essays

Part 2: Dispatches from Dream City: Zadie Smith and Barack Obama

P

PART 1 of this essay is located here.

IV

But let’s return to Obama. In the essay “Speaking in Tongues,” originally a talk delivered shortly after Obama’s election, Smith discusses her acquired flexibility of voice, the consequence of imposing the Cambridge English voice “with its rounded vowels and consonants in more or less the right place” on the voice of her childhood home, working-class North London. She ruefully admits that the two voices have narrowed into one, the educated voice, and that people are in general suspicious of voice-shifters:

We feel that our voices are who we are, and to have more than one, or to use different versions of a voice for different occasions, represents, at best. A Janus –faced duplicity, and at worst, the loss of our very souls.

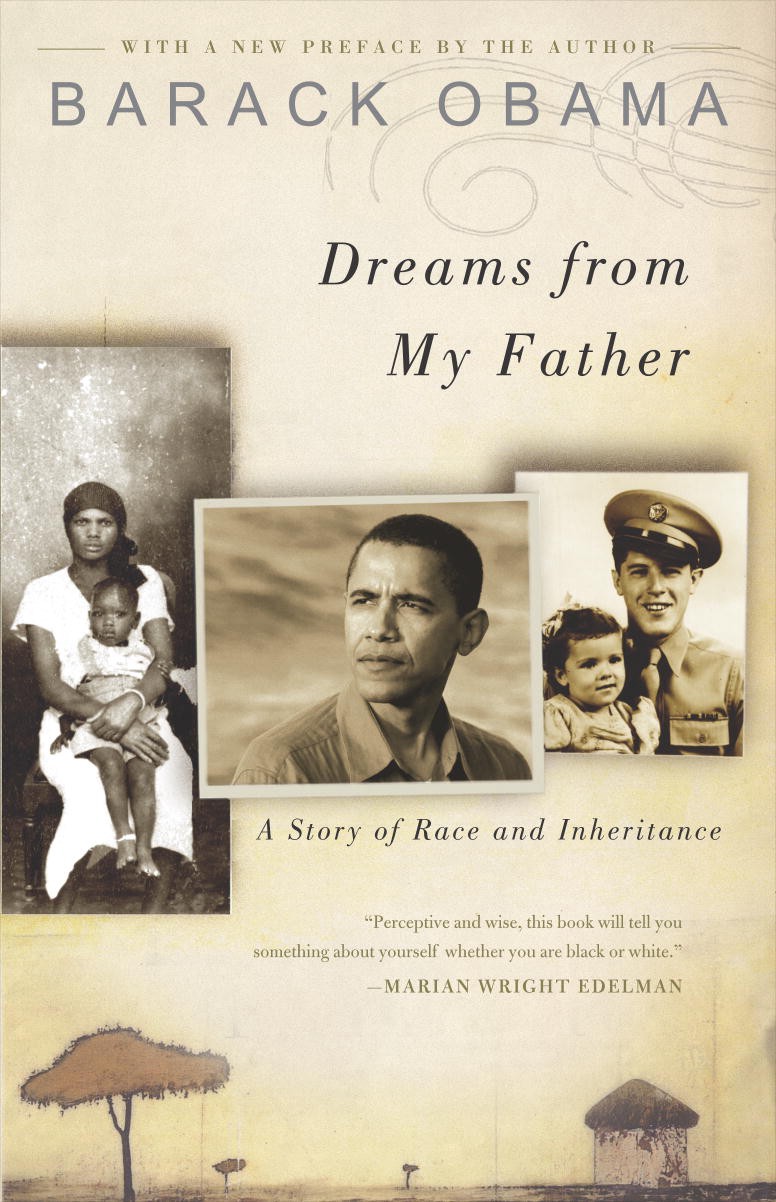

This leads to Shaw’s Pygmalion, nominally “the unambiguous tale of a girl who changes her voice and loses her self…undercut by the fact of the play itself, which is an orchestra of many voices, simultaneously and perfectly rendered.” Another orchestra of many voices is the skillful memoir of the new President, Dreams of my Father:

For Obama, having more than one voice in your ear is not a burden, or not solely a burden — it is also a gift.

She quotes Obama on his parents’ failed marriage: “I occupied the place where their dreams had been.” Occupying a dream space is the job of the movie star; another voice shifter was the Englishman Pauline Kael called The Man from Dream City, Cary Grant, who transformed his voice into a voice neither English nor American, neither posh nor working class. Everyone wants to Cary Grant, even I want to be Cary Grant, Grant was quoted as saying.

It is not hard to imagine Obama having that same thought;…hearing his name chanted by the multitude.

Everyone wants to be Barack Obama. Even I want to be Barack Obama.

Obama was born in [Dream City]. So was I. When your personal multiplicity is printed on your face, in a almost too obviously thematic manner, in your DNA, in your hair and in the neither-this-nor-that beige of your skin — well, anyone can see you come from Dream City…You have no choice but to cross borders and speak in tongues. That’s how you get from your mother to your father, from talking to one set of folks who think you’re not black enough to another who figure you insufficiently white.

Speaking in one voice to an audience in Iowa and in another voice to an audience in North Philly, is not just a necessary talent of the politician, it is also a way of insisting on the multiplicity that many of us feel.

That Obama would publicly criticize the black community and incur the wrath of Jesse Jackson “goes to the heart of a generational conflict…concerning what we will say in public and what will say in private.”

Here, it’s probably worth contrasting the pronouncements on race by Smith and those of America’s perhaps most famous biracial literary artist, August Wilson. The enormous difference between Wilson’s scorched–earth statements — expressing solidarity with the notorious anti-Semite and black separatist Amiri Baraka, refusing to let a white director film his play Fences, insisting, despite all the evidence to the contrary, that little has changed for Black Americans in the last fifty years — and the more equivocal views Smith gives can to some degree be accounted for by the difference between growing up in 1950s Pittsburg and 1980s North London. But the rest has to with a difference in temperament — the difference in temperament between the prophet and the mediator.

To me, the instruction “keep it real’”is a sort of prison cell…It made Blackness a quality each individual black person was constantly in danger of losing…

To keep it real means to speak in one voice, adhere to one set of prohibitions, which seems absurd, “not because we live in a post-racial world-we don’t–but because…black reality has diversified.”

For reasons that are obscure to me, those qualities we cherish in our artists we condemn in our politicians, In our artist we look for the many-colored voice, the multiple sensibility…the lack of allegiance in Shakespeare’s art…allowed him to do what civic officers and politicians can’t seem to: speak simultaneous truths.

Yes, but the lack of allegiance in politics means something different than lack of allegiance in art, doesn’t it?

Smith concludes on a cautious note of admittedly naïve optimism:

I believe that flexibility of voice leads to a flexibility in all things. My audacious hope in Obama is based, I’m afraid, on precisely such flimsy premises.

V

Flexibility of voice — or a good prose style, for that matter — is no guarantor of a good president. Lincoln had, like Obama, a wonderful y expressive prose style and a terrific sense of humor. Grant, by some estimates our greatest writer-president, was a disaster in office.

Almost halfway into Obama’s term, there are few people left who cherish the audacious hope Smith so eloquently expressed. When society has abandoned the center, and with it the belief in mediation, in compromise, in building bridges, in civility, then the fate of the mediator is not to bring opposites together but to be hated by both ends of the spectrum. Two years in, Obama looks — despite his self-awareness, his energy, his wit his nimble intelligence — less and less like Lincoln and more and more like Jimmy Carter.

It seems more likely every day that Obama’s legacy will be not for what he succeeded or failed to do in office, but for a work of the imagination; I don’t mean Dreams of My Father, though it’s possible that book will still be read when Obama is just a memory — I mean the presidential campaign. The campaign was as cynically crafted as any of Karl Rove’s, as full of wooly promises and focus-group tested buzzwords as any in recent times (in the saloon across the street from where I work, patrons who watched the presidential debates on the TV above the bar were given a free shot every time a candidate used the word ‘change’). Yet the campaign’s greater meaning — that if we don’t live in a post–racial America, large groups of Americans ardently wish that we did — will not be forgotten.

VI

Literature, of course, is different from politics. Few politicians can succeed in the long term without a broad consensus and a firm political identity. A writer, though, can change and change, and also fail and fail, and still find a way to seep into posterity. The canon is full of failures — works of literature that were ignored` in their own time and large parts of which are unreadable, awkward, wooly, obscure, lost in the fog of history.

VII

In ‘Two Directions for the Novel’, which is, like most of the literary essays in this collection, a winningly transparent act of self-persuasion, Smith suggests a Third Way for the bewildered novelist, “the path hewed by extraordinary writers claimed by both sides [i.e., the traditionalists and the avant garde]: Melville , Conrad , Kafka, Beckett, Joyce, Nabokov.”

VIII

“Much of the excitement of a novel lies in repudiation of the one written before,” Smith writes in ‘That Crafty Feeling.’ She continues,“My God, I was a different person!” “I think many writers think this, from book to book. A new novel, begun in hope and enthusiasm, grows shameful and strange soon enough. After each book is done, you forward to hating it (and you never have to wait long); there is a weird, inverse confidence to be had from feeling destroyed, because being destroyed, having to start again, means you have space in front of you, somewhere to go.”

Perhaps that path is the road to Dream City: the space where the writer doesn’t’ t self-consciously try to build a bridge between Forster and Wallace, but tricks herself into forgetting about both of them.

* * *

John Broening’s Column Note.

— John Broening is a chef and writer based in Denver, Colorado. His work has appeared in the Baltimore Sun, the Baltimore City Paper, Gastronomica, Edible Front Range, and the Denver Post, for whom he writes a weekly column about food.