interviews

Ursula K. Le Guin talks to Michael Cunningham about genres, gender, and broadening fiction

To celebrate this fantastic conversation between Hugo-and-Nebula award winner Ursula K. Le Guin and Pulitzer Prize winner Michael Cunningham about writing, freedom, and defying the limitations of genre, Diversion Books are offering Electric Literature readers the eBook of LeGuin’s genre-busting novel The Lathe of Heaven for just $3.99:

“The Lathe of Heaven” by Ursula K. Le Guin on Ganxy

Michael Cunningham: Writers are always, pretty much by definition, writing within a historical period, though that period may not acquire a name until later. I don’t believe the Victorians thought of themselves as the Victorians. OK, the Modernists thought of themselves as Modernists, but still…

I wonder sometimes what period we’re in, in 2014. I personally don’t find “post-modernism” very satisfying.

Although I don’t have a name for it — I’ll trust history to provide that — I feel like the most prominent aspect of this period is what I suppose I’ll call “broadening.”

Broadening in the sense of a much larger collective conviction about who’s entitled to tell stories, what stories are worth telling, and who among the storytellers gets taken seriously.

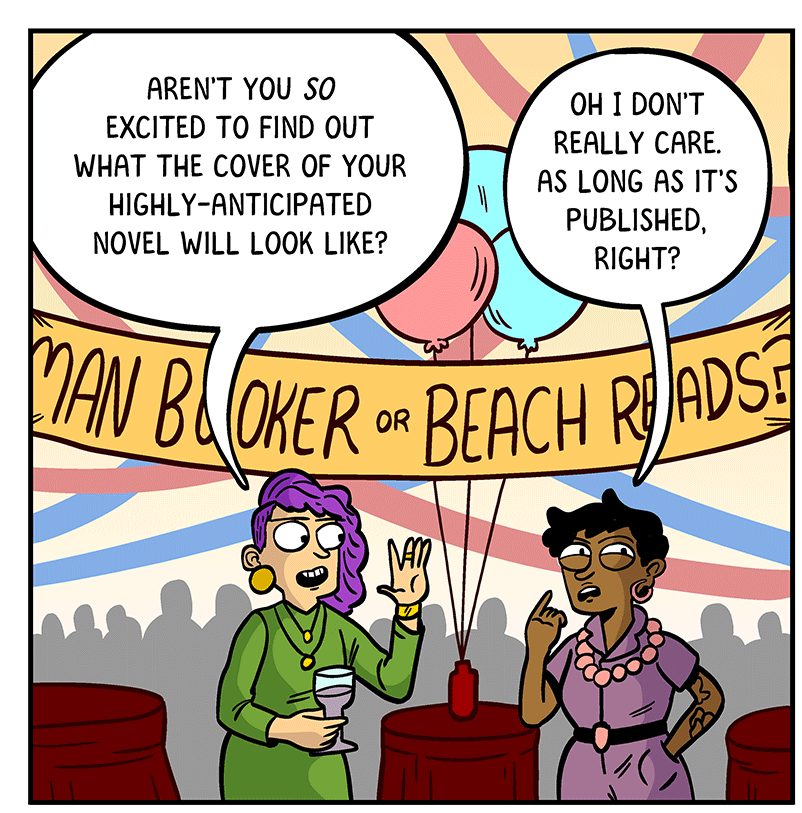

I think of “broadening” not only in terms of race and gender, but in terms of what has long been labeled “genre” fiction.

I believe that some of the most innovative, deep, and beautiful fiction being written today is shelved in bookstores in the Science Fiction section.

I believe that some of the most innovative, deep, and beautiful fiction being written today is shelved in bookstores in the Science Fiction section. That that section probably contains more fascinating books than does the… what to call it?… mainstream fiction section…

Could you talk about that? About the breaking-down of the barriers between “genre” books and the books that are generally piled on the front tables at Barnes & Noble? This is especially important to me, in that I’m always trying to talk readers into venturing into genre fiction, and still encounter a surprising degree of resistance. The line, “I don’t read science fiction” emanates from a surprising number of well-educated, erudite mouths.

Ursula K. Le Guin: Well, you’ve said much of what I’d have said, and I’m delighted to hear it said by a writer whose fame is not within a “genre” but in what is still called literary fiction.

And that, of course, is the lingering problem: The maintenance of an arbitrary division between “literature” and “genre,” the refusal to admit that every piece of fiction belongs to a genre, or several of genres.

There are very real differences between science fiction and realistic fiction, between horror and fantasy, between romance and mystery. Differences in writing them, in reading them, in criticizing them. Vive les différences! They’re what gives each genre its singular flavor and savor, its particular interest for the reader — and the writer.

But when the characteristics of a genre are controlled, systematized, and insisted upon by publishers, or editors, or critics, they become limitations rather than possibilities. Salability, repeatability, expectability replace quality. A literary form degenerates into a formula. Hack writers get into the baloney factory production line, Hollywood devours and regurgitates the baloney, and the genre soon is judged by its lowest common denominator…. And we have the situation as it was from the 1940’s to the turn of the century: “genre” used not as a useful descriptor, but as a negative judgment, a dismissal.

“The genres” were ignored altogether and realistic fiction alone was left as literature, in the minds of the men who controlled criticism and teaching. Realism is of course a tremendous and wonderfully capacious literary genre, and it has dominated fiction since 1800 or before. But dominance isn’t the same thing as superiority. Fantasy is at least as immense as realism and much older — essentially coeval with literature itself. Yet fantasy was relegated for fifty years or sixty years to the nursery.

I love to remember Edmund Wilson, king of the realist bigots, squealing “Ooh those awful Orcs!” and believing he’d made a witty and cogent critical point

These days, I love to remember Edmund Wilson, king of the realist bigots, squealing “Ooh those awful Orcs!” and believing he’d made a witty and cogent critical point.

As you see, I bear some resentment and some scars from the years of anti-genre bigotry. My own fiction, which moves freely around among realism, magical realism, science fiction, fantasy of various kinds, historical fiction, young adult fiction, parable, and other subgenres, to the point where much of it is ungenrifiable, all got shoved into the Sci Fi wastebasket or labeled as kiddilit — subliterature.

And the labels stick. As you say, a lot of people still maintain genre prejudice. I still meet matrons who tell me kindly that their children enjoyed my books but of course they never read them, and people who make sure I know they don’t read that space-ship stuff. No, no, they read Literature — realism. Like The Help, or Fifty Shades of Grey.

But the walls I hammered at so long are down. They’re rubble. I like your term, “broadening,” for what’s going on. I agree that “postmodern” is a truly flabby word. But I guess I don’t really want a label for the new place we’re in. Labels turn into cages. I love to see people like Michael Chabon and Kij Johnson and David Mitchell and Jo Walton — and above all, old José Saramago! — waltzing around the literary landscape, freely using fragments of genres to build up their beautiful stories, finding unclassifiable forms for irresistible narratives. And to see the literary reputation of great nonrealists like Jorge Luis Borges and Italo Calvino holding steady or rising — along with the status of the Author of the Awful Orcs, and some obscure writers of that space-ship stuff, such as my Berkeley High School classmate, Philip K. Dick. Vive la Révolution!

MC: It’s been written of Samuel R. Delany’s work that, “By imagining a new gender and resultant sexual orientation, the story allows readers to reflect on the real world while maintaining an estranging distance.”

The story in question was, “Aye, and Gomorrah,” but it could be said of other work by Delany, and certainly of some of your own work, very much including The Left Hand of Darkness.

You needn’t focus specifically on the advantages of claiming the right, in fiction, to re-imagine genders, though that would of course be interesting. You could also talk a bit, if you like, about other freedoms offered when a writer releases herself/himself from what I suppose I’ll call the “natural” world — that is, from the planet Earth, its denizens and conventions.

UKLG: I think Delaney was using Darko Suvin’s very useful concept of “cognitive estrangement” for what is perhaps the characteristic gesture of science fiction: Giving the reader a new place from which to look at the old world. Or, as Suvin said, a mirror in which you can see the back of your own head. Stendhal, that dour realist, boasted that his novels were “a mirror at the side of the road” reflecting reality. But such a mirror can’t show you the world or yourself from a viewpoint you never saw it from before, as science fiction does.

Serious science fiction is just as much about the real world and human beings as realistic novels are.

The thing to remember, however exotic or futuristic or alien the mirror seems, is that you are in fact looking at your world and yourself. Serious science fiction is just as much about the real world and human beings as realistic novels are. (Sometimes more so, I think when faced with yet another dreary story about a dysfunctional upper middle class East Coast urban family.) After all, the imagination can only take apart reality and recombine it. We aren’t God, our word isn’t the world. But our minds can learn a lot about the world by playing with it, and the imagination finds an infinite playing field in fiction.

Along in the sixties it became important to a lot of us, especially women and gays, to try to get a better idea what exactly “gender” consisted of. “Him Tarzan, Me Jane” no longer seemed quite adequate. The science-fiction mirror offered itself to me (and Theodore Sturgeon, and Samuel R. Delaney, Vonda McIntyre, Joanna Russ, and many others) as a great way to get a different angle on the whole thing. Cognitive estrangement can help you develop new cognitions, wider understanding.

And that, as you say, offers a writer a desirable freedom. To me, though, it’s not a release or escape from our world. My world is all I have to make my stories from, my people are the only people I know. But by making up worlds and peoples, I can recombine and play with what we have and are, can ask what if it were like this instead of like this — What if nobody had a fixed gender, as on the planet Gethen? What if marriages, instead of two people and one couple, consisted of four people and four homo- and heterosexual couples, as they do on the planet O? If nobody in a world had ever waged war, how would people and daily life in that world differ from ours, and in what ways?

Much of my science fiction is, in this sense, anthropological. My father was an ethnologist, who learned from the Indians of California that California could be inhabited in a very different way from how we inhabit it — many different ways. I send imaginary people to imaginary planets to learn other ways in which we might inhabit our own. I feel some urgency in obtaining this information, since we’re inhabiting our planet in an increasingly destructive and unwise way.

MC: Are the distinctions between science fiction, speculative fiction, and fantasy still interesting to you? I’ve read interviews in which you discussed them in the past, and would be glad to have you comment on your current thinking in that area, unless of course you’re no longer particularly concerned about it.

UKLG: That is in fact the case, Michael. I felt obliged for so many years to protest, to rant about those distinctions — genuine and useful ones — being misused as value-judgments. Now the judgmentalism is dropping out of them, and that’s great. I don’t have to worry, I don’t have to rant. Whew!

MC: I teach an undergraduate course called Reading Fiction for Craft, and your short story, “The Ones Who Walk Away From Omelas,” has been on the syllabus from the beginning. My students and I discuss that story relatively early in the semester, during a class meeting I call “The Rules.”

I remind them throughout the semester that there are no rules, there are at best a few general principles that seem to work, for fiction writers, some of the time. And, okay, sometimes to work more often than not.

Your story is offered to them as an example of just how far a writer can stray from even the general principles, and still produce a remarkable, absorbing, moving story.

I hope you won’t mind my telling you that “The Ones Who Walk” is one of the few stories that’s always a huge hit, with every student, every semester.

We discuss many aspects of that story, prominent among them its disregard of what I suppose I’ll call “writerly good behavior.” You address the reader directly. You remind the reader that a story is an invention, and that the writer is usually trying to figure out what will be most effective to readers, although that effort is “supposed” to be concealed. You eschew central characters. And the story presents a genuine moral dilemma, a more or less insoluble one, in a medium in which writers are “supposed to” remain at least outwardly neutral, philosophically and politically. Or, rather, to be subvertly philosophical and political; to conceal the thinking under the characters and events.

Would you talk about that story? About how you arrived at it, how you developed it, whether you had doubts about its unorthodoxy after you’d finished it?

UKLG: Honestly, orthodoxy concerns me about as much as it concerns your average jackrabbit. I only follow rules that take me where I want to go. If there aren’t any rules, I make up my own (and follow them strictly).

Honestly, orthodoxy concerns me about as much as it concerns your average jackrabbit. I only follow rules that take me where I want to go.

The two books I really worried about being too far outside critical and reader expectation were The Left Hand of Darkness (I was totally wrong, it flew from the start) and Lavinia (I was partly right, alas, but it seems to be finding its readers.) But I don’t remember worrying about Omelas.

While writing it I thoroughly enjoyed defying all the conventions, dancing little metafictional jigs on the grave of the Self-Concealed Writer.

I sent it to my then agent, Virginia Kidd, who could have sold Das Kapital to a Texas Tea Party Congressman. She sold it right off and it’s been reprinted steadily ever since. Teachers in all kinds of fields — literature, philosophy, sociology, economics — use it as a discussion-starter. It poses a frightening moral question (which William James and Dostoyevsky both asked, and which is directly relevant to our society) and offers no direct resolution. This makes some students so angry and unhappy and unsatisfied that they want to complain about it, and then other students want to explain it to them. . . .

“Writerly good behavior” is a nice phrase. It makes me think about when I was an entering freshwoman at Radcliffe College (now subsumed in Harvard) in 1947. The President of the College paternally informed us girls that we were there to learn gracious living.

Yeah. Uhhuh. A bunch of crazy, graceless, passionate, adolescent female intellectuals ravenous to learn everything Harvard would teach us — and we were there to learn good behavior? Ladylikeness? How set a pretty table and pour tea?

Fortunately, Harvard gave us a superb education, which equipped some of us, at least, to begin to learn how and when to overturn the table and the tea urn. And why.

MC: Is there any question you wish an interviewer would ask, and hasn’t yet?

UKLG: I don’t think anyone has asked me about the relative importance of human beings and nonhuman beings in my fiction and poetry. For instance, the rather large place animals and trees occupy in my writing. Novels consist of human relationships, but I often extend those relationships to include other creatures, including forests, dragons, and rats. My poetry has a lot of geology in it — rocks. I seem to move easily out of the human-centered universe. Maybe I enjoy escaping from it? I don’t know…

Thank you, Michael Cunningham and Electric Literature, I have enjoyed this conversation.

Buy The Lathe of Heaven for just $3.99

Originally published at electricliterature.com.