Books & Culture

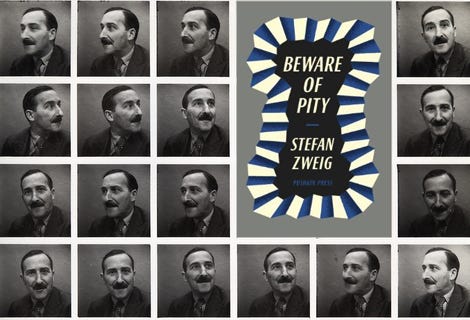

Beware of Memory: On Reading Stefan Zweig’s “Beware of Pity”

by Tara Isabella Burton

For years, Beware of Pity was the most important book I’d never read. I’d read other books by its author, Stefan Zweig: a melancholic Austrian Jew whose chronicles of pre-war Vienna filled me with an aimless nostalgia for Habsburgs I had never known. I’d loved them all.

But Beware of Pity–Zweig’s only novel–was the only one I was afraid to read.

I never admitted this to myself. I came up with excuses: I was too busy; I’d read enough about Vienna that month; the copy on the bookstore shelf was too expensive; all of these were lies. I was afraid to read Beware of Pity because the first man I’d ever loved had called it his favorite book, when I was 17 and an idiot, and he 18 and weighed down by his worldliness.

He’d told me about the book over one of our more awkward coffees, in that interstitial period between togetherness and estrangement engendered by our long-distance romance.

He summarized the plot for me. It was the story of a young Austrian officer at a dinner party who asks his host’s daughter to dance, only to discover that she is lame, and that his request has humiliated her. In a desperate effort to make amends, the officer begins to call on the girl more regularly, only to be drawn into a sickening cycle of codependence and guilt. In my lover’s description, the girl was an appalling predator, using her sickness as a net to lure in an unsuspecting and upright officer, hell-bent upon receiving romantic satisfaction at the price of his sanity.

We broke up not long after, and in the completeness of our separation I had nothing left of him.

It was only natural that I’d come across Zweig on my own. It was our shared love of the melancholy, of the nostalgic, of Sehnsucht for a world we’d never known or could know–Zweig’s stock-in-trade–that had first brought the two of us together. We loved so many of the same things. I loved, in my turn, The Royal Game, The Post-Office Girl, Letter from an Unknown Woman.

But Beware of Pity I could not face. To do so, I felt, would be too dangerous–like rifling through someone’s letters after a death. I would discover things about him, about myself, about us, that I would not be able to withstand. I would have no way of asking him what he meant, by responding as strongly as he had to the young officer Hofmiller, whether he saw me in the pale and crippled Edith, whether he loved the book because he believed, deep down, that the women who loved him were predators, and that he was bound to them by the hopelessness of guilt. I would be left alone with my own reading, my own questions: with the mirage of us suffusing every scene.

The choice to avoid the book became less and less conscious as the years went on. I idly downloaded a copy onto my Kindle, telling myself that I’d read it later. I moved on in other ways: I fell in love with other men, found a partner, learned about his own loves and fears through the books that he loved, that he lent me, that now line our shared shelves. I read the best and the worst of us in the stories we both knew.

Almost six years after my ex told me that he’d just finished reading Beware of Pity, it dawned on me that I was ready to read it myself. I steeled myself for the discoveries I would make, for the weaknesses–in myself and in him–I would uncover. I steeled myself for the story of a pathetic and manipulative woman who forced a hapless man to stay with her, despite having never loved her, and told myself I was past caring about that now.

But Zweig is a better writer than that.

The novel opens in 1938 with an older Hofmiller looking back upon his life. He is a decorated veteran, celebrated for his courage in the first World War. But he is also, as he tells the nameless writer that encounters him in a Viennese cafe, a fraud. He is, he tells his companion, one of those “deserters from their own responsibilities”–he bolted into war to avoid a greater burden of guilt.

Hofmiller is a coward, he tells us; he is a fool. He bumbles into his embarrassing incident with Edith as a result of his own ineptitude. He had arrived late, after all, and had not seen his hosts sit down to dinner, had not witnessed Edith on her crutches. He accidentally gives Edith false hope about the likelihood of a cure that will make her walk again. He leads her on romantically, unable to contend with the possibility that a lame girl might experience capacious sexual desire. He is well-meaning to the point of buffoonery, but his good intentions lead Edith into her own psychic hell.

At times, it’s true, I found myself disturbed at Hofmiller’s horror at Edith’s love for him, found myself achingly conscious of what it means to be a woman who once loved a man more than he loves her:

“She wants, she demands, she desires you with every fibre of her being, with her body, with her blood. She wants your hands, your hair, your lips, your manhood, your night and your day, your emotions, your senses, and all your thought and dreams… I now know that it is the most senseless, the most inescapable, affliction that can befall a man to be loved against his will.”

But where Zweig excels is not in his depiction of a proto-Lawrentian terror of the rapacious harpy, but rather in the complexity of what love–requited or not–might be. Hofmiller is repelled by Edith, but by the time he guiltily agrees to marry her, late in the novel, he finds–intoxicated by his power–that he is able to love the woman he has made happy, in spite of its genesis.

“Like a true lover, I postponed the moment of leaving the girl who loved me. How pleasant it would be, I thought, to sit beside her bed, stroking the delicate, tender hand in mine again and again, seeing the rosy smile of happiness light up her face.”

When Hofmiller at last, fatally, repudiates his love for Edith, it is due not to his lack of feeling for her but rather to his embarrassment at being connected to a woman seen by the town as ugly and undesirable. He denies his engagement to a group of fellow officers, though he instantly regrets it, and in so doing precipitates Edith’s suicide. His frantic attempts to reach Edith to explain are delayed, with catastrophic consequences, by the news of the assassination of the Archduke Franz Ferdinand. A new world order marks the young Hofmiller’s launch into adulthood: his crimes of the heart are mirrored, on a grander scale, by the global crimes to come.

I had expected a novel about unrequited love, and, to some extent, Beware of Pity is precisely that. But, far more important, Beware is a novel about the complexity of human emotions: about how people hurt one another without meaning to, about how love is as much borne of the happiness one can give as the happiness one can get, and how its absence is inextricably tied up with embarrassment, with shame, with the fear of proclaiming one’s love before one’s fellow soldiers, fellow men. It is about how Hofmiller grows up, with brutal abruptness, and realizes that he lives in a world far more complex, with boundaries between emotions far more easily blurred, than he expected.

The famous nostalgia that suffuses Beware of Pity is only illusory. Zweig’s heady and atmospheric prose comes close to convincing us that the world before 1914 was an easier, a simpler, a more beautiful place. But what we really mourn is not Austria’s innocence, but Hofmiller’s. By the time war dawns, at the book’s close, we know that it is not only the world that has changed, but Hofmiller’s perception of his place in it.

When I finished Beware of Pity, I did mourn: softly, in my own way. Not for the boy I had loved, nor for the man he has doubtless now become, but for our twinned innocence: for how unaware we both were, of how complicated the relationship between two people can be, how no easy narrative defines the way we love and lose.

I do not know if my Beware of Pity, read so many years later, is the same Beware of Pity my ex read, once upon a time. Perhaps he read it, after all, as a straightforward case of a man trapped into commitment against his will. Perhaps he read it because it was the sort of book a well-read teenager wanted to boast about having on his shelf. Perhaps he rereads it, now, and wonders, as I do, at the impossibility of easy answers, when it comes to two people in love.

If I had read Beware of Pity five years ago, it might have hurt me as I had feared it would. I might have read it as my own story: hated Hofmiller, hated myself in Edith. But reading it now, over hot tea in the midst of a polar vortex, I found myself hating neither of them, understanding them both. Feeling something like compassion, maybe pity. Maybe even love.