interviews

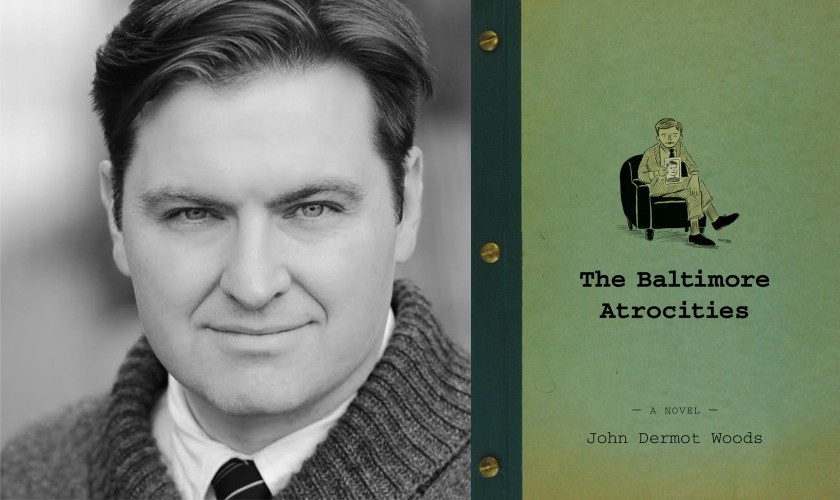

INTERVIEW: John Dermot Woods, author of The Baltimore Atrocities

by Guy Benjamin Brookshire

John Dermot Woods has been illustrating his writing and drawing comics for more than fifteen years. In an era when “comics” and “graphic novels” have demanded a place at the table of literature, perhaps no one alive more deserves the seat.

His latest work, The Baltimore Atrocities, is a mesmerizing and bewildering descent into the collective irrational where civic failure meets personal flaws. In a world we wish we didn’t recognize, murders and self-destruction attend mystery and conspiracy, visited upon characters that might appear to inhabit dark fables for a moment or two before we taste the unmistakable tang of psychological and sociological truth.

Guy Brookshire: What window do you look out of most often? What is on the inside of the window, and what is on the outside of the window?

John Dermot Woods: Until recently it was the top floor of my house in Brooklyn, right over the top of my drawing table (or beside my computer). Outside I can see the roofs on north side of Saint Marks Ave and One Hanson Place, the tallest building in the borough. And the Barclays Center, soon to be the proud home of the New York Islanders.

GB: “Until recently…” where are you now?

JDW: I’m the visiting writer at Saint Lawrence University in Canton, NY. The exact opposite pole of New York State, not far from Ottawa and Montreal. I’ve been told surviving winters here is a heroic feat, but the summer and fall I’ve experienced so far have tested my mettle in no way. Lots of rivers and mountains and orange leaves. Not a bad place to spend some time.

GB: I think of you as a writer whose writing is in the medium of comics. A kind of artist. Like a playwright. You write comics as you might write plays. Tell me how I’m wrong.

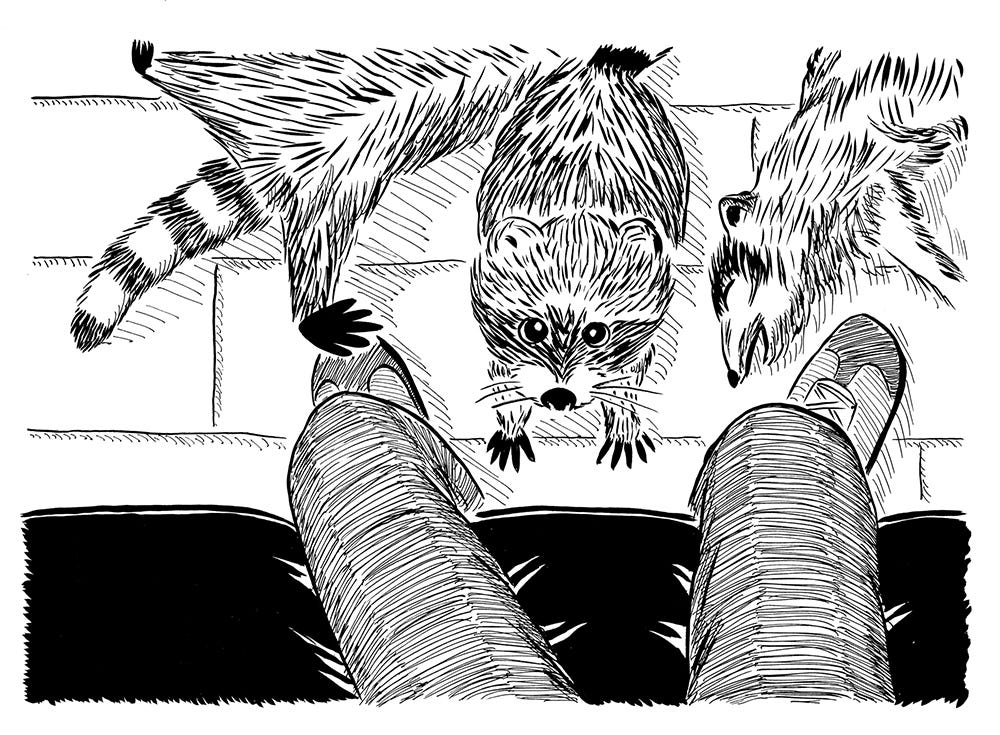

JDW: Having trouble thinking of how you’re right! I guess the fundamental difference is that I draw comics more than I write them. And that is definitely the verb that defines my experience. Comics are image driven. As much as most comics use words and images, the words are definitely in service of the images. Especially in my work. To compare it to another medium: it’s the rare film that is fundamentally constructed around its sound editing (although it’s important and essential). When comics use words (like mine do) they’re important, but they’re not where it begins or the fundamental aspect of its composition.

GB: I’m surprised to hear you say that. I think I understand about the sound editing, but when I’m watching a film, I’m thinking of the script/screenplay, thinking often how far or close to someone’s vision what I see is…and I see you as sort of a director of your own films. I know you have worked on screenplays…is the process similar?

JDW: Oh, I see You’re talking about actually using a script. No, I don’t script my comics. Sometimes it’ll begin with some writing, some prose. But then I draw. Usually a series of thumbnails and rough sketches. When I work with Lincoln Michel, he’ll do some scripting, but even that is rough, and basically a guideline for us to create thumbnail pages. I use those thumbnails to draw from.

GB: So you see the comic before you write it?

JDW: You don’t really “write” a comic. There’s writing involved, but it’s really a process of drawing. So, yeah, it usually begins with an act of drawing, not writing. But I think the drawing may be more similar to this idea of writing than you’d imagine. It’s not as if I see the whole thing in my head and then capture it with my pencil. I work it out with my drawings just the way we can work things out with our words.

GB: Do you want people to know anything about your life before they read your work, or do you think that knowing anything about your life and the way you live would help people appreciate your work more deeply, more completely…more favorably in a critical sense?

JDW: No, I’m thinking my biographical details aren’t going to do a lot to engage people in my work. No one wants to hear about another pre-pubescent chess prodigy who had to give it all up when the demands of his medical residency coupled with the stresses of his emotionally turbulent but surprisingly fruitful adolescent love life became too great. I actually wrote this all down in my word processor diary. But, that was before the internet, so who the hell knows where that ended up?

GB: I think people would be interested in a “surprisingly fruitful adolescent love life.” I am. I find the chess prodigy thing harder to believe than the medical residency, by the way.

JDW: I don’t know, there are a lot of little episodes I could relate. Maybe one day I’ll write a TV show about it.

GB: Are you an Irish-American writer? Are you an Irish-American comics-artist?

JDW: Yes, my work constantly defers pure expressions of human emotion with smug irony, yet is centered around a maudlin sense of meaning as defined by surviving tragedy. And the generic nature of my first and last name has forced me into the embarrassing practice of signing my work with my Irish-y (yet Anglicized) middle name: “Dermot.”

GB: Do you think you have inherited, perhaps genetically, a special relationship to the English language by virtue of your Irishness?

JDW: Yes, but it’s definitely a nurture over nature situation. Other countries put political leaders on their currency. The Irish adorn their money with porn writers and decadent poets. It’s a country that cares a lot about words. At my dinner table growing up, surrounded by people either surely or ostensibly descended from those people, we cared a lot of about words. We used a lot of them and wrangled over the meaning of each one. (And my dad was a criminal defense attorney, so…)

GB: Did your father bring his work home? Were you often cross-examined? I ask because there is often both a sense of mystery and officiousness, of procedure and transgression in your work. Maybe an idea that words and procedure can’t make bad things go away, but you can try. That people are flawed but deserve a dignity they seldom get to enjoy.

JDW: He never brought a client to the dinner table, but he talked about the courtroom a lot. My father was less likely to cross-examine me than encourage me to be the cross-examiner. (Somehow neither my brother, my sister, nor I ended up in law school.) And, I think you’re right. I have a hard time admitting that language has limits. Ben, and I think you and I are the same here, and look where our conversations end up. But, my father is definitely the guy who imbued this idea dignity should be offered to everyone, especially the flawed, the very flawed. Maybe that happens in my writing, I don’t know.

GB: Do you have to write with the explicit project of representing a group to claim to be a hyphenated artist?

JDW: Nope. You can have that yoke foisted upon you by birth and the cultural habits of your parents. Eighteen years of Sunday afternoons with the family hi-fi tuned into WFUV’s Irish folk show can really re-wire your brain.

GB: Is it something you choose to celebrate, or is it inescapable?

JDW: Can’t beat ’em, join ’em, Ben. I earnestly enjoy Saint Patrick’s Day, the low holy day when Irish-Americans gather to minstrelize the proud culture of their motherland. (I really do enjoy Saint Paddy’s Day.)

GB: I don’t personally know anyone who connects more people than you do. You don’t simply know people, you connect them. Is this a character trait, or is based on a philosophy you have adopted?

JDW: I guess the former. I’m fundamentally self-conscious and shy, like a lot of people, but I do actively fight against that, and feel that there’s virtue in doing so. In the art world, I see a lot of anti-social behavior that is encouraged and lauded and I think that’s a breach of, I don’t know, the social contract.

GB: Do you think community is essential for writers and artists? Is that community essential to you? Or do you think you would pursue the virtue of fighting against shyness in any vocation?

JDW: Yes, it’s essential and yes, I hope I’d pursue that virtue in vocation. I think you have to. Community is inherent to writing in that we write to be read. Perhaps in the diarist community, it’s less essential. But those of us who intend our work for audiences must be aware and actively part of some kind of community. There is usually a practical aspect to all vocations, a service, which means we are working for others. The more we understand that, the better we can do our jobs.

GB: That makes art sound like a fundamentally ethical project. Does an artist fail if he creates unethical art?

JDW: Isn’t the social act of creating art for an audience an ethical undertaking? I don’t think I’d be able to judge any art as unethical based on its content.

GB: Do you feel young?

JDW: Yes, because I make a habit of spending most of my time with people born in the exact same year that I was (present company included). We did a book tour based on this very theme last year, didn’t we? There’s something reassuring about the company of thirty-six year olds. We’re young enough that we’re not yet subject to recommended prostate exams (although it can’t hurt), but we’re old enough that a few Genny Cream Ales and two or three plays of “Kennel District” and we’re sleeping like babies by midnight.

GB: Do you think 36 is younger than it used to be?

JDW: Yes. I often hear people bemoan the “prolonged adolescence” that our culture has engendered for various reasons. One of the real advantages, though, is that we no longer feel pressure to define ourselves early and forever. We can keep figuring out what it is we are doing or to what we want to dedicate ourselves, and that’s okay.