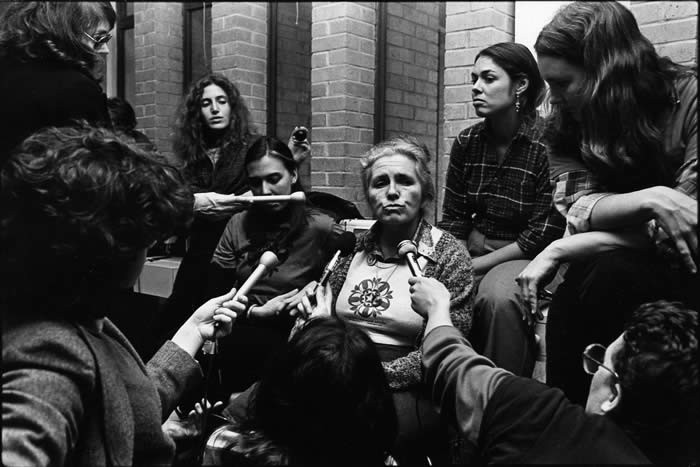

interviews

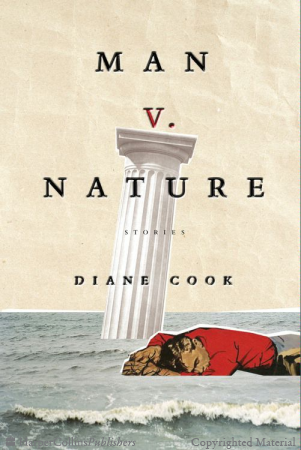

“It’s Us V. Us”: An Interview with Diane Cook, author of Man V. Nature

I had the chance to talk to my friend Diane Cook about her debut collection, Man V. Nature. Her stories are broadcasts from a world at once tender and terrifying. Each one grapples with questions of survival and how to be human in a universe turned upside down. Her book is like a memory from a place you’re almost certain you’ve never visited.

We chatted over email about Leelee Sobieski, writing prompts, and the psychological violence of endings.

Hilary Leichter: Your book has quiet apocalypses and crowded apocalypses. In stories like “It’s Coming,” or “A Wanted Man,” the reader is swept forward on a wave of ensemble choreography, a mass of humanity tumbling forward. The crowds feel like big, wonderful characters themselves. How do you keep track of an unruly mob on the page?

Diane Cook: I love to write a crowd. I like it best when it kind of throbs and swells like one organism. Because crowds are kind of this other life form. Or they’re a new form of us. There is a scene from the story “It’s Coming” where the main characters head to the roof of a building to escape a threat. From the roof they see the rest of the city running to escape that threat too. I imagined and wrote it be cinematic, sweeping, the crowd compelled and relentless, a bit like water flowing. I was probably thinking a little about that scene from The Last Unicorn where all the unicorns are released from the sea after The Red Bull is defeated. And I would have been thinking about mass movements or migrations. Herds of wildebeests across the Serengeti. Those helicopter shots (or I guess drones these days) showing just immense landscapes teeming with movement. Even real images or imagined ones of human mass movements, migrations, forced marches. These are images or feelings I return to often. Mass movement across land is an image and idea I think about often.

HL: Why write about the end of the world?

DC: The end of the world is just one kind of end and any kind of end tells us about ourselves. I’ve been thinking a lot about Deep Impact lately. I love Deep Impact because not everyone is saved. And when not everyone is saved, people’s decisions matter more. I like to watch the scene where everyone is fleeing, and then when the impact occurs. The scene where the parents give the baby to the daughter, and force her to flee without them. It’s Leelee Sobieski. I don’t know anything about acting but I think she’s amazing in this moment. Her confusion dawning to understanding then dissolving into a new kind of confusion is really devastating. I just made myself cry picturing it. I don’t revel in people’s misery, but there is this thing about the dawning moment, when a person realizes what is happening. I think we have that dawning with everything even — and maybe especially — small things. A moment we realize what is happening to us, what is pushing upon us, what this thing is, what is ending. I like to have some disasters, apocalypes or smaller personal disasters in my stories, but not really the heroics. I want to highlight and explore these moments of dawning.

HL: In “It’s Coming,” a group of executives are chased by an unknown beast — or is it a beast? We never quite see around the corner and catch a glimpse of what, exactly, they’re running from. There’s a similarly veiled evil in “Marrying Up,” festering just outside the narrator’s house. These feel like violent secrets the book is keeping from us. Like these are kinds of calamities that our pre-apocalypse brains don’t yet have the language to hear or see. Do you have names and faces for all of the unnamed beasts and monsters in your book, written down in some scary folder? Will they come up in your fiction again?

DC: I like that you imagine a compendium of monsters. I should write one, but I’m sure one exists by someone very creative who can draw. I like when things aren’t named. I had one reader ask if the threat in “It’s Coming” could be specific, something like a gunman. But then you’ve got a story about a gunman and then what? Then everything is done for the reader. Maybe you wonder, Why is the gunman doing this? But, I’m not often interested in why evil is done. I’m interested in what people decide in the face of evil. Or in the face of anything. I like when things go unnamed because I think a reader is better at filling in those blanks than I can be sometimes. I could have been very specific about certain stories, about certain threats in the stories. I certainly had images in mind, and had imagined a whole world I could have described. But when people read a story they introduce themselves to slightly new and different characters and worlds than I made. They’re bringing their own take on everything I’ve put before them.

HL: That reminds me of The Texas Chain Saw Massacre. There is a lot of imagined violence in that film. People see it, and afterwards, they swear that they are watching extreme gore. For many scenes in the film, it’s only a series of images that suggest gore, rather than gory images. I like the way you’re applying this idea to language, that the right words and sentences can create something terrifying in absentia.

DC: I certainly know where the monsters are in these stories, but a reader is going to have a much more interesting sense of that than I do, or at least a more personal one. The stories are for them to interact with and fill in with their own selves and imaginations. I think that’s what stories are best for. Maybe they’re like coloring books. Perfect form for what they are but the reader is needed to give it something more. And no two readers will color it the same.

HL: I want to hear more about the visible violence in your book. It’s gut-punch good. How do you write scenes with literal punches to guts? And still manage to somehow make those punches feel tender?

DC: The violence in the stories often comes from a deep and unanswered need, not out of a desire to harm. So many of the characters want to connect with others. The situations feel extreme though, and so perhaps their contact with people must have an extreme nature. But the need and the yearning is still felt. I think of a character like Gabby from “Girl on Girl” who is young and in turmoil and doesn’t have an expression for her needs and desires and so they come out in violence.

HL: Gabby’s violence is like a note left in a locker, or an ignored invitation to a sleepover. There is so much need there.

DC: And like Gary in “The Way the End of Days Should Be” who you sense is holding all the world’s loneliness in him but also happens to be the unofficial bodyguard for the solitary narrator. His violence is reluctant and his need to connect is bubbling.

HL: For every unnamed danger in your book, there are dangers that are fatally familiar. In “It’s Coming,” the refrain of “We are executives” felt like an echo of the financial crisis. For me, they might as well have been chanting “Too big to fail.” Do you start your stories somewhere nestled in reality, and then work your way towards the fantastic? Or do you write yourself a yellow brick road from Oz, home to Kansas?

DC: I guess in a way I do write myself back closer to a world the reader knows. I try to trim out really excessive things, the things that might allow the world building to take over from the fact that this is a story about people and a moment in their lives. In early stages, I overwrite the world so that I can understand it and then in revision I try to rein it in. The world can get cluttered. You don’t want to notice too much when you’re reading.

At least for this book, I tended to give myself rules or scenarios just so I could start. For “It’s Coming,” I was reading The Bloody Chamber. I was at a residency. I had time to play. I thought, I want to write a story that is full or gore and the word prick. Of course no story ends up only embodying the vague ideas you had when you started. The story holds so much more to it than starter rules or desires for it. But, as you may have noticed, there is a lot of gore in it. And the word prick. Twice. Which I think counts as a lot in a brief literary short story.

HL: It counts as a whole lot. I think this is one of the greatest writing constraints of all time.

DC: It was a fun constraint, that’s for sure. As for how the story shapes itself and why, I know I’m nodding to many familiar things, but I’m not doing that on purpose. I’m letting the story and my imagination take me somewhere, at least when I’m generating it. In the same way you couldn’t help but imagine “Too Big to Fail,” there were things I couldn’t help but imagine. But I didn’t want the story to be about any of that. I just wanted the story to be about threat, both familiar and strange. Anticipated but not believed in and not taken seriously, until it’s too late. And that can be a lot of things.

HL: In “Somebody’s Baby,” an anonymous man steals infants from the women who live on what seems to be an otherwise quiet, suburban street. I was struck by this killer question you ask in the story: “If you could suddenly get back everything you’d already said goodbye to, would you want it?” It feels like a fourth wall teardown, a challenge to the reader, a prompt for remaking the world, our individual worlds, or even a writing prompt. It’s a kind of fearsome nostalgia. Characters in your book lose their friends, their coworkers, their babies, their husbands, their fortunes, their families. In the world of your book, is nostalgia a dangerous thing? What’s the remedy?

DC: That would be a fun (or not fun) prompt: Write something you’ve lost back into your life.

Nostalgia is always a little dangerous, no? I mean, I guess it has to do with your temperament and relationship to it. But as you yearn and pine and think in the past, what are you really hoping for? What was? That thing forever? Endings can be psychologically violent. At the very least they send us into a bewildered state. Something of what we knew is over and now ahead is an unknown. We’re rarely ready for it. I think the characters in the book often instigate their own traumatic endings. Their worlds barrel on, but it is so hard to let go. I think the stories have something to say about the characters, newly bewildered, but also about those barreling worlds.

HL: Your book has men stranded in boats. Stranded in floating houses. Stranded in forests, on the rooftops of office buildings. I very much want to ask you the classic, stranded-on-a-desert island question: What book would you want to be stuck reading? But also, what book would you want to be stuck writing?

DC: There are a lot of books I return to again and again. Walden is one, and many other nature writing texts. Volumes of poetry. But if I were stuck I think I’d want a story to get lost in. Possibility rather than philosophy. Maybe a collected stories from Flannery O’Conner or Alice Munro or Steven Milhauser or Cheever. But doesn’t that feel a little like cheating?

HL: A little, but it’s a good cheat.

DC: I felt like I could read Dept. of Speculation a hundred more times. That book meant the most to me this year.

HL: I loved that book. I dog-eared that book like nobody’s business.

DC: It was so good. If it were the only book I had, I could get wrapped up in the story, but, if the story started to get tired I could read each little vignette like its own small book. That feels like a nice challenge. And if I were stranded on a desert island I think I’d want some other challenge to distract me from the challenge of plain old survival. As for a book to be stuck writing, I would never want to be stuck writing a book.

HL: There are so many babies in your book. There are so many possibilities of babies, and absences of babies. And then there’s a really huge baby in “Marrying Up,” so huge and strong and terrific. Is there something about writing about the end of the world that requires a nod to life’s beginnings? Are babies and apocalypses literary soul mates?

DC: I think every bigger ending in the book nods at a smaller, more personal one. Or some moment when your world and priorities get blown up and change, and when the ways you would have behaved earlier in your life must be interrogated. The baby stories have undercurrents of a new sense of responsibility. The mothers have to think about their children first, but they themselves are also in a kind of danger or under a kind of pressure or maybe just new and naive about it all. I’m curious about how extreme situations change us, or don’t. I think the babies in the stories — or the idea of the babies — put pressure on their mothers. It’s what those mothers do under that pressure that I’m interested in.

HL: I love that your narrators push back against the extreme parameters of your stories. They don’t always sit still and accept the rules you’ve created. They don’t want to move on from their marriages, or give up their children, or invite hoards of strangers into their homes, and yet, you’re telling them they must. They’re rebellious, and they don’t want to behave. I’m thinking of Stan and Susan in “It’s Coming,” having sex in the halls of their office, in front of all of their colleagues, while being chased to their deaths.

DC: I love Stan and Susan. They are two of my favorite characters. They do what they want in the story, but I understand that they haven’t always.

HL: They hold fast to the things that make them human, despite circumstances, and that’s a really beautiful kind of stubbornness.

DC: I think a lot of the characters feel put upon. Perhaps the rules of their worlds put pressure on them. The must make concessions to these rules and aren’t very happy about it because it doesn’t feel quite natural to them. They can’t adapt even though others have. The rules are the burden or some expectation from the big or small society surrounding the characters. I like that you call it a beautiful stubbornness, because I think the characters each question it at some point. Why can’t they be like everyone else? Even as they are pushing against it, even as they are feeling like they’re right. Honestly, I never considered they would go gracefully along with these worlds. I don’t know what the story would be if so. If I remember correctly, an earlier version of “The Mast Year,” had Jane trying to be much more game, and maybe even flattered by it all.

HL: Jane is experiencing an incredible winning streak in the “The Mast Year,” and everyone in her community (in the world?) comes to break off a piece for themselves. By the second page of the story, it feels like people are literally popping out of the woodwork to bask in her good fortune.

DC: Yes, it’s incredibly overwhelming and invasive. As I kept working on the story the pressure of the outside grew more intense and wild. And so, whatever good nature she might have had in earlier drafts dissipated. Almost as though the longer the story existed and got tinkered with the more tired she got, and the façade dropped and she was allowed to just be herself and to admit what a burden this all was. She tries to please but it is more muted and whatever she offers to others is really in service of getting them to leave. Meaning, it’s self-serving. Don’t we go along with things — often — because it is easier to, and the burden will feel lighter and shorter if we adapt to the things that feel heavy?

HL: Absolutely. It’s always harder to be Stan and Susan.

DC: Poor Stan and Susan. I really have so much affection for them.

HL: One of your stories has a major twist ending. To me, it felt perfectly executed. It vibrates. Can you talk a little bit about the experience of writing a spoiler-worthy moment?

DC: Ha, no because that would spoil it!

HL: Don’t spoil it!

DC: I’ll just say that some ingenious notes from excellent readers caused a light to go off in my head. Like I stripped a layer of sand and there was a a full and perfect stegosaurus skeleton or whatever. The story led me in a direction and then let me discover this new cool thing there. The story kind of made it. I really love that about writing. At least, writing when you’re open to surprises. I was especially heartened that this really important surprise came about in revision. Revision is hard for me. I mean, it’s a struggle whereas the initial writing is pure joy. I used to worry about the stories losing an electric or inspired feeling because I’m being so thoughtful about everything. I don’t think they do, but it’s a worry when you’re fine tooth combing everything. But in revising this book I’ve had a lot of electric and surprising moments. So it makes me happy that I had energy behind the stories through the whole process.

HL: The competitive, “versus” structure of your title sets up each of these stories as potential face-offs, or cage-matches. We have bouts between neighboring houses, high school girls, and abandoned boys in a forest. There are almost never any winners. Is the end of the world a fight to the finish? Fill in the blank: Diane Cook V. _____.

DC: Going back to Deep Impact (my sincerest apologies) —

HL: Never apologize for Deep Impact.

DC: — I think the sacrifices the characters make for others and their loved ones are moving. But we do get it immediately. Téa Leoni gives up her helicopter spot because she needs to heal with her dad. The parents are giving their children a chance at a life they’ve already lived. All around them are people angrily honking, yelling, fighting. But we don’t get those stories. I always felt those people (in any kind of disaster movie) are portrayed in a negative light, like, Look how selfish and self-serving. We’re not supposed to be interested in those stories. But I am. Those people are also trying to save something they think is important: whether that is their family, loved ones, or their own life. Maybe we are turned off because they’re doing it without grace. But, I think they’re the most like us; they’re not the stars and they’re not the sacrificing heroes. And I’m interested in that. There is a line in the story “The Not-Needed Forest” that to me says a lot about the spirit with which some of the characters in the book approach whatever their end is. Survivors always say yes. Meaning, that survival of anything comes down to decisions and willingness. I don’t know about a fight, but I think we make these small decisions everyday. We’re trying. But in a life without large scale conflict, or some extreme foe, if we fight anyone it’s often ourselves or the ones we love, in a way that breaks us up, invites tiny ends to life as we knew it. It’s Us V. Us.

***

Electric Literature published Diane Cook’s story “Man V. Nature” last week on our weekly fiction site, Recommended Reading. Read it here.