essays

Five Fusty Excerpts from Archaic “Nonfiction” Texts

by Julia Elliott

Eons ago in grad school, I spent obscene amounts of time reading Medieval and Renaissance lit, writing obscure essays on gender politics: women as angelic air bodies in the erotic poetry of John Donne, monstrous pregnancies in Jacobean drama, the serpentine “nether parts” of Sin in Paradise Lost. During my scholarly period (I’m now a fiction writer), I read a slew secondary texts on theology, monsters, witchcraft, medicine, madness, anatomy theaters, gynecology, obstetrics, and other riveting subjects.

Many of these fusty old books, including the medical texts, blur the boundaries between realism and fabulism, science and fiction, Earth and Heaven and Hell. In Bald’s Leechbook (9th Century), you can find cough syrup recipes along with ingredients for salves that ward off “nocturnal goblin visitors.”

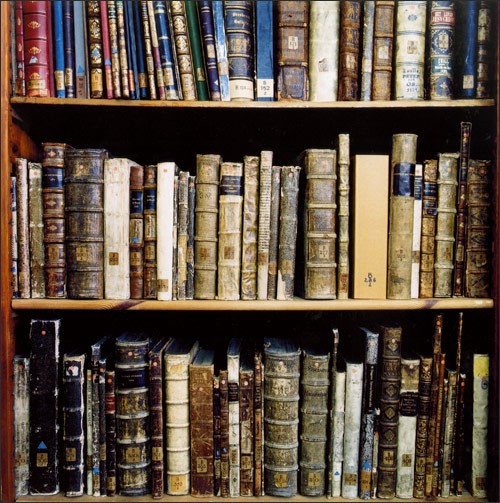

Here are five fascinating samples from archaic “non-fiction” texts, the originals of which would’ve been bound in goatskin, shaved calfskin, or maybe even “uterine vellum” (parchment made from the silky hides of stillborn animals).

The Book of Rota, 13th Century

The Trotula, a three-volume 12th century Latin text on women’s health, derives from the name of Trota of Salerno, a real physician who supposedly wrote medical texts. In Medieval Europe, “Trotula” personified female gynecological and obstetric knowledge, and several Middle English works claim to be translations of the great Trota’s original words. This excerpt from The Book of Rota explains how to determine whether infertility is the man or the woman’s fault:

Take a lytyll earthen pott newe and put therin the mans uryn and cast therto an handfull of bran and stere it fast with a sticke about and take another newe erthen pott and put therin the womans uryne and put bran therto and ster it as the other, and let it stande so nine days or ten and loke than in whether pott that yow fynde wormes in. Ther ys the defaute that is baren, be yt the man or the woman, for the baren wyll be full of wormes. The vessel that the baren uryn is in wyll stynke.

“Treatise on the Angels,” Summa Theologica, Thomas Aquinas, 1265–1274

Thomas Aquinas, a Dominican friar and scholastic theologian, reputedly levitated during rap sessions with the Virgin Mary. His three-volume Latin tome covers theological subjects with the mind-numbing thoroughness of a legal document. Although he didn’t calculate the number of angels that “can dance on the head of a pin,” he came close in his “Treatise on the Angels,” which discusses all things angelic, from the way spiritual creatures sport air-bodies when hanging out on Earth to the way they chat with each other via telepathy. Aquinas also gives us the dirt on angelic sin and demons. In this English translation of “Reply to Objection 6” or “Whether the angels exercise functions of life in the bodies assumed,” he answers the burning question: can an incubus knock up a mortal woman?

Still if some are occasionally begotten from demons, it is not from the seed of such demons, nor from their assumed bodies, but from the seed of men taken for the purpose; as when the demon assumes first the form of a woman, and afterwards of a man; just as they take the seed of other things for other generating purposes . . . , so that the person born is not the child of a demon, but of a man.

Venerabilis Agnetis Blannbekin, 13th/14th Century

For visionary writing from the Middle Ages, you can’t beat female mystics, women who hid out in convents and hermitages and received visions from Christ, the Virgin Mary, angels, and the occasional trickster demon. These mystics either wrote their own accounts or described their experiences to scribes. Some of them took the whole nun-as-the-bride-of-Christ thing to heart, eroticizing the spiritual marriage and obsessing over Jesus’s body — fetishizing his foreskin, for example. Catherine of Sienna claimed that when she and Jesus tied the knot, he slipped a ring made from his own circumcised foreskin onto her finger. Bridget of Sweden and Agnes Blannbekin both described the pleasures of eating the “holy prepuce.” Blannbekin dictated her account to an anonymous confessor, and this excerpt is from an English translation of a German version of the original Latin:

And behold, soon she felt with the greatest sweetness on her tongue a little piece of skin alike the skin of an egg, which she swallowed. After she had swallowed it, she again felt the little skin on her tongue with sweetness as before, and again she swallowed it. And this happened to her about a hundred times. And when she felt it so frequently, she was tempted to touch it with her finger. And when she wanted to do so, that little skin went down her throat on its own. And it was told to her that the foreskin was resurrected with the Lord on the day of resurrection. And so great was the sweetness of tasting that little skin that she felt in all [her] limbs and parts of the limbs a sweet transformation.

Ambroise Paré, Des Monstres et prodiges, 1573

Ambroise Paré, a French Barber Surgeon, anatomist, and forensic pathologist, attended the bodies of Kings and developed novel techniques for treating battle wounds. Despite his practical know-how, he wrote Des Monstres et prodiges, a sensationalist “science” text that describes wondrous creatures of the earth, putting rhinos and sea crabs right alongside freaks like “a marine monster resembling a Bishop in his pontifical garments.” A significant number of Paré’s monsters come from women’s bodies, reflecting early modern anxiety about female reproductive anatomy. Back then, women didn’t ovulate, for example, but ejected a cold, clammy “seed,” an inert glop of slime that men ignited with their own fiery spunk to forge a viable embryo. The wrong combo or quantity of seed could cause a host of issues, and imagination could also affect a fetus: a pregnant woman startled by a frog might end up with a frog-faced child. Eating the wrong foods could cause “monstrosities,” as could the mischief of demons and sorcerers. The following description of a monstrous birth is from the 19th century English translation, On Monsters and Marvels:

. . . with great effort she delivered a formless mass of flesh, having on each side handles the length of an arm, which moved and had life, like sponges. Afterward there came out of her womb a monster having a hooked nose, a long neck, sparkling eyes, a pointed tail, and very active feet. . . . [H]e began to hum loudly and fill the whole chamber with whistlings, running here and there to hide himself, upon which [monster] the women threw themselves and suffocated him with pillows. In the end, the poor woman, completely exhausted and torn, gave birth to a male child so racked and tormented by this monster that he died as soon as he had received baptism.

The Anatomy of Melancholy, Democritus Junior, aka Robert Burton, 1621

In his two-volume study, proto-psychologist Robert Burton explores the mental effects of the darkest bodily humor — black bile — an excess of which supposedly caused melancholy.

Too much black bile could turn a person into a mopey poet who sulked alone in dark forests, but melancholy could also wax into illnesses like lycanthropia, or “Wolf-madness, when men run howling bout graves and fields in the night.” In his exhaustive study, Burton explores the causes and cures of various forms of melancholy, devoting his third partition to “Love-Melancholy.” This section not only discusses causes and cures, but contains some vivid (and uncharitable) descriptions of love-sick men and women. Here’s his take on old guys in love:

How many decrepit, hoary, harsh, writhen, bursten-bellied, crooked, toothless, bald , blear-eyed, impotent, rotten, old men shall you see flickering in every place! One gets him a young wife, another a courtisan, and when he can scarce lift his leg over a sill, and hath one foot already in Charon’s boat, when he hath the trembling in his joints, the gout in his feet, a perpetual rheum in his head, a continuate cough, his sight fails him, thick of hearing, his breath sinks, all his moisture is dried up and gone, may not spit from him, a very child again, that cannot dress himself, or cut his own meat, yet he will be dreaming of, and honing after wenches, what can be more unseemly?

***Burton’s descriptions of “unseemly” women are even more ruthless.

Sources (in order of appearance):

The Book of Rota. Women’s Writing in Middle English. Ed. Alexandra Barratt. London: Longman, 1992: 38.

Aquinas, Thomas. Summa Theologica, Volume 1. Hayes Barton Press, 1862: 488.

Wiethaus, Ulrike. Agnes Blannbekin, Viennese Beguine: Life and Revelations. The Library of Medieval Women. Ed. Jane Chance. DS Brewer, 2012: 35.

Paré, Ambroise. On Monsters and Marvels. Trans. Janis L. Pallister. Chicago: U of Chicago Press, 1982: 58

Burton, Robert. The Anatomy of Melancholy, Volume 2. Kila: Kessinger Publishing Company, 1991: 657