interviews

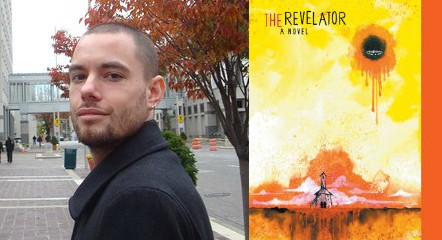

Violent Histories: An Interview With Robert Kloss, Author Of The Revelator

Robert Kloss’s novels take an unorthodox look at a violent strain in American history. His earlier novel The Alligators in Abraham followed one character from the Civil War through the early days of the 20th century, and featured hallucinatory interludes, an exploration of the racist politics of the time, and ill-fated polar expeditions along the way. His new novel The Revelator takes as its central character a man who graduates from assorted low-level crimes to founding a religion in the mid-19th century. Here, too, are surreal visitations, violent clashes, and the rise of fanaticism–it’s a searing and often phantasmagorical work.

Increasing the unpredictability of Kloss’s fiction is his use of the second person, which has the effect of pinning the reader to an increasingly unhinged point of view. It’s hypnotic and terrifying, a window into segments of history that many of us might prefer to forget. Kloss and I exchanged a series of emails in which we discussed the roots of his fiction, his historical inspiration, and much more.

TC: Both The Revelator and your earlier novel The Alligators of Abraham are largely set in the 19th century. What attracted you to this period of history?

RK: Well, I think partly the attraction comes from early on in my life — I always found photographs from that period very haunting, strange. And that’s not just because people back then took staged pictures of their dead infants — even photographs of men posed in a general store or a woman in a hat standing next to a horse takes on a strangeness. It’s a society and a people that we recognize as similar to our own, but something is off. Partly it’s the awkwardness of the posing — there’s a weird formality and severity to their faces and postures. There’s the distance of time and the recognition that those people and the world they inhabited and created is long dust, even as it went into the formation of our own. So just looking at those people going about their lives feeds into my ongoing reveries about mortality and life — and I do enjoy looking at those people long dead and yet captured and immortalized in that single moment in time and wonder about them and I always have. There’s also the idea that the 19th century, for the most part, is where the United States came from. We can point to different moments in that century and recognize the acceleration of history and technology and industry and pinpoint where things went right or wrong. I suppose my books focus on the “where things went wrong” side, but some good came out of those years as well.

TC: Do you remember what the first artifact from the 19th century that you came across was?

RK: No, but I lived in Massachusetts for 12 years, and everything out there is an artifact. You’re constantly made aware of the past, of the living past… every building is an artifact or monument. Even a Dunkin Donuts might be housed in a three hundred year old building. I’m originally from Wisconsin, so moving to a place with that much living history is very affecting. And then, just about everything is an artifact anyway. Birds are supposedly derived from dinosaurs, for instance, and I think about that whenever some crow swoops over my back deck.

TC: You’ve written several novels in the second person. What are some of the challenges of this? And how do you best shape a character when using this approach?

RK: I’ve been writing in the second person mostly exclusively since the summer of 2010, and entirely in the second since 2011, when I started The Alligators of Abraham. I find writing in the perspective very liberating — there are no restrictions. I believe in challenges, not restrictions, and in a way my challenge is always how to write in the most authentic, liberated way possible — and for me using the second person was one of those keys, and writing in period was one of the others.

For me there’s something almost primordial about the perspective, as if addressing the “you” creates the world out of the dust…

I have overthought the perspective in the past, because the perspective is less conventional — for instance, in the first draft of The Alligators of Abraham I tried justifying the perspective within the narrative by establishing the speaker’s identity, and I quickly realized that was a mistake. I think the second person works best when the speaker is somehow removed from events — when the speaker is greater or more powerful than the protagonist or is looking back on events with a wider perspective, a longer view. For me there’s something almost primordial about the perspective, as if addressing the “you” creates the world out of the dust, and I suppose in a way it does.

As far as shaping character, my philosophy is that character should move within the narrative, not drive the narrative. We have the illusion that we are in control of our lives, that we determine events, but we do not. We are at the mercy of forces far greater than ourselves. I actually prefer a passive character — observing, reacting, being buffeted around and responding to the world. The universe is active. Society is active. History is active. God moves, and characters respond, grope, search, wander. And slowly, in figuring out why that response happened, the character is revealed. But that revelation is less essential than the drive of historical event.

TC: In terms of using the second person: can you foresee a time when you might be interested in working in either the first or third person again?

RK: I’m open to any approach if it fits the material. Both The Revelator and the novel I wrote after it, The Woman Who Lived Amongst the Cannibals, contain sections in the third person and Cannibals has some first person as well (although second is again dominant). I did try out both third and first for my new book but eventually I went back to second — it just felt right. I suppose as long as second feels right I’ll stay faithful and the moment it feels wrong I will have to find the next perspective. I should mention that I’ve thought about doing something in the first person plural at some point, but I have no special plans right now.

TC: Is your next project also an exploration of history?

RK: Maybe? The manuscript I finished after The Revelator is fairly direct exploration of history, pre-history, post-history. So the idea of history and what it is and how it is shaped was really, directly, on the front of my thinking for almost two years. I’ve backed away from it, a little, with the new book, but I’m sure those ideas will inform my thinking… I did not reach any definitive conclusions about anything I wrote about. And now that I’m out west (I moved to Boulder, Colorado a couple weeks ago), you are constantly confronted with the juxtaposition of these mountains that are incredibly old and the remnants of what counts as history out here — a house constructed in 1890, for example, or the remnants of an old mining town on a mountain. So the idea of being human, being mortal, and being in the shadow of forces and influences much older and grander and (yet) more or less impermanent is always on my mind.

To answer your question a bit more directly the new novel is set in (roughly) the 1850s to… a time period probably post-reconstruction, but it’s all very loose and uncertain right now. So it’s a period novel and it’s a novel about early America, while also being a novel about contemporary America. It’s in the second person. But that’s all I really know right now.

TC: The Revelator can be described as a violent, hallucinatory take on the early days of Mormonism. What first drew you to this subject?

…the Mormon story seemed the largest and the grandest and in many ways the most American.

RK: I wanted to write a novel about the end of time — not a post-apocalypse novel, but a novel about the apocalypse. So the interest in Mormonism came out of my research into doomsday cults and doomsday scenarios. Eventually most of that material was dropped, but I suppose in general I’m drawn to stories about extreme beliefs, extreme individuals, extreme actions, and the Mormon story — the Joseph Smith story and the story of the rise of the church — is a story of so many extremes. I did draw from other traditions, other cults and religions, but the Mormon story seemed the largest and the grandest and in many ways the most American. There’s something very crucial about that national moment that illustrates a lot about where we are as a nation today.

TC: Your novels incorporate real historical figures, and at the end of The Alligators of Abraham, you include a list of works that you referenced. To what extent do you feel compelled to stay historically accurate?

RK: Oh, I’m not compelled at all. I’m not a scholar and I don’t write history — I write fiction. Although I did want to credit my references in the earlier novel, Alligators and The Revelator both abuse and manipulate history to the point that they are something other than historical fiction… fictional history, maybe. Researching for The Revelator I read more about Abraham from the Old Testament and other religious and political extremists than I did about Mormonism. And I ultimately place more importance on the role of imagination in novel writing than research and accuracy. I don’t think I could ever write like, say, William T. Vollmann, although I greatly admire his work and I obviously wish I could write books like his.

TC: As someone who’s read Ghosts of Cape Sabine, I was curious–how did you come to work that bit of history into The Alligators of Abraham?

RK: I keep my eyes and ears open, wherever I go, whatever I do; I’m always thinking about the book I’m working on, even if a little in the back of my mind, always working out problems or looking for material to add. I’m sure this is how many writers work, and it makes sense. You just naturally come into contact with the material you didn’t know you needed — the perfect information or perfect story or perfect bit of history or fact you’d somehow been moving toward. I walk library aisles, bookstore aisles, a lot, waiting for an impulse to grab a particular book. And I watch television programs on PBS and History Channel and whatever other station devote any time to “informational” programing. For instance, the Almighty’s black mountain in The Revelator comes from a program about Mount Fuji — a mention about the forest of suicides at the base of the mountain touched off something in me. It was exactly what the novel needed, and it was exactly what I had been looking for, and there it was. I read Ghosts of Cape Sabine after watching a program on PBS devoted to the Greely Expedition, and it was exactly what I needed for Alligators. I had been planning something in the novel for Lincoln’s plan to deport freed slaves, and the two ideas somehow collided perfectly when I saw the program. It just made sense.

TC: The Revelator explores the boundary between mysticism and self-interest; where, for you, does the line fall?

Rare is the holy fool, my ideal mystic, that raving fellow who falls from society and perishes in the wilderness or is consumed by a bear or swarmed by bees.

RK: I’m not sure. My first answer is that they are not compatible. Self-interest naturally corrupts and perverts and packages. How watered down or malformed can something become before it loses its essence? I lived in Salem, Massachusetts for nine years, and so I’m all too familiar with the charismatic mystic, the smooth mystic, the self-interested mystic, the mystic on a poster and the mystic in a shop window, the mystic as gossip. I don’t believe what you get in those shops is mysticism as much as commerce and entertainment and, often, outright fraud, but there are those who find some peace in having their palm read, or, at least, a greater sense of something beyond themselves. Of course, a psychic shop in Salem is on a different level than a cult leader who calls for a mass suicide or a megachurch leader who makes millions off the sick and weak and elderly. They all seem powered by the same motivations and impulses, if different levels of them, and they all seem on the American wavelength. Rare is the holy fool, my ideal mystic, that raving fellow who falls from society and perishes in the wilderness or is consumed by a bear or swarmed by bees.

TC: In the final third of The Revelator, the religiously-motivated violence becomes overwhelming at times. How did you find an approach to this that felt right?

RK: The level of violence and the kind of violence is probably the most historically accurate part of the book and I wanted to get it as right as I could — so I leaned a bit on historical accounts, when they existed. I certainly looked to how McCarthy handles violence in Blood Meridian. I also looked at accounts of cult and extremist related violence — for instance, I read about Jim Jones and the oppression and mass murders of Stalin-era Soviet Union. I tried to be as honest as possible. And I tried to be overwhelming, yes. I tried to convey with language as much as I could the horror and enormity of the violence. I did not want to write about violence and horror and oppression in this book in a half-stated way. It would have been dishonest to do so.

TC: You’ve worked on several projects with artist Matt Kish. How did you two first meet? How would you say that your working relationship has evolved over the years?

RK: I knew of (and greatly admired) Matt’s work from his Moby-Dick project, but we did not talk until my publisher at the time, J.A. Tyler at Mud Luscious Press, approached him to illustrate the cover for The Alligators of Abraham. That was about four years ago now. To this point he’s illustrated two more of my books — The Desert Places (co-authored with Amber Sparks) and now The Revelator. And I think the process was fairly similar in every case. I approached Matt to see if he was interested and then I let him set the terms. I gave him the books and let him do what he wanted with them. He decided what he would illustrate and how he would illustrate it. Limitations were set by the publishers are far as size and color, but I set no limits or criteria — I trust Matt and his vision completely. But that hasn’t changed — I knew he was a great artist from the first time I saw his blog and I also knew from the first that we had similar visions, even if we were working in different mediums, with different languages, and he had gone further in his.

We are also working on an ongoing bestiary project (that I’ve fallen behind on) where Matt illustrates and names a fantastic creature and then I interpret the beast with my writing.

I watched the Ralph Steadman documentary, For No Good Reason, about a year ago, and I found Steadman’s relationship with Hunter S. Thompson quite fascinating — the two worked together very closely, they went on adventures together. Matt and I have never met, other than a Skype session that we did through a third party, and maybe we never will. We’ve never spoken on the phone to each other. There’s always a little distance in our collaboration — and I like that. I don’t think two artists, especially artists who are close enough in sensibility, should get too close to each other. You become too friendly, maybe, and you lose some of the edge that should go into a project. Whenever I approach Matt about illustrating something or whenever I send him a piece for the bestiary project I feel an anxiety and dread that my work is not up to his standards. Because I see him foremost as a great artist and not a person that I am overly comfortable working with — and I want to maintain that. I think our working relationship, as stands, allows for the right amount of anxiety and dread.