Craft

When Popular Fiction Isn’t Popular: Genre, Literary, and the Myths of Popularity

Genre Vs. Literary Has Nothing to Do with Popularity

Is the novel dead? Are MFA programs worth it? Can characters be unlikable? Genre or literary fiction? Is the novel dead because MFA programs are fighting a genre war with unlikable characters?

Sometimes it feels like there are only five topics the literary world can write about, but despite the sheer number of think pieces on these subjects, there tends to be very little said in the way of actual facts. When we get into a debate like self-publishing vs. traditional publishing or “genre” vs. “literary,” we’ve wandered into the book world version of conservative vs. liberal. Arguments revolve around feelings, constantly redefined terms, and moving goal posts rather than any interest in truth or understanding.

Take Damien Walter’s article in The Guardian claiming that “Literary fiction is an artificial luxury brand but it doesn’t sell.” Walter pretends he is attacking the literary snobbery, yet the piece is overtly condescending toward readers of books Walter looks down upon. For Walter, people who read “high-end literature” only do so because they (falsely) think it “make(s) you look cool” while readers of genre fiction are people who buy books “because they love them.” It isn’t just that literary fiction doesn’t sell, but its readers are poseurs who don’t even actually like books! Claiming anyone who reads books you don’t like is a fake reader who buys books out of bad faith is about as snobbish as you can get.

There are some other nonsensical arguments in Walter’s piece, such as his claim that David Mitchell — most famous for his genre-bending Cloud Atlas — is being penalized for “wander[ing] off the reservation” of literary fiction and experimenting with genre with his current book. That’s kind of like arguing that David Lynch will be penalized for being weird in his next film.

Walter also defines literary fiction as “an artificial luxury brand” — I’d love to know what a “natural” luxury brand is — “the Mercedes, the Harrods and the Luis Vuitton of high culture.” But those luxury brands are ones that cost more and are marketed to affluent customers as socioeconomic status symbols. Literary fiction books mostly cost the same as SF or thriller novels. Even the idea that literary fiction is favored by the actual elites of society is highly suspect. You are far more likely to find John Grisham and Dan Brown novels in the houses of politicians, lawyers, and hedge fund managers than the works of Lydia Davis and William Gaddis.

You are far more likely to find John Grisham and Dan Brown novels in the houses of politicians, lawyers, and hedge fund managers than the works of Lydia Davis and William Gaddis.

But what I’d like to focus on is the oddly persistent myth that genre fiction is “popular fiction” and that literary fiction is pointless and obscure. Or, as Jennifer Weiner regularly argues, that book critics and literary awards overlook the kind of fiction that real readers actually like. The idea even comes up in intra-genre wars, such as when the conservative SF Sad Puppies — who caused the biggest stir in science fiction this year by organizing a coordinated Hugo voting campaign — argued that science fiction is being destroyed by books “long on ‘literary’ elements” and short on what makes science fiction “popular.”

There is an odd cognitive dissonance that happens in these conversations, where we are simultaneously supposed to believe that literary fiction is “mainstream fiction” and genre fiction is “ghettoized,” and also that literary fiction is a niche nobody reads while genre authors laugh all the way to the bank. Throw into the mix a recent Wall Street Journal article on the increasingly practice of giving million dollar advances to literary debut novels, and you can see that the truth of the matter is pretty unclear.

A Note on My “Team”

Since the genre/literary debate is such a political one, I should probably lay out my cards. I’m an avid reader of both genre and literary fiction. My debut book was generally reviewed as “genre-bending” and featured literary realism stories alongside stories about cosmic horrors, fairy tale journeys, and zombies. Earlier this year, I co-edited and published a science fiction anthology that featured both “genre” and “literary” authors. I’m hardly of the opinion that books shelved as genre are inherently inferior to those shelved as literary. Artistically, I’m rooting for both sides.

Ultimately, though, I think that sales are an entirely irrelevant question in art (more on that at the end). My favorite books in both the genre world and the literary world are never the ones that sell well. What’s popular in any field is largely a matter of money and luck. My interest in this issue is with the persistent misconceptions and contradictions that abound.

How the Popular Pie Is Divvied Up

Is genre more popular than literary fiction? If you combine every single non-literary genre together, the sales are the vast majority of the market. However, the same people who make this argument typically say “literary fiction is just another genre.” So this is akin to saying that US-based NBA teams score more points than the Toronto Raptors. Sure, it’s true, but it doesn’t actually tell you anything about how good or bad the Raptors are. Non-superhero films sells more tickets than superhero films. All foods that aren’t pizza sell more than pizza. That doesn’t mean superhero films and pizza aren’t popular.

So this is akin to saying that US-based NBA teams score more points than the Toronto Raptors.

So are individual genres more popular than the genre of literary fiction? Well, that depends on which genre you mean. Despite the regular conflation of “genre fiction” with “popular fiction,” most genre fiction is not popular at all. I don’t merely mean that most books that are published in the various genres are unpopular — although that is certainly true. Most books don’t sell much period. I mean that most genres and subgenres are niche markets. You rarely see steam punk or bizarro fiction titles flying up the bestseller list. You rarely even see westerns or horror novels. By what measure are they “popular” fiction when literary fiction, which does regularly reach the bestseller lists, is not?

In reality, the bestseller lists are completely dominated by thrillers/mysteries, romance novels, and YA. Literary fiction titles are a regular staple. Other genres — westerns, hard SF, non-YA fantasy, and horror novels not written by Stephen King — are much less likely to appear. If you scroll through the New York Times combined print and ebook list, you’ll see a couple literary titles each week sandwiched between a bunch of big name thriller and romance authors like Grisham, Roberts, and Patterson. You’ll also see a handful of traditional adult SF or fantasy titles, but they are typically works that have been adapted for TV or film, such as Andy Weir’s The Martian. One could argue that Anthony Doerr and Jonathan Franzen are exceptions, and of course they are. But George R. R. Martin and Stephen King are exceptions in their genres too. The bestseller list is 100% exceptions.

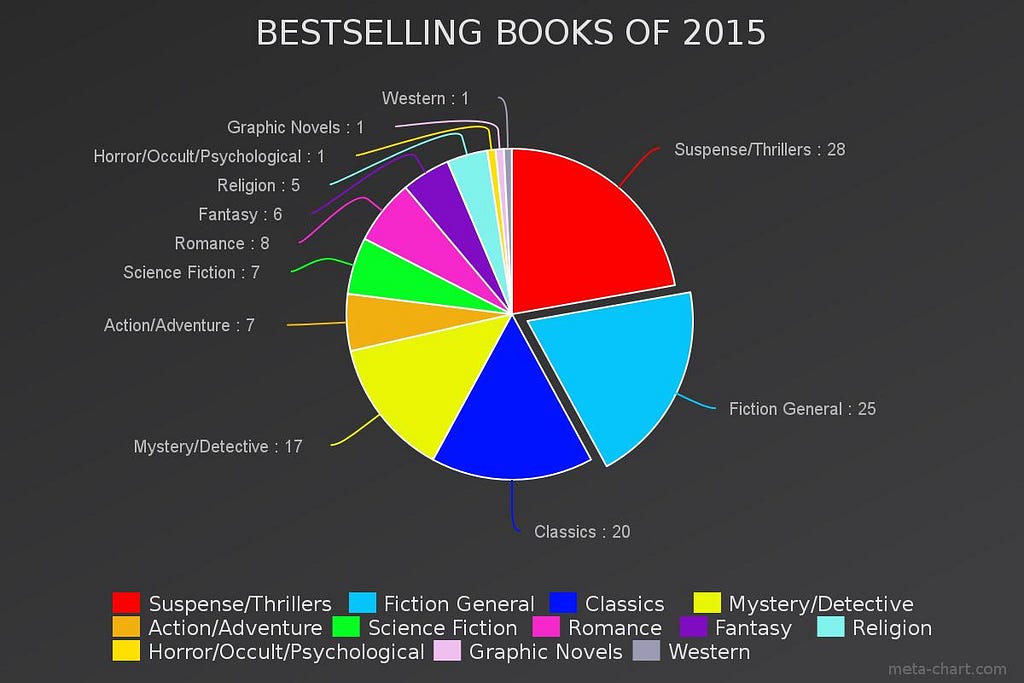

Using Neilsen BookScan — the industry’s sales tracking system that captures most, though not all, of the print market — I looked at the different categories for adult fiction that have sold more than 50,000 copies. (Children’s books, middle grade, and young adult are an enormous part of the market, but that’s a topic for another post.) For adult fiction, Suspense/Thrillers had 28 titles that made the cut, and Mystery/Detective had 17. Fiction General had 25 and Classics had 20 titles. None of the other genres had double digits, not even Romance. Western and Horror/Occult/Psychological each had 1 title that made the cut. Fantasy had 6, but only one that wasn’t written by George R. R. Martin.

The category Fiction General in BookScan includes many titles that Weiner would call “commercial women’s fiction.” Still, about half of those high-performing titles would be considered literary fiction (such as Doerr, Adichie, Ferrante, and Franzen) and basically all the Classics (Fitzgerald, Hemingway, Salinger, etc.) are literary titles. It would probably be fair to clump Mystery and Thrillers together, and several of the Fiction General titles could be shuffled to Romance, but no matter how you slice it, literary fiction is one of the larger chunks of the popular adult fiction pie.

A Note on BookScan and Those Numbers

BookScan is estimated to account for somewhere around 75% of the retail print market, so these does not tell the whole story. Some genres, like science fiction and romance, do well in ebook form. Still, it gives a good estimation of the relative selling power of different books.

I’m sure some readers will think it unfair to include classic titles. But is popularity only measured in the short-term? Is a book that sells 100,000 copies in a year, but is quickly forgotten, more “popular” than a book that sells 10,000 copies a year for 50 years? Even focusing only on contemporary titles, literary fiction makes up a larger percentage of popular books by this measure than most genres. (FWIW, many of the bestselling genre books are also from previous decades. For example, Michael Crichton’s Jurassic Park and Agatha Christie’s And Then There Were None are listed in Science Fiction and Mystery/Detective in BookScan.)

Looking at the BookScan titles also shows the murkiness of genre categorization though. One of the best selling books in Science Fiction is Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, a finalist for several major literary awards (and also the ire of Sad Puppies types). Plenty of other books could be categorized in different genres, or multiple genres at once. Genre distinctions are anything but clear.

What’s Popular Is Whatever You Want it to Be

The above is only looking at the most popular books, not the entire market overall. Some genres do better or worse in the long tail and are larger or smaller slices of the entire industry. And then again, some genre readers are more rabid buyers of books. Romance readers are infamous book devourers, and thus their portion of the reading population will be different than their portion of sales. In short, it is complicated. But the above numbers give a good overview of how the popular break-out books break down.

However, too often it seems their interest in “popular books” is actually only an interest in books that are popular in the styles they like. Take this interview with Weiner and Jodi Picoult from their famous Franzenfreude. The two authors bend their arguments into bizarre shapes trying to define what “commercial” fiction is in opposition to Jonathan Franzen, an author whose last two books sold at Stephen King levels (the #5 bestselling and #8 bestselling books of their respective years). Many of the titles Weiner and Picoult slag on here and elsewhere actually sell more copies, and are thus more truly “commercial,” than books they say are overlooked. Weiner says “How seriously am I going to take the paper’s critics when they start beating the drums for Gary Shteyngart” and then mocks Shteyngart’s BookScan numbers for the first week of his (then) new novel. Yet all three of Shteyngart’s novels have sold in six figures, making him a pretty darn popular novelist in any genre.

(Picoult also has very ahistorical comments about the popularity of famous authors like Jane Austen. But again, the facts are less important than truthiness in these debates. Austen may have, in actuality, been read mainly by the elites of her day–an era when about half of England’s population was illiterate to begin with–but she feels like she should count as a writer who writes for the masses.)

In fairness to Weiner, her main argument is that book review sections, like in the New York Times, don’t review as many commercial women authors as commercial male authors. I think that Weiner has a point, as there is plenty of sexism in publishing and women authors are often not treated as seriously as male authors. And Weiner is correct that romance and “women’s fiction” are not treated with the same respect as other genres. However, I wonder if Weiner conflates different issues, and is practicing a form of literary erasure by implying that women authors in most genres don’t count as women genre authors:

@fischermichael0 That’s my point! If NYT reviews thrillers and mysteries and fantasy, it should also cover women’s genre fiction.

— Jennifer Weiner (@jenniferweiner) September 2, 2015

Most likely, the readership of mysteries and thrillers is largely women — as is true of fiction as a whole — and the idea that the genres of Agatha Christie, Patricia Highsmith, and Ursula K. Le Guin are “male genres” is, to put it nicely, a stretch.

The New York Times is not perfect of course. But I will say that the New York Times does a far better job of covering non-white writers, international writers, and writers of poetry and short stories than the bestseller lists. Their 100 notable book list had a roughly equal gender split. A newspaper that only devoted coverage to popular fiction would be a newspaper that only covered white American novelists.

The (mostly) conservative white men of the Sad Puppies movement, and their more odious Rabid Puppies offshoot, nominated a slate of books that was by and large a list of relatively poor-selling books even as they claimed to be representing popular science fiction. On the other hand, many of the best selling science fiction titles of last year (Jeff VanderMeer’s Southern Reach trilogy, Emily St. John Mandel’s Station Eleven, etc.) were exactly the kind of literary titles the Puppies claimed were making SF unpopular. But to the Puppies it feels like their favorite books should be popular and it feels like literary SF shouldn’t be. Even more so, the Puppies complained that the Hugos were being awarded to people of color, queer writers, and other writers on “social justice warrior grounds.” Yet again, this seems entirely a matter of feeling instead of reality. A scroll through the list of recent Hugo winners shows that most have been white writers, and most have been white men.

Big in an Alternate Reality

When Walter and similar critics call literary fiction’s status “artificial,” they seem to imply literary fiction is being wrongly inflated by literary critics and awards. I’ve heard this argument many times. I must admit I find this idea pretty baffling. Commercial fiction is more likely to have massive corporate marketing campaigns with subway ads and full page spreads in popular magazines. A gushing review from actual literary critic is “artificial” while a Times Square billboard is “natural”?

A gushing review from actual literary critic is “artificial” while a Times Square billboard is “natural”?

The underlying argument seems to be that even if these books aren’t actually popular they are still popular in some theoretical sense, because they are the kind of books that could be popular in some alternative world. (This is essentially the Sad Puppies argument. The SF books they like don’t sell well because the evil Hugos and SF critics are pushing literary novels on the SF public.) In this way, all “real” genre is popular because it is all theoretically accessible and written to be fun and engaging.

Only someone who doesn’t read widely in genre fiction could actually think this. Plenty of genre fiction — especially in the SF, fantasy, and horror worlds — is as inaccessible as the most avant-garde poetry chapbook. Epic fantasy series often include detailed encyclopedias of their fictional worlds, hardly something accessible to casual readers. SF novels are often written in jargon and tropes that outsiders wouldn’t understand. And, most importantly, lots of really interesting, boundary-pushing work exists in the genre world. I doubt anyone would argue Gene Wolfe isn’t a SF author, and I also doubt anyone would honestly say his work is popular fiction. His books are every bit as dense and complex as the most “luxury brand” literary novels you could name, but they swim happily in the sea of genre.

And all that’s as it should be! Some of the most exciting genre work is written only for fans of those niche subgenres. That isn’t a bug, it’s a feature.

The Focus on Popularity Is Horrible for Literature

Which brings up the larger point: the incessant focus on popularity is an artistically-deadening feature of modern discourse. Far too many people tout sales numbers as some kind of armor against criticism, and think that the highest compliment you can ever pay an artist is that their work “sells well.” Sales have essentially no relation to quality. In fact, sales barely even have any relation to sales. By which I mean, books that sell well today are pretty unlikely to be selling well 50 or 100 years from now. How many best-selling titles from 100 years ago do you recognize? (Note: this Winston Churchill is not the prime minster. In fact, the American Churchill was so famous that the British Churchill wrote under the name Winston S. Churchill to avoid confusion. But the former is now totally forgotten while obscure-in-their-day contemporaries of his like Franz Kafka are widely read.)

The massively popular books are very rarely among the best, whether shelved as “genre” or as “literary.” Want to know what the best-selling book of the year has been? Go Set a Watchmen, a cash-grab novel that many have argued was unethical to even publish. The second? Grey, another cash-grab where E. L. James rewrote 50 Shades from a male point of view. (And, yes, Hollywood “reboot” culture is absolutely coming to the literary world in the near future. I mean, hey, it’s popular.)

There is an entire world of literature, quite literally. Yet you would never know it from the bestseller lists, which are populated by the same handful of names year in and year out. Those names are almost entirely white English-speaking men and women. They write in a narrow range of styles and subject matters. We should be extremely wary of anyone who wants book coverage to focus even more on the handful of white American authors who dominate sales.

We should be extremely wary of anyone who wants book coverage to focus even more on the handful of white American authors who dominate sales.

The overwhelming whiteness and homogeneity of popular books is not something that would be addressed by focusing even more coverage on the same handful of popular books. (To say nothing of what it would do to short stories, essay, and poetry collections.)

If you are determined to compare popularity, at least do so with actual facts. But it would be far better if we focused less on popularity, and more on the wide range of amazing books from all genres and corners of the globe that are daily ignored for yet another think piece on already popular books.

Originally published at electricliterature.com.