Books & Culture

Anatomy of a Commission: On Publishing Lydia Davis

by John Freeman

So many writers I admire came into my life when I was looking desperately for a way to live. Lydia Davis is one of them. I find it hard to pry my feelings about her work from the period when I first began to read her, thanks to a friend in publishing, who I realize now — twenty years later — was giving me books the way a junky pharmacist indulges a long-time customer’s habit.

I was living in those days on the Lower East Side in an apartment vacated by three goth musicians. They had painted the walls blue, the ceiling silver, and left behind a doorframe-mounted black light, which in parties lent your teeth a ghoulish glow. This was 1997, the beginning of the run-up to the first dot com boom, and if you were of my generation, people came to parties with glow sticks in their cargo pockets.

Anyone who was literary seemed to be reading Rick Moody stories, or Kathy Acker if they were more adventurous, books that scratched at or peacocked their punk edge. I was an editorial assistant at a large house in Midtown, and had just graduated from college, so I was reading anything that anyone said was good. So many firsts that year: Catch-22, by Joseph Heller, Night, by Elie Wiesel, White Noise, by Don DeLillo, Song of Solomon, by Toni Morrison, The Giant’s House, by Elizabeth McCracken, a book so good I walked to work with it six inches in front of my face, the way people now navigate with their phones.

Early that year, I quit my job at the Midtown house to go work at Farrar, Straus & Giroux in their sub rights department. It was one of the best jobs I ever had — they looked at you funny if you arrived before 9:30 or stayed much later than 5, and encouraged you to read what was on the shelves, which was everything from Sontag to Brodsky and O’Connor, Kerouac and Paley. I basically had a series of administrative duties and one perk task — to write a letter a month to a book club pitching them a book everyone knew they’d never take. The Lives of Insects by Viktor Pelevin, say.

I had trouble doing this much. My roommates then were two friends from college. We all had girlfriends, and all of them — in that year — dumped us, so we went from being studious, letter-writing sorts, to frequent patrons of a downtown dance club called Robots, a techno dance bar that stayed open until it was light. It was a rare week that we didn’t stumble out at least twice at six or seven, eat breakfast, shower, and take cabs to our various places of work. I once ran into a friend from the Midtown house as I stumbled out of my cab, and she laughed at the supposed extravagance: on some days, it was the only time I’d slept, on the 20 block ride to Union Square.

If you want to know what it was like to work at FSG in these times, Boris Kachka’s cultural history is a great place to start. Robert Giroux, who had nurtured and published everyone from Kerouac to O’Connor, came in a few days a week. So did Arthur Wang, who had published Night some forty years before with a $500 advance, something I knew because the sub rights department had just relicensed it for seven figures to a paperback publisher and I’d had to pull the original contract. Such a powerful lesson in knowing that what becomes central to culture often comes from its margins.

The writers, too, would stop in, more like the place was a writer’s colony than a publishing house. I’d pass Jonathan Galassi’s office and there would be Jamaica Kincaid or Charles Wright or Grace Paley bent over their manuscripts like monks at an abacus, while Galassi typed away at his desk. The house then had an odd policy which is perhaps ingenious in that it circulated everyone’s correspondence to everyone in the company. Once a month a huge binder would land on your desk, full of editorial letters, quippy, manual-typed notes from Jeff Seroy, fire-breathing contract dispute harangues from Roger Straus himself, who would tour the office in the morning dispensing good news, hands on his waist coat like a baron on his estate talking to the farmers about crop yields.

**

For A 22-year-old, it was at once a great education in the way publishing is built on relationships, but a little like visiting Mount Rushmore to discover that the people on the mountain face were still very much alive and needed a drink. Happily, these legendary figures didn’t create a climate of masculine chest thumping — one of the biggest figures after all was Elisabeth Sifton, who had brought John Ashbery back to FSG — but rather of mentorship. Two of the younger editors, Ethan Nosowsky and Paul Elie, had a knack for taking young assistants aside and pressing books on us. At least I assume they did this for other people. Ethan gave me Geoff Dyer’s But Beautiful, which had just been published in England, and Anne Carson, who he wasn’t even publishing. These are strange books, I don’t know how he knew tales of failure and Grecian love would appeal to an ex-high school athlete from Sacramento, but there it was.

Paul, meanwhile, was the sort of reader who didn’t present you with books but implored through the centripetal force of his own passion. He caught me one day skulking along the shelves and told me he used to do the same thing, then broke out into a reverie about Lawrence Joseph, the poet and lawyer whose strange, Stein-like prose work — Lawyerland — FSG had just published, and from there into the weekend he spent reading Jonathan Franzen’s first (and only then) two novels, Twenty-seventh City and Strong Motion. 1000 pages in a weekend in one long gulp, he said, or something like that, and having spent a lot of my weekends in similar vortexes, I pulled the books from the shelf and went to do the same. Franzen, after all, had been a student at Swarthmore, the school I’d just graduated from, and which produced so few writers he was a kind of talisman those of us who wrote waved at the possibilities of our own failures.

It took me more than a weekend to read the Franzen, largely because around this time my girlfriend began to ghost me, and I responded to this in the worst possible way, which was to make unannounced sudden trips back to Swarthmore, where she was still studying, a year behind us. This never went well. On one visit, which coincided with a genderfuck dance — where everyone cross-dresses — my friends and I got stoned, put on skirts, tank tops and heels, and tottered up the hill to the social hall only to discover my girlfriend on the dance floor kissing another guy. A month later, one of my friends drove down with me and my girlfriend wouldn’t let me into her room, and I spent half a night speaking to her through a door — I wasn’t the brightest bulb, but even then I knew it was quite likely she wasn’t alone.

I was learning then a new language of intimacy. That to say “I love you” was in no ways protection from the harm someone you love — and who loves you — can still do to you. That there are some forms of love that are like insanity, and the only cure to it is are greater types of lunacy. And in the middle of all this: that love was not a side-show to living, an also or a perhaps, it was the only thing. As in to live without love, however much it damaged or made me bleed, would be as impossible as to stop breathing or reading. It would mean a suspension of why I felt living was worth it.

It was the best time in the world to start reading Lydia Davis. Franzen, in his own way, had been a help because Twenty-Seventh City and Strong Motion were books about love disguised as books about societal structures. They were novels trying to bootstrap from DeLillo toward a greater emotional intimacy. Davis, though, was down in the trenches. “I get home from work and there is a message from him: that he is not coming,” begins “Story,” the first piece in Break it Down, then the most recent book of hers when I worked at FSG. I’d pulled it off the shelf when I’d come back into the office after my seventh smoke break before noon one day at the recommendation of a friend, who probably saw the shit-show that was my life.

Back and forth I went to Swarthmore, to worse and worse news, reading and rereading those early stories. I say early, but Break it Down was published in 1986, when Davis was 39 and had already translated some twenty books, and had two small press collections out. By the time I was reading it, she’d published a novel and had another one about to come out. She was hardly new at the game, and some of her stories were by then twenty years old, but they felt like poisoned darts that had just been made.

The writer, I learned in reading these stories, was a kind of fletcher. That even if the topic was love, especially, perhaps, if it was love, that her language had to be precise, exact, and unsentimental, if a story was going to hit its mark. That only concision could tell you what love felt like, how it moved and behaved in the air, and only a ferocious attention to language could find the stress points where it failed. For Davis, these aberrations that drew her arrow off target, were both the place narrative broke down and story began.

**

Back at FSG, Davis was then almost ten years off from getting her National Book Award nomination, fifteen years away from her International Man Booker. Ten years, you type it and it feels like nothing, but to live and work for ten years hand to mouth, or with small but loyal readership, is a thing I think a writer never forgets, never grows out of. Anyway, I was properly then and since have been obsessed. The publicist working on her upcoming book at the time was the sort of guy open to ideas, so I suggested he set up Davis and Franzen to read at Barnes & Noble since they seemed to be on the same wavelength of sorts, and, well, why not?

I think about eighteen people came. But they were an engaged eighteen. Davis wore a scarf and had the steely briskness of a woman used to reading serious work to small crowds, and Franzen was carrying the invisible weight of the unfinished Corrections on his shoulders. He was not followed into the store by fans wanting to steal his glasses. Standing next to Lydia Davis put his tongue in traction. He read what had appeared in Granta or another magazine, the opening section of what went on to become The Corrections, which was funny, much funnier than anything he’d written to date, and I don’t remember what Davis read, except that it whistled through the air perfectly. Working on this reading was one of the last things I did at FSG before my boss and I agreed it was probably time I start looking for a new job.

Around this time, my girlfriend — who was then my ex-girlfriend — moved to New York, took a job I’d arranged for her in my ex-Midtown-publishing-employer, and was living somewhere in the city, an invisibly occupying force. This was before cell phones and email, but also all of social media. You couldn’t stalk someone online if you wanted to, so when they were gone they were truly ghostly. She wouldn’t tell me where she was living, but I knew where she worked. I’d learned the hard way the drop-by went very badly, so I did the next best thing — or what felt like it — at the time. I’d bought a copy of Break it Down, had Davis sign it, and sent it to my ex at work by messenger. The title story, if you haven’t read it, is one of the world’s best break-up stories ever written. It’s about a man looking back on a weekend spent with a lover, trying to amortize the pleasure and pain against his expenses.

“You’re with each other all day long and it adds up, it builds up, and you know where you’ll be that night, you’re talking and every now and then you think about it, no, you don’t think, you just feel it as a kind of destination, what’s coming up after you leave wherever you are all evening, and you’re happy about it and you’re planning it all, not in your head really, somewhere inside your body, or all through your body…”

The story is a clinic in a voice and the crazy relentless non-reasoning of love. Being on the downslope of this arc, when love appears to have cost you about 2.50 an hour, I sent the book and waited. Waited for a teary call full of pleas of forgiveness and absolution. I waited and I kept waiting. And when days turned to a week, I finally decided I couldn’t wait any longer I called. The book? What book? The book, she said, had never arrived. The book that had told me everything, and had been my solace, had simply vanished. It was as if I never sent it. It occurred to me not long ago, that of course the book had arrived. It was the end, though, and what better way to formalize that then to simply stop hearing what I was saying?

**

I have worked with Davis three times as an editor now, not a lot, but enough to discover — alongside two decades of reading — that what made her such a tremendous writer on love, makes her capable of writing on just about anything. The way her stories tighten and tighten around the narrator’s assumptions and build a kind of pressure is an effect that illuminates many altered states. Moreover, what Davis was good at wasn’t just laying bare the bad bargains of the heart, but the way the mind was often its chief arbiter, its coconspirator, the mortgage agent working the numbers, making the purchase possible especially when it was ill-advised. What she was wasn’t a love junkie, but one of the greatest descriptive writers of consciousness in the last few decades.

When I edited Granta, I asked her for a story for an issue on women and power and she handed over a fantastic, satirical riff on a woman adding up the infractions of her domestic help, “The Dreadful Mucamas,” featuring two women from Bolivia who do not make the toast right and gradually begin to thwart the narrator’s growing desire for control. A few years later, I was putting together an anthology about New York and its radical income inequality, and Davis sent in a new story, about a woman on a subway which is stopped mid-tunnel, between Brooklyn and Manhattan, and the rising fear she feels as loud young men walk through the cars with impunity. Very little I have read set in New York describe the ways in which all of us develop antennae for danger, and how much these tuning devices say about us and where we fall on class structures.

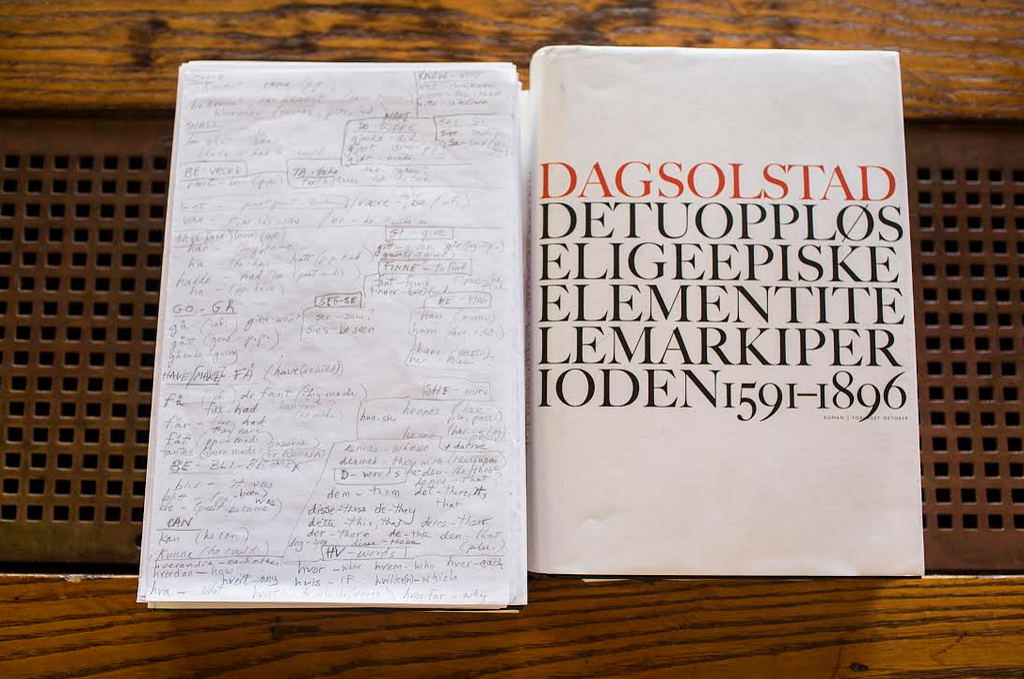

I had wanted to ask Davis to write something for the first issue of Freeman’s when I began to put it together, but I didn’t think it was likely because I had just finished working on and publishing her story in “Tales of Two Cities.” Some writers always have something new — but Davis struck me as a kind of comet that came every three years. Then I heard a story last summer in Norway. I had traveled there to interview Tranströmer for a Norwegian newspaper, Morgenbladet, whose literary section is edited by one of the better book minds I’ve ever come across — Ane Farsethas, a sort of literary detective and semiotician and den mother rolled into one. We got to talking about the upcoming Nobel, and I asked whether Dag Solstad, who read the weekend I first met Ane, would ever win. She wasn’t sure, but she did know that Lydia Davis was attempting to learn to read Solstad, and that Davis — for whatever reason — would always translate something back into English whenever her books were translated. The image that stuck with me was that Davis was learning a language by reading one of its most difficult novels.

It’s worth a tiny parenthetical here to describe what Dag Solstad is to Norwegians. Imagine if Philip Roth was a committed postmodernist — and much more political — and you get a sense as to what Solstad is to his nation. He has won the Norwegian critics prize three times, and yet he is an outsider. His range is broad and deep, but his books never stray far from the essential questions of what role an individual plays in a larger society, how he or she exercises their moral agency. He has written novels on Norway’s involvement in the recent Afghanistan war, five books on the world cup, existentialist leftist novels (earlier in his career), and several books in which a character runs fast into one of the ideas he has held dear in full fledged form. Attempts to Describe the Impenetrable revolves around an architect’s retreat into the suburbs (of the European sort — which are basically planned public housing) and what he finds his ideas have wrought.

It took some time for the first issue of Freeman’s to coalesce around the theme of arrival. At first I’d considered food — and then another magazine editor gleefully took that theme right out of my hands. Finally, after stories from Haruki Murakami and Aleksandar Hemon and Tahmima Anam all gathered around the notion of arrivals — how we go from one place or state to another — it occurred to me that language was in its way, especially a language foreign to us, a kind of landscape. Something that seemed majestic at a distance but strange and other and quite rocky sometimes when you were trying to move over it at close range. Given that Norway had raised some of the worlds greatest explorers, how great if someone of Davis’ caliber could do it the credit of showing what it was like to walk across its linguistic tundra in return. “I wonder if you’ve ever written about learning a new language” I wrote to Davis, “treating it as a new landscape or terrain you’re moving across. I gather from friends in Norway you’re deep in Dag Solstad and learning Norwegian along the way.”

The idea — of getting Davis to write about translation — was so obvious I figured there was a good chance someone else had gotten there first, an editor’s constant fear, but it turned out it was not another editor but Davis herself, who’d proposed to another paper to write a short piece on the impulse to translate and get outside one’s language, where it came from and why. Perhaps I could simply run an expanded version she wrote back? I was very tempted, but I worried if the first issue of Freeman’s contained even very partial reprints it’d slip into the blurry territory of an anthology of recent writing rather than a journal of sorts of new writing. I skulked off, prepared to try to not to see the hole of that imagined piece in the finished issue, only Davis returned, and was determined to write a bigger piece, something around 3,000 words, which for her would have been one of the longer essays she’d written to date. It was mid November by then, and so the deadline would be somewhere in the early new year. I said yes, let’s do it.

Early this year she began to write wondering if there was any upper limit on the word count. I have always felt as an editor a piece should be as long as it needs to be, not as long as the space allows, which is why I think I’ll probably end up staying in literary journals, where space constraints are purely theoretical. Granta, before I got there, once ran a piece that ran to over 100 pages of an issue. Ian Jack writing on a murder in Gibraltor. It was a marvel of reporting. I started Freeman’s in hopes that one day I’d find a piece like that, something that didn’t demand space but required it. Davis’ essay turned out to be that piece. A week later she wrote again, asking around the idea of space. And then a week before she turned in she warned me, it’d be long. On the day she delivered the piece we’d both thought would be a 3,000 word essay it was coming in at 21,000 words. In other words, it was 2/3 of a small book.

I have never read anything like this essay. So often, the mind at work is dramatized through narrativized consciousness, and all the tools of storytelling — compression, elision. You don’t get thought, but the story of thought. Davis had managed, without being remotely tedious, to show the way thought moved in almost real time, solving problems, wiggling around obstacles, lifting moveable ones, and running into dead ends. It wasn’t that language was the landscape — as I had imagined, the landscape was thought itself, and language was not like nature, out there, other, but part of that terrain’s continuation. To work with language, Davis’ essay showed, was to work against alien and yet oddly familiar extensions of one’s own basic building blocks of thought — like an amnesiac detective retracing her steps. Her method felt like the way someone would orient around certain blind spots:

my method of figuring out the words: cognates

After separating a word into its parts, if it’s a long one, I can usually figure out the prefixes and suffixes easily enough: un-, or up, or out, or to; -ly, or -able, or -ness, etc. I search my mind for what may be the possible cognates of its root — the essential, core part of the word: e.g. “pend” in “independence”. A cognate may give me the answer to what the word means, or at least a hint.

Here is an example of a short word and its cognate: if a bekk runs through a farm, a handy source of water, and if one remembers the Northern English word beck, then one can assume this is a little stream.

Here is an example of a large sentence fragment that can be understood entirely via cognates: One of Solstad’s regular “connecting” statements, in his narrative, is: “Vi skal komme tilbakke til…” = “we shall come to-back to…” (All English cognates.)

Sometimes I was able to find the cognate by removing that strange (to me) j that seemed to creep into certain words: remove the j from kjop and I would nearly have the Dutch koop, meaning “buy.” Remove the j from gjerne and I would be closer to the German gern, “gladly.”

The essay continues at this intensity for another 20,000 words, blending the story of Davis’ expedition with the tale of the Solstad’s book and a larger arc that has to do with how possessions come and leave us, a familiar Davis topic. It’s breathtaking and cut with a precision that calls to mind the laser tools of jewelers, a type of word-nerd ice-sculpture. Upon reading it, I felt, here is a book, not just an essay, and almost right after that, I need some help. I could edit as a reader — identifying repetitions and places where the narrative snagged on too much information. The truth was, there was not much of that at all. It was an astonishing piece because it showed that thought was its own form of narrative. But I couldn’t help with the Norwegian. I had no idea if Davis was right or wrong in her use of the language — I suspected she was right most of the time — so Ane and I combined forces, to co-edit a piece, with the idea that she would publish some of this in Norwegian and me the whole thing in English.

We worked on the piece steadily for about two months after it came in, and with further periods of intensity around galleys and an unfortunate bit of aggressive copyediting. To commission a writer of this caliber is to enter into a magical space. When a piece is this good, it feels not unlike being present at the creation of a new wrinkle in reality. As an editor, you are out in front of that new Doppler wave, not behind it, and so all the things you typically carry — your self, your reference points — fall away, and the only thing to focus on becomes that piece, its shape, its contours, its need to come into being. It is the world.

At some point, though, toward the end of working on Davis’ essay, the world began to come back to me. I realized how long ago it was that I’d been a wounded 22-year-old on a train traveling to a crumbling relationship with nothing but a book of short stories to tell me what to do. Perhaps it really was chance that I was sitting in the seat I was now, catching for Davis’ fastball. But if it wasn’t, I’d spent almost 20 years getting ready with my mitt. In some ways, Davis’ example back then, as it was now, pointed toward the same instincts and behavior. Ones that are well-suited to any walk of life, but especially editors and writers. That to pay attention is key, and to never take the mind out of the equation, since without the mind — in matters of the heart, or the word, or, in the best of cases, both — we’re lost.

John Freeman is the editor of Freeman’s, the first issue of which features “On Learning Norwegian,” by Lydia Davis. He will appear at Tronsmo Bokhandel in Oslo Tuesday at 5PM with Ane Faresthas and Dag Solstad for a Freeman’s launch event.