essays

Exploring and Rebuilding Genres: Notes on Jo Walton

How does it shape a writer to analyze their own genre of choice? Though numerous writers can shift between reviews and fiction, the number known equally well as both novelists and critics is smaller. Head into the realm of contemporary science fiction and fantasy, and the number dwindles further. Thomas M. Disch’s 1998 The Dreams Our Stuff Is Made Of: How Science Fiction Conquered the World was, like the work of its author, alternately insightful and frustrating–Disch made some interesting points about science fiction and the larger culture, but also occasionally bogged down in Disch’s own feuds, including one with Ursula K. Le Guin. Reading it today can be a strange experience, as the insights and jabs grow increasingly at odds with one another as the book progressed.

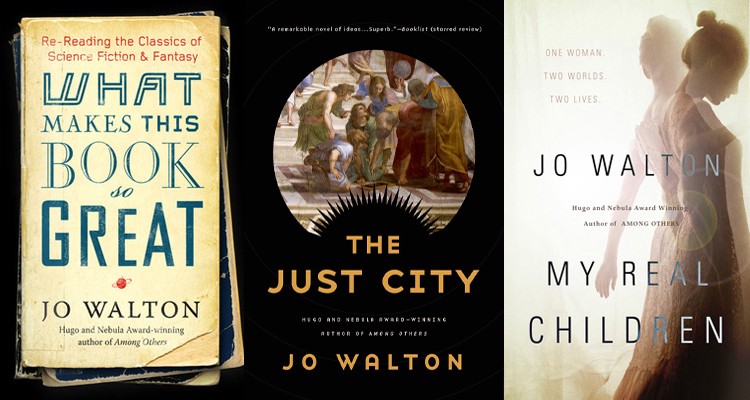

Last year brought with it Jo Walton’s What Makes This Book So Great, which compiled two and a half years’ worth of short columns that Walton had written for Tor.com. (Walton is still a regular contributor to the site.) Her focus was on fantasy and science fiction; in her introduction to the book, she notes that her “genre perspective” persisted for works that fell outside of those boundaries. As examples, she cited “how George Eliot should have single-handedly invented science fiction or wishing wistfully that A.S. Byatt had read Delany.” Reading it proves insightful, both for the boundaries of science fiction and fantasy and to get insight into Walton’s own creative process.

To date, Walton has released eleven novels; her twelfth is due out this summer. She’s received several major awards for her work, including a World Fantasy Award for 2004’s Tooth and Claw and a Nebula and Hugo for 2011’s Among Others. Some of Walton’s work foregrounds its supernatural or speculative elements; other works are more ambiguous. In her review of Among Others, Elizabeth Hand noted that “Walton does a deft job of balancing much of her tale upon a knife-edge where the reader is never quite sure whether the magic described is real or imagined.” Whether you read said novel as fantasy or realism, its bibliophilia and exploration of flawed familial dynamics make for a subtle, compelling read. It’s a novel that abounds with references to the science fiction and fantasy of the late 1970s, and it’s that community in which its protagonist immerses herself.

Walton also has a fondness for alternate histories, both as a writer and as a reader. (Her exploration of Terry Bisson’s Fire on the Mountain also contains some discussion of utopian novels, which will be relevant shortly.) Farthing, about a politically-charged murder and its investigation, began the Small Change trilogy. In the trilogy’s history, British aristocrats negotiated peace with Hitler early in the Second World War; by the time of the late 1940s, war between the Nazis and the Soviets rages on, and the worst aspects of British society appear to be hastening a shift into fascism. In Walton’s essay on Josephine Tey’s Brat Farrar, she notes that some of the quirks of Tey’s setting prompted her to envision the alternate timeline for Farthing:

This is a 1949 in which people cheerfully went on holiday in France eight years before and in which a thirteen year old running away seven years before could cross France and get work on a ship there — in 1941 and 1942? Surely not.

Last year’s My Real Children began with an institutionalized woman named Patricia Cowen as she looks back on her life, her memories adversely affected by her dementia. The novel begins as a straightforward look at her youth in the first half of the twentieth century; at a critical moment, a decision is made, and the novel follows the two timelines that result. To compare it to another novel of a life re-lived in 20th-century Britain, it’s Sliding Doors to the Groundhog Day of Kate Atkinson’s Life After Life. (Walton has cited Ken Grimwood’s Replay as one of the stories she feels that it resembles most.) There’s plenty in My Real Children that impresses, including the subtle differences between each of the two timelines.

It’s also a powerfully sad book: dementia claims Patricia in each one, and by the end of the novel, the state in which she exists is one of confusion, unsure of which set of memories is real. But at the same time, it’s unexpectedly optimistic: neither of the timelines in which she lives precisely lines up with our own. It’s the butterfly effect in practice, perhaps: that the outcome of one phone call might lead the world in a wildly different direction. For all that the novel makes certain outcomes inescapable, it also takes as a given that one ordinary human life can effect change on a grand scale.

The relative realism of much of her recent work sits in sharp contrast to her latest novel, The Just City. Throughout What Makes This Book So Great, Walton moves through a variety of styles and approaches to genre. Samuel R. Delany is frequently discussed, and there are also long stretches dedicated to Lois McMaster Bujold’s galaxy-spanning Vorkosigan novels and stories and Steven Brust’s works set in Dragaera. (Walton describes it as “[looking] like fantasy but there’s no doubt in my mind that it’s science fiction underneath.”) Given this omnivorousness with respect to genre shadings, it’s tempting to see The Just City as a kind of end run around the boundaries that expectations of styles and subgenres can establish.

What makes The Just City a particularly intriguing read in light of all of that, then, is that it isn’t just an idiosyncratic work blending science fiction and fantasy–it’s a work by someone who knows the ins and outs of both genres. Though for all of that, it’s also proudly in certain traditions: specifically, the idea of a seemingly utopian society with a flaw at its heart. The way in which that society emerges is unique, however: Greek gods decide to set up Plato’s Republic in the distant past, and summon willing participants from throughout time to govern it.

Walton has written that this is the first book in a trilogy, and it’s a particularly unconventional beginning: The Just City’s narrative is one that by necessity encompasses everything from intrigue among the gods to Socrates communicating to robots from the future to the logistics of setting up a utopian society. It’s unabashedly philosophical science fantasy, and suggests that Walton is staking out a very particular corner of the genre as her own. For all that The Just City is staking out its space with Big Ideas and a narrative that both spans time and occasionally exists outside of it, Walton roots much of it in recognizable psychology. It’s a quality that helps the book hold together–grounded characters accepting an eminently fantastical premise goes a long way.

The essay that closes What Makes This Book So Great is titled “Literary criticism vs. talking about books.” In it, Walton notes that she doesn’t consider herself a critic, but does explore some of the larger issues that her explorations of novels and stories have sparked, noting in particular “a divide within SF between literary and popular” that she notes is “drawn in a very strange way.” However Walton views these pieces, they do a fine job of re-opening discussion on some works, pointing readers towards others that may be unfamiliar, and providing illuminating looks at her own fiction. As author and reader, Walton’s contributions on both sides of the divide are helping expand and shape the genres in which they’re found.