Reading Lists

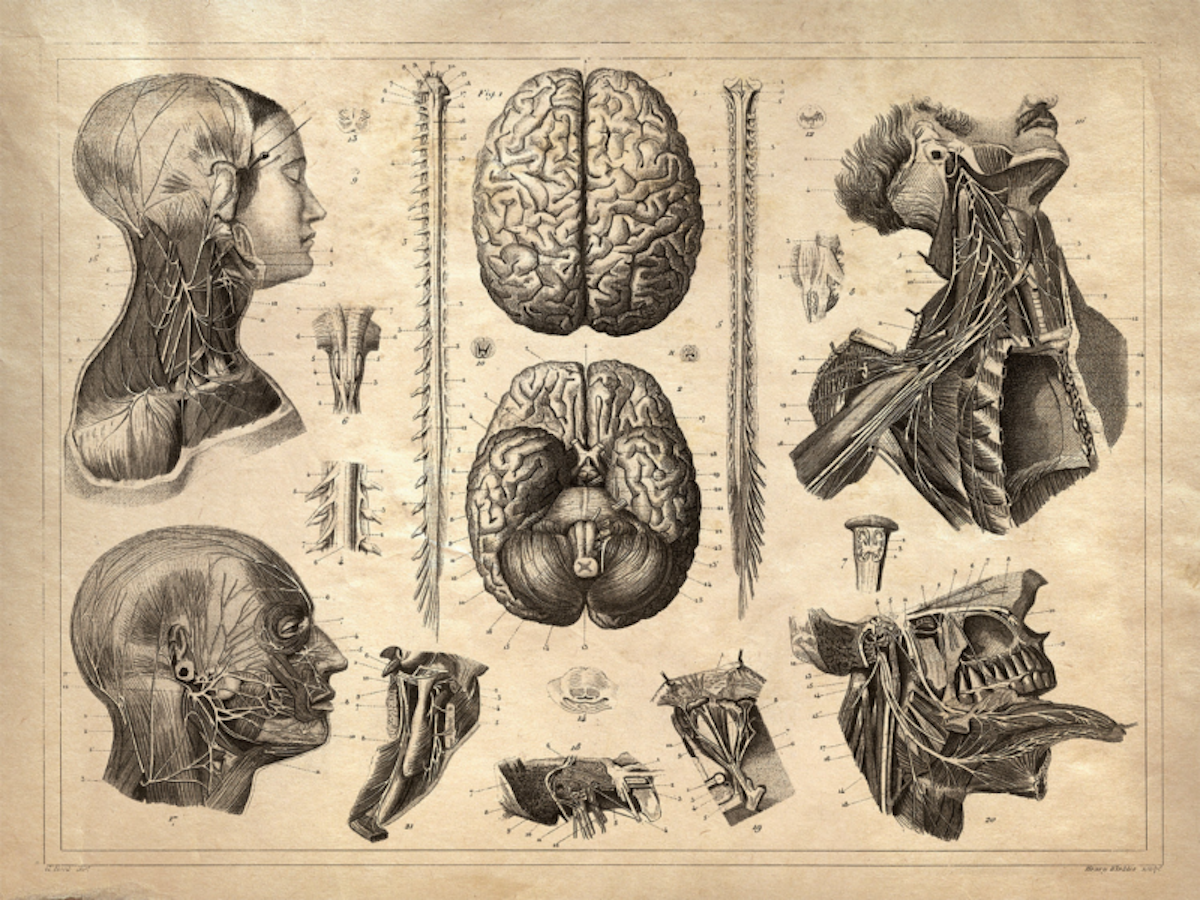

12 Great Books About the Human Brain

Author Jason Tougaw examines the growing trend of novels and memoirs that take on the ‘hard problem’ of human consciousness

I n 2009, Marco Roth started a minor controversy by declaring in N+1 that the so-called “neuronovel”—the novel that deals in detail with the workings or malfunctions of the brain—was “another sign of the novel’s diminishing purview.” By Roth’s account, “the rise of the neuronovel” signaled the death of the novel. His primary target was Ian McEwan, specifically his novels Saturday and Enduring Love, both of which offer neurological explanations for psychological behavior and social circumstances. Roth’s list of neuronovelists also includes Jonathan Lethem (Motherless Brooklyn), Rivka Galchen (Atmospheric Disturbances), and John Wray (Lowboy).

Roth argues that these novelists are capitulating to deterministic biological accounts that reduce the complexity of life to mere physiology. That’s where I think he got the story wrong. These writers don’t reduce life to biology. They play with biology to experiment with literary form; they include physiology as a category of human experience, and they explore the mysteries inherent in the fact that we are physical creatures whose brains play unknown roles in the making of our fantasy lives, our sense of self, our feelings, our identities, and consciousness. Even McEwan’s Henry Perowne, the hyper-rationalist neurosurgeon who narrates Saturday, wonders “that mere wet stuff can make this bright inward cinema of thought, of sight and sound and touch bound into a vivid illusion of an instantaneous present, with a self, another brightly wrought illusion, hovering like a ghost at its centre.” Philosophers and neuroscientists call this “the hard problem” — figuring out how the wet stuff might make consciousness.

I might not agree with Roth, but he coined a great term — neuronovel — and recognized a genre on the rise. Simultaneously, a genre I’ll call the brain memoir — an autobiography in which the brain’s role in the making of identity is central — has also been flourishing. Dozens and dozens of neuronovels and brain memoirs have been published in the last couple of decades. These are some of my favorites.

I should admit: I’m biased. I’ve published a brain memoir, and I’m publishing a book about the “rise” of both genres next spring. But anyone, even those who don’t have a stake, can enjoy these books about the human brain.

1. Tito Rajarshi Mukhopadhyay, How Can I Talk If My Lips Don’t Move?: Inside My Autistic Mind

Mukhopadhyay was sixteen when he published his first book of poetry and nineteen when he published his memoir. Publishing a book at age sixteen is a remarkable achievement, but that’s not the primary reason age matters when it comes to Mukhopadhyay’s books. His youth is significant because it represents the development of the culture’s response to autism. Mukhopadyhay has become a spokesperson for neurodiversity — the idea that there is value in the neurological differences between one person and another. He’s a profoundly social writer, inviting readers to get intimate with the way his mind works. Not so long ago, it was widely believed that autistic people, particularly non-verbal ones like Mukhopadhyay, couldn’t communicate at all. Mukhopadhyay’s lyrical, sure-toned writing is one of many recent memoirs that force us to rethink brutal history of autism and imagine a more just and compassionate future.

2. Siri Hustvedt, The Blazing World

In The Blazing World, Hustvedt tells the story of Harriet Burden (Harry for short), an artist who takes elaborate revenge on the sexist art world by borrowing the bodies and identities of three different male artists — and disseminating her work under their names. As one of the novel’s narrators describes Burden, “The woman was chin-deep in the neuroscience of perception, and for some reason those unreadable papers with their abstracts and discussions justified her second life as a scam artist.” Harriet is interested in making art that elicits discomforting and eccentric neurological experiences. Hustvedt emphasizes Burden’s didactic mission. She conceives her exhibitions quite literally as laboratories. She wants her audiences to feel, in a visceral sense, the fundamental relationality involved in being an organism — a relationality that entwines biology, identity, social life, and culture.

3. Thomas DeQuincey, Confessions of an English Opium Eater

In his famous Confessions, DeQuincey delights and despairs in opium’s effects. “A theatre seemed suddenly opened up and lighted in my brain,” he writes. He recognizes his visions as the product of brain chemistry, but sometimes feels certain they are remaking “objective” reality — the one we share — in the image of his fantasies. In his preface, DeQuincey worries that his “moral ulcers and scars” will be revolting to an upright English audience, who wince at “the spectacle of a human being obtruding.” He needn’t have worried. His obtrusions made him a literary celebrity. Some things haven’t changed.

4. Kay Redfield Jamison, An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness

In An Unquiet Mind: A Memoir of Moods and Madness, Kay Redfield Jamison stresses a problem with writing about her bipolar disorder central to any memoir about neurological difference: “I have become fundamentally and deeply skeptical that anyone who does not have this illness can truly understand it.” Jamison’s professional identity — as a research psychologist and a writer — is linked fundamentally to her illness. The difficulty she describes, “weaving” the disciplinary methods of science with her emotional experience is cultural more than intellectual. Throughout her memoir, Jamison demonstrates the many ways the symptoms of mania allow her to approach her research and writing with imagination and energy.

5. Ellen Forney, Marbles

Ellen Forney’s Marbles: Mania, Depression, Michelangelo and Me tells the story of its author’s evolving identity in response to a bipolar diagnosis. Marbles portray its characters’ brains as part of an ensemble of images that define their search for what it means to suffer as a result of neurological conditions beyond their control. Forney is explicit about her urgent need for knowledge about the brain as well as her awareness that this knowledge can only be hypothetical and contingent. Forney offers a vivid example of her chosen form’s capacity to transform ideas through images, with her depiction of a page from the DSM as a dreamlike carousel, a pictorial metaphor designed to encompass her ambivalence about her bipolar diagnosis. Forney uses the carousel to parody the DSM’s linear list of bipolar symptoms. On her carousel, depression curls up under a pony; “mixed states” tears the pony in two, clinging to its upper torso and balancing precariously on its back; mania stands on the pony with a single foot, her head bumping against the merry-go-round’s ceiling.

6. Miguel de Cervantes, Don Quixote

People — or critics like Harold Bloom — like to say Don Quixote is the first modern novel. If so, it may also be the first neuronovel. As Sancho Panza narrates the story of his squire’s antic wandering, he attributes his deranged fantasies to two related sources. He has read too many books. As a result, his brain is “dried up,” “cracked or broken,” “full of wind.” At one point, the nobleman from La Mancha tells Panza his “brain is melting.” In the original Spanish, the word is cabeza, meaning both head and brain, but also the brain as an abstract concept, as opposed to the actual organ inside the head. Like all the best neuronovels, Cervantes plays around with the relation between that physical organ and the immaterial experiences of mind and self.

7. Kazuo Ishiguro, The Unconsoled

Ishiguro has told interviewers that his most audacious novel — people love it or hate it — is an experiment with writing in “the language of dream.” Each section begins with Ryder, the novel’s bewildered narrator, waking up from sleep he can never get enough of, and finding himself in a world where closet doors lead to art parties, where strangers turn out to be his wife and child, and where there’s a city full of people who are certain his opinions about aesthetics will save them. It’s an experiment in disorientation, and I guess that’s why so many readers find it frustrating. But to me it’s a page-turner. If I pick it up, I can’t put it down. Ishiguro is a master.

8. Paul Beatty, The Sellout

Beatty’s narrator tells his hilarious LA story about reviving both racial segregation and slavery from inside the Supreme Court, while he smokes outlandish amounts of artisanal weed he’s been growing, along with watermelons, back in LA. This is a story told by a guy who’s incredibly high, a guy experimenting with his brain chemistry while he addresses the most sober institution in the United States. It’s also a story told by a guy whose father was a fairly unhinged academic who conducted psychological studies on him, starting at an early age. The narrator’s father is like Dr. Frankenstein or Jean-Jacques Rousseau with his creepy fantasy about raising the perfect little girl. He experimented on his son to explore some hazy theories about the construction of race and the internalization of racism. Beatty turns the hard problem into social satire about the racism that plagues American culture.

9. Richard Powers, The Echo Maker

The Echo Maker tells a story about a man with a rare neurological syndrome called Capgras Syndrome, embedded in another about a breed of crane whose nesting habitat is threatened by real estate development. As a result of brain injury sustained in a car accident, Mark Schluter awakens with the delusional belief that his intimates — especially his sister Karin—are impostors. It features a character based on Oliver Sacks, a neurologist famous for turning his patients into stories. Power’s lyricism is key to understanding his novelistic response to neuroscience. Powers begins the novel not with the accident, the coma, or the awakening, but with a lyrical description of cranes returning to the small Midwestern town where the Schluters were raised, a passage that begins with a “sky, ice blue,” that “flares up, a brief rose” as the “nervous birds, tall as children, crowd together” on a river “they’ve learned to fly by memory.” When Mark finally speaks, his sister asks his neurosurgeon a crucial question about the combination of his echolalia and disorderly speech. Does the apparent nonsense mean anything? “Ah! You’re pushing up against questions neurology can’t answer yet,” he replies. And that’s where literature comes in. Powers opens his novel with a lyricism that depends on the interplay of words to create novel meanings, to transform skies into roses and cranes into human children. Literary language, he seems to be suggesting, shares with Mark’s echolalia a capacity to blur the boundaries between sense and nonsense — or to create speculative knowledge that works as much through feeling as it does through thought.

10. David B., Epileptic

In David B.’s graphic memoir Epileptic, he portrays an impossible fantasy: that he might find a doctor who could “transfer” his brother Jean-Christophe’s epilepsy into him. He fantasizes that an exchange of brain matter might enable him to feel what it’s like to be his brother. “I fantasize,” David B. writes, “that I could take on my brother’s disease if a resourceful scientist were to transfer it into my skull.” It’s a fantasy of overcoming the explanatory gap, a term coined by philosopher Phillip Levine to describe a persistent obstacle to understanding consciousness from a neurobiological point of view: nobody can explain how immaterial experience — self, consciousness, cognition, memory, imagination, affect — emerges from brain physiology. Throughout Epileptic, he struggles to empathize with Jean-Christophe. In his fantasy, brain science will rewrite his failure and undo the mutual alienation of two siblings. But no scientist is that resourceful.

11. Thomas Harris, Hannibal

Harris’s Clarice Starling hunts Hannibal, the brilliant psychopath, only to become his willing abductee (though at novel’s end readers are primed for a sequel that will unravel the plot of its gothic melodrama). Harris wrote four Hannibal books, two of them adapted into films starring Hopkins. While Silence of the Lambs (1991) was the more critically successful of the two films, the brain-eating scene in Hannibal (1999) is legendary. Both books were international bestsellers, but their details tend to be obscured by the notoriety of the films. As a novel, Hannibal is not well remembered for its pervasive discussion of theories about the mind and memory. Lecter fancies himself an expert on human minds, both a theorist and a practitioner, one who believes he alone possesses the keys to the brain: “The memory palace was a mnemonic system well known to ancient scholars and much information was preserved in them through the Dark Ages while Vandals burned the books. Like scholars before him, Dr. Lecter stores an enormous amount of information keyed to objects in his thousand rooms, but unlike the ancients, Dr. Lecter has a second purpose for his palace; sometimes he lives there.” In the novel’s most famous scene, Hannibal feeds a drugged Starling the brain of her professional rival, with the intent to control her mind.

12. Christopher Isherwood, A Single Man

Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man (1964) is an early neuronovel — and a particularly prescient and sophisticated one. Its protagonist, George, is a professor grieving for his lost partner, Jim. His grieving is solitary. The homophobia of his world curtails communal mourning rituals. In response, he narrates himself in ecological terms, as an organism, his brain and body commingling with an environment fundamentally changed by the loss of his most intimate companion. George wrestles with his brain throughout the novel. He worries that his students see him as “a severed head carried into the classroom to lecture to them from a dish.” He laments that they “don’t want to know about my feelings or my glands or anything below the neck.” As he tries to sleep, “the brain inside the skull on the pillow cognizes darkly” — enabling him to consider “decisions not quite made,” decisions “waking George” can’t face. When he sleeps, “All over this quietly pulsating vehicle the skeleton crew make their tiny adjustments. As for what goes on topside, they know nothing of this but danger signals, false alarms mostly: red lights flashed from the panicky brain stem, curtly contradicted by green all clears from the level-headed cortex. But now the controls are on automatic. The cortex is drowsing; the brain stem registers only an occasional nightmare.”

About the Author

Jason Tougaw is the author of The One You Get: Portrait of a Family Organism (Dzanc Books). Portions of this list are excerpted from his forthcoming book The Elusive Brain: Literary Experiments in the Age of Neuroscience (Yale University Press). Tougaw blogs about art and science at californica.net.