essays

What Fiction Writers Can Learn from Comedy: on reading Poking a Dead Frog

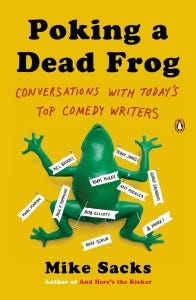

If you read essays by and interviews with fiction writers, you can learn a lot about their processes; what inspires them, how they work, how the real world influences their work, and if autobiographical elements made it into the work. When somebody like Michael Silverblatt is interviewing a fiction writer, you learn tidbits that can enhance the reading experience. Even looking at pictures of where writers work can be endlessly fascinating to some. Personally, I can’t get enough of hearing what makes writers tick, but I was a little surprised when I closed Poking a Dead Frog: Conversations With Today’s Top Comedy Writers, and realized that it’s one of the most fascinating books about the process of writing in any genre I’ve ever read. It shows just how closely related fiction and comedy writing truly are. Editor Mike Sacks reveals that despite the fact that some writers pen novels or short stories and others write jokes for sitcoms, in the end, writing is writing. Sacks accomplishes this via thoughtful yet easygoing interviews with comedians and comedic writers, including one of the best interviews with George Saunders I’ve come across. Take this exchange:

Sacks: I don’t always sense compassion when it comes to humor or satire. I’m not sure if they don’t have full control of their toolbox or if they’re just not compassionate. Can satire work if the writer isn’t a compassionate person?

Saunders: Sure. I think a harsh truth can be compassionate, in the sense that it speeds us along from falseness to truth. So, if a friend is wearing something ridiculous, you can say, “You look like an idiot,” and maybe that will save him. I think we wouldn’t want to assume that compassion is always gentle.

Saunders is part of the small minority of fiction writers in Poking a Dead Frog, but he’s game to let Sacks lead the conversation to fit the book’s parameters. It might seem odd to see Saunders’s name alongside comedians like Mel Brooks and Patton Oswalt, and television writers like Todd Levin and Megan Amram (although both Levin and Amram also have books out as well), but the conversations and advice pieces are so complementary that going from Marc Maron to Saunders doesn’t read awkwardly at all.

Filled with plenty of illuminating facts and behind-closed-door secrets, Poking a Dead Frog showed a different side of writers and how they work, but it also left me wondering why comedy people don’t dabble more in fiction, and why fiction writers don’t let comedy guide their work more often. The conversation with author Bruce Jay Friedman serves as a perfect example of this. Friedman, whose first novel Stern, released in 1962, is described by Sacks as being, “Along with Kurt Vonnegut…one of the pioneers of “dark comedy.” And while I love good satire, I crave novels that make me laugh about the grimmest parts of life. Sadly, those books are far and few between. Sam Lipsyte’s The Ask, Fiona Maazel’s Woke Up Lonely, and Adam Wilson’s Flatscreen all fall under that category, but most contemporary fiction isn’t concerned with being funny. And I’m totally fine with that most of the time.

My own first encounter with Friedman was picking up a copy of the 1965 anthology he edited, Black Humor, while I was rifling through a Salvation Army store when I was a teenager. I recognized a few of the names, and at the time, had read books by two of them: Vladimir Nabokov and Joseph Heller. I’d eventually seek out more of Friedman’s books, along with some of the other writers included in the collection, including Terry Southern, J. P. Donleavy, and Thomas Pynchon, all in an attempt to understand how any of the authors Friedman selected for the book could be considered humorous. As Friedman put it in the introduction: “I am not sure of very much and I think it is true of the writers in this volume that they are not sure of very much either.” Friedman goes on to try and do his best to explain why those writers in the 1960s were funny to him. When I read his words over thirty years later, I had a difficult time understanding how any of those writers could make him or anybody else laugh; but then again, I had a very narrow teenage focus. This was also the period of my life (around the age of 14) when I also said, “This shit isn’t punk,” upon listening to the band that pretty much invented punk, The Velvet Underground. Much like I once thought punk only could sound like Minor Threat, I thought humor was supposed to make you instantly laugh, like a reflex. I didn’t get humor, and the work of some of the greatest writers of the 20th century was lost on me.

I got older. I experienced and learned things. Eventually I came to understand that comedy comes in all different shapes and sizes, and that great humor writing is reflective of its time. In the case of Black Humor, the broken promise of the post-war world and its descent into chaos of the 1960s required a different kind of humor.

Take books like Ulysses or Portnoy’s Complaint: I don’t know if James Joyce or Philip Roth meant to make people laugh, make them uncomfortable, challenge society’s norms, or just write great fiction that happened to do all of those things, but all of those things ended up happening. In his recent interview with Marc Maron on the WTF Podcast, Paul Thomas Anderson pointed out Pynchon was probably just as influenced by comedians Spike Jones and Lenny Bruce as he was any novel, and described his writing as, “Compassionate but upside down.” Did Pynchon hope to make people laugh as they tried to keep track of all the characters in his books? While I don’t know the answer to that, Anderson interpreted it that way, taking his directorial and writing cues for Inherent Vice not from Stanley Kubrick or some Italian guy from the 1960s. Instead, as critics noted, his adaptation “tips into, like, Zucker Bros” territory. How many other novelists can you name whose work gets one of the day’s premiere directors to go from There Will be Blood to shots that remind people of The Naked Gun? I mean, I guess anything could be funny if you slant it the right way. Look at Kafka for long enough, and Gregor Samsar’s day seems somewhat hilarious. “Oh shit, I woke up as a bug. #FML.” Meursault in The Stranger by Camus or Anton Petrovich in Nabokov’s short story “An Affair of Honor”? I’d like to consider these works proto-Larry David.

On the other side of the coin, comedians and comedy writers don’t usually venture too far out to shore. A few years ago, Chris Gethard put out the book A Bad Idea I’m About to Do, that, in my mind was probably one of the best books written by a comedian. Gethard’s personal essays, his tone, and his delivery, made me laugh and were a delight to read. The same goes for books by Julie Klausner and Mindy Kaling. Yet aside from Jack Handey, who you might know best for writing classic SNL skits like “Deep Thoughts” and “Unfrozen Caveman Lawyer,” Simon Rich, and B.J. Novak whose collection of short stories, One More Thing, took me by surprise, I always wonder why more comedy writers don’t try their hands at fiction.

Mike Schur whose resume includes writing and acting on the American version of The Office, as well as co-creating and writing shows like Parks and Recreation and Brooklyn Nine-Nine, talks a good deal about David Foster Wallace in his discussion with Sacks, and it makes me think of his shows in a different light. Take one of the more interesting observations that Schur — who wrote a thesis on how Wallace’s Infinite Jest and Pynchon’s V. “served as bookends for a type of post-modern fiction that dealt irony and identity cohesion” — makes the point that Wallace deals a lot with the themes of sincerity and honesty, something you see his characters searching for while trying to make you laugh. Two things that Schur says are tough for comedy writers, “because sincerity is the opposite of ‘cool’ or ‘hip’ or ‘ironic.’” Obviously as a fan of all of Schur’s work, I’d never ask him to quit his day job to go finish that novel he’s had stashed away. But with his interest in fiction, I can’t help but wonder if a guy who has been involved with some of the most acclaimed and beloved comedies of the last decade writes fiction every now and then. Because what is Pawnee, Indiana, but a fictional town filled with fictional people?

Ultimately, of course, the one thing that separates fiction writers and comedy writers is that comedy writers usually write with teams. There isn’t one person writing jokes for David Letterman or Jon Stewart; there are a bunch of people. You see it joked about on shows like 30 Rock, where the writer’s room is enlivened by the very collaborative energy that gives Poking a Dead Frog its legs. Writing fiction, on the other hand, is a largely solitary exercise, confined to a desk or a table in a coffee shop with headphones on. Yet the two forms of writing can work well together and have more in common than we might think. One of my favorite exchanges in all of Poking a Dead Frog sums is something most writers I know can relate to. When Sacks is talking with Cabin Boy writer and director Adam Resnick, Resnick tells Sacks about the prostitutes that live next door to his writing office in New City:

Resnick: I liked it at first, but it’s just annoying now. And they both have a habit of letting the door slam whenever they leave, and my whole apartment shakes. Prostitutes can be so boorish these days.

Sacks: The glamour of being a writer.

Resnick: I guess.