Interviews

Brad Gooch, Author of Smash Cut, Remembers Howard Brookner and Gay Culture in ’70s & ’80s NYC

by Stuart Waterman

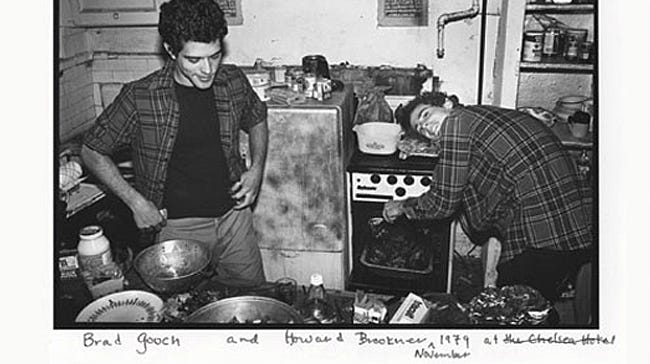

Smash Cut: A Memoir of Howard & Art & the ’70s & the ’80s by Brad Gooch was released in paperback in spring 2016, and is nominated in the category of Gay Memoir/Biography in the Lambda Literary Awards, which will take place during LGBT Pride Month this June. Smash Cut tells the story of Gooch’s relationship with Howard Brookner, the film director who was best known for Burroughs: The Movie about William S. Burroughs and who died of AIDS in 1989. More than that, Smash Cut is a remembrance of a particular time and place — the seventies and eighties in New York City. Gooch recalls 1970s New York with all its grit and danger but also its unprecedented sexual freedom and flourishing arts scene. From there, he takes us to the 1980s, when a modern plague struck some of society’s most vulnerable members and met with official inaction.

Gooch is the author of eleven books, ranging from novels and poetry, to self-help and literary biography. Flannery: A Life of Flannery O’Connor was a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist and a New York Times best seller. A professor of English at William Paterson University, he earned his PhD at Columbia University. Gooch lives in New York City, and is currently at work on a biography of the thirteenth-century Persian poet Rumi.

We met at his office in Chelsea, Manhattan, to talk about Smash Cut, Howard, seventies and eighties New York, and books and writing.

SW: What prompted you to write this book now? It’s obviously set in the seventies, and you’ve been living with these memories for a while, so I was wondering what compelled you to finally put them down.

BG: I think it was moving back to the Chelsea neighborhood, with my partner Paul, and actually not, when we got this apartment, really registering that across the street was the Chelsea Hotel where I lived with Howard for three years. And down the street was the London Terrace where he died, and up a couple blocks was this apartment I lived in during the eighties. Somehow, gradually, especially walking every morning to go to the gym and looking up at the Chelsea Hotel and seeing the windows of our first apartment there, it started triggering these memories.

SW: I’m wondering, on a practical level, how you write about a time that’s a couple decades in the past. I know I’m reluctant even to write about my childhood, because I find myself having to guess so many details and conversations and things that are just lost to me now. I’m wondering how you navigate that.

BG: There were a couple things. One is that, unlike childhood, I lived through it at an age when I was a writer and writing stories and sometimes writing journals and writing letters and things like that, so the camera in my head was already clicked on. The other is that it was this very vivid period. People were kind of aware of it as it was happening. People would talk about it at the time, how great, how much fun this is. There was a real sense that something was happening that was new and exciting. That helped. And then the other is the practicality of having some photographs, having Howard’s papers, having my papers, and even though I never really organized anything in the archival way, things did start popping up as I was writing. All that went together.

SW: I was very impressed that you held onto the piece of paper where he wrote his number.

BG: Amazing, right? And even that wasn’t, like, in a Howard Brookner file. We didn’t have cell phones and things. You would give people your number, and then you would have a folder with all these numbers in it — Jack and Fred, and eventually you’d have to clean it out, because there were so many and some people would stay and some people would go. And Howard — that sort of stayed. And it somehow made it to here.

SW: One of the audiences you mentioned having in mind was younger gay men, and I know a lot of gay men around my age, in their twenties and thirties, are very curious about the seventies as an era. What do you think the source of that curiosity is?

Everyone was making it up as they went along, and making up gay identity, which was pretty open, up for grabs.

BG: Part of it is that — well, I talked about it being a romantic time. And part of it was sexuality. There was no AIDS. We were coming out of a period of sexual liberation, not just for gay men, but for everyone, because of the pill. Sexuality for gay men at that point, it was open and liberating and it also was political, so it had some kind of meaning to it. All that was fun and exciting. It also made for a very democratic kind of experience. The social life of gay men, certainly at that time, cut across generations and cut across economic strata — for different reasons, partly because it was a small group, so you were excited to meet other gay people and you learned about gay history and who was really gay and what was going on, only by hearing about it from older guys who’d been around, since most of this wasn’t written down. Sexually, in these bars and clubs and things, it didn’t matter and you didn’t know what economic class someone was in or what their job was. There was this attraction that mixed everything up. Now we have these — I mean, I’m married, we have a baby, we have a whole different kind of life — some would call it heteronormative. There’s something interesting and challenging about a time when there were no rules, and there was a downside to that too, but there weren’t really labels and rules and things. Everyone was making it up as they went along, and making up gay identity, which was pretty open, up for grabs.

SW: The section of the book that’s set in the seventies reads to me, if not always like a happy time, as a vibrant, exciting time. I’m wondering how you felt, emotionally, revisiting it.

BG: It was great. That’s how I got seduced almost into writing the book. First of all, we were all young, I was young, but mainly there was a taste and a visual thing to that period that came back to me really strongly, this kind of amber light and inky shadows and smell of dog poo everywhere — there was just something very specific. Also, writing about Howard, being back in that relationship with him that had been tamped down in memory over the years, though never forgotten certainly. To have him alive again — I mean, that was great. That was my feeling, that it was fun.

SW: You also make a point — I think it’s one of the most memorable lines in the book — of saying you’re “not nostalgic, just shocked.” Yet there is a lot of nostalgia about the seventies in New York. What do you make of that? I think we’ve talked about where the nostalgia comes from, but do you think it’s misplaced at all?

BG: I actually don’t think it’s misplaced. As I was saying, there’s something accurate about it. The thing is, the nostalgia stops. I’ve noticed that: People, for obvious reasons, are not nostalgic about AIDS in that period and, for obvious reasons, don’t want to go there. But you can’t have one without the other. One reason that we’re so nostalgic about it [the 1970s] is that it got flattened into history by AIDS and that all those people are dead. It could be great and there’d be a different culture if Mapplethorpe and Haring were alive, but we wouldn’t have the same pang about it.

SW: You also make clear that New York was a much less safe place back then. There’s a particular scene that sticks in my mind, where a man flashes a knife at you as he leaves your apartment.

BG: I remember someone doing that earlier when I was in college, and then in the Chelsea Hotel. So, yeah, knives were normal. Bashing was normal enough, although I didn’t quite encounter that — but you know, the threat of it. Also, on West Street, there was a bar a block from Christopher, and there was this phase, it was like a fad, where people would go by and shoot in the window, so there’d be bullet holes in the window. You’d be hanging out at this bar but being aware that you were sort of off to the side.

SW: I thought the section set in the eighties was very emotionally intense — in a good way. It was very well written. But really intense. I had to set it aside sometimes, because there was quite a bit of death, among other things. I remember a section of the book where you talk about anger and how you were just crackling with anger at some points. How hard was it to go back, emotionally, to that time?

BG: Very difficult. I got so seduced by writing about the seventies, writing about it in all its great colorful detail, that when I turned to the second half of the book all of a sudden I realized that I’d written myself into a corner, which I had to write also and then in detail, and graphically about the AIDS period. I didn’t particularly want to do that, but also discovered for better or worse that I had all those memories in this vault, intact, of St. Vincent’s Hospital and things, and I could really vividly see it all. It was really surprising to me. So, I did it. It was interesting to go through because it wasn’t all grim, in the sense it was the same people. You had a remarkable generation of these guys. They were funny. And still young, so there was a kind of weird erotic charge even to these AIDS wards. Also, they turned out to be, as a group, remarkably strong and noble facing death. I mean, everyone was so young —

SW: He was only thirty-four, right?

BG: Yeah.

SW: Which is incredible.

BG: Right. I never thought of myself as being someone who could even go to the hospital like that every night. I’d never had any experience like that. My parents were alive, everyone was alive. To see a whole generation and city face that was startling and a little, for all of us, what I think World War I [was like] when all those poets and Oxford types went off to fight and suddenly everyone was dying and you’re in this shocking situation.

SW: It seems to me that, when people talk about the eighties today, there are kind of two different versions of it. There are a lot of people who admire Ronald Reagan: For them, that decade has a golden glow to it. And then there’s everyone who remembers AIDS. What do you make of that very strange disjunction that exists with how we remember the eighties?

BG: It was an incredibly polarized time — definitely in terms of gay and straight and all that stuff. Also economic class. People were infatuated with the Reagans and money and power. There were all these black cars out and limousines and these restaurants — all that stuff. At the same time, there were more homeless people, and then you had people dying of AIDS. All this also you could see on the streets. You could see what was going on. You’d see sick people on the streets, who you’d known. It was split that way.

SW: Are you still in touch with Howard’s family?

BG: Yeah. Aaron, Howard’s nephew, made this documentary, Uncle Howard, that was at Sundance, so I’m definitely in touch with him. I’m in touch with his [Howard’s] mother. So, I am in touch.

SW: When you’re writing about real people and real events, and some of those people are still alive, you must feel some obligation to protect the rights and the privacy of those people. I’m wondering how you navigated that issue, of respecting the rights of the people involved, especially those who are still alive.

BG: Not many people are alive. It’s an unusual experience that way. You’re writing about people who would be alive but they’re not alive, so there weren’t that many actually. But yeah, I do think you need to be aware of people’s feelings. There’s a way of writing that unfortunately I have which is like putting on blinkers or something, and then I just don’t think about any of it and maybe I should. I guess I have the morality of a four-year-old when I write.

SW: Do you ever wonder how Howard would have reacted to the book? Did you think about it as you were writing, whether he would like it?

There was a way I felt: that I was carrying out this kind of obligation, almost, and that it would keep him alive.

BG: Yeah, always. After it was published, Sarah Lindemann, who’d been at high school with Howard at Exeter and then worked on some of his films, wrote me an e-mail that said, “You and I both know that Howard expected you to do this,” and that’s true. There was a sense of — I don’t know how else to say it, but he was a pretty aware creator and I was a writer. There was a way I felt: that I was carrying out this kind of obligation, almost, and that it would keep him alive.

SW: I think the book is actually a wonderful memorial to Howard. I’m guessing to some extent it’s revived interest in him. Would you say that some of that’s taking place?

BG: Yeah. Simultaneously and serendipitously, Aaron got the Burroughs movie back into Criterion print, so that documentary that Howard made is out and about. And then the Uncle Howard and then my thing. I think when I was writing the book I was really in my blinkered state, and it was really for me, and I didn’t show it to my agent or my publisher, and I didn’t really know if anyone would want to publish this book anyway. When it did then get published, I got e-mails from these guys saying, “I was afraid these memories were going to be lost.”

SW: You said you wrote the book in its entirety before showing it to anyone else, is that right?

BG: Yeah.

SW: So you didn’t do it on proposal — in other words, get a contract and write?

BG: No, it was like [playing] hookie or something, because I was working on this biography [about Rumi] that has taken eight years — it was in the middle of that that I did it, and I did it at night. It was like relaxation from working on the biography and all the research involved. It was a form of fun to be able to write without having to check every fact.

SW: You anticipated publishing it, though?

But I also wondered, Does anyone really want to read about gay guys dying of AIDS in the eighties? I did have that question.

BG: It was in my mind as a possibility, because how could it not be? But I also wondered, Does anyone really want to read about gay guys dying of AIDS in the eighties? I did have that question. It was also pretty personal. So I guess I tricked myself into not thinking too much about it [publication]. Also, the minute you get money for a book for which you’ve written a proposal, it’s kind of like you’ve committed yourself to a certain style, or to a publisher then saying, Well, maybe take the AIDS out? I just wanted to do it without compromising.

SW: What was it like going between a biography of Rumi and Smash Cut? Obviously very different projects.

BG: That’s why it worked for me to write them together, because they were so different. One’s completely personal, and the other is constructing a life from the thirteenth century.

SW: You’ve done other memoirs and other biographies. Do you prefer one or feel more comfortable with one or the other?

I have genre ADD.

BG: Not really. I have genre ADD. I’ve written different kinds of things. I sort of like that. I feel much more comfortable, I discovered immediately, doing interviews and going on tour talking about this memoir. It was easier, because there’s a way, when you’re talking about responsibility to the subject with Howard, there is responsibility to Flannery O’Connor or Rumi. It takes a while to frame them, to figure out how to talk about them. Whereas if you’re writing memoir, it’s really just like having a conversation about your life. There’s a casual authority that comes with writing about your life that you have to work for in biography.

SW: What are you reading now?

BG: I am reading many things, but I just finished reading, rereading, The Picture of Dorian Gray. I read it when I was like fifteen, and what I didn’t realize then and I do now is it’s like Stephen King. I hadn’t realized how gruesome it was, scary it was — all that kind of stuff, which is almost over the top and at the same time compelling intellectually. Then I’m reading — I have this big love of Knausgaard, which is corny but I have it. My boyfriend/partner/husband, Paul, is always complaining that I read too fast. He doesn’t believe I’m really reading. I’m now on the fifth volume of Knausgaard — suddenly it’s taking me ten minutes to get through two pages. The whole point is reading every word, and Knausgaard has a kind of detail fetish that I share.

SW: I know you’re very much in the thick of writing the Rumi biography: Have you thought at all about your next project?

BG: I started writing a novel, actually.