essays

Jeff VanderMeer’s Epic List of Favorite Books Read in 2015

In 2015, my reading felt futile in the sense that for the first time in a few years I felt overwhelmed — too many excellent books, from too many disparate sources. Working on a couple of novels, I closed myself off from the internet for several months and during that time I wrote in the mornings and afternoons, then did nothing but read in the evenings — long, uninterrupted reading that healed a fragmented brain and energized my writing. With that isolation, I found it possible to once again live in my own writing and the writing of others. It was one of the most peaceful periods of the last few years for me.

But this reading did indeed reaffirm the growing realization that between fiction in translation, mainstream realism, and fabulist fiction, along with a plethora of interesting nonfiction…who can really comprehensively cover a year of books? (Which is, frankly, such a boring and arbitrary way to measure time anyway — and, also, why do we continue to torment ourselves with mornings?) In the attempt to be too comprehensive, and of course failing, you might you do yourself an injury or in some way force the issue and wind up not having as much fun reading as you might have otherwise.

What you have before you, then, is a list of wonderful books I read in 2015, most of which were published this year. Some, however, appeared in 2014 and a couple date back two or three years. This feels like more of a natural rhythm to reading, or at least that’s the story I’m going with. I missed out on reading a few of the heavy hitters from 2015, but I also managed to discover some gems from 2014 I’d missed before. Along the road, too, I picked up some real stinkers from heavy hitters in 2015 that will remain unnamed. (You know exactly who I mean — that book you hated with the intensity of a million exploding suns. Yes, that’s the one. I hated it, too. Good, I’m glad we’re all in agreement here.) I note no particular trends because I think trends are often just some kind of obstruction in the eye of the beholder — for example, I picked up a lot of great fiction in translation and I also published a massive tome of fiction in translation. Ergo, this was the year of fiction in translation. But…was it? Outside of my house?

Finally, I decided this year to single out three titles for special praise, my top picks for novel, short story collection, and nonfiction from 2015. I would also like to congratulate New Directions on what I thought was an extraordinary year for them, with five titles on my list. They also published some truly beautiful books from a design standpoint.

Best Novel of the Year

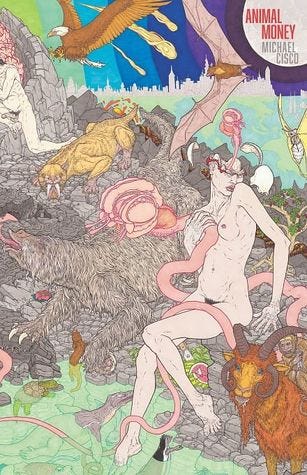

Animal Money by Michael Cisco (Lazy Fascist Press)

After I read the first quarter of Michael Cisco’s Animal Money, I was so overcome I ran around the outside of the house three times in the dark in my bathrobe shouting “Michael Cisco is a fucking genius!” Parasite tongues whispering public policy to the politician whose mouth they inhabit. Economists engaging in jumping competitions to decide primacy among competing theories. Spells to raise the dead conducted on airport tarmacs. Six intermingled rogue points of views and a continuing (possibly fabricated) life-story for an experimental physicist who incorporates the uncanny into her science and forever transforms the Earth. What madness is this: that it all works so seamlessly? In such sublime absurdist fashion.

But perhaps I should back up. Animal Money is “about” five economics professor who come up with the (surreal, radical) idea of animal money after meeting one another at the hotel of a conference they aren’t able to attend because they’ve all suffered coincidental injuries that require each to be heavily bandaged in some way. This bonds them as a group and a series of adventures ensue that include a weird zoo and a nudist beach. It’s written at a break-neck pace and in a style that’s very accessible. Cisco more or less piles brilliant set piece on top of brilliant set piece — and then in the most brilliant move the narrator begins to share space with narration by the other economic policy wonk academics and additional voices, at a point in the narrative where the reader has come to see them as one being anyway. All while Cisco also mercilessly skewers the world banking system and the peculiarly abstract world of money in general. He also manages to out-Clark Ashton Smith for Smith-like weird imagery, and certain sections are flat-out visionary and hallucinogenic in the best possible way.

I think of this novel as not just possibly the finest weird novel of the modern era, but also an uncanny Infinite Jest by way of early Pynchon and Robert Bolaño’s 2666. This novel requires your full and undivided attention, but will not come away from the experience unchanged.

Runners-up: Eka Kurniawan’s Beauty is a Wound (New Directions, translated by Annie Tucker) and Uwe Tellkamp’s The Tower (Allen Lane, translated by Mike Mitchell)

Best Story Collection of the Year

The Complete Stories by Clarice Lispector, translated by Katrina Dodson (New Directions)

As I wrote for Slate earlier this year, “Finding the absurdity or oddness in reality is, in isolation, a good enough magician’s trick, one that has sustained entire literary careers. But the joy in discovering Lispector is that she fuses the trick to a simultaneous sense of the universal, often in the same sentence or paragraph. Her characters could never be anyone else, yet they are also all of us. Reading these stories, I had the same feeling I had when I first read the collected stories of Angela Carter and of Vladimir Nabokov: that something lives beyond the skin and in the skin, and you welcome the invasion, you begin to long for it every time you’re away from the book. You read slow, you read fast, you hold stories back and then devour them, you dread that moment when you’ve finished the last of them. Because the strangeness is familiar and yet different than you’ve ever encountered before. Because life seems more vital, almost hyperreal, after reading Lispector, and it is harder to ignore the hidden life surging all around you, in all its many forms.” Since then the collection has only grown more significant in my thoughts, in part for how Lispector fuses so uniquely the real and the surreal. The epic “Brasilia” has rewarded several re-readings, as have other stories in this soon-to-become iconic collection. Simply brilliant.

Runners-up: Joy Williams’ The Visiting Privilege (Knopf) and Amelia Gray’s Gutshot (FSG Originals)

Best Nonfiction Book of the Year

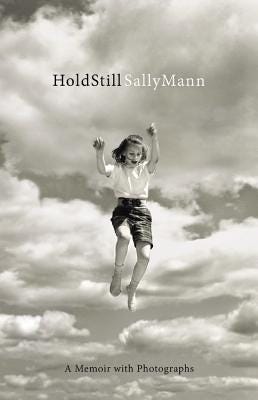

Hold Still: A Memoir with Photographs by Sally Mann (Little, Brown)

Has anyone found an attic more intellectually and historically valuable than that of photographer Sally Mann? In Hold Still, her attic divulges crimes, family foibles, blow jobs, car crashes, murder, and much more. (My own attic has a squirrel in it. End scene.) By working in the source of her source material, Mann is slyly pointing to the source of inspiration in a book that is, in part, about inspiration. However, even given the chapters focused on the controversy created by publishing candid photographs of her children, this memoir would be much the poorer if it didn’t also deal with race relations and various true and false visions of the South. No creator exists in a vacuum, and Mann’s honesty across not just the subject of her family’s eccentricities but the milieu in which she grew up also serves the valuable purpose of preserving something unique. The photographs are interesting but it’s a testament to Mann’s talent as a writer that they often seem superfluous. Whether it’s making us understand a bygone era or the process behind her art, Mann has a discerning eye. I felt after reading that I knew Mann in the way a friend might, but also that I had gained essential insight into the creative process itself.

Runners-up: The Soul of an Octopus by Sy Montgomery (Atria Books) and Learning to Die in the Anthropocene by Roy Scranton (City Lights)

***

Other Selections

Fiction/Poetry

The Musical Brain by Cesar Aira, translated by Chris Andres (New Directions)

It’s no surprise that Aira’s collected stories share some of the same attributes as his wonderful novels — those novels are sometimes only medium-length novellas. What struck me most about these fictions is that Aira likes to teeter on the edge between realism and fabulism. There’s a sense of the contes cruel suffused with Kafka and weird ritual a la Thomas Ligotti, but with more of a fantastical air than a horrific one. The title story “The Musical Brain,” with its sense of decadent spectacle, shares some affinity with tales by Gustav Meyrink and other writers who engage in grotesqueries, while others like “The Ovenbird” are both grotesque and metafictional, real and definitely not-real. There is an ovenbird…and yet there isn’t. Above all else, Aira makes an art form out of a purposeful meandering. The stories rarely provide standard plots or resolutions, but wind up in interesting places and often seem like perfectly formed jewels.

Kern by Derek Beaulieu (Les Figues Press)

If letters have lives, as Johanna Drucker suggests, then Beaulieu has herein documented some of the more interesting and opulent of those lives. Not only that, he has catalogued entire ecosystems and diverse species of letters. Kern is part of the Global Poetics Series but also functions as a kind of experiment in meaning and as an art book. The distinction between the figurative and the literal dissolves as you turn the pages, encountering ever more complex experiments in typography. You can enjoy the book as conceptual poetry or as art or as brilliant letterpress creations. The best poem-images in Kern have a lovely sense of motion, as if depicting dancers, while others resemble maps made of letters. A few slink along like previously unknown lifeforms. Throughout, there are beautiful progressions, crescendos of climax, and then the quiet slow burns of endings.

Dark Matter by Aase Berg, translated by Johannes Göransson (Black Ocean)

Like some kind of procrustean monster-deity communicating to us in human language for the first time, Aase Berg in her poetry conveys an alien profundity and, in poems like “In Reactor,” an almost geologic expanse to her vision of time and space. In prose-poems like “The Animal Gap” and “Ampules from the Lust Garden of Suffering,” she more or less attempts to find a new way to think about the world and our place in it — wrenching language out of its preordained tracks. It’s no surprise to discover Berg became involved with poetry through the surrealists, and in a darkly glittering way her work attempts to find that moment of “convulsive beauty in the service of liberty.” I find her work deeply emotional, even when it leaves the human, as we know the human, far behind. I am also reminded of equivalents in tone in other media, like Scott Walker’s album “Tilt.” Along with the work of Joy Williams, Clarice Lispector, Eka Kurniawan, and Amelia Gray, discovering Aase Berg this year has been a revelation, one that has forever changed me. “Bebirded, abandoning/pull your deep claw out of me.”

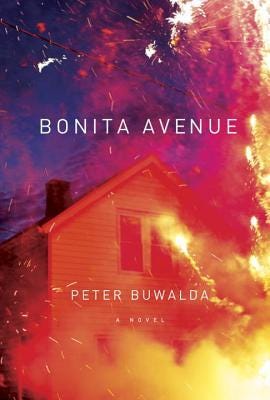

Bonita Avenue by Peter Buwalda, translated by Jonathan Reeder (Hogarth)

When I finished Bonita Avenue, this Dutch author’s English-language debut, I knew it was definitely a very good and structurally interesting book. But over the next nine months the novel has only grown more powerful in my imagination, and certain scenes have gotten stuck in my head and I can’t get them out. For example, I will never be able to view either broken glass or smoke rising through snow in the same way again. Buwalda skillfully charts the course of a dysfunctional family with many secrets and, in the formidable Professor Siem Sigerius, a stubborn patriarch whose past may destroy his family. The characters are complex, often amoral, and masterfully observed by the author. The drama and pathos are offset in a lovely way by dark humor and absurdity. Buwalda handles the revelations of mysteries in both the present and past with remarkable assurance. The novel’s climax is chilling, unforeseen, and in some ways, profound.

Broken Monsters by Lauren Beukes (Hachette)

Out in trade paperback this year, Broken Monsters is a tour de force of disparate voices, in the way that Beukes conjures up such a wide range of characters and makes them real, immediate, and believable. Set in Detroit, the novel trades off of a deceptively familiar serial killer set-up to reach deeper and wider territory. Not only is the antagonist unique and well-rendered, but the crimes have an odd, spooky (if terrible) integrity that compares favorably to the best moments on the television show Hannibal. But Beukes isn’t interested in spectacle, although she does spectacle well. The novel also comments in interesting ways on the nature of art and the nature of our fragmented reality. And while the speculative and horrific elements are masterful, it’s the conjuring up of, for example, the complex voices of teenagers that makes Broken Monsters truly unique.

The Xenotext: Book 1 by Christian Bök (Coach House Books)

Poetry, conceptual or otherwise, needs to be in some way engaging to the reader; which is to say, whether a poem is intellectually engaging in an abstract way or immerses the reader in something concrete and sensual, the work can, to me at least, only hold value if it is more than the concept it embodies. The Xenotext came out of an outrageous experiment, but is intriguing on the page as well as in the realm of ideas. Bök has encoded a poem called “Orpheus” into the genome of a germ, so that the cell in question builds a protein that encodes yet another poem, “Eurydice.” Having demonstrated this idea in E. coli, Bok plans to insert his poem into a deathless bacterium, thereby writing a text able to outlive any apocalypse. Well, okay, maybe sometimes an idea is worth a thousand words. But the words are very entertaining, too. In sections entitled “The Late Heavy Bombardment,” “Colony Collapse Disorder,” and “The March of the Nucleotides,” Bök explores science-fiction concepts through experimental poetry. “Writhing in the innards of these cattle there swells a gale of bees, uprising through the rent ribs” reads one line, exemplifying how Bök gives concrete form to the abstract.

On the Edge by Rafael Chirbes, translated by Margaret Jull Costa (New Directions)

Mordent, ruminating, a slow burn, On the Edge depicts a Spanish town whose inhabitants are reeling from the collapse of the economy — in which context the discovery of a dead body in the marshes is just one more misery. The bankrupt owner of a factory, Esteban, is in part the center of the novel, but Chirbes employs several voices, and verges on the omnipotent voice in certain sections. Each new layer brings additional depth and context, along with odd pathologies, revealing a portrait of a place that hasn’t yet dealt with the past, dead bodies aside. Chirbes likes long paragraphs and a pacing that requires patience, but once you become acclimated to it, the book seems more urgent and at a certain point transforms into something approaching a page-turner.

Purity by Jonathan Franzen (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

As ever, Jonathan Franzen charts the eccentricities and absurdities and contradictions of his often conflicted and unlikeable (but always interesting) characters. Last time, Franzen framed the personal against the backdrop of ecological issues; this time the context constitutes a blistering critique of the post-information age filtered through Franzen’s enduring thesis — that everyone is fucked-up and no one is or can be ideologically pure, because humans aren’t built that way. The main character, Pip, navigates dangerous waters that include revelations about her past and decisions about her future. Along the way she meets the Devil, in the form of Andreas Wolff, a kind of off-brand Julian Assange, but with some of Assange’s same contradictions between public persona and private life. Trademark absurdist humor is atypically for Franzen a little muffled, but the novel is also less sprawling than predecessors. Freedom remains Franzen’s masterpiece, but many of its virtues carry over into Purity, including an ability to make us understand and feel empathy toward sometimes prickly and anti-social characters.

The Librarian by Mikhail Elizarov (Pushkin Press)

As I wrote over at Slate for their list of the most underrated books of the year, “In this brilliant winner of the Russian Booker Prize, the novels of a boring, pedantic Soviet-era writer turn out to convey unusual powers for those stalwart enough to read them through to the end. Rival groups of ‘librarians’ hoard the books and thus the powers, resulting in several bloody conflicts. From there, Elizarov meticulously spins out a tale by turns hilarious and harrowing. A metafictional conceit becomes very intense and tactile due to the Ukrainian author’s own unusual powers — without undermining the absurdist elements. Immensely entertaining, The Librarian lives up to comparisons to the work of Gogol and Bulgakov while being very much its own thing.” I’d add only that this is a very accessible book, a page-turner that should appeal equally to the realist and the fabulist.

Not Dark Yet by Berit Ellingsen (Two Dollar Radio)

As we spiral further and further into an era defined by climate change, the fiction we require to explore these issues and the forms it will take are evolving. Much of what we think of as near-future or mid-apocalypse fiction will soon feel dated or even morally reprehensible, nothing more than nostalgia dressed up as disaster porn. But in Not Dark Yet, Ellingsen charts a new course that is at times Kafkaesque and always mesmerizing. Never didactic or predictable, the novel follows a main character whose time in the military and subsequent interactions involving an experiment with owls have come to define his life. As we follow this character through events both surreal and painfully personal, Ellingsen also ties in elements related to our fascination with space travel and locally sourced products. The result is, indeed, “not dark yet,” but getting there. An ambiguous and luminous and mysterious text that changes shape and meaning on rereading, as with all the the best fiction.

The Loney by Andrew Michael Hurley (John Murray)

This stunning novel about faith and the uncanny is in some ways a literary successor to the work of Robert Aickman, although little mutterings and stirrings of Arthur Machen, Algernon Blackwood, and certain of M. John Harrison’s stories peer bright and bat-like through the spaces between the words. The narrator recounts in quiet yet suspenseful detail one particular Easter trip to a remote area of wilderness known as The Loney. The family is accompanied by the new parish priest, who fits in uncomfortably with the community at large. Hurley’s ability to know when to insinuate and when to full-on show lends great depth to the characterization, and our understanding of the various members of the family changes over the course of the narrative. The old cottage the family stays in and the strange men living nearby are equal source of terror, without seeming to be there just to create tension. The shadow of the old priest across the story, the history of the region, and what happens to the narrator on one long-ago trip converge to create an instant classic.

Gutshot by Amelia Gray (FSG Originals)

It has been rather difficult to trust the sanctity of the walls of my own house since reading Gray’s story “House Heart,” and the collection as a whole had me doubting the sanctity of the walls of my mind, too. I bought the collection in a bookstore where the clerk told me point-blank “That book is way too weird for anyone.” I replied, “Really? I think the author’s fiction is quite normal,” and gave the clerk a look as if they were the weird one — my usual approach in such situations. Still, it’s true that Gray does have a knack for drilling right into your brain with images and situations that resonate in unusual ways. The stories also exhibit a dark sense of humor and brilliant compression, making many other story writers seem long-winded. The sentences are just wonderful, even when describing the horrible (especially then), even when I just, as now, randomly pick out the first one I flip to: “The sun beats the shit out of a dirty road called Raton Pass where the closest thing to a pair of matching earrings is a guy named Carl who punches you in the head with his fist.” I think of Gray as a take-no-prisoners kind of writer — uncompromising, fascinating, and “edgy” in a way that reclaims the validity of that word. I both adore and am a little terrified by Gutshot and think of the stories often.

The Winter Family by Clifford Jackman (Doubleday)

Bloody, amoral, and uncompromisingly bleak in its vision of the adventures of outlaws in the old West during and right after the Civil War, Jackman’s debut manages somehow to invite comparisons to Blood Meridian without seeming like pastiche. Highlights include a chilling character who only laughs and the vagaries of the Winter Family itself, which has its own code of conduct, and comes up against enemies as compromised as they are, or even more so. The novel unspools in brilliant set pieces that take place in Georgia and points more northern, like Chicago, with intervening sections of summary that read like chaotic, bizarre American folktales. The cleverness of using this summary to simply bypass any possible lulls is matched by attention to detail — both in recounting depravity and in keeping the reader right there, in the moment, during gun fights. Not exactly for the Jane Austen set.

Year’s Best Weird Fiction: Volume 2, edited by Kathe Koja and Michael Kelly (Undertow Publications)

One issue for non-realist fiction over the years has been the lack of year’s best anthologies with rotating editors, which tends to help democratize the process of establishing canon. Another issue, specific to “weird fiction,” is a proliferation of horror, science fiction, and fantasy year’s best anthologies that all have blind spots when it comes to certain kinds of unclassifiable fiction. The Year’s Best Weird Fiction has provided a corrective for both problems — and has especially hit its stride with volume two, under the editorship of iconic weird-fiction writer Kathe Koja. Her selections include a quietly powerful story by Julio Cortazar as well as sublime work from Nathan Ballingrud, Karen Joy Fowler, Caitlin R. Kiernan, Carmen Maria Machado, Karin Tidbeck, and the brilliant new writer Usman T. Malik. No finer year’s best was published in 2015.

Beauty is a Wound by Eka Kurniawan, translated by Annie Tucker (New Directions)

This Indonesian author’s English-language debut is scatological, scandalous, lively — beautiful and dark and messed up and fantastical. Terrible things happen and gorgeous things, and Kurniawan handles all of it with grace and empathy. Beauty is a Wound is like One Hundred Years of Solitude kicked into another gear, with an almost punk sensibility housed within gorgeous writing — and stories coiled within stories within stories. One of the most brilliant things about the novel is how Kurniawan never loses the thread even when spinning so many tales at once. This is especially impressive because his account is so matter-of-fact harrowing yet also darkly humorous. Somehow, too, he can write fairly traditional realistic scenes that exist side-by-side with almost surrealistic visions, without the result seeming tonally inconsistent. As a reader I was blown away. As a writer, I was taking notes to try to figure out how Kurniawan managed to create such a fusion. For those who prefer stolid realism and novels that don’t run around the yard getting into mischief, a second by Kurniawan released this year, Man Tiger (Verso), is still fantastical (and very good) but staid by comparison.

The Flame Throwers by Rachel Kushner (Scribner)

I know I’m coming very late to Rachel Kushner’s fiction, but I encountered The Flamethrowers for the first time this summer and could see no way to leave it off of this list. From the very first scenes of the protagonist driving her motorcycle down to Nevada to participate in a race, to the depictions of the 1970s New York art scene, I couldn’t stop reading this sharp, incendiary novel. I actually am not a huge fan of motorcycles, but the utter genius of the novel is that even if your mother had been run over by a motorcycle and a motorcycle had laid waste to your house and taken over your job and driven your children away from you, all the while insulting you on social media…you’d still be mesmerized by the sections of the novel in which Kushner describes the experience of riding a motorcycle. Kushner also skillfully weaves in details about the past to create a rich, kaleidoscopic vision of her characters’ lives.

Get in Trouble by Kelly Link (Random House)

The “national treasure” Kelly Link (as Neil Gaiman put it) gets in trouble in her latest collection, mostly by continuing to write idiosyncratic and surprising short fiction. Whether it’s the autumnal and pitch-perfect “The Summer People” or the raucous and deliberately fragmented “I Can See Right Through You,” involving ghosts and a demon lover, Link cuts right to the heart of her characters’ lives. Her use of fantastical elements is subtle, smart, and at this point in her career organic and seamless. Link’s fiction also seems deeply weird, even when it contains pop culture referents — something odd moves beneath the surface, something ancient and dangerous. I particularly liked “Valley of the Girls” and “Origin Story,” but the thoroughly engrossing thing about Link’s work is that it changes. The next time I read these stories, something else will rise up from the pages.

Satin Island by Tom McCarthy (Jonathan Cape)

Even merely adequate granularity in fiction that tackles the post-Information age is hard to come by — most writers get it wrong or have just enough understanding of the complex and shifting paradigm to define it properly in their fiction, but not enough to be fluid in deploying what they know — to make that information move and perform complex maneuvers. Usually it’s depressingly a bit like watching a human swimmer in a race with a dolphin. But, as it turns out, Tom McCarthy is a dolphin when it comes to this subject, and Satin Island contains the evidence. His opening airport sequence would be brilliant first of all for how its privileging of a transitional space symbolizes so much more about the modern world and the main character, but McCarthy’s layering-in of television coverage of an oil spill lifts these scenes into what I would call genius-level territory. The way in which oil is fetishized and seeps into the beginning of the narrative in a metaphorical way recalls other brilliant works like Reza Negarestani’s Cyclonopedia. But that’s just the start of a pseudo-corporate adventure and tour of the fractured-fragmented world of fiction-becoming-nonfiction that we live within today. An investigation into skydiver deaths sends up the Cult of the Great Conspiracy, while the narrator’s attempt to create a singular Report for his boss provides a great deal of room for satire within a context that is all-too-real. The ending contains a level of mundane reality that may be as startling as climbing out into the sunlight after being underground for a year (get the hell out of your virtual reality) and also contains a revelatory (and absurdist) take on one of the main relationships in the novel.

Thus Were Their Faces by Silvina Ocampo, translated by Daniel Balderston (New York Review of Books Classics)

Because too few readers know the extent of Silvina Ocampo’s contribution to the literary arts, here’s a primer: She was an influential Argentine writer, translator, and playwright who published more than twenty books of poetry, fiction, and children’s stories. Along with her friend Jorge Luis Borges and her husband Adolfo Bioy Casares, Ocampo, came to epitomize Latin American fantastical literature prior to era of Julio Cortazar and Gabriel Garcia Marquez. Her sister Victoria Ocampo founded and edited the iconic journal Sur, with several of Silvina Ocampo’s literary works appearing therein. It’s also sometimes forgotten that Silvina Ocampo co-edited the classic Antología de la Literatura Fantástica with Borges and Bioy, later published in English as The Book of Fantasy. Italo Calvino wrote of Ocampo, “I don’t know of another writer who better captures the magic inside everyday rituals, the forbidden or hidden face that our mirrors don’t show us.” This year’s Thus Were Their Faces, collected stories, with an introduction by Helen Oyeyemi and a preface by Borges, begins to redress a serious and bizarre lack — that of finding her fiction in English. The collected stories — dark, gothic, fantastic, impressionistic, and grotesque — include a mysterious and highly recommended novella, “The Imposter.” In her introduction to Thus Were Their Faces, Ocampo notes that she fought with her teacher de Chirico over the way he “sacrificed everything for color” and that she turned away from painting to writing so she could more clearly see “the forms amid the color.” There are many forms amid the colors in this great composite collection, and hopefully will lead to more of this writer’s work being available in English.

War, So Much War by Mercè Rodoreda, translated by Maruxa Relano & Martha Tennent (Open Letter)

Mercè Rodoreda has been a favorite of mine ever since college, when I encountered her story “The Salamander” in a world literature anthology I bought at a second-hand bookstore. As you might expect, the story wasn’t just about a salamander (although, yeah, it was about a salamander). Instead, it was transformative, utterly unique, and combined an astute eye for the natural world and a great sense for the fantastic with a feminist subtext. That “mix” sums up much of the great Catalan writer’s oeuvre. War, So Much War, the latest translation of her work following volumes of short stories and the darkly sublime novel Death in Spring, is a phantasmagorical journey through a landscape of war. People disappear into the sea. Cat men made out of broken parts try to make their way in the world. A kind of anti-picturesque episodic adventure, the novel makes sense of war through the nonreal, makes us understand that in the worst circumstances the surreal is the every-day as well as the place people escape to because there is nowhere else to hide. Rodoreda fled to France during the Spanish Civil War, and spent two decades in exile. At various times she was not allowed to write in her native language. In that context, it has been extraordinarily satisfying to see more and more of her fiction in English translation. Very little of it was available at the time I first read “The Salamander.” War, So Much War helps to expand our understanding of a world-class writer’s fiction, with, hopefully more to come.

The Blizzard by Vladimir Sorokin, translated by Jamey Gambrell (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

Anyone who enjoyed Mikhail Bulgakov’s A Country Doctor’s Notebook (nonfiction) or, indeed, Franz Kafka’s “The Country Doctor” (fiction), or certain fictions of Tolstoy, will enjoy Sorokin’s half-bizarro, half-traditional riff on the idea of man of medicine stuck in the boonies and the weirdness that may ensue. Rather than a stuffy translation full of faux Russianisms, we get instead approaches that veer from the sublime to slapstick. Garin’s attempt to get to the village of Dolgoye to stop a zombie epidemic is as ill-fated as the protagonist’s attempt to get off a bridge between two countries at the beginning of Vladimir Nabokov’s Bend Sinister. Two steps back, one step forward, until, mired in the non-journey with the good doctor, the reader finally realizes that perhaps the point is not the same point as the destination on a map. Toward the end, Sorokin reaches grand heights of rhetorical flourish in the service of uniquely strange situations. The “transparent pyramid” may emit a delicate whispering sound and evaporate, but the detritus of some of the more eloquent passages will linger in reader’s minds for quite some time. Just remember, the grommet, the grommet “from the giants’ cleaver, was big. Very big. Heavy. Weighty. It weighed may poods, hundreds of thousands of poods, and stretched, stretched, stretched” for many miles.

Cat Country by Lao She, translated by William A. Lyell (Penguin Modern Classics)

Hounded to death during China’s cultural revolution, Lao She had difficulties with censorship throughout his career. His best-known work was Cat Country, originally written in the 1930s and brought to English-language readers first in 1970 and then in 2013 in a revised Penguin Modern Classics edition (which I first encountered early this year). In the novel, a traveler from China crash-lands on Mars only to encounter a species of intelligent cats that rules over the planet. Befriended by a local cat person, the narrator encounters various aspect of the cat culture, which are clearly stand-ins for various aspects of Chinese society and governance. The guts of this novel are both cleverly inventive and observant of the culture Lao She grew up in. The author clearly could have become the leader of a robust and vibrant science-fiction tradition in China in some alternate-history version of that country. The translation is excellent, and the text is entertaining and lively while also having considerable satirical bite.

The Tower by Uwe Tellkamp, translated by Mike Mitchell (Allen Lane)

A critically acclaimed national bestseller in Germany, The Tower received some attention in England but practically none in the U.S. upon its English-language release on December 30, 2014 (perhaps only in Canada and the U.K.). This is a shame because The Tower is a unique, sweeping, and lyrical novel that chronicles the lives and misfortunes of an upper middle-class family of intellectuals in East Germany during the last years of communism. In my experience, at least, it is unusual to encounter a novel about this era, evoking the Stasi and bread lines, that reads in part like one of Mark Helprin’s more fantastical creations. Gritty realism occurs within a context of a tradition of high culture and dinner parties, no less urgent from that perspective. Christian Hoffman, a conscript in the National People’s Army, comes home to see his parents and soon thereafter his uncle Meno fall afoul of the authorities. From there the novel opens up in unexpected and interesting ways. Epic in scope, The Tower is a classic in every sense, and Tellkamp is unafraid to unleash the power of poetic passages. “Searching, the Great River seemed to tauten in the approaching night, its skin crinkled and cracked, as if it were trying to anticipate the wind…”

The Illogic of Kassel by Enrique Vila-Matas, translated by Anne McLean & Thomas Bunstead (New Directions)

Poor Enrique Vila-Matas…or, rather, poor some version of Vila Matas. At the beginning of this at times metafictional novel, a novelist Enrique is invited to participate in the German Documenta exhibition by becoming a piece of performance art. He will be asked to spend time writing in a Chinese restaurant in the city of Kassel, possibly while passersby gawk or possibly to absolute indifference. Once in Germany, however, the nature of the assignment seems to change — as does Enrique’s enthusiasm for the project. In part it is Enrique’s overblown sense of his own importance that fuels the engine of the novel. In part it is the author’s (the real author’s) sense for what needs to be punctured and what needs to be celebrated in terms of the creative impulse. What follows stacks weirdness on weirdness, emphasizing both the virtues and pitfalls of conceptual art. The real achievement here is that a novel based so utterly on the abstract can feel so concrete and of-the-moment. Also of note are Vila-Matas’ A Brief History of Portable Literature and Because She Never Asked, both released this year by New Directions.

The Visiting Privilege: New and Collected Stories by Joy Williams (Knopf)

This comprehensive new collection from Joy Williams came as a total revelation to me because I had never read her fiction before. I can’t describe the sensation of reading Williams for the first time as anything other than being physically knocked off my feet. Even an early story like “The Yard Boy” contains multiple surprises, not least of which is a dead-pan hilarious deranged plant. “Winter Chemistry” is a beautifully nasty piece of work, never going where you think it will go, and ending so perfectly that in retrospect the path seems so natural. “Rot” feels fresh and new because Williams avoids the trap of many story writers who, because they would never do such a thing, are unwilling to “go there,” perhaps especially when “there” is a car in a living room. “Farm,” in which a drunk driving incident leads to, is a stone-cold classic of motivation and understatement, devastating and chilling. Structurally, the stories are fascinating to learn from, and even though some reviewers typify Williams’ work as “dark,” I don’t find it particular depressing because the specific detail is so perfect. An added bonus or overlay: Williams’ view of animals in these stories is an excellent example of a writer understanding that even if an animal in a story is not the focus of the story, that creature is still a part of that story, not just an inanimate bit of setting. Heady stuff, and highly recommended.

Vertigo by Joanna Walsh (Dorothy Project)

Slim books sometimes contain mighty and all-encompassing ideas, and such is the case with Walsh’s short story collection, from one of my favorite publishers. Echoing and evoking such writers as Angela Carter, Lydia Davis, and Clarice Lispector, but in her own unique voice, Walsh examines gender politics and the inequities of relationships in a hypnotic and personal way but within a space that is also universal. Stories such as “Claustrophia” are not so much polemics as state-of-the-nation non/fictions, and the intensity arises from precision of thought and image, the “lace tops with modesty inserts, and the spangles as if for nights out, the cardigans grown over with a fungus of secondary sexual characteristics –bristling with embroidery and drooping with labial frills.” Other tales like “The Children’s Ward” continually surprise and subvert throughout their short length: “Nevertheless I think I couldn’t kill the anesthesiologist…Nor do I think I could kill the surgeon, who looked like a banker without his suit. When [the patient] went under, did I want to kiss him?” I can’t stop quoting Walsh because her sentences are so excellent, and because all of her stories are constructed solely from excellent sentences. “I have had some good times in this body like right now.”

Nonfiction

British Columbia: A Natural History by Richard and Sydney Cannings (Greystone Books)

Sometimes you encounter a “regional” book of much wider interest. British Columbia: A Natural History (in a new, expanded edition) is a wonderful example. First off, it’s about an area of great biodiversity, an area that in contrast to many still has pristine and semi-pristine wilderness. In conveying a deep sense of the many intricate ecological zones that comprise British Columbia, the book succeeds brilliantly — not only is the information presented in an entertaining, clear, and interesting way without trying to simplify what needs to be emphasized as being complex and interdependent. The accompanying charts and graphs and photographs, unlike in many such books, really do illuminate the text and add to it. Even better, in order to discuss British Columbia in a meaningful way, the authors have to provide a primer on geology, biology, and ecology integrated into their discussion of this specific area. I appreciated this primer because the authors are such good writers that even basic concepts I already knew were interesting to read about again. What comes through, too, in a meaningful and passionate way is the author’s love of and connection to the area. The book is a practical and enduring expression of that love.

Drawn and Quarterly: Twenty-Five Years of Contemporary Cartooning, Comics, and Graphic Novels, edited by Tom Devlin with Chris Oliveiros, Peggy Burns, Tracy Hurren and Julia Pohl-Miranda (Drawn and Quarterly)

If there was a “no-brainer” selection for this list, it would have to be this compilation of text, art, and comics from Drawn and Quarterly. The little outfit that became a huge influencer and provided safe-haven for all sorts of comics artists who didn’t have other outlets has now given readers a lovely, lively, and sometimes eccentric account of its origins. With (sometimes new) work in D-Q 25 from Kate Beaton, Chester Brown, Yoshihiro Tatsumi, Art Spiegelman, Lynda Barry, Adrian Tomine, and many more, you could just browse through the art. But then you’d miss the commentary on how Drawn and Quarterly came to be, and how it grew, which is fascinating. Appreciations from various artists and influencers in book culture are often insightful. Taken in total, the book also gives readers a good idea of the evolution of the comics culture and some of the roadblocks that the press had to overcome to get to their current exalted and iconic status. I also appreciated the great endpapers and even the carefully chosen back-cover image of two dogs ripping apart a graphic novel.

The Deep Zoo: Essays by Rikki Ducornet (Coffee House Press)

One of our best and most enduring surrealists and sensualists, Rikki Ducornet intuits connections supersaturated with color and finds the intersection of myth, nature, and the literary world. This slim collection contains worlds wide and deep in nonfiction form. It opens up in the imagination like an amazing cabinet of curiosities or exquisite coffee-table book composed entirely of words. What is the “deep zoo?” It’s worth quoting Ducornet at length to convey some of the delight in reading these essays. “For Bachelard they take the form of shells, a bird’s nest, an attic; for Borges a maze, mirrors, the tiger; for Calvino moonlight, the flame, and the crystal; for Cortazar ants on the march and the cry of the rooster…For Borges, there is an evident sympathy between the tiger’s stripes, the world’s maze, language, and the maze of the mind; for Calvino, between moonlight and the lucent transparency of clear thinking; for Bachelard, between attics and a love of solitude; for Cortazar, between the cock’s cry and the knowledge of mortality, of infinitude.”

The Utopia of Rules by David Graeber (Melville House)

As someone who frequently found himself subjected to the tyranny of bureaucracy before becoming a full-time writer, Graeber’s book at times conjured up visions of hell. After one finds a dead mouse and dead plant in one’s desk or is asked repeatedly by the unhinged if one would like to “see a strange room,” the mechanisms by which governments and civil servants live out their strange lives become less ethereal and academic than dystopic and mind-numbing. Still, I was willing to entertain the idea that a less horrifying view of bureaucracy might have value, and I’m glad I did. I especially appreciated sections like “Dead Zones of the Imagination: An Essay on Structural Stupidity” and the appendix “On Batman and the Problem of Constituent Power.” I had less patience with the section entitled “The Utopia of Rules, or Why We Really Love Bureaucracy After All” — although that section doesn’t necessarily contradict my own theory that the entire world runs on absurdity, inefficiency, waste, and dumb-itude. At times I wished Graeber would have engaged more fully with the darker and more dysfunctional aspects of “bureaucracy,” but I have to admit that it is probably his chipper tone throughout that I’m objecting to more than anything else — that and because I am still having a hard time contextualizing a lot of the bizarre, absurd, and brain-killing experiences I have had in that world. In short, my own eccentricities should be no obstacle to readers picking up this fascinating and comprehensive book — one that will be influencing my fiction for some time to come.

To Our Friends by The Invisible Committee (Semiotext(e) Intervention Series)

In this follow-up to The Coming Insurrection (2007), the Invisible Committee commits to print an altogether post-Baudrillardian vision that, even if it’s a secondary purpose, reveals the difficulty of pushing out of or beyond the hegemony created by how the internet tends to commodify or take over for its own purposes causes and impulses. A list of points in the first chapters focuses in part on ecological issues and takes issue with the idea of the Anthropocene, although not from exactly the same position as some Marxists. To the Invisible Committee, it seems (and I could be wrong) that by labeling and measuring, humankind is engaging in the same kind of control that led us to the current climate change crisis. Other sections, on cybernetics, read like science fictional extrapolation. A critique of lives lived online as substitute for real rebellion has real power (especially in the context of climate change), and throughout the book the thoughts expressed have a provocative, wake-up-and-untie-yourself-from-the-railroad-tracks value. At times, a note of exasperation dominates, as if the Invisible Committee believes its disciples have misunderstood the message, but the analysis provided herein is a useful launch-point for pushing back against underlying assumptions about our world.

Forms: Whole, Rhythm, Hierarchy, Network by Caroline Levine (Princeton University Press)

There’s something to be said for certain academic books — and the thing to be said is that even if you don’t have the background and context to extract the meaning of every morsel, they can still be incredibly stimulating. I’m still not sure I have the understanding of literary theory to grok all of Forms, but I’m damn sure I found the book entertaining and informative — one of those books that change the way you think about fiction and even your own work. First and foremost, Forms is meant to wrench our thinking out of its predictable modes, even when it is doing so second-hand, by referencing other texts. In finding new pathways to linking the literary to political, social, and historical context, Caroline Levine in effect creates new realities in the reader’s mind. I found particularly fascinating sections like “Affordances,” wherein the author examines the underpinnings of textures like glass, steel, and cotton — and how assumptions about those elements in terms of design can undermine or lift up creative works. I must say, I love a sentence like “The idea of affordances is valuable for understanding the aesthetic object as imposing its order among a vast array of designed things, from prison cells to doorknobs.” There is no way to provide a full synopsis of this book in this short space, but perhaps this will help: Forms interrogates the tactile reality of our world, and how we convey that in the “virtual reality” of fiction. In doing so, it performs the valuable service of reminding us that everything has social and political ramifications — in part because everything we create first existed in the subjective reality of someone’s imagination.

Brilliant Green: The Surprising History and Science of Plant Intelligence by Stefano Mancuso and Allessandra Viola, translated by Joan Benham (Island Press)

This slim volume with an introduction from Michael Pollan would probably drive one of my botanist friends around the bend, due to its assertions about plant sentience. However, it is a fascinating exploration, across a couple dozen essays — one that seeks to expand our understanding of plants and to help us better see the interconnectivity of our biosphere. In recent years we have realized that photosynthesis is a much more complex process than previous thought, and chronicled the ways in which plants use fungal thoroughfares to community. In Brilliant Green, the authors identify the dozen or more senses plants have, discuss how plants have been viewed by various religions, argue that in terms of evolution plants are superior to human beings, and, above all else, make it clear that we don’t yet understand all of the nuances and complexes of flora around the world. A mind-expanding book in all ways.

The Soul of an Octopus by Sy Montgomery (Atria Books)

How, exactly, are we primitive humans supposed to judge the intelligence of more fluid creatures like octopuses, whose neurons aren’t collected like feudal lords inside one castle-keep, but distributed also in their tentacles? That’s at least close to one question raised by Sy Montgomery in this engaging and user-friendly book on octopus behavior sentience. The Soul of an Octopus provides a wealth of general information about octopus behavior; for example, that they “use their funnels not only for propulsion but also to repel things they don’t like, just as you might use a snowblower to clear a sidewalk.” Montgomery has a knack for making her observations relatable — and for giving the reader both specific data and anecdotal evidence to support her claims. By framing the information with her own stories about octopuses she’s also acknowledging that cephalopods need the humanizing touch because the idea of “octopuses with thoughts, feelings, and personalities disturbs some scientists and philosophers.” In an era when we’ve come to recognize that otters understand the concept of death and even fish appear to be more highly socialized than previously thought, it’s a little sad we need more books like this one. But we do.

The Spectralities Reader: Ghosts and Haunting in Contemporary Cultural Theory edited by Maria Del Pilar Blanco and Esther Peeren (Bloomsbury)

Do you believe in ghosts? Well, they believe in you. From the uncanny in the work of Nigerian legend Amos Tutuola to the ethereal projections in Henry James’ novels and stories, The Spectralities Reader collects some fascinating nonfiction about our obsessions with wraiths, haunts, and other unseen impulses. Whether you want to explore capitalism and ghosts or Walter Benjamin and ghosts or being buried alive with ghosts, you’ll find something of interest in this massive anthology. A fair amount of the material is deeply analytical and rife with footnotes, but there’s still enough of interest here for the layperson. Some will simply delight in terms like “Hauntology,” “Spectropolitics,” “Textual Haunting,” Phantasmic Radio,” and, of course, “Ghostwriting.” Others will delve deeper into a world of invisible memes and subtextual stirrings. “When the lights go out, hearing stays awake.”

Learning to Die in the Anthropocene by Roy Scranton (City Lights Books)

As we find ourselves more and more entangled in the Anthropocene, in thrall to global warming, books that are low on bullshit and high in value are not only important but at a premium. Unlike many other attempts, Scranton’s Learning to Die in the Anthropocene deals with the issues head-on, understanding that avoidance doesn’t deter catastrophe. Instead, an understanding of the facts leads to being able to move beyond inaction to being usefully proactive. It’s not in any way coincidental or beside the point that Scranton quotes Spinoza at the beginning of his slim but wise tome: “A free man thinks of death least of all things, and his wisdom is a meditation of life, not of death.” In stripped down chapters like “Human Ecologies,” “Carbon Politics,” “The Compulsion of Strife,” and “A New Enlightenment,” Scranton makes passionate, accurate arguments that our current form of civilization is doomed. At the same time, from the ashes of this stance, he also offers hope if we can change our behavior. Above all else, we must accept the entirety of our predicament or we will never be able to find the perspective to move past it. Oddly, or perhaps not oddly, there is much about Scranton’s approach that is wise in how we deal with other aspects of our lives, and much that speaks to finding general contentment.

Waste by Brian Thill (Bloomsbury)

This slim volume is filled with garbage, but it’s meant to be filled with garbage. As the author notes “Though we try to imagine otherwise, waste is every object, plus time. Whatever else an object may be it is also waste — or was, or will be.” In such fascinating chapters as “The beach that speaks,” “Pigs in space,” and “Million-year panic,” Thill explores the history and future of waste. He speaks from good authority; when he was a kid, before he wanted to be an astronaut, he “wanted to drive a garbage truck.” From the movie Raiders of the Lost Ark to W.G. Sebald’s fiction, Thill painstakingly, and with precision, tackles his subject. The compression on display is impressive — rarely have so few pages contained so much interesting information. Although less of a how-to manual and more of an examination of evidence, Waste is a good companion volume to Roy Scranton’s Learning to Die in the Anthropocene. Both books are trying, in a level-headed way, to bring us to a specific and essential understanding of our modern situation.

Ancient Pathways, Ancestral Knowledge, Vols. 1 and 2, by Nancy J. Turner (McGill-Queen’s University Press)

This remarkable two-volume set focuses on the plants and environments of the British Columbia region. I found these books after a wet, water-logged walk through the University of British Columbia’s Botanical Gardens. It was a terrible, terrible day to go walking through the gardens, with the wind lashing our faces, and it was cold as hell, but we did anyway: an invigorating walk through a landscape made even more beautiful by the weather. Then we went into the gift shop on the way out, and I picked up Ancient Pathways and read the description and had to have it. Forty-five years of research and talking to indigenous botanists and other people in the First Nation communities led to the creation of a book that not only preserves knowledge but ties it all together across communities. Yes, there is a lot of detail about plants, but there is also enough general context and enough mysteries that the book doesn’t read like an encyclopedia — sometimes, as Nancy J. Turner follows the clues about a particular habitat or plant, the book almost reads like a true-life mystery. As a result, Ancient Pathways is never less than riveting. It is also a cultural history as well an environmental one, and that confluence speaks to the new (and old) ways in which we need to think about the biosphere today.

Black Flags: The Rise of ISIS by Joby Warrick (Doubleday)

Rising above sensationalism or unsubstantiated claims, Black Flags provides a cogent and useful analysis of the pre-ISIS landscape in Iraq and Jordan. In a context in which Western journalism often provides incomplete analysis, Joby Warrick gets inside the genesis of ISIS in Jordanian prisons and its subsequent spread due to a series of unique events. The Western division of the Middle East after World War I is in part to blame, and so too is George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq and subsequent disbanding of the Baathist Iraqi army. ISIS could not exist in such a potent strategic form without the combination of Baathist military experience and the ideological fervor of a deviant form of extreme Islam. Nor could it exist without the extreme cynicism of Syria’s Assad being willingness to hold onto power by allowing his country to slide into chaos. What Warrick does expertly is show how Jordan, on the front lines of possible terrorist activity, tried tirelessly to expose and de-claw a proto-ISIS organization, and how that effort was undermined by U.S. war fatigue and other factors. He also chronicles how a bunch of thugs led by the infamous Zarqawi “found religion” as a convenient way to inspire others, and how even other hard-liners thought Zarqawi’s approach too extreme and distanced themselves from his example.