Books & Culture

Space Tourism in Modern Storytelling

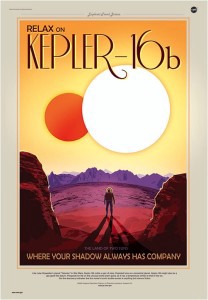

In the sight-seeing poster for planet Keplar-16b, a traveler in a space suit stands silhouetted before a purple and rose-colored desert. Craggy mountains rim the horizon. Orange and white orbs illuminate a yellow sky. “The land of two suns,” the poster explains, “where your shadow always has company.”

The image fronts as promotional material for a hot, long distance vacation booked through Exoplanet Travel Bureau, a faux tourist agency specializing in interstellar vacations. In fact, Jet Propulsion Laboratory, a branch of both NASA and the California Institute of Technology, released the image. The institute is “dedicated to the robotic exploration of space,” and their projects include monitoring weather by satellite, determining the properties of gaseous planets, and the 2003 launch and 2004 landing of the space rover Opportunity on Mars.

Since January of last year, JPL has released fourteen stunning, futuristic posters, depicting the treacherous beauty of interplanetary life. Each image undermines fundamental assumptions. In the poster for HD 40307g, a skydiver free falls through the atmosphere of a “Super Earth.” “At eight times the Earth’s mass,” the poster narrates, the planet’s “gravitational pull is much, much too strong.” The poster for Keplar-186f, a planet that orbits a cooler and redder sun than ours, disrupts expectations about the nature of light. In this one, a space-suited couple admires crimson foliage. “If plant life does exist on a planet like Kepler-186f,” a caption explains, “its photosynthesis could have been influenced by the star’s red-wavelength photons, making for a color palette very different than the greens on Earth.”

The retro-styled series takes its inspiration in part from the Kepler Project — NASA’s mission to survey our region of the Milky Way and locate planets similar to Earth. Kepler’s website explains, there is “clear evidence for substantial numbers of three types of exoplanets; gas giants, hot-super-Earths in short period orbits, and ice giants. . . The challenge now is to find terrestrial planets . . . one half to twice the size of the Earth . . . in the habitable zone of their stars where liquid water and possibly life might exist.” Left unsaid is the distant dream of interplanetary colonization, where scientific research meets sci-fi fantasy. So far, Kepler’s closest Earth-match is Kepler-452b, a planet 60% larger than our own with a 385-day orbit around a Sun-like star. Unfortunately, for wannabe visitors, this exoplanet is 1400 light years away.

While space tourism is futuristic, the style of JPL’s new posters harkens back to previous decades. The colors range from day-glo lime and orange, to gauzy hues of peach. The styles, too, are bygone, recalling Art Nouveau’s organic curves, Mid-Century’s precise lines, and the tie-dyed optimism of the 60s and 70s. The effect is more nostalgic than revelatory, depicting a golden age for interstellar imagination, a time when the future felt more playful and less apocalyptic.

The effect is more nostalgic than revelatory, depicting a golden age for interstellar imagination, a time when the future felt more playful and less apocalyptic.

Many of today’s pop culture depictions of space travel aren’t whimsical. No longer concerned with the anthropological details of alien species and exotic terrain, popular narratives focus instead on the survival of humanity and the long-term viability of Earth as a home. Consider the recent blockbusters Interstellar and The Martian, which both balance a desperate need for discovery with the psychological burden of participation in a mission likely to fail. Unlike the adventurers on holiday depicted in JPL’s posters, these films feature solitary pioneers confronting the abyss of time and space. The stakes couldn’t be higher. In Interstellar, Earth is barely habitable, devastated by drought and dust storms. The best possibility for humankind’s survival depends on a retired pilot’s ability to navigate a wormhole, locate a new home planet, and transmit its location back to Earth. In The Martian, astronaut Mark Watney is separated from his crew during a dust storm and presumed dead. Stranded on Mars, he must adapt to his new environment, keeping his body and spirit alive until he’s rescued. In each film, the heroes’ inner landscape, a predictably lonely terrain, is reflected perfectly by their surroundings, which are hostile and desolate. The protagonists are literally and metaphorically lost in the nothingness.

Unlike the adventurers on holiday depicted in JPL’s posters, these films feature solitary pioneers confronting the abyss of time and space. The stakes couldn’t be higher.

Aurora, the newest novel by science fiction guru Kim Stanley Robinson, vastly expands the narrative timeline of intergalactic travel. The heroine, Freya, grows up aboard an intergenerational starship heading for the star Tau Ceti. 160 years and seven generations into the journey, the crew has nearly arrived, and the problems they face are as philosophical as they are practical. Reaching their destination means establishing new means of survival and reshaping the mythology that give purpose to human life. Over a breakfast of strawberries, Freya’s father proclaims, “we are thrust out of the end of [an old] story. Forced to make up a new one, all on our own.”

The recently translated sci-fi novel Another Planet for Rent by the Cuban author Yoss further estranges our planet. Instead of a fabled homeland for far-flung voyagers, Earth is the destination. Alien tourists called xenoids have populated the blue planet. After witnessing humankind’s inept efforts to protect natural spaces, the xenoids take on the project themselves, enslaving humans mentally, physically, and sexually. Flipping the script on colonial narratives, Another Planet positions its protagonists as indigenous Earthlings rather than intergalactic saviors. Humans are the obstacle in an alien species’ narrative about stewardship and travel. The prospect is humbling. Our cosmological destiny may lie beyond our control.

Shifts in the way we imagine space travel come in part from NASA’s change in focus. Unlike the Apollo days, when the Cold War inspired large investments in rocket science and the race to the moon, NASA receives a significantly smaller portion of federal funds (less than .5% of the federal budget), which it divides between space exploration and researching Earth. Unlike the Apollo Missions, NASA’s recent work monitoring melting ice caps, rising oceans, and extreme weather events is sobering. Rather than inspiring patriotism and wonder, understanding the mechanisms and consequences of climate change means acknowledging a potentially catastrophic future.

Spaceship Earth, as Buckminster Fuller dubbed our planet in 1967, is near a tipping point. The accumulation of greenhouse gases in our atmosphere is pushing natural ecosystems towards unstoppable positive feedback loops that could spike the rate of planetary warmth. Once these processes begin, they may be impossible to stop. Melting permafrost will release stores of methane, a greenhouse gas that traps as much as 100 times more heat in the atmosphere than carbon dioxide. Shrinking ice caps will expose more of the ocean’s dark surface, which absorbs rather than reflects heat. Drought will damage rainforests, including the Amazon, one of Earth’s most important carbon sinks, and bushfires will decrease the carbon storage capacity of forests. In each scenario, a symptom of climate change becomes an engine, releasing greenhouse gases and fueling atmospheric warming.

Spaceship Earth, as Buckminster Fuller dubbed our planet in 1967, is near a tipping point.

Interplanetary life is still a far off dream, yet anxiety about Earth’s future imbues this research with new gravity. Rather than focusing on discovery, popular culture reflects an increased concern with the logistics of space travel: what psychological challenges will voyagers face during decades long missions to reach a destination; can travelers use asteroids to stock up on water and fuel; can astronauts have sex in space; can women give birth in zero gravity?

These practical questions give way to unsettling existentialism and thrilling narrative possibilities. The scale of the universe is unfathomable. What does it mean to be a speck in the infinite? Do specks have the right to colonize new planets? Will life on a new planet cause adaptations that fundamentally alter our species? To what extent would we include plants, animals, bacteria, fungus and viruses in resettling? Which humans would go and which would stay behind? What are the consequences of failure? Of success?

Numerous stars, planets, asteroids, and nebula populate our galaxy, but the volume they occupy is dwarfed by the emptiness that surrounds them. Because the distance between solar systems is so great, without cryogenic sleep, space travel would entail almost no sightseeing and plenty of shuttling through the nothingness. In other words, exploration beyond our solar system requires conquering not only the third dimension, space, but also the fourth dimension, time. Heroism means confronting aging, mortality, and boredom.

A recent breakthrough suggests how much we’re learning (and how little we know) about the nature of time. On Thursday, February 11, physicists triumphantly announced the first ever detection of gravitational waves. Produced by colliding black holes, these waves vibrated a pair of L-shaped antennas, a precise, highly sensitive arrangement of lasers and mirrors, in Washington State and Louisiana. The significance of this discovery is epic, fulfilling a prediction in Einstein’s 1916 general theory of relativity, which postulated that space and time are not fixed but mobile, capable of jiggling, curving, stretching and collapsing.

Rather than mapping the known world, as geographic exploration does, discoveries about the relationship between space and time magnify our perception of what we don’t know. Knowledge is infinite. When we glimpse the expanse of what’s unknown, the wormhole of imagination can be an insufficient processor.

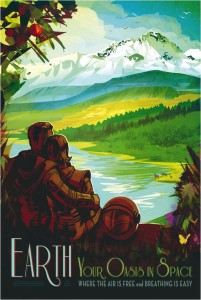

In the new JPL poster series, there’s only one image that features human tourists relaxing in the atmosphere with their astronaut helmets off. Looking out across a river at snow-capped peaks, a couple leans into each other. “Your oasis in space, where the air is free and breathing is easy,” the poster reads. After perusing drawings of the liquid ethane and methane lakes on Saturn’s moon Titan and the salt-water oceans beneath the icy surface of Jupiter’s moon Europa, fresh air, a (relatively) non-toxic environment, and just the right amount of gravity are nothing to take for granted. The miracle is that we’ve already arrived. While space exploration is awe-inspiring, perhaps the best lesson NASA can teach us is appreciation and stewardship for the home we already have, the planet we call Earth.