Books & Culture

REVIEW: Bark by Lorrie Moore

In “Debarking,” the opening story of Lorrie Moore’s latest collection, Bark, recently-divorced Ira worries that he may be too critical of his new love-interest: “Either she was stupid or crazy or he was already being too hard on her. Not being hard on people — ‘You bark at them,’ Marilyn [his ex-wife] used to say — was something he was trying to work on.” This, coupled with the story’s title, marks the beginning of a play-on-words that Moore sustains throughout the entirety of the wildly anticipated collection. Bark contains numerous references within its pages, from the three poem excerpts chosen as epigraphs, to various characters’ dogs, to the description of the cerebral cortex. In these stories, bark (or a bark, whether human or canine) is an aggressive cry, a warning call, and a protective layer. It is a method of self-defense.

Moore’s short fiction explores the myriad ways that we, as Americans and as humans, attempt to defend ourselves from both personal and political vulnerabilities.

Long-time fans of Moore’s work will not be surprised to find the characters in Bark shielding themselves with the armor of humor, wit, and wordplay. Her signature bon mots are plentiful, her parenthetical asides are peppered with exclamation points, and there’s no shortage of hilariously outlandish metaphors. About Ira’s aforementioned love-interest, she writes: “The nipples of her breasts were long, cylindrical, and stiff, so that her chest looked somewhat as if two small sink plungers had flown across the room and suctioned themselves there.” These inimitable one-liners have helped build Moore’s reputation as a funny writer ever since her first story collection, Self-Help, was published in 1985. Of course, the most comical lines almost always hint at a bleaker worldview just below the surface. In Bark’s closing story, “Thank You For Having Me,” the divorced, single mom at a wedding describes the bridesmaids’ pastel dresses in terms of their pharmaceutical counterparts: “One the light peach of baby aspirin; one the seafoam green of low-dose clonazepam; the other the pale daffodil of the next lowest dose of clonazepam.” Moore pushes the dark humor to extremes that may irritate certain readers, but

her dagger-sharp witticisms are in top form in this collection — they’re not just indicative of her characters’ underlying sorrows, but also uproariously, side-splittingly funny.

When it comes to love, especially for women, the humor in Bark is darker and the prospects grimmer than ever before in Moore’s fiction, which is quite dark and quite grim indeed. “Paper Losses,” about a divorce after twenty years of marriage, begins with hatred — “Although Kit and Rafe had met in the peace movement, marching, organizing, making no nukes signs, now they wanted to kill each other” — and follows Kit along her journey to hopeless resignation: “A woman had to choose her own particular unhappiness carefully. That was the only happiness in life: to choose the best unhappiness.” Women are incredibly cruel to other women, criticizing each other’s choices as too feminist or not feminist enough, exhibiting embarrassing displays of jealousy and resentment, and intentionally deluding each other about current relationships:

“Romantic hope: from where did women get it? Certainly not from men, who were walking caveat emptors. No, women got it from other women, because in the end women would rather be rid of one another than have to endure themselves on a daily basis. So they urged each other into relationships. ‘He loves you! You can see it in his eyes!’ they lied.”

Pessimism regarding romantic love has been constant in Moore’s fiction but in Bark, she enhances the hopelessness we feel for her characters by experimenting with nonlinear narratives.

Several stories take sudden, giant leaps forward in time to provide glimpses of devastating futures.

“Subject to Search,” one of the book’s most overtly political stories, features an American woman in France meeting her lover, a US intelligence agent, for lunch. He has just learned he must immediately leave the country (and, by extension, her) due to recently reported “torture incidents involving American troops at a Baghdad prison.” In the midst of her confusion and disappointment, the narrative skips ahead to reveal the truly heartbreaking future that awaits this couple. Although readers are eventually left with an earlier, more hopeful moment in this relationship, it’s tinged with a sense of foreboding. In seemingly pleasant moments, there exists the inevitability of a downturn. For the unmarried, the recently divorced, and even those currently dating or married in Bark, the likelihood of finding and sustaining love seems improbable at best, impossible at worst.

Where Bark really distinguishes itself from Moore’s previous work is in this melding of the personal and the political — the way political events both shape and reflect her characters’ personal concerns. The real world feels more tangible here than in some of Moore’s previous collections, in which characters sometimes seem to be playing out their personal dramas in a small vacuum. The environment in these stories feels more sharply rendered. Simple details, like a truck speeding by with a NO HILLARY NO WAY sticker affixed to its bumper, both contextualize and complicate the stories’ settings. And while the material of Moore’s fiction has frequently been described as domestic, as in “relating to family,” another definition of domestic, “of the internal affairs of a nation,” is also an apt descriptor. These characters would not be the same lovers, spouses, or divorcees if they were not also Americans living in these unique moments in American history.

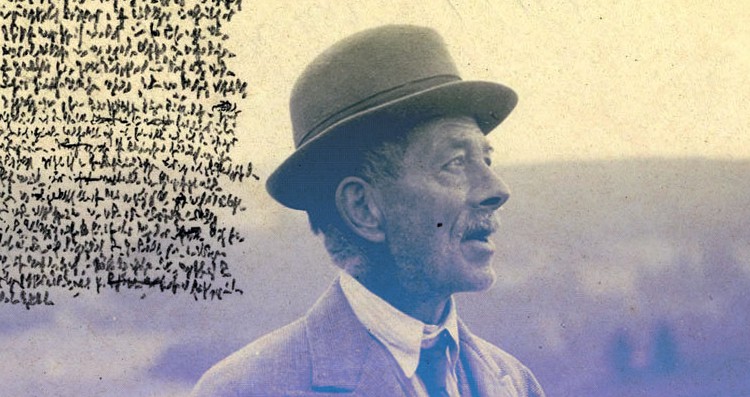

Of course, the ways in which various administrations’ foreign and domestic policies impact American citizens is not a new theme in Moore’s writing. In a 2005 interview in The Believer, she discussed the relationship of her writing to politics, explaining that she was “interested in the way that the workings of governments and elected officials intrude upon the lives and minds of people who feel generally safe from the immediate effects of such workings.” In “How to Become a Writer,” one of her earliest and most frequently anthologized stories, a character finds herself at a loss for words when she attempts to write about the physical and mental damage her brother suffers after returning from Vietnam. And the second half of Moore’s 2009 novel A Gate at the Stairs revolves around the devastating loss of the main character’s brother, Robert, an Army recruit killed in Afghanistan. However, unlike previous collections in which political events appear in only a few stories, and A Gate at the Stairs, which spans several years, the stories in Bark work together to comprise over a decade of significant events in the American political landscape. Arranged in the chronological order of their publication dates, they span the decade between 2003 and 2013, covering everything from the US invasion of Iraq, to the torture at Abu Ghraib, to Obama’s election, to the economic downturn. In “Foes,” which was originally published in The Guardian just days before the 2008 election, a liberal writer named Bake McKurty gets into a political argument with a self-proclaimed “evil lobbyist” seated next to him at a literary fundraiser in DC. When the lobbyist reveals startling information about how the events of 9/11 impacted her personally,

Moore draws attention to the ways that humans (whether they be foes, friends, or lovers) often fail to understand and have compassion for one another due to their own fear-based self-defenses.

As an author, one of Moore’s most distinctive and admirable qualities has always been her own defensiveness. In today’s publishing world, as many authors (whether by choice or necessity) join Twitter, post on Tumblr, and agree to every proffered interview and engagement in order to promote their work, Moore remains relatively quiet. She consents to few interviews and when she does, refuses to respond to questions that annoy her. In fact, as she fields questions about her work and writing life,

one often gets the sense that she’s engaging in an act of resistance

. Rarely, if ever, has she been comfortable talking about her current writing projects, and she certainly becomes indignant with any insinuation that her fiction may be thinly-veiled autobiography. “A writer can’t control the reception of one’s work,” she said in The Believer in 2005, “or the perception of its author — as much as one would like to. You just have to put on your helmet and boots and get out your pen.” Bark is an excellent example of one of the best contemporary writers in America doing just that.

So, what do we do when we are faced with a close friend’s death, a crumbling marriage, a child’s illness, a terrorist attack? How do we go on living despite loneliness and pain and sorrow? How do we continue to live in this country when we disagree strongly with its policies? Moore does not provide answers in Bark. Instead, she has written a vital work of literature that holds a mirror up to the American public, showing us exactly what we have been doing: creating elaborate suits of armor, isolating ourselves as a means of self-defense, and barking — perhaps so loudly that we can hear nothing else.

by Lorrie Moore