Lit Mags

The Other Time a Grown Man Threatened My Life

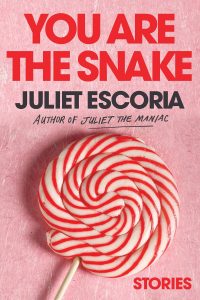

An excerpt from YOU ARE THE SNAKE by Juliet Escoria, recommended by Ashleigh Bryant Phillips

Introduction by Ashleigh Bryant Phillips

Juliet Escoria has built her career writing semi-autobiographical accounts of unlikeable, edgy women—party girls who struggle with addiction and mental health. Her characters are often described as subverting expectations, but I’ve always felt this was a quick and lazy take, especially (and unfortunately) cliché for American women short story writers working in a form epistemologically defined by male masters. Escoria’s writing, her women, have never wanted our pity. In You Are the Snake, her second short story collection, Escoria confronts us. Sylvia Plath wrote, “there is a charge for the eyeing of my scars.” The women in You Are the Snake don’t want applause for what they’re capable of, despite their sex. Every story is a power play, fucking with us and the form.

In “The Other Time a Grown Man Threatened My Life,” our unnamed narrator is college-aged but not in college. She works at a bookstore. One “lame night” just like all the rest, she’s partying with her friends in a vacant lot across from a shopping center. The new guy, who works security, asks her for a cigarette. Then he asks her for a light. “He tried to do the thing that creepy guys always do, making you light their cigarette, or the reverse, so there was no choice but to be close to their body.” The narrator gives him her lighter, tells him to keep it, and then immediately goes off to find her best friend, hugging her like she hasn’t seen her all night.

In “The Other Time a Grown Man Threatened My Life,” our unnamed narrator is college-aged but not in college. She works at a bookstore. One “lame night” just like all the rest, she’s partying with her friends in a vacant lot across from a shopping center. The new guy, who works security, asks her for a cigarette. Then he asks her for a light. “He tried to do the thing that creepy guys always do, making you light their cigarette, or the reverse, so there was no choice but to be close to their body.” The narrator gives him her lighter, tells him to keep it, and then immediately goes off to find her best friend, hugging her like she hasn’t seen her all night.

There are other power plays in You Are the Snake: a girl smacks her new stepmother in the face, a woman slips out of the house and gussies up at the bar while the rest of her family is sleeping, and a nun still remembers stealing back an eraser that was stolen from her as a child. I expect people will describe these stories as women misbehaving, but these women deserve more. This is a collection from a writer following her instincts: exploring isolation, loneliness, the beauty of violence, and the gifts of love—all while writing with vulnerability.

Later in “The Other Time a Grown Man Threatened My Life,” the narrator is driving home from another party when she sees something in the middle of the road. “I noticed it just in time. It was a boulder, a big chunk of sandstone from the cliffs above.” She gets out and pushes the boulder into the other lane. I can’t stop thinking about it: this young woman pushing an annoying huge rock out of her way, wiping the sand on her jeans, and going on like it was nothing.

I keep returning to the cigarette-lighter exchange—and to the moving of the boulder. Each time, we find a young woman in a no-choice situation, quietly gaining control.

– Ashleigh Bryant Phillips

Author of Sleepovers

The Other Time a Grown Man Threatened My Life

Juliet Escoria

Share article

An excerpt from YOU ARE THE SNAKE by Juliet Escoria

There was this weird hippie guy who hung around the Palms. He owned a van and a llama and not much else. We called him Van Man. I didn’t know the name of the llama. The two of them slept in the van every night at the far end of the parking lot, Van Man in the driver’s seat, llama in the back. He’d cut out panels in the van so the llama could stick its head out. It didn’t seem like a very comfortable living arrangement, but what did I know?

One day I was working the cash register at the bookstore when Van Man came into the store with the llama. He walked right over to the magazines, the lead for the llama wrapped loosely around his fingers like he was holding a balloon. It was dead silent for a second, a thick communal shock, everyone staring at the man and his llama. The moment passed, and everyone began talking over one another at once. A fucking llama. In a fucking bookstore.

I really liked my manager, this nice guy with a trendy beard who’d gotten me into Bret Easton Ellis, but when he told Van Man to get out of the bookstore, he seemed like nothing more than a spineless little bitch. “Come on,” my manager said. “Let’s be cool. Take the llama out of the store.”

“There’s not a sign,” Van Man said. And it was true. There wasn’t. There was a sign that said no dogs but it mentioned nothing about cats or rabbits or llamas. But there wasn’t a sign about how you weren’t allowed to bomb the store or light the books on fire or jerk off in the erotica section (which had happened before) either.

My manager left to call security. Everyone was just standing around, staring, as Van Man paged through the new issue of Maxim. A few minutes later, the security guard showed up. He was a pathetic man, pink and doughy. My friends and I all worked in the shopping center—the bagel store, the Meineke, the sandwich shop—and when we got off work, we met up at the tables in front of the movie theater to talk and smoke, waste time until there was something better to do, somebody’s parents out of town, a bonfire at the beach. We knew all the security guards. We called this one Tweety because of his car, a yellow RAV4 with a Tweety Bird sticker on the window and a Tweety Bird tire cover and a personalized TWTYBRD license plate. It was impossible to take him seriously ever—not when he yelled at us for drinking or smoking or making too much noise. The worst he could do was order us off the property. When that happened, we walked across the drop-off area to do the same things we did at the tables but in front of the stop sign instead.

“You gotta go,” he told Van Man.

“Whatever, man,” Van Man said, like some stoned guy in some stoner movie. “I’m just reading a magazeeeeeeeen.”

“You gotta get the llama out of here,” Tweety told him, and pulled on his arm, the one that wasn’t holding the llama lead.

That pissed Van Man off. He started flailing his arms, which yanked on the llama lead, which made the llama let out a long weird snort like a horse. But finally he relented, petted the llama on the nose to settle it down, allowed himself to be escorted out of the store. They were at the door when Tweety told him, “And don’t you come back,” trying too hard to play a role.

Van Man laughed, like he had the exact same thought as me. “Hope this makes you feel real big, mister badgey-badgey five-dollars-an-hour man,” he said. “Mister badgey five-dollar fake pig.”

I couldn’t help it. I started laughing. I tried to stop, ring up the customer, a middle-aged woman buying a Dean Koontz novel. She seemed shook-up, clutching the shitty book. I couldn’t. “Sorry,” I told her, beeping the book under the scanner. I was still laughing when I gave her the change.

When I got off work, I went right up to the circle, sat down in one of the metal chairs, told the guys who were sitting there all about it. Mister badgey-badgey five-dollars-an-hour man. And from then on, that’s what we said to Tweety whenever he told us to be quiet or settle down or put away that beer.

The security guards all came and went, working at the Palms for a couple months or a year before disappearing, nearly indistinguishable from one another. Useless doughy guys with buzz cuts, weak rejects from the actual police, who rode around the shopping center in a golf cart because they were too fat and lazy to walk. Tweety had only stood out because of his car.

But one day, there was a new security guard at the Palms, different than all the rest. He was giant, nearly seven feet tall, and gorgeous in a scary way, cheekbones and angles, a shaved head that was almost sculptural. The first time I saw him I felt scared in a way I couldn’t explain. I’d just gotten off work when he walked around the corner. The security guards had these sticklike things they held up to various receivers around the shopping center until they beeped, I guess to ensure they were doing their rounds. He came around the corner, big and muscular and scowling, beeping his wand. His hair was so short you could see the perfect shape of his skull.

I still felt as though the security guard had something to do with it, had been one of the final straws that damned Van Man to his death.

Later that day, Colin, who was always around, Chandra, my best friend, and I were smoking a joint in the corridor behind the movie theater when we heard someone yelling. I stood up, looking over the low stucco wall we were crouching behind. I saw Van Man getting yelled at by the new security guard. “You get the fuck off this property,” the security guard was saying. Van Man was standing outside his van, next to the llama’s head peeking out. I waited for him to say something but he didn’t. Instead, Van Man walked around the van, opened the door, got in the driver’s seat. I heard the van turn on, put-put-put. I watched him drive out of the parking lot, around the hill, until he drove out of sight. The new security guard continued his rounds, walking. I never once saw him in the golf cart.

The new security guard ignored us for a long time, didn’t say a word as we sat at the circle and smoked. One day, though, it was the release of the latest installment of a movie franchise, and the space in front of the theater, our space, was packed. Someone had a big bottle of store-brand vodka, and we were passing it around, pouring it into soda cups. We were about to head out to one of the dirt lots that had appeared by the side of the new freeway, waiting to be turned into another subdivision, one of our go-tos when there was nowhere else to party.

We didn’t notice him at first. One minute nobody was there, and the next minute there he was, standing behind Colin, confusing because of his size. Colin was holding the bottle, pouring it into his can of Pepsi. The new security guard put his hands on Colin’s chair, one on each side of his neck. Colin was an asshole, didn’t care about respecting anybody, but he froze. The security guard’s eyes were blue and sharp like crystals. His face was completely expressionless. I couldn’t tell if he actually cared or if he was just doing his job. “Put the bottle away,” he said, quiet and calm, but there was something buried underneath his words that chilled me.

I wondered what Colin would do. Normally he’d make fun of the security guard, give him shit. But he just put the cap on the bottle, handed it to somebody, who put it in their backpack.

The security guard took his hands off the chair. As he walked away, I noticed something peeking up over his blue uniform collar. Fine black lines, uneven in color. I didn’t know a whole lot but it looked like a prison tattoo, the tip of an Iron Cross.

I was sitting at the chairs, waiting for Chandra to arrive. There was an old paper sitting on one of the far tables and I didn’t have anything better to do, so I walked over and picked it up, paged through it. A headline caught my eye, buried toward the back of the paper.

Ocean Beach Victim Was Colorful Local Known as the “Llama Man”

The article was about Van Man. The Llama Man was Van Man. He was dead, had been found drowned twenty miles south in OB, weights on his ankles and rocks in his pockets. A suicide note had been left in the sand. He was bipolar, the article said. He’d given away the llama a few days earlier to a guy in the neighboring county with a farm. This was a week ago, shortly after the new security guard told Van Man to leave. I didn’t think he’d been murdered or anything as conspiratorial as that, but I still felt as though the security guard had something to do with it, had been one of the final straws that damned Van Man to his death.

A couple weeks later, it was a Friday but there wasn’t anything to do. It was the weekend after Thanksgiving, and a lot of people were busy or out of town so there was a smaller group than usual, maybe fifteen of us, trying to figure out where we could go. Finally we decided on the beach. There were few enough of us that the cops probably wouldn’t come. None of us were old enough to buy alcohol except for Colin. We pooled together money, and there was only enough for a case of beer and a pint of cheap vodka but that was fine. We handed the money to Colin. “I lost my ID,” he said.

“What?” I said.

“Yeah, I lost it.”

“Shit.”

“Don’t worry about it,” he said. Then he disappeared with the money. Maybe he was going to steal it. Maybe he knew someone working at the gas station. But he came back empty-handed.

“What the fuck?”

“Be patient,” Colin said. He had a little smile on his face, the way he did when he’d come up with a good scam. When nobody was looking a few minutes later, he waved at me to follow him. We walked behind the theater to his car, a beat-up maroon IROC-Z with broken windows that wouldn’t roll down. It reeked in that car, from Colin always hotboxing it with cigarettes due to the broken windows. We got in the car and drove around the corner to the alley. I was just about to ask Colin what we were doing when the new security guard walked up. He was carrying a case of Miller Lite and a paper bag. He handed it to Colin, who got out of the car to put it in the trunk. I watched them bump fists in the rearview. “Thanks, Derrick,” Colin said, the first time I heard his name. The security guard, Derrick, said nothing to me, simply looked back at me with a face full of hatred, like he knew I possessed some despicable secret.

This happened a few more times—Derrick buying us beer—until eventually he started partying with us. It was another lame night, nowhere to go, so we just went across the street to Beer Woo, this vacant lot that was supposed to turn into another shopping center but was empty for years instead, due to some boring fight with the city council. It was higher than the shopping center and nobody ever seemed to notice us, which felt a little magical, hiding in the camouflage of plain sight. Derrick had two cases of beer, Miller Lite again, and also a bottle of Jameson. We walked across the street and he didn’t say anything, and I was starting to think he was just straight-up mean. But when we got to Beer Woo, he asked me for a cigarette and I gave him one and then he handed me the bottle of Jameson. I opened it, but I didn’t have anything to drink out of, and I was afraid he’d yell at me if I put my mouth on the bottle. He seemed to notice, some animallike intuition. “Go on,” he said. “Take a sip.”

I took a pull from the bottle. It burned. I handed it back to him, and he took a sip too, his mouth touching the same part of the bottle as mine. I knew there was logically no meaning in that but I still felt violated, knowing a part of myself was now a part of him too, a weird thrill.

He asked me for a light so I pulled out my lighter. He tried to do the thing that creepy guys always do, making you light their cigarette, or the reverse, so there was no choice but to be close to their body. I pretended not to notice, placed the lighter in his hand. “You can keep it,” I said, even though it was the only one I had. I walked away, pretended to just notice Chandra, hugged her like I hadn’t last seen her a few minutes ago.

“What are you doing?” she said.

“He creeps me out,” I said.

“Who? Derrick?”

“Shhh,” I said. “I don’t want him to hear.”

Chandra looked at me, confused. She seemed to think Derrick was fine, no different than the rest of us.

Derrick came out with us a lot after that. I learned that he lived in El Cajon, thirty minutes away and one of the shittiest places to live in San Diego County. In San Diego, everyone said that anywhere that wasn’t the coast was filled with white supremacists—El Cajon, Santee/Klan-tee, Spring Valley, Lakeside. Racists. El Cajon was the shittiest of them all. At least Santee looked like a generic Southern California suburb, with tree-lined streets and the big Costco. El Cajon, on the other hand, was hot, poor, and ugly.

It didn’t matter, though, because Derrick was an actual racist. A skinhead. He listened to horrible music, racist punk and racist death metal. The lines I’d seen on his neck were indeed a prison tattoo, or at least that’s what he said, eighteen months in San Quentin. Of course it was San Quentin. There was another tattoo on his chest, which I saw when he took off his uniform, two lightning bolts like a regular fucking Nazi.

For some unfathomable reason, Chandra didn’t believe me, as though the tattoos and music and shaved head were random aberrations.

I didn’t know if I believed him. He never gave details about what his crimes entailed, wouldn’t tell us why he was sent to prison. But mostly I didn’t believe him because I couldn’t imagine a security guard firm in Santa Bonita hiring a felon.

Nobody seemed to care except me, including Chandra, who was half Mexican. Derrick didn’t seem to notice her eyes or her skin or her last name, Martinez. Chandra didn’t seem to notice either, the bad music or the bad tattoos. The two of them even made out one time. When we talked about it later, she didn’t even care. “What?” she said. “He’s hot.”

“He’s a fucking skinhead,” I said, but for some unfathomable reason, Chandra didn’t believe me, as though the tattoos and music and shaved head were random aberrations.

We were running this scam at Home Depot. One of us would go in, buy a spindle of wire that cost twenty bucks. The scam was that we’d steal one of the barcodes from the fiber optics cables that looked the same but cost five times as much. We’d peel off the original barcode, replace it with the stolen one. Then we’d drive to another Home Depot, return it, and pocket the difference. Home Depot gave you cash on returns, didn’t even want to see an ID. With the money, we bought beer and a room at the Motel 6 off the freeway. Eventually we got greedy, started to return two spindles instead of one, buy cocaine and kegs instead of just beer. The parties at the Motel 6 got so wild that we had to get a new person to rent the room each time because we left them so trashed.

It was late, maybe 4:00 a.m. We’d been doing lines of coke all night at the Motel 6. It brought that weird thing in the air, tense and thick. We ran out of drugs and Derrick didn’t know we were low and he got mad. All of a sudden he was yelling, indecipherable. His eyes were bloodshot and red. I guess a lot of the coke money had been his and he was mad it was gone.

“Dude,” Colin said. “You got to quiet down.”

Usually Colin was the one Derrick liked best, but that just pissed him off. I watched him get up, walk over to the shitty desk, and pick up an empty beer bottle. He stood there for a moment, frozen, before breaking the bottle on the edge of the desk. “You stole it,” he said, walking over to me, the broken bottle over his head.

I sat up from the bed. I had no idea why he was blaming me. I didn’t feel scared, for some reason. He looked so stupid, a big dumb boy, with big-dumb-boy tattoos. The look in his eyes was dull and blank and I was tiny and didn’t know how to fight, but still I felt like I could take him, somehow. I wanted to laugh at him, to tell him he was a stupid boy, but that didn’t exactly seem like the best move. So I just sat there, staring at him, his stupid cold blue eyes, and it felt like everything was both pulsing and frozen.

“Dude,” Colin said. “Everything is chill.”

Derrick turned to him, as though he had forgotten what he was doing. He dropped the broken bottle on the floor. I thought for a second that he’d calmed down. He walked over to the TV. He picked it up. He tried throwing it but it was still plugged into the wall. It yanked out when he threw it, but instead of launching in the air, it tumbled right down onto his feet. The TV broke with a pop. He screamed, high-pitched, like a little girl.

None of us knew what to do. When it came down to it, we were just nice suburban teens. We didn’t break TVs. Something seemed to shake loose from Derrick in that moment, all of us standing there, silent and horrified. He started laughing. “Shit,” he said. “I went a little crazy.”

Chandra and I left the hotel room after that. I wasn’t sober enough to drive but I had to get out of there. We took the coast home, thinking I’d be less likely to get pulled over that way.

We were up on the hill, right before the stoplight closest to my neighborhood, when I saw something in the middle of the road. I noticed it just in time. It was a boulder, a big chunk of sandstone from the cliffs above. We got out of the car. The night was dead silent and there was a bit of fog rolling in from the coast, everything washed out in the yellow of the streetlight.

Chandra and I were able to move it, just barely, out into the other lane. The sandstone got all over my hands, stained my jeans.

After the TV incident, we tried to stay away from Derrick, no longer invited him out, but sometimes he went up to the circle when he got off work anyway, came out with us uninvited. I did my best to ignore him, stay out of his way. I think he noticed. He was always staring at me, like everything was all my fault.

It was morning, way too bright, but I was sitting at the Palms anyway. It had been a long night and I was still too jacked up to go home. My mom was always threatening to drug test me, and if I failed the drug test, she’d kick me out, so I was staying away from home more and more. After checkout time at Motel 6, I had Colin drop me off here, until I could sober up and walk home.

I’d been sitting there for a few minutes, elbows on my lap, head hanging down, trying to get my bearings though it was hard in the hot sun, when I heard someone yelling. It sounded like a mess of nonsense except for two distinct words: fucking bitch.

I looked up, feeling dazed. The light was splotchy. I saw Derrick, maybe fifty feet away, walking toward me. He had a cup from Subway in his hand, was dressed in jeans, his security guard shirt on but unbuttoned. He started screaming at me. I had no idea why. I’d done nothing to him. He was calling me a bitch and a cunt, a stupid bitch, a dumb fucking cunt. He stayed across the pavilion though, away from me, which was confusing, like he was afraid of me. I didn’t say anything to him because it seemed so insane. I was just sitting there, hungover and tired.

Me not saying anything seemed to piss him off more. He started saying he was going to kill me. “I’ll murder you, bitch. I’ll bury your body in a shallow grave. You’ll rot, bitch.” He threw the soda cup at me but missed. I watched the ice splatter on the cement.

I didn’t know what to do. It all seemed so wildly illogical. I couldn’t help but imagine my decaying body, bugs eating my eyeballs.

I grabbed my purse without looking at him. I walked down to the bookstore, went into the break room, used the phone. I asked my mom to pick me up, waiting for her in the safety of the bookstore, looking out the window the whole time, just in case. When I got in the car, she said nothing about the way I smelled or the way I was acting.

We never saw Derrick again. All I know is he got fired. I don’t know why. I didn’t tell on him. That wasn’t how my friends treated it, though. They acted like I did it, like I’d conquered him, like I’d done something, anything, like I’d won.