interviews

A New Kind of Apocalypse, a conversation with Theo Gangi, author of A New Day in America

If aliens were to use our fiction as an accurate representation of our real history, they’d think civilization fell apart in the early 21st century. Everywhere one looks there are apocalyptic signs in our literature: the cats of Robert Repino’s Mort(e), the Shakespeareans of Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven and of course, every single person you know in either a writing workshop or MFA program who has just written a story titled “They Might Be Giants, They Might Be Zombies,” or some similar kitschy-knowing fare.

Enter into this, an unlikely apocalyptic-writer; Theo Gangi. Theo is a Brooklyn-based-writer, but he doesn’t write the kind of stuff you’d normally associate with Brooklyn-based-writers. Starting his career primarily as a crime writer with the novel Bang Bang, Theo recently turned his talents to a unique and under-the-radar apocalyptic novel; A New Day in America, published by James Frey’s ebook company, Full Fathom Five. If Gangi is an uncommon phylum-less writer, then his new book is much the same; an apocalyptic novel with Victor LaValle’s wry grittiness combined with the rapid-fire writing style of a hard-boiled crime novelist.

I talked with Gangi about race issues at the end of the world, apocalyptic Brooklyn versus apocalyptic Manhattan, and where an iconoclast like him weighs in on the genre wars.

Britt: A New Day In America is not the average post-apocalyptic novel. Did you feel wary of the genre? Were you afraid of certain tropes?

Gangi: When I wrote the first draft, I deliberately avoided reading PA lit, so yeah, I was a bit wary of tropes. The problem with that approach is you might write smack into a trope on accident. I knew I did not want zombies. It’s like the first thing I tell people. I say ‘I wrote a post-apocalyptic book and there’s no zombies.’

Britt: Outside of your book, what makes a great apocalyptic story? Do you have any favorites?

Gangi: Books that illuminate the human values that will endure the devastation. People often confuse apocalyptic literature with nihilism. Nihilism to me is just laziness. A few years ago, Neal Stephenson called on sci-fi writers to stop being so damn pessimistic. One of my favorite PA books is Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle for Leibowitz, where a group of monks risks their lives to preserve literacy and knowledge after the fall of civilization. Also Philip K Dick’s Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? Deckard’s motive is to own a real sheep, and he is ashamed that all he can afford is an electric one. That was always very touching to me — that we would miss the dying natural world so dearly that we would take care of electrical animals and crave real ones.

A good PA novel challenges our notion of ourselves. We only know who we are by the context of our social and infrastructural reality. I think we collectively itch to know who we would be without the world we’ve shaped to. A novel is a good exercise in that hypothetical. We wonder what decisions might confront us. Will we, when the time comes, make the moral decision or the practical one? Which choice serves the most good, idealism or survival? Is survival akin to a moral imperative?

With the pillars of society stripped away, all that is left is the enduring human spirit. Sure, there will be the savagery and ignorance that’s a constant throughout history, but also the love, honor, sacrifice, the soul. As Faulkner said, ‘man will not merely endure; he will prevail.’

Britt: We’ve seen New York City destroyed in a number of ways throughout the years in novels, films and TV. But is it more fun to destroy Brooklyn?

Gangi: Super fun to destroy Williamsburg.

Britt: Could you have survived the things you describe Nos experiencing? Do you personally fear the end of days?

Gangi: I fear the end of my days. To paraphrase Woody Allen — I don’t want to achieve immortality through my work, I want to achieve immortality by not dying.

Britt: Can you tell me a little bit about what role race and ethnicity played in how you wrote this? We don’t see a lot of black protagonists of this kind of sci-fi survival story. Why is that?

Gangi: I suspect it’s for the same reason there aren’t a lot of black protagonists in most genres. People often think a black protagonist is a genre in itself. My first book was a crime novel called Bang Bang. At Borders bookstore (RIP), it was shelved in the African-American Lit section. For no other reason than that the protagonist was black. He was also half Jewish, but Bang Bang never made it on the Judaica shelves.

In terms of sci-fi/fantasy, I’m sure it’s in part because the readers are predominantly white, and publishers and studios want characters that their audience can relate to. But I think that’s incredibly shortsighted. Junot Diaz talks about how there’s a natural affinity between people of color and genre fanboys and fangirls. Anyone who feels marginalized by mainstream American culture. There are great sites like blackgirlnerds.com that show this audience exists and is really enthusiastic.

Even as a kid, I never understood why there weren’t more characters like Chris Claremont’s Storm from X-Men. She’s a black character, her blackness is inseparable from who she is, but it never defines who she is, any more than it defines the genre she appears in. I mean, she’s a freaking weather goddess. And she’s such a badass character that her best storyline is when she loses her powers and fights mutants bare-knuckle style in the sewers. Fox Studios needs to get it together and give Storm a proper vehicle. She has about as many lines as there are X-Men movies.

When writing Nostradamus Greene, I wanted a black American hero whose race is integral to who he is but does not define who he is. His decisions and actions define him: His commitment to push himself to near superhuman limits to keep his daughter alive. His ethnicity and history is a part of that. Nos was set aside by his father — a self-hating Dominican cop in Brooklyn who wanted more than anything to be an Irishman. So Nos’ devotion to his daughter Naomi is in part retaliation against how his father rejected him. Nos is flawed — prone to anger, violence, pity and despair, and in spite of that he finds a reason to live that is greater than himself. “Anyone with a ‘why’ to live can overcome any ‘how’.”

Britt: There’s a great joke in the beginning about Denzel Washington is Denzel Washington as Denzel Washington in Denzel is Pissed. Is there a stereotype about the “badass” black male? When does it work in fiction? Or, to put it another way, could we never “buy” Samuel L. Jackson as a Jedi Knight because of that “angry” stereotype?

Gangi: Starring Denzel Washington.

Great question. I think this one is less about the ABM (Angry Black Man) syndrome and more about our American confusion about ‘blackness’. When people say ‘he sounds black’ they are really referring to an American regional dialect, not race. In other words, if Sam Jackson grew up in Manchester, England, he wouldn’t sound like Sam Jackson, he’d sound like a Manc. The Pulp Fiction Samuel Jackson with the wallet that says ‘Bad Mutherfucker’ has that trademark attitude that doesn’t quite scream ‘Alderan’. I love Samuel Jackson but this role wasn’t in his wheelhouse. He’s clearly trying to tamp dawn his Sam Jackness in the films, and it hurts the performance. Heavy American regional accents often don’t work well in sci-fi/fantasy. You don’t want to hear a Detroit 8 Mile accent in Westeros or a southie accent in Mos Eisley. Kinda ruins the illusion. Everyone loves James Earl Jones as Darth Vader, and he doesn’t exactly have the pipes of a white man. And when he says ‘tear this ship apart until you find those plans,’ that is one angry black Jedi.

Britt: Your first novel was a crime novel — Bang Bang. Do you see this book as a departure?

Gangi: For sure. I got burned out on crime novels and became obsessed with books set in speculative ‘elsewheres’ — historical fiction, fantasy, sci-fi, etc. I had to try my hand at world building. I suspect I’ll return to crime one day. I have a high chance of recidivism.

Britt: So far in your career you’ve got a lot of labels: crime/mystery and now sci-fi/dystopia. How do you feel about genre labels? Love them? Hate them? Indifferent?

My biggest problem with genre labels is how insufficient they are. There’s so much more to a book than concept and setting.

Gangi: I think they’re a necessary evil. Genre labels are reductive, they box in readers, and that in turn boxes in writers. But the bottom line is this: You need to know what neighborhood you’re in. My biggest problem with genre labels is how insufficient they are. There’s so much more to a book than concept and setting. Writing style, dialogue, mood, pace, scope, character development — these are all crucial elements of books that current genre labels fail to address. This directly impacts the way books are written. If your approach to character is more like the repartee of an Elmore Leonard crime novel, but it’s set in a dystopian future, readers who like your style will never find your book. Just because you write dark fantasy doesn’t mean you’re interested in sinewy arms and heaving bosoms. But because our genre labels conflate style, character and concept, that incentivizes sameness.

I think a possible solution here might be an algorithmic one. According to an article in The Atlantic, Netflix has 76,897 unique ways to describe types of movies. It’s easy to make fun of the absurd specificity of ‘Visually Striking Latin American Comedies’ and ‘Evil Kid Horror Movies’, but there’s a seed of innovation here. The challenge is for the intangibles of content to be represented by their labels. So someone who likes gritty, suspenseful stories will find a ‘Gritty Suspenseful Revenge’ category, a ‘Dark Suspenseful Gangster’ category, and a ‘Dark Suspenseful Sci-fi’ category. Whereas the literary genre equivalents would be ‘Thriller’, ‘Crime’, and ‘Sci-fi’. A devoted crime fiction reader would never find sci-fi book, even though that might be right up their alley. Jim Butcher fans might really like a moody mystery novel like CB McKenzie’s Bad Country. If they were in a bookstore, it would by almost physically impossible to find a title outside their genre. The Internet is capable of this sort of aggregation. I’m optimistic.

I have a great admiration for the loyalty of genre readers and writers. There are really solid communities of sci-fi/fantasy writers and crime/mystery writers. They read each other, support each other, and share a cannon of great works, and have a lineage of important writers creating in conversation with one another. I do find (with notable exceptions) that they often aren’t aware of one another. There were two books that came out in 2007 called The Blade Itself. One by the crime writer Marcus Sakey, and the other by the fantasy writer Joe Abercrombie. Both books are absolutely terrific. Both writers were a big hit with their respective fan bases. And there was zero overlap. If you ask a fantasy fan ‘did you read The Bade Itself?’ They won’t ask, ‘which one?’ They only know the one. Same with crime readers. I still haven’t spoken to anyone that read both books.

Britt: In what ways does your writing style mash-up genres?

Gangi: I’m a sucker for a showdown. Verbal sparring between the hero and the villain, or the hero and the love interest. That kind of slick talk that flirts with the edge of danger but never quite crosses the line, until it does. Elmore Leonard was the master of this. He started his career writing westerns. He took that high noon style and put it in contemporary crime novels and it worked. George RR Martin masterfully works showdown dialogue into Game of Thrones. I think it’s the Bayonne, Jersey disguised as medieval English. The scene when Theon Greyjoy first meets Asha Greyjoy is right out of an Elmore Leonard novel, when the hero meets and flirts with the prospective love interest. Of course, in Martin’s world, the love interest turns out to be his sister.

It’s a quality I associate as classic Americana. That style of verbal measuring and greasy talk is a big part of Bang Bang and a big part of A New Day in America. If it works in crime novels, it works in westerns, and it works in Westeros, it will work in the apocalypse.

Britt: What are influences on your work that some might find “unlikely.” For example: are you writing while listening to the Muppets soundtrack or something?

Gangi: Ha! I went back to my formative years and read the Japanese magna The Lone Wolf and Cub. Not sure if that’s ‘unlikely’ as that story cornered the killer-father-with-child concept. The landscape of feudal Japan felt right for the apocalypse. Samurai assassin Itto Ogami and his son Daigoro serve as a great model for Nostradamus Greene and Naomi. Apocalypse stories, while set in the future, are actually a return to the past. The time after modern civilization would resemble the time before it. The paradox of the killer-father character has a brutal simplicity. A man with a gun is a killer. A man with a gun and a child at his back is a hero.

Britt: This is becoming a question I ask of so many writers now: Imagine it’s 100 years from now and your books are being taught in school. What is some stuff people might misinterpret about your books?

Gangi: Tough question. It depends on what genre of 100 years from now we’re talking about. Is this an advanced society where terabytes of old novels are being aggregated by synthetic intelligence so computers can learn how to ‘love’? Is this future a wasteland where literacy is endangered and scraps of pages are being smuggled by book runners to save the written word from extinction? Or is this a future where students can travel 100 years back in time and ask me a series of questions? What I’m really asking is, are you from the future?

Britt: Sci-fi and adventure stories often don’t feel like they are autobiographical. But, how much of this was drawn from your own experiences? If not in the logistics, then in the emotional reality of the book?

Gangi: It’s the thought of protecting your family that really centers the book. Nos Greene kills a lot of people, which isn’t really something I can personally relate to. Then you imagine your child’s survival depends on you killing all those people. Then it’s like, ok sure, if it would save my daughter’s life, I’d kill everyone. I don’t even have children — just a wife and a dog. I’d still kill everyone.

Britt: What’s a book everyone loves that you don’t love?

Gangi: I’m a bad person to answer this question, as I’m a firm believer in not reading books I don’t like. There’s just too many good books and too little time. I think reading a book you’re not into is like being in a bad relationship. You’re dating someone you know you don’t like and you know it’s not going anywhere, but you keep calling them anyway.

That said, to answer the question, any book by Paul Auster. Bad fit, I guess.

Britt: What’s next?

Gangi: Sequel! Tentatively titled Another Day in America. The second in a trilogy about the quest for the cure amid America at war. I have a crypto-thriller called DARKER in the works, about an obsessive, voyeuristic society and a live-feed murder lottery network called Crap Shot, where gamblers place bets on killings. I also have a middle-grade children’s fantasy series tentatively called Elseweyr I’m working on, about a little girl named Else who can turn into an eagle. I know that sounds like an improbable genre jump, but after writing about gangsters, homicides, the apocalypse and live feed murder for 10 years, it’s nice to lighten up and turn into an eagle.

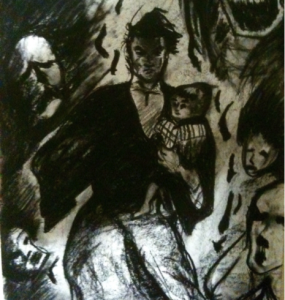

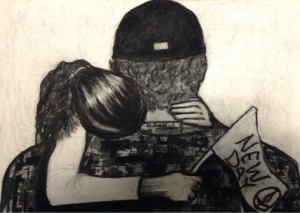

Original artwork by Theo Gangi