interviews

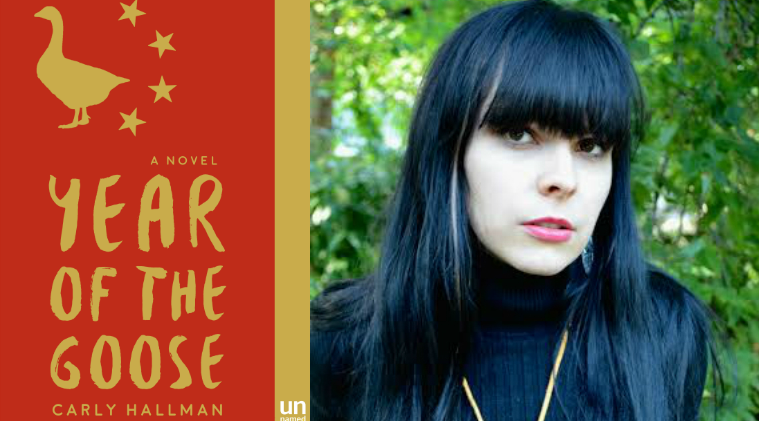

Ten Steps Further: A Conversation with Carly Hallman, Author of Year of the Goose

Carly Hallman’s debut novel, Year of the Goose (Unnamed Press 2015), is the kind of wonderfully unhinged and unencumbered book that resists categorization. It is at once a deft satire of contemporary China and popular culture, and a dizzying, absurdist romp. We are thrown into a world of hair tycoons, heiresses and pseudo-celebrities, diet camps turned into gruesome affairs, and monks turned into talking turtles. The eponymous goose, a national icon and symbol of the Bashful Goose Snack Company, is perhaps the perfect spokes-animal for a world gone mad. And while it’s perhaps easy to be silly as a goose, Hallman’s story transcends the merely silly and arrives somewhere emotionally true.

Hilary Leichter: One of the things I found most impressive about your novel was that nothing felt off-limits. By which I mean, there was a thrilling sense that anything could happen at any time, a sort of zany believability that encompassed all manner of antic magic and pathos and realism. In one moment, the reader experiences a kind of straightforward humor about bureaucracy, and in the next, we are listening to the tale of a talking turtle, as told by the turtle. A quote from an early chapter summed it up for me: “All was normal, but all was not normal.” How were you able to create a world large enough to account for these different timbres and modes of storytelling?

The best thing about this particular time in China, in my opinion, is the almost palpable sense that anything could happen at any moment, that truly anything is possible.

Carly Hallman: I wish I could take credit for building the book’s world, but I have to fess up: reality kindly offered me heaps of help. The best thing about this particular time in China, in my opinion, is the almost palpable sense that anything could happen at any moment, that truly anything is possible. So while my version of China is certainly an absurd one, I would assert that it’s often not that much more absurd than the real version. A good portion of the novel’s story lines and characters are rooted in news stories I’ve read, people I’ve known, experiences I’ve had. For instance, a true-life story about a teenager who sold his kidney to pay for an iPad led me to create a character who made his fortune selling his own hair, and eventually, the hair of others. When, a few months later, a multi-millionaire regaled me with tales of seeing UFOs in her youth, I knew my hair tycoon would also see these UFOs, and would interpret them as meaning he was chosen by supernatural entities to be wealthy and powerful. So a lot of what I did in this book was grab hold of something true and take it one step, or sometimes ten steps, further.

HL: There are some great passages brimming with excess in Year of the Goose. Gluttony, five-star hotel sashimi buffets, secret snack drawers, star-studded galas complete with celebrities and stunt-filled entrances. And at the same time, the characters are obsessed with deprivation. Kelly Hui longs to be a spokeswoman for weight-loss. Wang Xilai becomes an organic hair farmer, nurturing the locks of his employees, or “Heads” as he calls them, and selling their harvested hair to eager actresses and models and celebrities. Was this juxtaposition of deprivation and excess important to you, and to the story you wanted to tell?

In an age of abundance, how do we reconcile our wants with our needs?

CH: Absolutely. I think the juxtaposition of deprivation and excess is one of the most pervasive themes of our time. In an age of abundance, how do we reconcile our wants with our needs? How do we sustain moderation with so many outside forces attempting to sabotage us? Perhaps the easiest way to talk about this is to talk about the food and diet/weight loss industries. We’ve got commercials for Weight Watchers wedged in between commercials for sugary breakfast cereals and bacon double cheeseburgers. I can walk to the corner store here in Beijing and pick up both a box of laxative weight-loss teabags and my choice of twenty different kinds of processed snacks. It’s this brutal game of tug-of-war that advertisers play with us, and, by extension, that we play with ourselves. It’s all very scary and confusing. Lucky for me, I like exploring scary and confusing things.

HL: The book’s form is varied and constantly transforming. It is chock full of diary entries and blog-posts, and is often broken down into short, titled sections that interrupt and overlap. It reminded me very much of watching television and channel surfing, or falling down an internet click hole. Did you set out to create a structure that mimics or mirrors the experience of modern, daily life?

CH: Yes. Growing up as a bit of a misfit, I spent ample time indoors reading, but just as much time watching TV and surfing the internet. As a result, I now enjoy narratives that play with other forms, that remove themselves somewhat from the conventions of what is considered “literature.” I’m a sucker for books that allow the reader to piece together the story from bits of “evidence.” Life of Pi and World War Z are pretty famous, and mainstream, examples of what I mean.

The way I approached Year of the Goose was, indeed, also largely influenced by internet clickholes, and more specifically, how I (and many people) now access news and information. Say, god forbid, there’s some catastrophic event somewhere in the world. Maybe first I’ll read a reference to its occurrence on Twitter. Then, I’ll log onto to a news website or app like the BBC and read an article. Then maybe I’ll go back to Twitter and see what else people are saying. Then I’ll turn on the TV, watch and listen to what CNN has to add. Meanwhile, I’m logging onto Facebook scrolling through commentary from “friends.” On and on it goes. Coming to a story this way makes me feel like I’m a part of it, like I’m a badass sleuth trying to get to the bottom of things. I’m definitely not, but I do enjoy the feeling!

HL: Year of the Goose has multiple (and multiple and multiple) narrators, and you accomplish this really cool feat that I started referring to as Narrator Inception, where each narration contains other voices that co-opt and divert and shift the direction of the story. For example, we start with a new narrator, and then suddenly, he is telling us the story of his grandmother, and the grandmother is telling us the story of a Village Witch, and we’ve been thrown down into a beautiful well of voices. When you finally pull the reader back up to the surface, it’s as if a small miracle of point-of-view has occurred. In question form: how the heck did you do that? How did you keep your footing in one voice, while guiding the reader through entire cast of characters?

CH: Wow, “Narrator Inception” is such a cool way of putting it! I wish I’d thought of it! I also wish I was smart enough and had words enough to explain, technically, how I tackled this, but unfortunately, it was more of a hippy-dippy “feeling” thing, and not so much a cognitive, step-by-step thing. As I wrote these sections, I visualized Russian nesting dolls, and I also tried to tap into the idea that there are many voices living within us that are not our own voice, but are bent and shaped by our own voice. That what we think of as our own personal narratives are partially comprised of chunks borrowed from other people’s narratives.

A small illustration: a friend once told me this story about a near airplane crash she was in. It was a horrific tale. The plane flipped upside down, passengers not wearing seat belts fell from their seats, there were injuries, there was blood everywhere. When the plane was safely upright again, a Turkish pilot with gold teeth burst from the cockpit and excitedly congratulated himself on not actually crashing the plane while all the (conscious) passengers shouted at him to get back in there and drive the damn thing.

Even though the experience wasn’t my own, it has become my story too; I recall it every time I board (or even think about boarding) a flight. And when I recount the story, in my own head or aloud to other people, my friend’s words and phrases and sometimes even her voice do seep through, although my own psychology and experiences and linguistic patterns have hijacked large parts.

HL: I loved the way you sampled different kinds of language throughout the book. Credos, mantras from self-help books, gossip-rag clippings, television jingles. How do these different modes of writing inform your sentence-craft? Where else do you look for inspiration?

CH: I’ve always been a very indiscriminate reader. I enjoy reading things that other, more sensible people might dismiss outright. Catalogs, religious tracts, brochures, self-published self-help books, those pamphlets at doctors offices about diseases, small-time/local magazines and newsletters, vapid gossip magazines, internet bulletin boards and comments sections. Reading these materials reminds me of shopping at flea markets or garage sales. If you have the patience to sift through the verbal garbage, you’ll usually be rewarded by some wonderfully odd turns of phrase and bizarre stories. When I was last in England visiting my fiancé’s family, I read through a quarterly village publication and came across a column by a local man who detailed his lifelong obsession with tree girths. You’re not going to happen upon a gem like that in The New Yorker, you know?

Bad or cheesy advertising language (“Don’t delay! Call Today!”) also really appeals to me, especially stuff from the 80s and 90s. Comedy duo Tim and Eric have done some great parodies of such television commercials and informercials that I find really smart and funny. I’m a huge fan of commercial jingles too; they have this unbelievable staying power. I couldn’t tell you my own phone number off the top of my head, but I can instantly recall and sing for you the Stanley Steamers Carpet Cleaners song.

HL: Speaking of jingles, my favorite one in the book was:”Bashful Goose snacks, eat ’em right up, they’re so delicious, they’ll make you fall in love!” And this, coupled with a line that appears later in the novel: “none of these snacks will ever fill you up.” Could you talk a little bit about the idea of being full? Emotionally, physically, spiritually, artistically? I found it to be a really important theme running through the narrative.

CH: Loads of people, including myself, equate fullness with happiness or contentedness. It’s no wonder then that companies and people and religions and advertisers and etc. have repackaged happiness and fullness, both of which are mere feelings, as “achievable and lasting states.” It freaks me out that even though I’m well aware that there’s no such thing as unwavering, lifelong satisfaction, I still regularly fall into these traps. I’ll catch myself having embarrassing trains of thought like, “If I just bought this amazing new laptop, I’d be more productive and I’d write a best-selling book and an Oscar-winning screenplay and I’d get rich and be forever satisfied.” Or, “If I ordered these special lycra pants, I’d actually start attending yoga class, where I’d make new friends and get in fantastic shape, and then I’d have this amazing new life.”

As humans (and as consumers) we’re kind of obligated to keep trying, to keep buying, even if in the long-term, failure is inevitable.

So the gist of what I want to say about fullness and happiness is that they’re not temporary states. They’re fleeting. To chase them is to engage in an endless, but not entirely trivial, pursuit. I mean, we still have to eat, right? We still have to seek moments of pleasure, of joy. As humans (and as consumers) we’re kind of obligated to keep trying, to keep buying, even if in the long-term, failure is inevitable.

HL: Many of the locations in the book are sites of seclusion. We visit a camp for obese children, a monastery, and a hidden village for ex-millionaires. I half expected to see a writing residency pop up! Is there something magical for you about isolation in fiction, the sequestering of a character?

CH: It’s funny you point this out — this actually wasn’t a conscious decision at all! In hindsight, I think this motif probably emerged from two places. The first is I’m an introvert and I spend a significant amount of time alone, or in small groups of people. So the settings mirror my preferred reality. The second is that I believe people are often at their most raw and interesting when they are alone, when they think no one’s watching. A better writer might tell you to throw your characters out into the world, to let them interact with as many other characters and settings and circumstances as possible. You should probably listen to them. But for me, it’s fun (and admittedly a wee bit messed-up) to drop a character into a secluded or closed-off site and then play voyeur.

HL: What’s next? Are you working on any new projects?

CH: I’ll be in the U.S. in January for a small book tour, which I’m both excited and nervous about. My memoir-in-essays about growing up in a small Texas town, A Farewell To Walmart, is scheduled to be published early 2016 through Kindle Singles. And I’m also working away, slowly but surely, on novel #2.