Reading Lists

Jeff VanderMeer’s Favorite Fiction from 2014

My year in reading was a chaotic and joyous one. There was nothing scientific or complete or logical about it, and I was glad I didn’t have to care about any of that. I was on the road exactly five months, two weeks, and three days. I grabbed what I could when I could and discarded anything that didn’t keep my attention in an airport, on a plane, in a cab, in a hotel room, in a cave, on horseback, talking to owls, at the end of a bar, dancing with lemurs, through a looking glass, back home for a couple of days.

So, in that context, it’s surprising what stuck and what didn’t. I lugged Richard House’s thousand-page hardcover The Kills around with me all over — undaunted by the fact that it was not built for shoving into an airplane seat-back pocket. It was the tome I could not put down, and it captured me so utterly that I begged off meal invites and bar get-togethers to finish it. I resented gigs because if I was reading my own work I wasn’t reading The Kills.

The borders of my reading in 2014 were porous and for this reason you will find a few titles from before 2014, like Submergence and Pym. I am not the kind of reader to begrudge a book its inclusion based on some arbitrary human calendar. (This will frustrate some of you; I apologize in advance.) Still, even I have some limits. I have not included “ancient” books that I read and loved this year — like Margaret Atwood’s Oryx & Crake and Robert Walser’s The Tanners. I also have stopped myself from adding the astonishing Thrown by Kerry Howley, “creative nonfiction” about MMA fighters that should appeal to any fiction reader due to its unique approach.

Throughout the year, whether they have books on this particular list or not, the publishers who made me happiest were, in no particular order, Two Dollar Radio, Coffee House, Melville, Milkweed, Dorothy Project, New York Review of Books Classics, Sarabande, Dedalus, Drawn & Quarterly, Subterranean Press, Europa Editions (and Picador generally), Tin House, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, and New Directions.

Here, then, are my carefully curated favorite reads of the year. I have divided this list into the following rigid genre categories: fiction.

***

City of Stairs by Robert Jackson Bennett (Broadway Books)

Author of the highly recommended American Elsewhere, Bennett returns with a fantasy novel that will appeal to a wide range of general readers. This novel has everything. Set in a fantasy world with dead gods, City of Stairs can be read as a spy novel infused with political intrigue. But Bennett also tackles colonialism, religious fanaticism, economics, the environment, and gender issues. On top of that, this layered and complex novel throws in magic, credible action-adventure, long-held family secrets, and a fresh take on mythology. All related from the point of view of Shara Thivani, who has been tasked with solving a murder. A murder? Why yes, it’s also a crime drama.

The Corpse Exhibition and Other Stories of Iraq by Hassan Blasim, translated by Jonathan Wright (Penguin)

Redeployment by Phil Kay has been juxtaposed, in some reviews, with The Corpse Exhibition as if allied by being on opposite sides of the mirror, or allied by a shared subset of geography, boots on the ground or of the mind. But I’d like to break that link here and say they aren’t allies. One is something we’ve seen before, even if done well. The other, The Corpse Exhibition, isn’t something we’ve seen before. There’s a welcome unchecked and unruly strain of surreal horror running through this collection, one that serves as a delivery system for a matter-of-fact grotesquery and absurdity. These stories do not support a comfortable view of the human condition. They do not support the status quo. These sophisticated and layered narratives chronicle how reality can seem like a dark dream, and how you have to live within that reality or that dream. We may be living in times where mimetic realism in fiction isn’t up to the task of describing the intra-dimensionality of experience.

Idiopathy by Sam Byers (Faber & Faber)

What do you get when you combine self-absorbed people, a cattle epidemic, rehab, a bio-dome, pregnancy, and a barbed writing style? Idiopathy. Since this novel skewers everyone and everything in modern consumer society, it’s no surprise that the Amazon reviews are dire. The more formal reviews were hit or miss, too. It’s not nice to be told that everything you value is for shit. Not nice! Not nice! Oh well. I guess we’ll have to live with it. Anyway, Idiopathy is a deeply hilarious and absurd novel full of unlikeable characters and inventive set pieces. A misunderstood book that deserved better than it got on this side of the Atlantic.

The Investigation by Philippe Claudel (Quercus)

Why be Kafkaesque when you can just be Kafka, returned from the dead? Claudel prefers stealing to borrowing — and it works due to a cringe-worthy beautiful unease. An Investigator is sent to a far-distant town to find out why so many people at an anonymous company are committing suicide. But the Investigator doesn’t even get to the company until several chapters in, such are the vagaries and disturbances of modern life. From weird hotel owners to strange rituals, The Investigation contains more than a hint of Robert Aickman, especially his story “The Hospice.” The Investigator is stymied not just by the people he encounters but the systems that have created the ridiculous words that spill out of their mouths. Surreal, hilarious, and disturbing, this is the novel about the modern world that Kafka didn’t live to write.

can’t and won’t by Lydia Davis (Farrar, Straus and Giroux)

I think of this collection as a series of personal diary entries, probably not by the same person, that I get the privilege of reading through even though I’m not part of the family. Because of Davis’ reputation I’m happy to wrestle with a three-line short-short that seems banal; I don’t care what spark or stance reveals to me the resonance. So I read this collection in an odd state of dueling boredom and deep interest. I must admit I like the longer pieces best, but there’s a kind of hypnotic hold exhibited by the shorter stories that I can’t quite explain. Even when ennui took over it was a kind of active ennui and I couldn’t stop reading.

The Wilds by Julia Elliott (Tin House)

My favorite collection of the year by a writer whose first novel comes out in 2015. The stories in The Wilds adhere to a nominally realistic view of the world, but there’s also a strong sense of the absurd running through them. Sometimes it’s overt and sometimes it’s sly. The randomness and spontaneity of the world often manifest through the dialogue. It’s an incredibly rare gift to make speech sound both off-the-cuff and essential to the story rather than just random. “The Wilds,” “Feral,” and “The Whipping” are three personal favorites, with a Southern flare that doesn’t degenerate into stereotype. But Elliott’s also doing really interesting and unique things with stories like “Regeneration at Mukti,” which is science fiction. These stories don’t owe anything to any writer, but sometimes there are glints and glimmers of Shirley Jackson and Kelly Link.

We Are All Completely Beside Ourselves by Karen Joy Fowler (G.P. Putnam’s Sons)

I read this novel by Fowler on the plane, next to someone who I hadn’t spoken to all flight. So I imagine the person was surprised when I burst into tears just as we started our descent. I’d reached the end of the novel. I’m not a sentimental person, but somehow Fowler’s tale of an unusual family, a terrible scientific secret, and the inequities of animal research got past all of my defenses.

Cat Town by Sakutarō Hagiwara, translated by Hiroaki Sato (NYRB Press)

A Japanese writer considered one of the foremost poets of the Taishō and early Showa periods, Sakutarō was interested in exploring madness, hallucinations, and obsession in his works. To do so, he largely rejected naturalism and used colloquial language, impressionistic images, a sense of personal intimacy, and modern subject matter. The classic “The Town of Cats” (1935) or, as here “Cat Town,” is the poet’s only short story and explores themes of disorientation and the illusory nature of reality. It depicts a surreal urban journey that presages the work of Haruki Murakami. But this lovely collection includes potent evidence as well of the author’s gift for poetry. “Signs of crimes and sins appear in heaven, appear on piling snow, glitter out of treetops…shining beyond midwinter.”

Fourth of July Creek by Smith Henderson (Ecco)

This debut is just flat-out brilliant from beginning to end. Set in Montana around 1979, it chronicles the conflict between a dysfunctional social worker and a crackpot preacher who has become a dangerous survivalist. As I wrote in The Guardian, “Henderson is committed to showing us unhappy and unstable people existing at the edges of any safety net. But they’re also people struggling to find a kind of truth, and they’re portrayed with compassion and humanity, in a voice that crackles and lurches with the intensity of a Tom Waits song. Here, at the beginning of his career, Henderson has come within shouting distance of writing a great American novel.” This one deserved all the prizes.

With My Dog Eyes by Hilda Hilst, translated by Adam Morris (Melville House)

As more and more Latin American women writers are translated into English, we begin to have a better sense of the true range of the surreal, irreal, and fantastical. This expansion is as yet incomplete and there is much, much more to come — many writers from the past whose fiction has yet to appear beyond single story translations in literary journals. But Hilst helps, especially with its disdain for literary tradition and for middle class mores. It’s scatological, merrily sexual, and not interested in telling a conventional story. A slim but potent text, this one will sear your brain. Translator Morris’s introduction provides great context and suggests treasures yet to come.

The Kills by Richard House (Picador U.S.)

This long novel split into four self-contained, interlocking parts is probably my favorite read of 2014. The basic set-up involves embezzled money, predatory military contractors, and illegal U.S. waste burning sites in the Iraqi desert. From there, The Kills metastasizes and transforms, continually shedding its skin. You can also think of this novel as a mimic with a through-line of exploring every ramifications of the decisions explored in part one. There are definite traces of Le Carre and other espionage writers but also war reportage, horror fiction, theater of the absurd, and much more. Moreover, The Kills is a sustained examination of the lies and myths we tell about ourselves. Comparisons to Bolano’s 2666, Catch 22, and Thomas Pynchon all make sense to me, even if The Kills is a unique creation. For this reason — this sense of encountering something unique — I found every page captivating in some way, but the shape of the story didn’t become clear until the last pages. At which point everything locks in place with impressive power; brilliant and brutal. I would suggest that The Kills and The Corpse Exhibition share a certain resonance. I see both books as harbingers of a paradigm shift — that, for example, what has baffled some critics about the sometimes brutal The Kills is exactly what makes the novel more relevant to and reflective of our times than a dozen more lauded books. There’s no escapism here, and nothing juvenile or nostalgic.

Safari Honeymoon by Jesse Jacobs (Koyama Press)

I read this graphic novel or it read me. I’m not quite sure which. A demented exploration of unfamiliar wilderness, Jacobs’ absurdist horror story deftly comments on and sends up invasive species and Western explorers alike. Jacobs has a gifted eye for the plant or animal detail that resonates and seems true despite ignoring the fidelity of biological illustration. As the two lovers on their honeymoon encounter an increasingly phantasmagorical ecology, their guide demonstrates hidden depths of both devotion and perfidy. Meanwhile, swarms of weird centipedes and other creatures look on, wide-eyed and innocent. (Or are they?) The adventures are surreal, creepily informed by a good working knowledge of parasites, and come with an underlying message: Intruders either succumb to bad ends or become assimilated…and sometimes being assimilated ain’t so bad.

Pym by Mat Johnson (Spiegel & Grau)

The oldest title on this list (from 2011), Pym was absolutely one of my top five reading experiences this year. This exploration of race and fiction through a modern riff on Poe’s classic yet at times problematic The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket is laugh-out-loud funny but also deadly serious. It’s beautifully layered and deep. The novel manages, somehow, to seem at times like the best essay on Poe ever written, without this in any way diluting its authority as fiction. It also reads like the best expedition story to the Antarctic, too. Somehow Johnson has managed to successfully wed the conventions of literary criticism, historical fiction, adventure fiction, literary fiction, and weird fiction. I loved it.

The Woman Who Borrowed Memories: Selected Stories of Tove Jansson translated by Thomas Teal and Silvester Mazzarella (NYBR Classics)

One unfortunate thing about the popularity of Jansson’s wonderful Moomin comics and stories is that her so-called “adult” fiction has seemed for decades to play second-fiddle, at least in English translation. New York Review of Books has done a fine job of rectifying this situation. The latest salvo is the selected stories of Jansson, with a useful introduction by Lauren Groff. The curation helps quite a bit because Jansson’s short stories have always seemed like the most hit-or-miss category in her creative output. This omnibus gives readers the best possible experience. I must also use this anchor to put in a plug for Jansson novels, in case you have not yet encountered them. The Summer Book is an elegant and wise exploration of the relationship between a granddaughter and her grandmother on a Finnish Island. The True Deceiver is a sharp knife between the shoulder blades, a clinical and unsentimental look at art and real-life relationships.

Nobody Is Ever Missing by Catherine Lacey (FSG Originals)

This uncompromising novel, in which a woman recounts leaving her husband and traveling through New Zealand is a brave, often darkly funny story about trying to find or lose your self while coping with loss and dysfunctional societal norms. It’s also a damn fine road novel. More than anything else, though, I admire how Nobody Is Ever Missing commits to the eccentricities of its narrator through its use of language. The spiraling, long sentences that I love so much. The returning to certain ideas or phrases, as a way of testing the walls of a prison. It threatens a repetition that could be tiresome but escapes the trap. The ending is just as fraught and messy as the beginning and middle. Nothing will ever be the same. Thankfully so.

Submergence by J.M. Ledgard (Coffee House Press, 2013)

A staggering accomplishment, with twinned narratives that join in the middle and are genuinely moving, ecstatic, terrifying, and profound. This story of a hostage and a woman who studies the deep ocean contains more interesting ideas about science and philosophy than any science-fiction novel I’ve read in the past decade. I was astounded by the layered compression, how the narrative manages to achieve so much in such a short span. I’ve never encountered anything quite like Submergence and I am rendered largely speechless and wordless by it. Thus, I guide you to Matthew Cheney’s marvelous review, for a more articulate reaction.

The Absolution of Roberto Acestes Laing by Nicholas Rombes (Two Dollar Radio)

I very much enjoyed this weird, disturbing, sometimes effed-up novel about strange films, lost films, and the fragile faith in the difference between our fictions and our realities. A journalist and film buff interviews an eccentric filmmaker/professor. It is profitable for the reader’s entry point into the novel to think of it as consisting of a series of loosely interlocking short stories, in the form of film descriptions. The section involving a quest by an engineer to repair an abandoned well is particularly stunning. An image of dark drones so thick across the sky it becomes night is incredible. One passage in particular had a truth to it that I cannot forget: “The end of the world is really a reactionary fantasy, the dream of thin-blooded tyrants, spun into popular narrative by writers and artists and movie makers. The landscape around her — the broken roads and disfigured buildings and polluted rivers — is not some dystopian fantasy of the slate-wiped-clean but something far more dangerous: things as they are. The present is always the present, even when it seems like the future.”

Lesabendio: An Asteroid Novel by Paul Scheerbart, translated by Christina Svendsen (Wakefield Press)

First published in 1913, this German novel is credited with helping found “German SF” as well as serving as an influence on German Dada and Expressionist writings. Its surrealism and fantasy pushed back against the dominant realism of the era. Episodic and hypnotic, the novel describes life on the planetoid Pallas where “rubbery suction-footed life forms with telescopic eyes smoke bubble-weed in mushroom meadows under violet skies and green stars.” There’s definitely an early ecological theme here, a sense of trying to create a new perspective. Intriguingly, the writer and painter Alfred Kubin created illustrations for the novel — yet another link between Scheerbart and the weird. (Kubin’s own classic novel, The Other Side, was reissued this year by Dedalus and if you haven’t read it you must run out and buy it immediately.)

All the Birds, Singing by Evie Wyld (Pantheon)

In All the Birds, Singing Wyld creates an unforgettable character in Jake Whyte, a woman with a troubled past who, in the present, lives on a farm she owns on a remote British island. The story of her encounters with a strange beast and neighbors she wants nothing to do with is interwoven with a narrative about the past that gradually delves farther and farther back in time. Wyld’s also not afraid to just give the reader the blunt, brutal truth. There are aspects of Whyte’s past — because of what’s been done to her and what she herself has done — that you get full-on, in detail. To describe them here would be spoilery, in that the life of the novel is in the moment and in the particulars of sometimes fairly brief scenes. But my point is that we begin the novel with a mystery about Whyte — who she is and why she’s now on the island — and on some level the rest of All the Birds, Singing is nothing but exploration of her character, a kind of clear-seeing that creates empathy even through the most disturbing sequences. The truly exceptional prose is supported by a vision for the novel’s structure that has both clarity and substance.

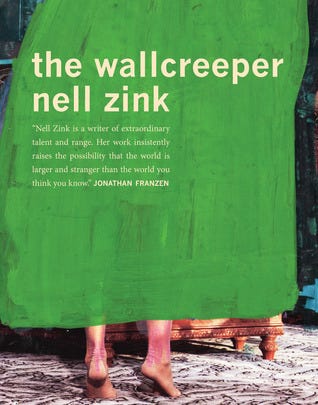

The Wallcreeper by Nell Zink (Dorothy Project)

Frank is not a proper noun in The Wallcreeper; it’s a way of life. But so is an inventive and layered approach to narrative. As this story of a woman, her husband, and encroaching commitments to other people and to environmental causes progressed, I marked so many pages because of an original turn of phrase or some stark assertion some other writer would have circled around…that I had to stop. For that reason, too, I’m not going to share any quotes because a huge part of the pleasure of the novel is encountering the surprises at the sentence level. Even as The Wallcreeper can be cynical, arch, and satirical about its eco-pushing characters, it contains a useful critique of certain approaches to environmentalism. A lot of what’s on display is utterly fearless writing.

***

photo by Kyle Cassidy

Jeff VanderMeer’s The Southern Reach Trilogy made Entertainment Weekly’s list of the Top 10 Fiction of 2014, in addition to the best-of lists of the Los Angeles Times, Buzzfeed, and many others.