writing life

Pineapple & Roasted Nuts: Ru Freeman On Sri Lanka’s Enduring Love Of Language And Books

We’ve asked some of our favorite international authors to write about literary communities and cultures around the globe. We’re bringing you their essays in a new ten-part series: The Writing Life Around the World. The sixth installment is by the Sri Lankan-born author Ru Freeman.

When I was a child, there was nothing much to do in my house in Colombo but write. Reading was desired, of course, but books were hard to come by, and that meant several things: my two older brothers and I read with great appetite, we fought over books, we memorized what we saw in black and white, and we dreamed of caravans, midnight feasts, puddings, and snow, things we had never experienced in our own lives. We begged for books from our friends at school, from neighbors our own age and much older. Books were passed around and packed away quickly into school bags as though they might be confiscated. They were brought out and read with deep pleasure. They were traded for favors of all kinds. The brother closest in age to me and I often exacted payment in pages of a book. The book you borrowed has only 253 pages, one of us might say, so you can only read 253 pages of the book I borrowed. And so we had to also turn into book thieves, risking fisticuffs in order to get at the final pages of the others’ book.

But writing. That was different. That could be done without servility, or becoming emotionally indentured to ones siblings. What I couldn’t memorize in its entirety, I wrote down in notebooks. Hooloovoo, a hyper-intelligent shade of the color blue, I took from Douglas Adams, as a child.

But why take all this quite so badly?

I would not, had I world and time

To wait for reason, rhythm, rhyme,

To reassert themselves, but sadly,

The time is not remote when I

Will not be here to wait. That’s why.

I wrote down in more elaborate script as a teenager in the back page of a notebook that I kept for gems like that one from Vikram Seth. This habit of being able to recognize the unique voice of writers I had no idea I would ever meet in person was one I could not shake. I recall noting — even as I speed-read the passages and questions on my ACT in Literature — the particular sentence that described our human fear of insects. I don’t remember the precise words, but the line noted that insects were the embodiment of our deepest human fears: the insides on the out, all spikes and gesturing, and the power of a determined collective. I left enough time at the end of the examination to jot down the two sentences on the back of a bus ticket in writing that mimicked, due to the constraints of space, the footprints of ants.

Much later, applying to colleges, when asked to write about a book that transformed my life, I reach back in time to another set of quotes that had made it into my notebook. They did not come from the great Russians I had by now read, nor from the English poetry and literature I had studied in my Advanced Level classes, nor from the Greeks whom I’d also read, but from William Peter Blatty’s The Exorcist. The two quotes, about good and evil, and about hope, defined a world view for me, one that continues to resonate in the way I live my life now. I wrote then, as a nineteen year old, about the place of things in a universe that had its own wisdom and reason. More than that, I wrote, quoting Blatty, that sobriety was vital in times of despair as well as in times of hope. I used his words without ever having seen the revenge exacted by a Fall on a Spring, or the Spring on Fall. It was the poetry and musicality of the words that gripped me. Those words made sense.

* * *

…there was a dictionary in the house to which my brothers and I were directed. We cursed and swore (in our elegant tongues), but we reached for it anyway.

There’s a particularity to the way language is acquired by a non native-speaker such as myself, and how it is manipulated. My English texts in Sri Lanka were full of the rudiments of basic English which were required for the entire school population, but at home I was immersed in a version so elevated from that kind of ordinary usage that there was little to do but learn how to become conversant in it. My parents spoke that way, as did my brothers, and therefore so did I. There was no value placed on knowing the latest information on pop stars, though a working knowledge of politics was expected within the family. We did not own a functional pair of scissors, band-aids (sticking plasters) were bought one at a time and only when required, and shopping in general was undertaken for only the most necessary items, but there was a dictionary in the house to which my brothers and I were directed. We cursed and swore (in our elegant tongues), but we reached for it anyway.

This was our underlying message: what we needed to know could be found in books, and if we failed to find our answers there, we would at least have acquired the language with which to ask for help from smart adults. And since this acquisition was so varied, our sense of its usage was correspondingly without limits; there was an internal rhythm to our understanding of the English language that did not seek to obey any single aesthetic, but instead let our intuitive sense of the world unfold on the page however we wished.

* * *

During those years, Sri Lanka had no tradition of public readings of work in English, though those who wrote in Sinhala and Tamil had their own, multitudinous audiences. As such, we, along with our peers, performed for private audiences in full length theater productions or during examinations where we declaimed the words of others rather than our own. Pulsing beneath what was taking place among those like me who wrote in English, was an entirely different scene: one where Sri Lankan writers saw their own work performed on stage. For those who wrote in English, publication translated into collections of poetry rather than prose, though there were always exceptions, and that work was assigned for study in university. It was, in other words, a more cerebral activity, rather than one that included the out-loud utterance.

It has been fascinating to discover, then, the more recent establishment of festivals of literature in Sri Lanka and, more importantly, readings of new work, as well as the local publication of fiction in English. The Galle Literary Festival is known beyond Sri Lanka’s shores and has had its share of critics for its lack of inclusion of literature in translation, but it is a festival that has brought international writers to Sri Lanka. More than that, though, are the smaller local festivals that have taken on the matter of engaging with literature in a way that continues a cultural tradition of respect for language and books. Of these, Annasi & Kadala Gotu (which translates into pineapple and hand-held cones of roasted nuts), is perhaps the most interesting. It spanned just one day, but included panels of people discussing literature and the creative process in all three languages, Sinhala, Tamil, and English. Its very name is an acknowledgement of a particularly local love for nutritious, delicious, and completely addictive street food, and an attempt to demystify literature and the literary culture.

It stood to reason, then, that the organizers of that festival were intrigued to hear of an endeavor that I have been pursuing along with my brother, Malinda Seneviratne (also a writer, journalist, poet, and winner of both the Gratiaen Prize for Literature in Translation in 2013, and the Gratiaen Prize for Poetry in 2015, established by Michael Ondaatje), the establishment of an international festival of literature in translation, which we called IF/LIT. Earlier this year, in the wee hours of a morning, I skyped in from the U.S. on an afternoon gathering in Colombo. Assembled there was my brother, two young men who were active in the local literary scene, Rick Simonson from Elliott Bay Book Company who was in Sri Lanka after speaking at the Jaipur Literary Festival (JLF), visiting my father, and a group of Sri Lankans, all women, who had been brought together by a former school-friend of mine. The most interesting thing about this group was that none of the Sri Lankans (other than my brother) were writers, but they were all extremely well-read, continuing into this present day our tendency to place great value on the worth of books. Further, all of the women were in positions of power, most of them heads of private corporations from hotels and tourism to exports and finance, and all of them active patrons of the arts. Even more importantly, they were committed to sharing their love of learning of the world through its literature with as wide an audience as was possible, and willing to volunteer their time to make that possible.

What were they doing immersed in books? Simply this: they loved literature.

I don’t know if that drive to invest so personally in literature is unique to Sri Lanka, but I can say unequivocally that it is rare here in the U.S. where I live now. I was somewhat transfixed by that conversation, by the energy in that beautifully appointed room, by the intense practicality regarding the logistics of putting such a festival together, which at no point diminished the bright enthusiasm for and embrace of the festival itself, an ambiance that harkened back to those Blatty quotes I’d jotted down. This summer when I was in Sri Lanka I met with the young organizer of Annasi & Kadala Gotu. He made an appointment with me, sat bolt upright in a chair, asked questions and took notes. He made suggestions informed by considerations that I had not stopped to think about, and explained which people could take on which tasks in putting a festival of this magnitude, our IF/LIT, together. The person who began the festival he had just completed was an airline pilot, a non-writer. He himself was a computer programmer. His friends who would handle publicity and tickets and every other conceivable detail that goes into producing a festival were mostly engineers and accountants. What were they doing immersed in books? Simply this: they loved literature. They loved literature because they had been taught, as we had been taught, about the significance of the imagination, and of the way our minds expanded through the simple act of inhabiting other people’s reality.

* * *

He had lost none of that particularly subtle language of regard, a lexicon that is a blend of a quintessentially Sri Lankan character gilding this foreign tongue.

During a recent visit that took place in the wake of JLF, at which I’d spoken with him, I attended a book launch for Romesh Gunasekara (Noontide Toll and others). The event took place at Barefoot, a favorite haunt of expatriates and well-shod Sri Lankans, and the whole evening had an elegance that was unusual in my experience; readings in America, with the notable exception of Seattle, seem largely unpredictable. This launch took place in the open-air courtyard, with tables decorated with lamps and flowers, a porch provided the stage-setting for the reading, and books were bought and signed before a word was read. The whole event concluded with hors-d’oeuvres and red and white wine served by wait-staff. An airy reverence hung over the assembled. Most significantly, I noted the way in which the London-based author of the hour spent time with the guests who were almost all known in some fashion to him or to his family. He chatted a little to Shyam Selvadurai and me, both of whom he knew well, but I noticed the care he took to pull up a chair and sit with my father, himself a poet and reviewer. I listened as they reminisced about various Sri Lankan writers, their own families, and conversed about books read and those yet to be written. They were of a different time, there was mutual respect, but my father was the older man and Romesh had lost none of the reverence reserved for those who served not only as friends but as teachers, whether or not they stood in front of chalkboard in classrooms. He had lost none of that particularly subtle language of regard, a lexicon that is a blend of a quintessentially Sri Lankan character gilding this foreign tongue.

* * *

…we were in agreement: our country, despite all that had ravaged it, still pulsed with that same yearning for the benediction of books that we had once experienced…

Many months later I heard Romesh’s voice again. He was back in London, and I was back in the United States, and we were connected on air on a BBC program, being interviewed by Rana Mitter. It was a program devoted to a conversation with writer Tony Harrison, the 2015 winner of the David Cohen Prize for a body of work. On a program devoted to an artist who welcomed political debate on topics ranging from the Persian Gulf to Bosnia, Mitter felt it would be interesting to have two writers from Sri Lanka, a country of much turbulence, and recent peace, to speak about our experience writing of it. Over the course of the program, I listened to Romesh’s soothing inflections, and to my own much less mellow delivery. We were of different generations, a world apart, speaking about our nation of origin. We left it off air, discussing IF/LIT, and the importance of literature. We were not that different. We had read different books, growing up, and our phrasing was correspondingly divergent, but we were in agreement: our country, despite all that had ravaged it, still pulsed with that same yearning for the benediction of books that we had once experienced, and we, having been blessed by that culture, saw with intimate clarity the importance of continuing to participate in the vitality of a well-read citizenry. I took off my headphones and headed to Miami where I was due to speak the next day. I took my country and my countrymen with me, that unique communality that we bring to our embrace of the written word, the way in which poetry and stories are so universally regarded as being essential to human life.

About the Author

Ru Freeman’s creative and political writing has appeared internationally. She is the author of the novels A Disobedient Girl (Atria/Simon & Schuster, 2009) and On Sal Mal Lane (Graywolf, 2013), a New York Times Notable, and Editor’s Choice Book. Both novels have been translated into several languages including Italian, French, Hebrew, and Chinese. She is the editor of the ground-breaking anthology, Extraordinary Rendition: American Writers on Palestine (2015). She blogs for the Huffington Post on literature and politics, is a contributing editorial board member of the Asian American Literary Review, and has been a fellow of the Bread Loaf Writers’ Conference, Yaddo, Hedgebrook, and the Virginia Center for the Creative Arts. She is the 2014 winner of the Sister Mariella Gable Award for Fiction, and the Janet Heidinger Kafka Prize for Fiction by an American Woman.

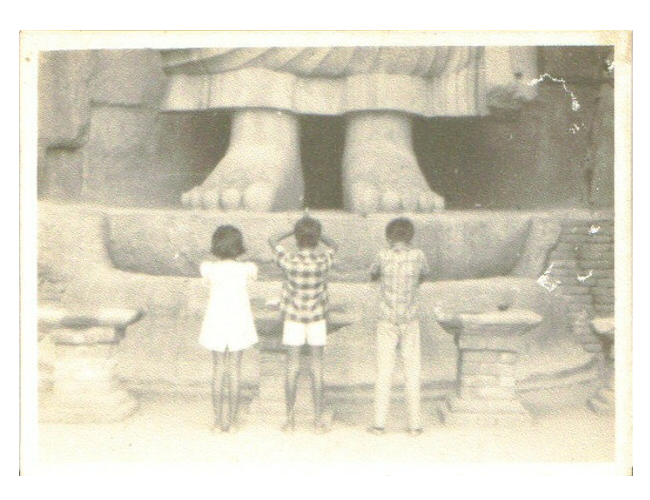

The photographs accompanying this piece were provided by Ru Freeman and may be found, with captions, at her website.

You can find all the essays from The Writing Life Around the World at Electric Literature.

The Writing Life Around the World is supported by a grant from the Council of Literary Magazines and Presses and the New York State Council on the Arts.