interviews

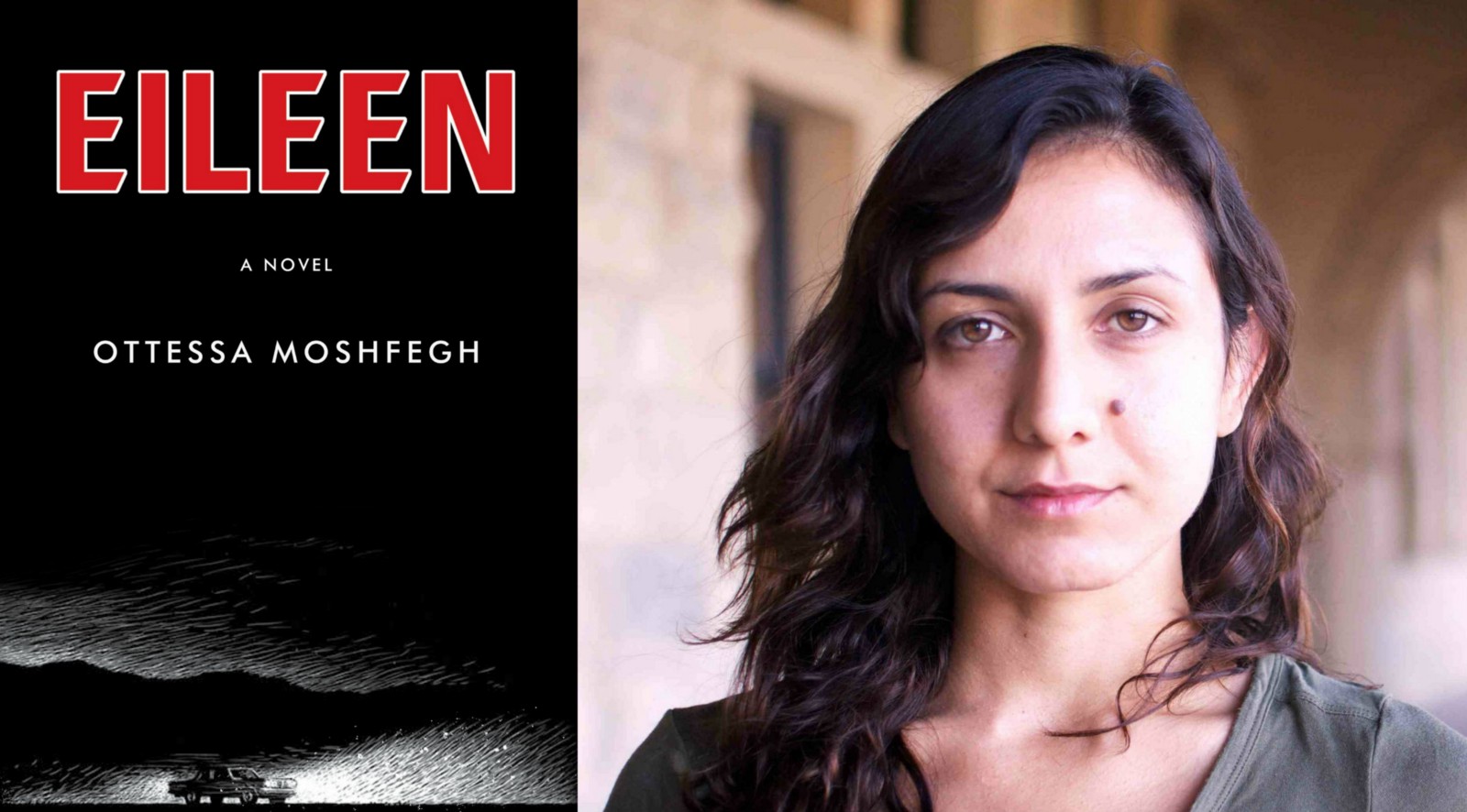

Why We Do Weird Things: An Interview With Ottessa Moshfegh, author of Eileen

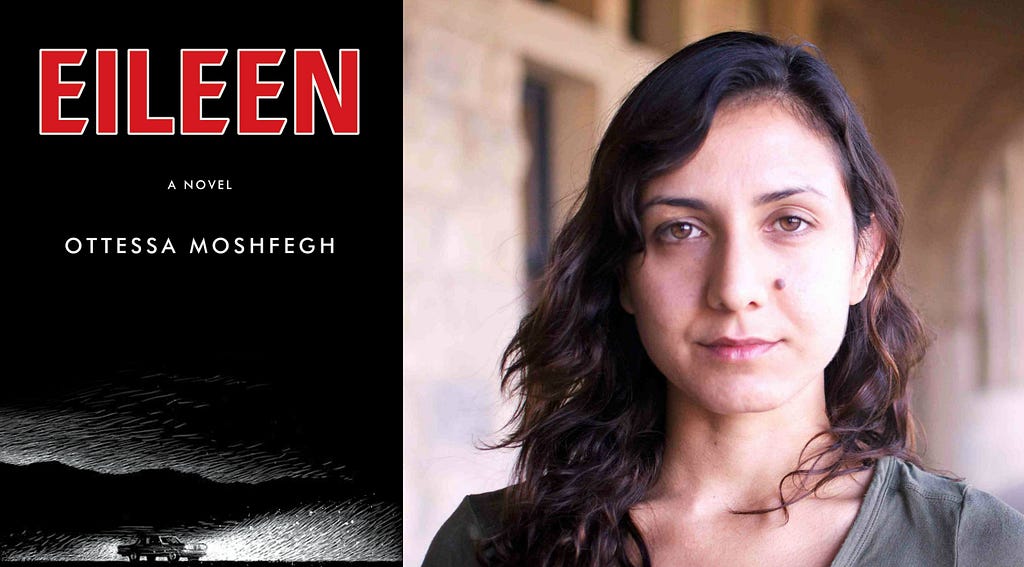

by Megha Majumdar

In Ottessa Moshfegh’s new novel, Eileen, the titular character works at a boys’ prison, lives with her alcoholic father in a town she cannot bear to name, and obsesses over her body’s inelegant systems and secretions.

This character study, however, is also the story of a bizarre murder.

Moshfegh writes, she says, to explore why people do weird things. This interest in the strange — a few striations from the humiliating — shows. In her short-story Disgust, a lonely Chinese man debases himself in his love for a faintly-known woman. In her novella McGlue (excerpted in Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading), a drunk sailor is unable to remember if he has murdered his friend.

The Paris Review has championed Moshfegh’s work, publishing several of her stories, and awarding her the Plimpton Prize in 2013. (Her story, “Bettering Myself,” was also featured in Recommended Reading, recommended by The Paris Review.) The following year, Moshfegh won a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts.

When Moshfegh and I chatted on a rainy day in a Williamsburg coffee shop, she was in the final months of a Stegner Fellowship. We discussed, among other things, feminist writing, embarrassment as a literary subject, and why the uproar over Claire Messud’s “The Woman Upstairs” makes her angry.

Moshfegh was unafraid of disagreement, and our conversation rounded into argument and back. But the most memorable moment came when she spoke, lit up, of the joy of writing: “I can’t tell you how much I love writing, revising, editing,” she said. “It’s a complete fantasy.”

Megha Majumdar: What is really interesting about Eileen is that the book complicates female desire. I was struck by a part in which Eileen thinks that her first time having sex will be, in fact, a forced encounter. She believes she will be raped. That, of course, questions what desire can look like. Did you set out to write a feminist book?

If we go by the mores and values that we see around us, any woman living in this world should hate herself.

Ottessa Moshfegh: You’re the first person to ask me that. Thank you. Everything I write is feminist, because I don’t hate women, I hope. I find it impossible to ignore the fact that we live in a really violent culture. Eileen’s character in particular is a victim of that violence. Not only is she in a completely shitty situation at home, but the whole world is rigged to keep her small and powerless. So I wondered, what would it be like if I exposed what happens in a person’s mind when she is being conspired against, held hostage to society? The mind gets perverted when you live in a state of constant defensiveness. You think there’s something wrong with you. Self-loathing is natural. If we go by the mores and values that we see around us, any woman living in this world should hate herself.

MM: Eileen’s self-obsession can make her an unpleasant person to be with —

OM: I don’t agree. Of all the characters in the book, Eileen is the one I relate to.

People talk about her, like, is this a girl you want to spend time with? But she’s pretty typical. She’s delivered to the reader in an intimate, first-person narrative, so you know what her thoughts are. From the outside, she’s not offensive, though she thinks she is.

She has an inflated sense of her physicality. What I was hoping to capture through the perspective of having Eileen narrate this book at 75, talking about herself at 24, is that her self-perception was inaccurate. It was an effect of living in this world. I don’t think she’s that bad.

MM: All right. Let’s see if the question I was going for could still stand — there are a bunch of characters in the book who are unpleasant. People you wouldn’t want to hang out with. Unlikeable characters, basically. I wonder if you remember the debate over unlikeable characters — if women are always expected to write likeable characters, and so on. Do you have some hope for how your book might engage with that debate?

OM: I hope that people might see how ridiculously sexist that is. And it’s so boring. As an artist, I say fuck that debate. Let’s be done with it.

It’s not my job to please people who can’t tolerate anything but lukewarm baths.

The notion of likeability is a concern that the book industry has because there are people who read to feel nothing — people who read in order to check out. They don’t want to be disturbed by the words that they’re reading. They’re scared. The moment they feel challenged, they put down the book and review it on Amazon, “I just couldn’t get into this; it was too dark.” So when you’re selling a book and you say, this might have an effect on you, it turns off cowardly readers. I’m not concerned with those readers. It’s not my job to please people who can’t tolerate anything but lukewarm baths.

I read because I want to change, because I want to learn something and have an experience. If I’m having an experience where nothing is happening to me, I’m going to look at that book as… nothing. And I don’t want to write nothing.

MM: Eileen is obsessed with her body. Where did that interest in the body come from, and how did it evolve as you wrote this book?

OM: Eileen’s body is, in a way, her lover. It is the thing she knows the most intimately, and her relationship with her body is a way to engage with the world. Where it’s not safe to, let’s say, act out against her superiors at work, what she can do is objectify herself, and act out against her own body, as a way of processing her feelings.

I think that’s one way that eating disorders manifest. Or any kind of self-destructive tendency, like cutting. As a writer, it seemed implausible to me that Eileen could have a healthy relationship with her body given her circumstances.

Women are objectified so much that it was impossible for me to conceive of a book where that wasn’t an issue. And especially in this book, which is set in the early 60s.

MM: Is that interest in uninhibited and self-destructive behavior part of why you are interested in writing about drinking and drinkers? This shows up in McGlue as well as Eileen.

OM: I am interested in the ways that people cope with life. Alcoholism itself is not very interesting to me. If your identity as a character is that you are an alcoholic, it’s not going to be a very round character for me, in my writing.

That’s why the father in Eileen — that is who he is, he’s drunk and delusional, he makes messes — but he isn’t a whole person. He’s more like a ghost.

Drinking and doing drugs feed delusion. I’m interested in the stories we tell ourselves, and how they may conflict with other people’s stories about the world, and how, if we’re operating under a delusion, we might make really weird decisions. I like to explore that in fiction — why we do weird things.

MM: You chose to leave Eileen’s father as not a totally full character. Can you talk about that decision?

OM: On the one hand, Eileen as a grown woman has spent a lot of time coming to terms with the way that she feels about her dad, so I didn’t want the book to be, “Here’s me, Eileen, processing my feelings about my abusive alcoholic father.” I wanted the book to be more about Eileen extricating herself from that situation, and leaving behind this identity in search of a new one.

MM: One of your short stories in The Paris Review, “Disgust,” is a favorite of mine, and I wonder if we can trace a line from “Disgust” to Eileen. In “Disgust,” one of the major concerns was embarrassment and humiliation. And in Eileen, those are major ways in which the main character experiences the world. What makes embarrassment and humiliation literary subjects for you?

OM: They take the interior to the exterior. Humiliation is when people see a weakness in us, and we’re caught, exposed in that small moment. We’re vulnerable, and we’re received with judgment. That, to me, is a huge part of being alive — this negotiation between, who is it safe to expose myself to, and how does my fear of judgment limit me from being myself?

I also enjoy thinking about how funny it is that we care so much about the exterior: she has this haircut; he has that haircut; what does that mean — when really we all use the toilet? We all fart in our sleep. We all get pimples. We’re all mortal.

Yet we try to present ourselves in a way that is free from those bodily associations.

There is very good reason for that — people are afraid of death.

And for some people the exterior can become a complete obsession, the way that they create their outward identity. Either the inward disappears — and we call these people shallow — or it becomes so stifled that they become self-loathing or self-obsessed. That stuff is really interesting to me.

Spending time in New York, I’m overwhelmed by the obsessive image-making, and I mostly find it really fun to watch.

MM: This is a book about a bizarre murder. I was surprised by that, because in your short stories, the transgressions are much smaller. What drew you to write about murder, especially in the larger scope of the novel?

So maybe that’s part of my association with a novel: that it is a life and death situation.

OM: Maybe it was the conceit that because the novel is bigger, the transgression needs to be bigger. That happened with my first book, McGlue, too. It starts off with a murder, and in that case, I didn’t know that I was writing a whole book. I just knew that I needed to write that story. And it turned out that there was so much about that murder that it needed to be a book. So maybe that’s part of my association with a novel: that it is a life and death situation.

My attitude toward novel-writing is also very different from my attitude toward short story writing, and my interests in each form are different. Weirdly, a lot more subtlety can be explored in a short story, even though there is less room. Novels for me need broader strokes, so it seems natural that there would be bigger issues to deal with, in terms of storyline, plot, character behavior.

MM: The structure of Eileen is remarkable. There’s attentive observation of the mundane for a lot of the book, and then there’s an explosion of horrifying events. What made you want to structure it in that way, where you are beginning, very consciously, so far from the end?

OM: I wanted to create the feeling of Eileen being stifled and suffocated. I wanted the reader to feel suffocated like Eileen is, living in X-ville. So when Rebecca appears, it really is a lifeline, and things happen quickly thereafter. Eileen is so ready for those things to happen that there isn’t much more room to self-obsess. There isn’t a need for any more world-building, that work is already done. So we can just push forward.

MM: I was struck by lines like, “Nothing special happened that night…,” lines which draw our attention to the artifice of storytelling. What made you want to have that conscious presence in the book as a storyteller?

OM: Eileen, as the older narrator, is telling a story of these days in her past. There is no question that this is a construction. This novel has been written. It’s not like the Ten Commandments or something. We know a human being has put effort into the writing, and it was actually me! Hahaha.

But, I didn’t want the reader to forget that this was a character talking to them, and not an expert storyteller either. Eileen as a narrator cares that she’s understood, and there’s a lot of contradiction, and a lot of self-acceptance in that.

But I wanted her to feel alive as the narrator, so those interjections and little corrections are a way of keeping the reader aware of her.

MM: Let’s talk about the name of the town in the book — X-ville. What is interesting or necessary about that name to you?

OM: A name should be evocative. It is both the label of a place, and a word denoting the shared associations between people who know that place. When I say, Broadway, we both know what we’re talking about, and yet we must have different experiences of it. Names are proper nouns, not subjective. In that, they sit in the imagination with a lot of weight.

X-ville had to be X-ville because naming the actual town would’ve been too painful, and maybe too risky for Eileen. It was a way of distancing the entire story from her heart: I’m telling you this is a real place but I’m not going to tell you what it’s really called. In that way there is a gap between reality and story.

MM: Where is your own name from?

OM: My name is Persian. My dad is from Iran.

MM: What are your thoughts on other, recent feminist novels — Elena Ferrante’s Days of Abandonment, Claire Messud’s The Woman Upstairs. In those, there is a minute examination of domestic life. And in Eileen, domesticity is kind of a farce, but it’s also something Eileen wants. How do you think Eileen might be in conversation with those other books?

OM: I get angry thinking about Claire Messud’s book, and the hoopla around having this character who was a woman who was a little angry.

I didn’t think the opening rant in the book came across as being very hostile at all. Just because it was a woman writing it and speaking it, people were like: Oh my god, how uncouth! How experimental! Wake up, people.

In terms of domesticity, the world that Eileen knew was her house, this small town, and the prison where she worked. That was kind of it for her.

What does domesticity mean? It means, life at home. I don’t think of Eileen as a domestic character at all. The fact that she lives in a house makes her domestic, but no more than a cockroach.

MM: What does the practice of writing look like for you? Do you write by hand?

OM: I write straight on the computer. When I’m editing a novel, I’ll print out the draft and edit on paper, cutting things and taping them back together, stuff like that.

The process is really different depending on whether it’s a short story, novella, or novel. This novel I drafted very quickly, in 6 weeks, and then spent 10 months revising and re-writing. I don’t usually take a year to write a short story, but in some cases I do.

MM: Do you anticipate being edited? Has being edited changed how you write?

OM: What I like most about being edited is the perspective shift. I like looking at a piece as an object, rather than carrying the baggage of the process of writing, to my reading of it. Seeing it through an editor’s lens is refreshing and clarifying.

MM: Is there something you dislike, or that stays difficult, about writing and editing?

OM: No. It’s a joy. Writing is so much fun for me. What’s painful about writing is the fear that I can’t realize what I’m envisioning. But even that fear is a delight. I can’t tell you how much I love writing, revising, editing. It’s a complete fantasy. (laughs)

MM: Are there things you do that are not writing that you find are good for your writing?

OM: Yeah. Sleeping is really good for my writing. Dreaming. Walking. Seeing art. Listening to music. Seeing people I haven’t seen in a long time — it stimulates my memory. High risk situations are good. Travel is the big one.

Recently I wrote a story that was inspired by a really strange couple of days that I spent in this small coastal town in Kenya. The actual story doesn’t take place there, but it inspired the world that the story does take place in.

MM: Have you read anything good recently?

OM: I go through phases where I read a lot, and then I don’t read at all. I brought Volume 1 of My Struggle with me, and I just don’t know why I’m supposed to care about this self-obsessed, white European man. Why is he supposed to be interesting to me? I don’t find him interesting. Even when he’s being charming and funny, I don’t care. I don’t think I’m going to finish it.

MM: I read half of that book.

OM: Why did you stop?

MM: I felt that I knew what his writing was like, and that satisfied me.

OM: Same experience.

MM: What are you working on? What can we expect to read next?

OM: I have two novels that I’m working on, and I’m writing personal, narrative essays. Or, I wrote one. Now I’m writing another.

MM: That was the one about mayonnaise.

OM: Yeah. Now I’m writing about birds that I’ve known, personally.

MM: What draws you to non-fiction?

OM: I’m at a place in my life where I’m old enough to have perspective on my childhood. All of a sudden, I’m not a child. I don’t know how that happened.

I come from a fascinating family of very special people with endless good stories. There’s so much to explore there, and funneling it through fiction is less interesting for me right now. Why not just say what really happened?