essays

“Soft Grey and Curled Fetal”: Read an Essay by Alexandra Reisner

“Soft Grey and Curled Fetal”: Read an Essay by Alexandra Reisner

Essay: Small Bodies, by Alexandra Reisner

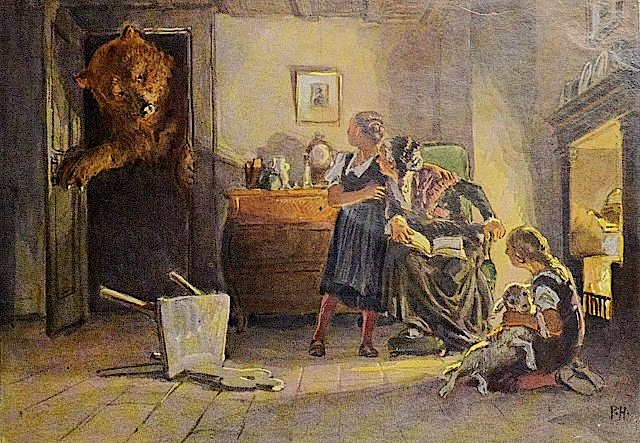

A six-year-old child’s eyes are set only about three feet off the ground, which is probably why the girls saw it first. I was bringing up the rear on the walk from the tennis courts when I noticed two or three of them crouching. “What is it?” I asked as I knelt to see what they saw.

It was a mouse — a baby — on its side in the grass. Its head was touched with blood but still its sides rose and fell. “What should we do?” I said, in part because it seemed as good a time as any to let them test their fledgling agency, in part because I had no idea myself.

“We need to save it!” shouted Rebecca*, a thin yet surprisingly muscular spider monkey of a child with long bronze hair and long bronze legs she used to climb all over my back. The other counselor, Diana, and I were sure she’d be a gorgeous terror far too soon.

We made a circle around the mouse while the girls shouted “Help!” and I looked on half-serious, so no one would mistake it for a real emergency, until someone important, signaled by a walkie-talkie clipped to cargo shorts, showed up and radioed for a maintenance man. He came, a teenager in a baseball cap and blue shirt with the word STAFF printed across the back, steering a golf cart with garden-gloved hands. The girls, gathered in a bunch at my knees, looked up at me as I explained to him: 1) We found a mouse, 2) it is living and it is hurt, and 3) is there anything you can do, please? The boy, perhaps a year or two younger than my nineteen, looked bored. Without a word he lifted the mouse, its thread of tail pinched between his thumb and forefinger, and flung it into the trashcan on the back of his cart.

•

I worked as a counselor at this standard-issue suburban day camp only once, in the summer of 2004. I had been a camper there for three summers, from when I was twelve until I was fourteen. These were the prime awkward years, scored by the dance hits of Ace of Base and La Bouche — summers of sweat-slicked idleness that served as an interlude between earlier and later years at an art camp where I learned to play classical guitar and developed hopeless unrequited crushes on boys who later, without exception, came out as Zionist or gay.

I had come home to live with my parents on Long Island in between my freshman and sophomore years of college. I was offered a job at a Bloomingdale’s in a mall named for one of my least-favorite poets, but I let my mother convince me that women who worked in department stores were catty and would make my life miserable, and so I declined. Instead, I took a night job at a record store, making half as much money as I would have at the department store, and a job at the camp making half as much as that. Along with Diana and two other counselors, I was placed in charge of the Flamingos, a baker’s dozen of five- and six-year-old girls.

Diana and I ate camp lunches while other counselors packed restaurant-style lettuce wraps redolent of low-carb diets and homes with staffed kitchens. Many were so thin that a pigeon-toed camper in a group challenging ours in kickball once asked if I, by contrast, was expecting a baby.

Among our girls, Corey and Emma were the group’s de facto leaders. Already cliquish and fashion-conscious at six, they carried miniscule handbags and spent free time brushing their hair. Corey was the spitting image of her mother, a sunbaked and sinewy blonde employed as the head counselor of another group. Looking at her made me think of tennis. The facility with which Emma lied was so remarkable that I wondered whom she took after. Her face never betrayed any hint of remorse. Another girl, Giada, had a family who might have encouraged her precociousness too much. When a music teacher asked who her favorite artist was, by which she’d meant pop music group, Giada answered, “David Hockney.”

Alexa, broad-faced and freckled, was beautiful like Rebecca but quieter in it, with a hum of a voice and gentle presence. She shied away from the other girls, clinging instead to Diana and me. We indulged her at first because she reminded us of our lonely childhood selves, but I began to worry that she wasn’t going to make any friends. I pulled away, but that only meant she cleaved to Diana ever more fiercely, and the parents tipped her most at the end of the summer.

I took Jordan, swarthy and strange, to the infirmary once. We walked back hand in hand to join the rest of the group for dismissal. I stopped at a flutter of tiny wings and said, “Look, a beetle landed on you!” Neither of us made any effort to brush it off. She glanced calmly down at the iridescent shell hooked to her arm’s terrain and then back up to tell me, as if it made perfect sense, “That’s my favorite time of day.”

•

I don’t remember how we found out. The camp directors may have called the head counselors over and asked them to tell the rest of us. It may have spread in murmurs. I do know that instead of releasing our campers to their buses all at once that day, we were asked to each take a few girls and deliver them over, one by one, into the care of the drivers who brought them to camp each morning and home every afternoon. I had Alexa with me and I took her last because she wanted to hold my hand the longest. By the time we reached her usual bus, the driver was pacing. The other children were already onboard, waiting. She grabbed the child up in a hug and swung her onto the bus. “I was so worried!” she said to both of us, and then only to me, “I heard it was a little girl.”

It was a little boy. Not much earlier that afternoon, as another group sat under a tree awaiting dismissal, a several-hundred-pound limb — appearing healthy from the outside but rotted through within — broke off and fell from a cherry tree. It scraped up a few children, including an eight-year-old girl. It killed her brother, seated beside her, age four.

•

The following morning, the staff gathered in the lunch area. We awaited the arrival of a children’s grief counselor, called in to speak with anyone who needed it. There was a man there with one sleeve of his shirt pinned up, empty. Someone approached him to ask if he was here to talk to the kids — reading the absence of his arm as a sign he had survived some trauma, certifying him an expert on loss — but he was only another counselor’s boyfriend, stopping by to drop off the lunch she had forgotten at home.

As the children came off their buses, we gathered them in the usual attendance spot on the basketball courts. At the therapist’s behest, the art department had given us construction paper and crayons. We were asked to ask the children to draw something they remembered from the previous day at camp. Giada and a few others drew what they had heard about at home and then imagined — what they could not have remembered because they had not seen: a child pinned beneath a broken tree. They drew red for blood. Most of the girls drew the swimming pool or the kitchen from cooking class or tennis balls. Rebecca — and I wanted to take her up in my arms then — drew (soft grey and curled fetal) the poor living mouse.

* Children’s names have been changed.