Interviews

Catching Up With The Eagles Prize Finalists: DW Gibson, Author Of The Edge Becomes Center

by Dan Sheehan

This fall marks the inaugural award of the Brooklyn Public Library’s Eagles Prize, recognizing “the best books of the past year and the authors who most embody Brooklyn’s ideals.” Nominations were made by the borough’s bookstores, librarians, and library supporters. The Library announced a shortlist of six authors–three for fiction, three for non-fiction–over the summer. The winners, chosen by a panel of local authors, will be announced later this month. In the lead-up to the announcement, we decided to ask the finalists a few questions.

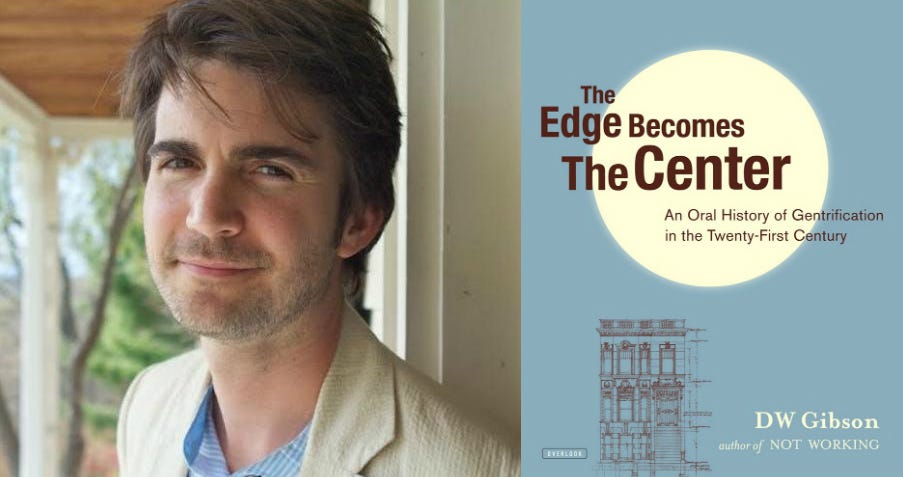

First up: DW Gibson, author of The Edge Becomes Center: An Oral History of Gentrification in the Twenty-First Century (The Overlook Press 2015).

Dan Sheehan: Why did you choose to write an oral history of this particular subject, gentrification? What did it allow you say that a more conventional structure would not?

DW Gibson: I feel like academia is awash in writing on gentrification; mostly theory, some case study. I wanted to find a way to make the subject meaningful and alive for the layman — or, more to the point, for those who are experiencing it firsthand. Oral history makes that possible because it gets away from the idea of one person explaining the phenomenon and plants us squarely inside the phenomenon. I was trying to curate and frame a big, complicated conversation. Through the experiences and perspectives of those who are living through the changes, the subject of gentrification becomes visceral. And I find that the quotidian is nearly always illuminating if you look at it closely enough.

DS: I was fascinated by the story of Jerry the Peddler, the squatter and squatters’ rights activist who has spent four decades enmeshed in this battleground. Can you tell us a little bit about his experiences?

DWG: Jerry is a really important part of the conversation about gentrification, and I think a lot of his story is spelled out in his chapter. There are two central points that I take from him:

The first is the very convincing argument that gentrification became part of the public conscientiousness in New York City after the police riots in Tompkins Square Park in July and August of 1988. Those events alerted the city to what was happening — and what was to come in the years to follow.

For the squatters it was about freedom, yes, but it was also about stewardship.

The other central point Jerry makes is that our conversation about gentrification is incorrectly framed as a conversation about property. This error makes sense considering our use of the word “gentrification,” tied, of course, to the idea of gentry. But ultimately the conversation in this book is not about property; it is about land. It is how we think about land and use land and share land as a city. Squatters get this because, for them, having a place to live is not about earning money to pay rent so that someone else takes care of the building. It is about being stewards of the building in which you live. It is about opening abandoned buildings that are going to waste and reviving those buildings. And that is, in large part, what unifies all the different communities of squatters that coexisted for so many years on the Lower East Side. Whether you were a hippy or a yippie or a punk, you learned to repair and improve and take care of the place where you lived. For the squatters it was about freedom, yes, but it was also about stewardship. And I think the city finally came to realize that over the course of a long, drawn out lawsuit with a large group of unified squatters, which eventually granted them ownership of 11 buildings.

DS: It was startling to read about the unconcealed racism of Ephraim — the Hasidic landlord in Brooklyn — as he described, in quite a matter-of-fact way, bribing or bullying black tenants out of their homes: “…every black person has a price. The average price for a black person here in Bed-Stuy is $30,000 dollars. Up over there in East New York, it’s $10,000 dollars. Everyone wants them to leave, not because we don’t like them, it’s just they’re messing up — they bring everything down.”

In your interactions with those who stood to profit financially from the current wave of gentrification, how pervasive was this attitude?

DWG: I would describe this as one of a handful of core threads throughout developer communities in New York City. But more to the point: in these communities there is, broadly speaking, a strong sense of “other.” Us vs. them. Tenants are the other. (Same goes for many tenant communities: landlords are other.) Class and race give shape and character to this otherness — implicitly if not directly. We have to face this reality. Once we do, we’ll find better ways to enforce the Fair Housing Act — and better ways to treat each other.

DS: Brooklyn has become, for New Yorkers at least, the area most associated with gentrification in the U.S. What do you think are the potential ramifications, long-term, of this massive demographic shift and foreign capital influx for the borough?

DWG: The prevailing effect will be that the borough becomes accessible to fewer and fewer people. Those who do maintain access will pay handsomely for it and those who can’t will need to find another place to go. The shopping, parks and cultural institutions will continue to attract tourists and the stories of the past will dwarf the pulse of the moment. People will come here less often to make art and more often to buy it.

DS: Many of those interviewed take issue with the word “gentrification,” finding it too nebulous and dismissive, too implicitly linked to land worth alone. You yourself, at the close of the book, state:

Gentrification is our word of choice because we have settled into the choice to let money frame our relationship to land. This abstract thing called money is, itself, in the process of abstracting land: a patch of earth where a building was constructed and used for work and shelter by one group of people has become an investment for another group of people in another neighborhood or state or country…

Do you think, at this point, a New York in which not all land is commodified is even possible?

Somewhere deep inside our capitalist souls — always yearning for the picket fence and driveway and privacy — is the understanding that some things must be shared.

DWG: No, I don’t. I think we would do very well to simply think of land as anything other than a commodity. Land as commodity is at the center of the American Dream. Unless we are redefining the American Dream, the idea of land as commodity isn’t going anywhere — this is clear. But what isn’t clear is: do we have the capacity to develop a stronger sense of shared space? I think that in this society we are capable of valuing commons and private property concurrently and equally. I think we are capable of understanding both stewardship and ownership. I like to think of our national parks system as the other half of the American Dream. Somewhere deep inside our capitalist souls — always yearning for the picket fence and driveway and privacy — is the understanding that some things must be shared. In New York City, we should better harness this innate understanding and allow for more gathering spaces, more spaces that aren’t completely indentured to capitalization.