interviews

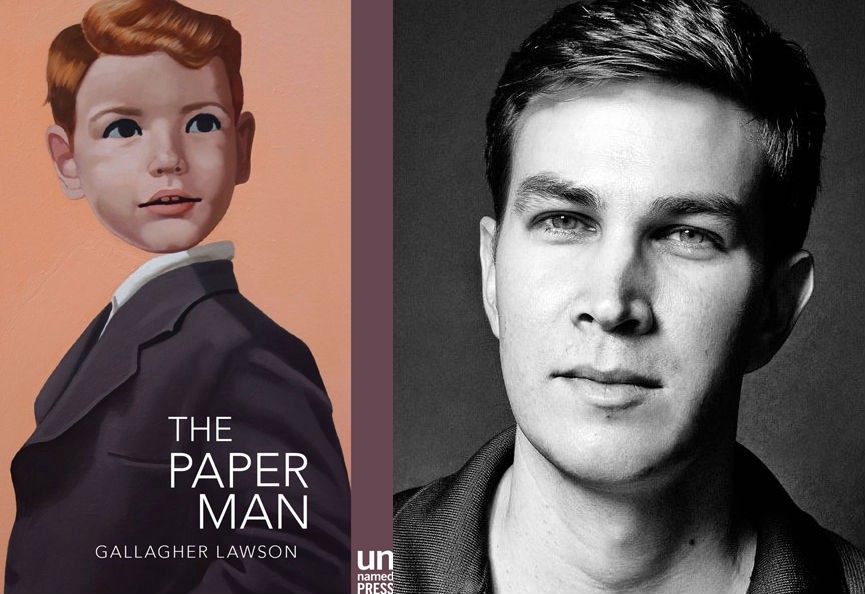

Looking Past the Variables, an interview with Gallagher Lawson, author of The Paper Man

Gallagher Lawson’s debut novel, The Paper Man, is almost Pinocchio in reverse. Michael is a real boy whose father transforms him carefully into a man of paper after a mysterious accident. In Lawson’s bildungsroman, Michael leaves his stagnant life in a rural area to travel to the vibrant, artistic city. But the city is dangerously full of decay and unrest. On his first day, Michael is in a bus accident caused by a dead mermaid in the road; he has to contend with the byproducts of political strife between the citizens. The city is both a haven for artists and a place where things decay, rapidly. In this allegorical tale, Michael’s corporeal form is a stand-in for art itself. Lawson gives voice to the artistic yearning to define creative existence.

Lawson spoke with me about creating his paper man, art and writing, and the power of symbolic writing.

Heather Scott Partington: Michael, the main character in The Paper Man, has an acute sense of his body in space. The book has a definite sense of physicality, even though Michael’s humanity is unique. Were there challenges in creating a paper person? Things you thought about as you created his sense of identity?

Gallagher Lawson: Lots of cool things were possible with a character whose body is made of paper, but yes, there were challenges. One big one was to find all the unusual opportunities where his body would cause a different response than a typical person — examples include talking with someone who occasionally spits, being in spaces that have a strong odor, and what to eat while at a pudding shop or diner. Then there were logistical challenges, such as his inability to heal from changes to his body, having limbs detached and reattached, and the danger of water. And of course, there was the challenge to keep all of these features in balance with someone experiencing very human emotions. I took all of these on as a chance to really flex my imagination, and made writing the book very exciting for me.

HSP: Michael is fragile, but so are many of the other characters he encounters. His world is one where there’s a lot of pain, and a constant sense of collapse. Was this to mirror the fear/concern your main character feels about the potential for damage to his body? What role does the outside world play in reflecting his inner conflict?

I was really interested in exploring how individuals fit or do not fit in an outside world that is undergoing a more massive identity shift.

GL: It’s more about the tension between being an individual versus being part of a group. Both the outside world and the characters are undergoing their own identity crises. While Michael is struggling to find a sense of autonomy and individuality in the city by the sea, the city itself is under threat from a northern government to annex it as their own territory. I was really interested in exploring how individuals fit or do not fit in an outside world that is undergoing a more massive identity shift. Is it selfish for a creative person to focus on their art and uncovering their individuality while their world is in a state of collapse? Or can those individuals create change in a society that is full of unrest? How do they influence or dictate each other’s identities?

HSP: Smells are important in this story — actually, the book is very visceral. Characters’ perceptions of all of their senses really influence their actions and the way they view the world around them. What was important to you about the way each character would experience life in the city?

GL: When you have a book that includes a man made of paper, a dead mermaid, and other unusual features, it really helps ground the story when you have lots of sensory details. I also react strongly to such details as a reader, particularly to smells. I tried to give a complementary emphasis of senses to the characters and their own interests. Maiko, a fur model, is very much about the tactile feel of things. Doppelmann, an artist, relies on vision to observe the world. Mischa, a woman from Michael’s past, is obsessed with how she is perceived and sensed by others. Some of Michael’s senses are dulled because of his condition, so it worked that he had a heightened sense of smell.

HSP: You’re an accomplished pianist, and the arts feature prominently in The Paper Man. Can you talk about the non-literary influences on your work?

GL: Great question. I like to think of this book as having a dialogue not just with other books, but other art forms as well. Visual art is a big influence on my work. This book was strongly influenced by many visual artists, particularly paintings by Francis Bacon, photographs by Cindy Sherman, and the biographies of Matisse and Gorky. As for music, while writing this book I was studying a lot of piano pieces by early twentieth century composers, including Rachmaninoff, Shostakovich, Prokofiev, Khachaturian, and Scriabin. I love that period because they were experimenting with using the piano as a percussive instrument. Much of their music has these harsh, dissonant sections bookending these beautiful, lyrical passages. I’m sure my impressions of these other art forms found their way into the book.

HSP: Many of the names in The Paper Man are similar. Michael, Mischa, Maiko. Adam and Doppelmann also seem to have an etymological significance that’s important to the story. Can you talk about how you named your characters?

GL: I don’t want to say too much about this, but yes, it was intentional to name the characters this way, and it was in the same vein as having a motif in music that is played in different keys and time signatures.

HSP: Since this novel is allegorical, what are your favorite allegories? What is it about this kind of story that speaks to us as humans?

What I really like about allegory, and what I think speaks to us as humans, is that it takes away specifics so that we can see deeper into ourselves.

GL: I’ve had a strong connection to allegories, fables, and fairy tales since childhood. As a kid, I loved the entire Oz series so much that I wrote my own series, The Land of Green Grass, which was about a bunch of insects living in the corner of my front lawn. Each little book featured one insect as the main character, and described their adventures in my front yard. Other favorites include The Mouse and his Child, Watership Down, The Unconsoled, and The Magus. What I really like about allegory, and what I think speaks to us as humans, is that it takes away specifics so that we can see deeper into ourselves. Writing allegories is a kind of laboratory for me. I want to look past the variables — such as named historical, cultural, political issues, or even the named power dynamics — and really get a glimpse at some of the roots and underlying motivations and desires we have as humans.

HSP: What is your reading process? What draws you to a book? What habits and routines do you keep when it comes to reading?

For fiction, I’m drawn to books that have something odd or unconventional about them. Often when I read a book I love, I go on a reading jag and try to read as much of the author’s work as possible. (Case in point: I’m currently gobbling up the translated books of César Aira.) While I found that the mornings are best for writing, I typically read in the evenings, and the best weekends include a long afternoon and evening spent with a book.