interviews

Tiphanie Yanique on Gabriel García Márquez’s Love in the Time of Cholera

Colin Winnette admires the writer Tiphanie Yanique, so he asked her to suggest a book. She suggested Love in the Time of Cholera by Gabriel García Márquez. Colin read it, then they talked about it.

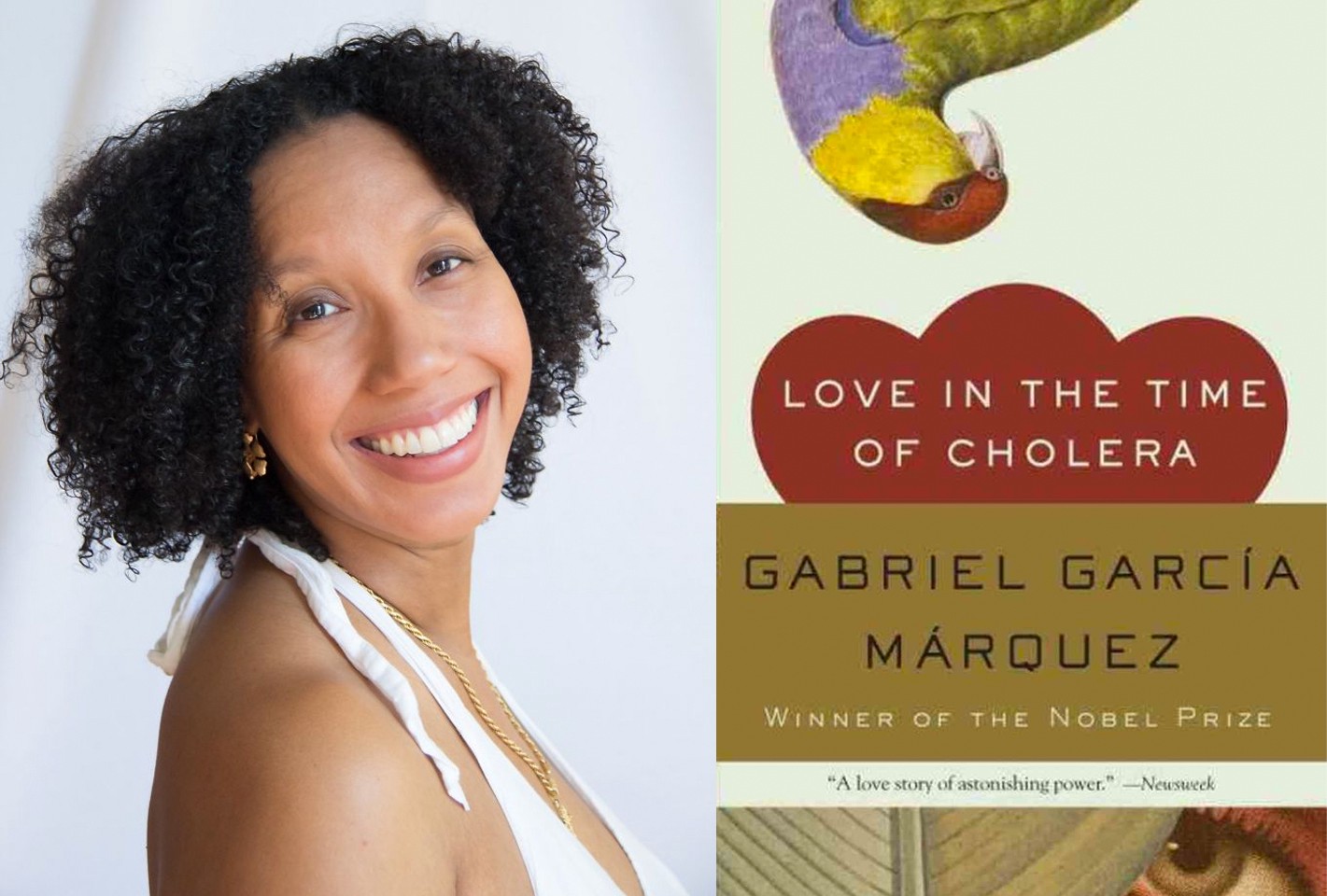

Tiphanie Yanique is the author of the short story collection, How to Escape from a Leper Colony (Graywolf Press in 2010), the picture book I Am the Virgin Islands (Little Bell Caribbean in 2012), and the novel Land of Love and Drowning, (Riverhead/Penguin 2014). She has been listed by the Boston Globe as one of the sixteen cultural figures to watch out for and by the National Book Foundation as one of the 5 Under 35. Her writing has been published in Best African American Fiction, The Wall Street Journal, American Short Fiction and other places.

She is now an assistant professor in the MFA and Riggio Honors programs at the New School in New York City. She lives with her husband, son and daughter. They split their time between Brooklyn and St. Thomas.

Colin Winnette: When did you first read this book? Do you remember the exact circumstances that led to your picking it up?

Tiphanie Yanique: I remember hearing about the work of Gabriel García Márquez. I cannot remember ever reading this Love in the Time of Cholera in a particular class…but I know I discovered his work sometime in undergrad. I first read 100 Years of Solitude. I had the sense, while reading that, that I was engaging with something large and shattering. The kind of literature that knows it is attempting to address big things like nationhood and family. But I didn’t know shit about those things, so I read it mostly feeling these things going over my head. But I knew I WANTED to grasp these things. So I turned to Love in the Time of Cholera. It had the word love in it and this was something I’d been thinking very deeply about for a long time. I’d grown up on the love story of how my grandparents met. I’d already had a profound romantic love in my own life. So it seemed like a good entry point to this master’s work. Of course, it wasn’t that simple. This was also a novel about nationhood and family…but the entry point was romantic love.

CW: How did your grandparents meet?

TY: They met at a party. They danced to the Irving Berlin song, “They Say It’s Wonderful.” They were in love by the end of the night. These are the only facts they both admit to!

CW: When I first read this book, it struck me as incredibly romantic. This time around, I started to think it was…pragmatic, in a lot of ways.

TY: Oh, it’s both for sure. Both Fermina and Florentino are young when they first fall in love. They are trapped by circumstance. Their love is a rebellion. Their love defines them. Their love thrusts them into adulthood. Florentino stays there. He continues to create himself with Fermina’s gaze in mind. But Fermina, as a woman of her time and social status, has a sudden realization that she must be less rash in her choice of a life mate. Her adulthood means making a more deliberate choice. She chooses against passion, but in doing this she doesn’t choose against herself. It’s a different way to choose herself. And she doesn’t regret this choice…not for many years anyway. It does seem, though, that if we choose against romance, against passion and for stability, for safety, that we might sometimes end up happier, more successful…but that eventually we will have deep regret. We always want true love. Eventually, that’s what we want. Because, of course, it’s always what we want. Even if it’s the wrong choice.

CW: That’s a great way to put it, it was “a different way to choose herself.” So what is the foundation of her regret? There is love between Fermina and Dr. Urbino — a kind of love that I, if I’m being honest, found very moving in certain moments. So if she feels regret, longing for “true love,” how would you define or describe what true love means in the book? What sets these two relationships apart?

TY: The love between Fermina and Dr. Juvenal Urbino is no less true than the love between Fermina and Florentino. In fact, it might be more true. After all, Fermina and Juvenal raise a family together, share a household…mold their lives to fit the demands of their marriage. Many forms of love can’t sustain all that work. But there is no emotional beginning to Fermina and Dr. Urbino’s love. It grows from her practicality, not from her passion. A passionate love can mature to develop it’s own practical aspects, but it does seem much harder to kindle a passion that never arose organically to begin with. That doesn’t make one more true than the other, but it does seem to me that a love that begins with romance and intensity has a greater potential to be a fuller love, and therefore perhaps more fulfilling.

CW: GGM’s trademark “magical realism” is very tamed, very isolated and controlled in LITTOC. In my reading, the fantastic elements don’t alter the course of the story much, though they add texture and style to its telling. Is this a fable? An alternate world? A magical realm? Or does the book feel grounded in our everyday world. Your book felt much more fantastic and imaginative than this particular Marquez. And that’s not a dig at Marquez, I’m just saying this book has a fairly narrow focus, in some ways, or a smaller aperture than some of his other novels.

TY: How fascinating. I’ve never read Love in the Time of Cholera with the understanding that you’ve illuminated. I suppose this is because I see the love of Fermina and Florentino to be intensely magical. It is the main magical real element in the book. It’s incredibly pervasive, impacting the entire life of one character in even the most minute ways. I suppose I think this because of the way I think of magical realism, which is that it’s real. It’s life as we know it — you, too. Writers who choose to highlight the magical real, versus, say the psychological or social real, are just accessing a different level of human being and human interaction. The only way I can believe in a love that lasts a lifetime is via the lens of magical realism. That shit just does not make sense psychologically or socially.

CW: The story in LITTOC is an interesting blend of loose, unpredictable, and tidy. On a sentence level, there’s no telling where we’ll go next. But on a larger, narrative scale, we know exactly where the story is headed. I got the impression that he started with an ending in mind but let himself go wherever he felt like going as he worked his way toward it.

TY: Garcia Marquez was writing the story of how his parents met and married…so he says anyway. Of course, he adds his own embellishments, as any fiction writer would do. My guess is that he took what he knew of the story and then wrote it as beautifully as he could. I bet he hunted down the beauty…let it take him away and back towards the “”true” story. That beauty allows, perhaps even requires, a meandering journey.

CW: Oh, I had no idea. How interesting. I’m guessing Florentino and Fermina are standing in for his parents? Both relationships have their admirable qualities and their downsides. The “practical” side vs. the crazy in love side. The book makes a case for both, though it does seem ultimately to side with crazy in love.

TY: Yeah, well, Gabo always seemed to suggest that his parents were crazy in love. They made huge sacrifices to be with each other and to stay with each other. That didn’t stop his father from having children outside the marriage who his mom often took in as her own — so, not practical. Nope.

CW: Your new novel, Land of Love and Drowning, invites comparisons to LITTOC, and Marquez’s work in general. Did you think about your work in relation to Marquez’s when you were writing?

TY:I always think about Gabo. He’s the paternal deity that rules my writerly head. My title, in its subject and even it’s grammatical structure, is a tip to him. My novel also has a long “introduction” where characters who are historical to the rest of the novel take center stage and then disappear. LITTOC gave me permission to do this. Besides, structural elements however, there’s not much I’ve intentionally culled from LITTOC. Most of the magic in Land of Love and Drowning is intensely organic to the space I am writing about. The cowfoot woman, obeah women, the Anancy…these beings walk around the Virgin Islands. Eat in our restaurants. Sure, tourists don’t see them. And even people who have lived in in the VI for a few years might completely miss them. Islands keep their secrets. In some ways, because of Americanization and because of tourism, the Virgin Islands has done a fantastic job of hiding our more mysterious elements. It’s getting to the point now that we’re even hiding them from ourselves. I’m hoping literature might be a good place to put those mysteries…a place where we can remember them, but also still keep them close if needed.

CW: Do you have any personal stories like young Jacob’s?

TY: Oh, of course! But like I said…some secrets must be kept. So often these magical stories in our personal histories implicate someone we love…as Jacob’s story does. My family is relieved that I’m a fiction writer, not an essayist.

CW: That idea of “permission” is important, I think. Great books often offer a sense of freedom, I think. As a writer reading, I’m always waiting for that moment when the doors in my head start to open and all the blinds lift. What else did you learn from this book?

TY: One of the things this book teaches is that romantic love is still an important things to talk about in stories. Not just because it makes us feel warm and fuzzy, but because it’s IMPORTANT. It’s political, it’s social, it’s personal. But also it’s love. Come on. Nothing is more important.

CW: It’s also very difficult to write about. Or write about well, because on the other hand, it’s a very easy tool to use, narratively. (Why did she do it? Because she loved him/her.) In your opinion, what other books get it right?

TY: All the big things are hard to write about. Death, sex, war, love. They’re so achingly familiar — how to make them particular? How to make them reveal something about the human condition that they haven’t revealed in literature before? There’s a great book of literary criticism called The End of the Novel of Love. It’s by Vivian Gornick. She does a quick and sharp job of explaining why “she did it because she loved him” doesn’t much work in literature anymore. I’m with her. Writing about love these days is hard, hard work…but love, even romantic love, still remains vital to all the questions of why and how. So we’ve still got to write about it. I can think of quite a few books that are still trying to be about love. The Feast of Love by Charles Baxter, Jazz by Toni Morrison, All I Love and Know by Judith Frank, and Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout come most urgently to my mind.

CW: Would you share a passage from the book, or a few sentences, something that you think is either representative or just exceptional on its own?

TY: Oh this is easy. Garcia Marquez’s opening lines are simply undeniable:

It was inevitable: the scent of bitter almost always reminded him of the fate of unrequited love. Dr. Juvenal Urbino noticed it as soon as he entered the still darkened house where he had hurried on an urgent call to attend a case that for him had lost all urgency many years before. The Antillean refugee Jeremiah de Saint-Armour, disabled war veteran, photographer of children, and his most sympathetic opponent in chess, had escape the torments of memory with the aromatic fumes of gold cyanide.