce Abstract Expressionist tropes — swipe-image gorgeousness.

All of these pictures from the New York Times are remarkably hollow and bloodless, composed, and abstract. All of these photographs have come, to a staggering degree, from art history.

…they’re looking for perfect composition; there’s nothing of lived life in these pictures…

These pictures are beautiful but dead, all 64 pictures (and I have 700 more cached that I could have used, though we couldn’t print all 700, of course; they are basically dead because, I would argue (as does Dave Hickey) that the photo editors, the photographers, page designers at the Times have all gone to school over the last fifty years on Abstract Expressionism and art movements afterward (photo realism, neo-realism, Pop Art). And so they’re looking for perfect composition; there’s nothing of lived life in these pictures, there’s only stylized —

RB: Framing, posturing.

DS: These pictures belong in an art gallery. They don’t belong on a front page of a newspaper, covering a war that’s created hundreds of thousands of civilian and soldier deaths. This is how war gets sold: war is portrayed not as hell but as heck, or even as heaven.

RB: I was really struck by your commentary in the beginning of War Is Beautiful. You raise the point, Is the Times complicit in selling a certain kind of narrative to the United States? That is, the Times promotes its institutional power as a protector or curator of a death-dealing democracy. Who is responsible for it? We all are. We are all inscribed in that death-dealing democracy.

Maybe that’s why we’re so accepting of capitalism as well. We don’t see the devastation. If people are dying of chemical poisoning in an Apple factory in China, how much do we care? The same with Iraq or Afghanistan. As Americans, we’re so used to the idea of distance. When the political world is distant from us, not only are we desensitized and numb to it but it’s almost as if we’re watching cinema or playing in a video game; there’s even a certain aspect of pleasure in a weird way. We have power and yet we’re at such a great distance from what’s going on and what’s going down.

Capitalism, distance, aesthetic pleasure, drone voyeurism are all part of one complicated cocktail.

DS: I try to make this emphatically clear via the book’s opening epigraph from Edmund Burke: “When danger or pain press too nearly, they are incapable of giving any delight, and are simply terrible; but at certain distances and with certain modifications, they may be, and they are delightful, as we every day experience. The cause of this I shall endeavour to investigate further.” Capitalism, distance, aesthetic pleasure, drone voyeurism are all part of one complicated cocktail. You’ve summarized it very well; it’s clearly capital that’s driving all this. We take pleasure in the privileged distance that capitalism buys.

RB: When examining the front page of the Times, did you encounter images that were slightly unframed or perhaps out-of-focus or hurried or not composed? All of these images, whether in the section “Beauty” or elsewhere, look like complete portraits, or they look like stills from a video game or movie. It begs the question, Is this war? Is this Hollywood? Does it matter?

DS: I know. That one photo: one chair and several water bottles, with gorgeous colors bouncing into the ether. [laughs] What is that?

RB: I wrote next to that image, “Almost innocent.”

DS: Because what does that have to do with — ? Why is that the front page of — ?

RB: Well, you know, David, by the time I got up to that image, I was thinking to myself, if you took out the New York Times from the text, or even the word “war” and you put it in a gallery and just did this as an art installation, how would people react? Would they even realize these are war images or would they not? They may not. If you decontextualize the imagery, I think some people might even buy a postcard of some of these images. Like the one with the piano.

DS: That’s an excellent, alternative, and even more depressing version of the book.

RB: You could just sell this as a postcard book.

DS: We have to admit that the pictures are beautiful, aren’t they?

RB: They are. I was thinking to myself, as I was looking at some of these images, if I didn’t know that this was about Afghanistan or Iraq, unless there was someone like Bush in the picture, I don’t know if I would find them viscerally shocking. I would probably think, “Oh, what a great shot,” “What great lighting,” or “What great color and composition.”

DS: That’s one of the main ironies of the book.

RB: So you don’t read the New York Times anymore, right?

DS: No.

RB: Really?

DS: After writing Black Planet and becoming very aware of the ways in which sports fandom operates, I could no longer keep being a fan of the games; it seemed too weird, too sad, too wrong. And so, too, having looked at 9,000 photographs on the front page of The Times over twenty years, I just found myself incapable of continuing. Occasionally, someone will send me a link to an article.

RB: I think I do that sometimes. Sorry! [laughs] I’ll try not to do that.

DS: I definitely don’t subscribe to it, either digitally or physically.

RB: I actually don’t subscribe to it at all, in the sense that once they put up the pay-wall, I tried so many avenues to subvert it, and I refuse to pay for the New York Times. It’s such a capitalist endeavor. They want to be the ultimate authority in terms of history; that is, writing the front page of history in the United States and throughout the world.

DS: As Seymour Krim once called the Times: the “commissar of the real.” The book is an attempt to show the undergirding, fictional framework of the commissariat.

RB: And yet the very fact that you have to pay for this type of information begs the question, Do you not want the public to have knowledge? The purposes of the Times have become indistinguishable from the purposes of the government.

DS: I think that is what is dangerous about the book, and why I’m proud of it. It does try to unravel this very complicated mixed message that the Times sends. The Times, I think, has a very confused and confusing role in our culture. On the one hand, it pretends to be a paragon of the Fourth Estate; people say all the time that it’s the best English-language newspaper in the world. The first draft of history. “The Paper of Record”. “All the News That’s Fit to Print.” Etc.

…that is, the Times, on the one hand, pretends to be covering war but is essentially promoting it.

On the other hand, it’s hugely obeisant to the United States government and is hugely intertwined with the US government’s imperialist ambitions. I’m interested in the ways in which those photographs are a switching station between that very mixing of messages; that is, the Times, on the one hand, pretends to be covering war but is essentially promoting it.

In the introduction, I explain that this has historical and cultural and familial roots in the Times, namely, that although the paper was founded by a German-Jewish family, the Times was notably silent on the extent of the Holocaust. They didn’t want to be perceived as either too German or too Jewish. The Times was criticized for not reporting the depth of atrocity of the concentration camps.

And ever since, I argue in the introduction, over the last seventy years, essentially, the Times has overcorrected in this rather grotesque way. It has been hugely supportive of every military adventure of the US government with very few minor exceptions (that prove the rule). The pictures, in my view, are the exact emblem of The Times’ profound hypocrisy.

RB: I’ve read sections from Other People (forthcoming next year from Knopf), in which you talk about your parents, your father and your mother, and their influence and their roles as activists and journalists in your art and life. And on the cover of War Is Beautiful is a quote from Phillip Lopate, who says, “This stunning rumination on beauty as a hazardous material, this buzzing conversation between word and image, power and global politics, is something that could have come only from the singular brain of David Shields. We’re ever grateful for the risks he takes and for his finely honed moral imagination.” I’m not sure if I would ever use the term “moral imagination” to describe your work. It seems to try to do the opposite. It destabilizes what is considered moral. It definitely plays with the imagination, but it almost breaks the illusion of imagination to get at something heartier and trickier and more uncomfortable. Both of those terms in your work are always questioned. And I want to know, since this is on the front cover of your book, do you agree with Philip Lopate?

DS: Well, it’s very generous praise from Philip Lopate, a writer whom I greatly admire and who has hugely influenced and inspired me. Your point is well taken — I’m attempting to be not pietistic but to explore epistemological and psychic complexities when it comes to moral questions — but, yes, I do agree with you that War Is Beautiful would not be the work that you might expect from me, based on my previous books, because it’s pretty overtly political. As I wrote to you once, in a sort of kidding way, “See, I am Chomsky.”

I think of my work as indeed profoundly moral, just not in the way that term is usually used (see above). I think of my work as imaginative, too, again, not in the standard imaginative way in the sense that I’m not creating a work in which I’m making up “imaginary beings,” but I’m trying to deeply imagine what it’s like to live in someone else’s skin.

As Jonathan Lethem says in another quote on the cover, this book casts light back on previous works of mine, Black Planet, Reality Hunger, I Think You’re Totally Wrong, or even That Thing You Do With Your Mouth. Those works are meant to seriously but implicitly and complicitly engage moral questions regarding race, sexuality, violence, celebrity, mortality, etc.

RB: There’s also this idea in the book that war is somehow a masculine desire, or that it’s somehow an inherently male preoccupation. The book argues that women can generate life, whereas the male body, in order to compensate for that, goes to war. So I wanted to ask you, If war is inherently a masculine desire, what is female desire?

DS: I’m not sure if the book specifically says that war is exclusively a male provenance, though, does it? One quotation goes to that idea.

RB: Well, I was looking at the photographs. And I think there are very few female soldiers. There’s one of an injured, female soldier playing basketball with a male soldier.

DS: I tried to find glamorizing, color, front-page photos of female soldiers, and there were few if any.

RB: I would say the gender dynamics of the book are left unquestioned. If we take out these rather traditional gender dynamics, who creates war? Is it men fighting to dominate and have authority over other men and other countries and other peoples in order to exploit them, to colonize them, to take advantage of them? Or if you remove the male figure, what would the female figure do? Would she do the opposite? A lot of people theorize rather rhapsodically that women are very community-oriented and that they would bring peace if they were the world leaders. But then you have rulers like Indira Gandhi, who was one of the most divisive prime ministers in India, and she caused a lot of bloodshed.

DS: Margaret Thatcher. Golda Meir.

RB: So women in power aren’t exactly the mother figure once they assume that role.

DS: Right.

RB: Get a bunch of women together — get twelve or fifteen together — and that is war. It’s absolute war.

DS: I guess I’d say masculine aggression often takes the form of violence, whereas female aggression is usually subtler, more psychological — something like that?

RB: In a weird way, the whole idea of the father in the book is very phallocentric. Such as in the Pietà section, where the fallen figure evoked is that of Jesus Christ and the figure who should be embracing him is that of Mary. But the mother figure in these images is always replaced by a man. It’s fascinating, because just a few images of women are featured. There are some images of women in hijabs. Overwhelmingly, though, the imagery is that of men embracing other men or men destroying other men. Only in the “Love” section do women finally come back.

DS: And in the Beauty section.

RB: Again, it’s the male gaze.

DS: I had a number of photo assistants who helped me pull the digital images. And many of them are women — undergraduates and graduate students. And some of them said, Can’t we bring in more pictures of women? And I said, “Find them.”

RB: Interesting.

DS: They’re not there.

RB: As you were looking at the front-page images of the New York Times, did you see images that were grotesque or repulsive or not beautiful? Is this something that you encountered as you reviewed all of these thousands of images?

DS: I was very open to being course-corrected, to my original impression (accumulated over many years) being proven wrong, but there were no, or nearly no, color images on page A1 that come close to conveying the horror of war.

Elizabeth Cooperman co-edited with me a book called Life Is Short — Art Is Shorter: In Praise of Brevity. She’s working on her own book about impasse, and I found myself texting her a note in which I said, “You have to be opportunistic. You’re not solving for X. Symptoms, not cures.”

…I’m not a political scientist. I’m trying to create provocative metaphors.

And I don’t know if you agree with that, but in a way it’s kind of an acknowledgement that finally I’m not a political scientist. I’m trying to create provocative metaphors. Okay, here are 64 images. Can one shoot possible holes in it? Go ahead and try. In a way it goes back to your question about moral imagination. I do think that if I have imagination, it lies in finding a metaphor that gathers and generates energy: the metaphors underlying Reality Hunger or Remote or Black Planet or War Is Beautiful.

RB: Well, I think that’s the intrigue of reportage: that we pretend to be objective. If you try to describe a phenomenon, maybe you are allowing it to have a chance to speak for itself, in the sense that it’s not totally overwhelmed by your persona or your ego or your desire to get a certain kind of reading or data out of it. How can you be fair and still be a challenger?

DS: “How can you be fair”? There’s no such thing as fairness. All is fair in love and war and art. The value of a work of art can be measured by the harm spoken of it, as Flaubert said. On some level, you’ve ultimately just got to go with your intuition. These images, I just know, are glamorizing war.