essays

31 Fairly Obscure Literary Monsters

Halloween used to belong to the monsters. Tracing a perfect near-continuum from the Frankenstein’s Monsters and Gill-Men that papered many a boyhood bedroom to the disturbed teenager’s diet of Lovecraftian doom and the unlaid English major’s repository of Victorian dreadfuls, the creatures of the night once held a monopoly on populist hair-raising. But in the hallowed eves of today, you’re more likely to see the harbingers of nostalgia — the likes of Urkel, Carmen Sandiego and drag Monica Lewinsky — than the emissaries of the undead, the restless hunger for immortality, lycanthropy, and Modern Prometheum seemingly slaked by Sexy Corn, rock star wish-fulfillment and an endless contest to achieve the slyest wordplay couple costumes (last year’s winner: Baroque-en Record and Edwardian Scissorhands) or tastelessly topical shock valets (I don’t mean you Binders-Full-Of-Women, I mean you, Zombie JonBenet Ramsey). When did the stop-motion lizard people of the late-night circuit, the high gothic of Mary Shelly and Siouxsie Sioux, become passé and what is to be done when Bela Lugosi is forced to take a backseat to SpongeBob and Shrek? And who will haunt the suburban thoroughfares and laborsome loft parties when we are gone? For those of us that borrowed our friends’ cars to see the midnight showing of The Hunger and maintained a preference for muppets over CGI, monsters weren’t a fad, but a lifestyle. Assigned Ayn Rand and A Separate Peace, we snuck away to read Anne Rice, I Am Legend,and Poppy Z. Brite. Once the moon was full enough to cover every one of us; adolescent America was one big Midnight Society gathered around the campfire and we all had hooks for hands.

Fortunately, literature — even as compared to movies and bartender tattoos — isn’t just full of monsters, literature is monsters. Admittedly, the most memorable killers have come in human(ish) form, from Blaise Cendrars’ Rippers-eque Moravagine to sign-of-the-time slashers like Patrick Bateman and Hannibal Lector. But that’s not to say that books aren’t rich with waking nightmares, undigested psychological ectoplasms and tentacles in general. The following list aims to undo the long influence of irony with its evil twin and opposite number: deliberate obscurity and humorless elitism. All vampires, Gorgons, flesh-eating cadavers, Kaiju and denizens of the Monstrous Manual have been scrupulously excised. This, if you dare, are the well-nigh forgotten monsters of classic literature, because the idle past is always preferable to the overfamiliar present, and true monsters are not just the embodiment of period anxieties, but the horrific realization of the future. For that is where you and I are going to spend the rest of our lives.

The Sandman From “The Sandman” by E.T.A. Hoffmann (1816)

It would be remiss not to begin with the monster that gave Freud his principle instance of “the uncanny.” Hoffmann’s traumatized hero begins by recalling the legend of the Sandman, who steals the eyeballs of children as they wake in fright and goes on to see the Sandman everywhere; in his own memories of his father’s unsavory friend Copellius, a “borometer-seller” named Coppola and lurking somewhere behind his own eyes. Grand Guignol subplots proliferate (including the love of a clockwork woman), but in the end Hoffmann dares us to look inward, to the origin of our desires where dreams mingle with half-recalled memories and where there is no guarantee that such clarity won’t mean madness and suicide. Such is the price for seeing too much.

Gil-Martin From The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner by James Hogg (1824)

A distinctly Red State boogieman despite being the creation of a Scotsman, Gil-Martin is the otherworldy and inseparable companion — something of a homicidally misanthropic Socrates — of the religious zealot Wringhim. Gil-Martin assures his friend that there can be no sin when one is chosen by God and much of Wringham’s confession is given over to Gil-Martin’s sophistry: “What is the life of a man more than the life of a lamb, or any guilty animal? (…) Can there be any doubt that it is the duty of one consecrated God, to cut off such a mildew?” Convinced that he murders in God’s name, Wringhim terrorizes his would-be congregation only to slip deeper into Gil-Martin’s power. Unlike most monsters, more likely to eat your heart than discuss the correct interpretation of scripture, Gil-Martin is an intelligent fiend and one of the most convincing depictions of pure evil in all literature. Toward the end of the novel, the Wringhim’s charismatic councilor is accused of being the devil — but the canny reader will recognize Rousseau, whose approach Hogg loosely parodies.

The Man of the Crowd From “The Man of the Crowd” by Edgar Allan Poe (1840)

If you live in a metropolitan area, you’ve probably caught yourself occasionally thinking of people less as individuals with distinct selves than as the tendrils of the vast and unfathomable crowd. But what if this were literally true? What if some of the people you pass on your commute had no existence separate from their abeyance to the city’s inscrutable rhythm? So it is with the ragged and weirdly featureless old man that our narrator follows through the city, a criminal without a crime, a living blank of a human being onto which the crowd seems to project its random desires on a loop. Far scarier than Poe’s usual neurasthenic murderers, “The Man of the Crowd” is also one of the strangest things he ever wrote (including his many comedies and “The Philosophy of Furniture”). Like the Man of the Crowd himself, the story is an enigmatic dead level unaccentuated by any plot or obvious intent.

Beatrice Rappaccini “Rappaccini’s Daughter” by Nathaniel Hawthorne (1844)

What is it about Beatrices? The latest in a long line of awestruck young men falling into a personal hell for the sake of a Beatrice, our hero is distracted from his studies by his view of the lustrous garden of mad botanist Giacomo Rappacini, who has raised his daughter to tend his poisonous buds and assorted ivies (note the lingering sense of Italians as exotic evildoers). Technically more proficient than a lot of the stories on this list, it’s still a challenge to not make “Rappaccini’s Daughter,” sound insipid; suffice to say, Beatrice builds up a resistance but, in the bargain, becomes pure poisonous love whose kiss is death. Disaster ensues. If there’s one thing that’s more amazing about Hawthorne’s story than that it out-Poes Poe, is more of a page-turner than Henry James’ more ambient “Turn of the Screw” or that his gift for description is seemingly without limit, it’s how much Beatrice, swathed in the metaphor of thorny roses and so on, seems to anticipate the invention of the rock ballad.

Silas Ruthyn From Uncle Silas by J. Sheridan Le Fanu (1864)

A dead-on Victorian novel with all the trimmings, Uncle Silas is effectively a re-do of Charlotte Bronte’s painfully anticlimactic Villette, featuring the titular cadaverous, opium-addicted, possibly-vampiric Third Uncle, who torments an ingénue before trying to marry her off to his idiot son (like Leatherface, but with a claw hammer instead of a chainsaw). One of the great villains of the era of triple-decker novels, Uncle Silas also gave the Peter O’Toole the most scenery-eating role of his career, in the BBC movie adaptation Dark Angel.

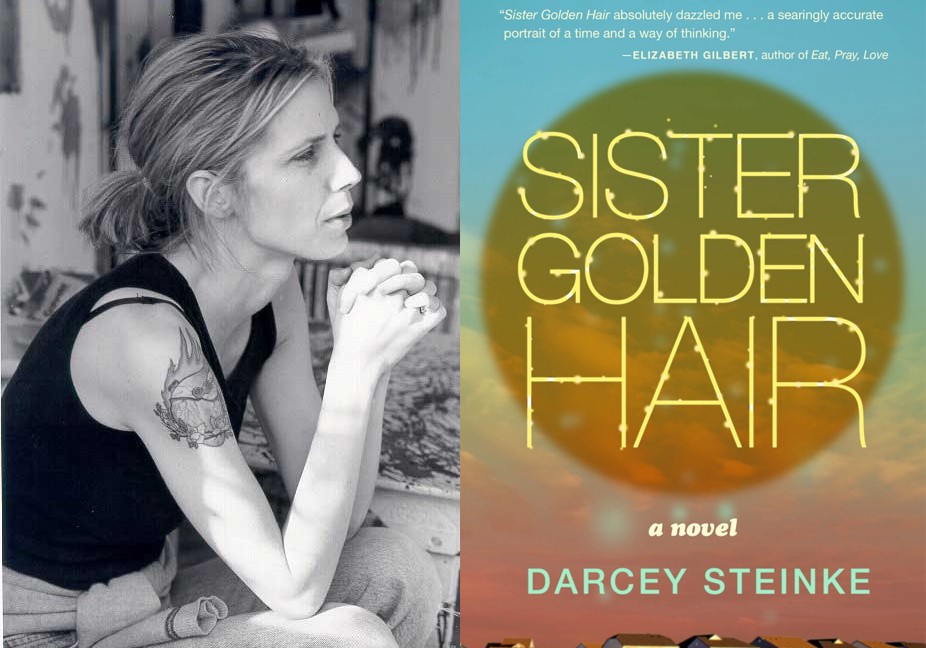

Lokis From “Lokis” by Proser Mérimée (1869)

Although Proser Mérimée is best known as the author of Carmen, if “Lokis” is any indication, his heart was really in tales of rapey Lithuanian Were-bears. Clawing his way out of the birth canal, Michel tries to repress his beasty nature. But the pressure of marriage proves too much, despite his efforts to keep it together, “Lokis” breaks out and his honeymoon turns into a bloodbath, after which he disappears into the forest to eat salmon, shit, trundle, hibernate and break into horseless carriages for the rest of his days.

The Horla From “The Horla” by Guy de Maupassant (1887)

The most frightening monster is that which is indistinguishable from madness. In this, the greatest of Maupassant’s many ghost stories, a pampered bourgeois becomes possessed by a parasitic consciousness that, among other trespasses, leads him to abuse his servants and burn down his house. A parable for class privilege and the self-destructive violence of the late Nineteenth Century’s landed gentry? Sure, but the suffering of our narrator and his struggle to find where he ends and the Horla (a sort of mental Mr. Hyde) makes “The Horla” the pinnacle of psychological horror and the appeal of bodily-displaced “mind vampires” has never really faded, from Freddy Kruegar and Killer BOB to the atemporal Horologists of David Mitchell’s recent The Bone Clocks.

Ayesha From She and Ayesha and others by H. Rider Haggard (1887)

One of the best-selling novels in history, She is pure colonial fantasy in which a pair of gentleman adventurers discover a primitive civilization presided over by She-Who-Must-Be-Obeyed, an immortal queen of a pre-Egyptian kingdom consecrated by fire and hands down my favorite mummy. Even if everything that surrounds SWMBO (or “Ayesha,” to the re-incarnated lovers she lures to her den) reads as faintly dumb or familiar by modern standards, Ayesha is an amazing character and, unlike most female monsters of the period, is depicted as formidable, self-possessed and eloquent even if desire does proves to be her undoing…at least until the sequels, which kept coming and inspired an entire genre of ‘lost city’ novels, Tolkien’s elf-queen Galadriel and a Hammer Horror film starring Ursula Andress.

The Damned Thing From “The Damned Thing” by Ambrose Bierce (1893)

Ur-American horror writer Ambrose Bierce is back in public consciousness thanks to True Detective — but if you found the actual Carcosa less frightening than your anticipations, you’re in luck. The Damned Thing is not a redneck child murderer, demon from hell or, despite the claw marks left on its victims, a mountain lion. It’s just some kind of thing. According to Bierce it’s a color we can’t see inhabiting an imperceptible air-inside-the-air. The point is, whatever it is, it hates us and it is everywhere all at once. Of course this Thing is only the granddaddy of all Things, from Lovecraft’s indescribable Things (which, nonetheless, he never tired of describing) to John Carpenter’s Thing, which not a dog in the same sense that The Damned Thing is not a mountain lion. As monsters go, Things have one big advantage over the human race: we can only describe what they aren’t. In other words, you won’t know it when you don’t see it.

The Great God Pan From “The Great God Pan” by Arthur Machen (1894)

Welsh freakazoid Arthur Machen’s grotesque novella about pagan orgies and brain surgery was just part of the prevailing fashion for Goat Gods — which were as ubiquitous in fin-de-siècle as zombies today — but he almost definitely invented the concept of tripping your balls off. Beginning with a scientist who wants to open the human mind to better understanding through creative lobotomy, he inadvertently opens the doors to Pan the pleasure god. What follows is an engagingly anarchic narrative (I use the term loosely) of rape, suicide and shape shifting women. Machen was a devoted occultist and late convert to Celtic Christianity and the tension between antiquity and modernity, what can be known and what lives just beyond comprehension, is present in all of his fiction; but not even his fae “White People” can equal Pan for sheer goat-fucking insanity.

Morlocks From The Time Machine by H.G. Wells (1895)

Whereas most science-fiction stumbles by leaping ten or twenty years into post-apocalypse, the more optimistic Wells’ sets his after-scape in the 8,028th, just to be safe. Because, who’s to say that the inheritors of the planet won’t be subterranean albino ape-men? The Morlocks are not just literature’s premier subway-dwelling mutants, they remain its most malevolent, an evolutionary step backwards toiling in the pure night of a post-electric world, emerging from their tunnels to feast on the flesh of the Eloi (basically Californians to the Morlocks’ New York).

Sredni Vashtar From “Sredni Vashtar” by Saki (c. 1901–1911)

A blood-drinking polecat worshipped by a psychotic ten-year old boy. Devourer of cousins. Anyone looking for a pet name?

Count Magnus From “Count Magnus” by M.R. James (1904)

In M.R. James’ genre-establishing weird tale, a travel writer in darkest Sweden fails to appreciate a series of painting depicting the Count Magnus de la Gardie and ventures into the Count’s mausoleum only to encounter…something (the journal breaks off and we go back to the frame story). As ghost stories go, this may not sound too scary, but just imagine if the last piece of art you failed to fully appreciate decided to kill you.

Alraune From Alraune by Hanns Heinz Ewers (1911)

Next time you need to name check a novel about a prostitute impregnated with the sperm of a hanged man by a mad geneticist so that she gives birth to a vengeful nymphomaniac written by a homosexual Nazi, you’ll be glad we had this chat. There’s not a lot more to say, except this once-wildly popular answer to Frankenstein (of which it is kind of a misogynist reworking) is, I’m afraid, partly responsible for the Species movies. The more things change…

Thak, the Man-Ape From “Rogues in the House” by Robert E. Howard (1934)

Simian overlords and deadly orangutans are certainly not underrepresented in fiction, but if you’re talking about giant things beating the shit out of each other, you’re talking about Conan the Barbarian. In the unusual and early installment of the Cimmerion’s adventures, Howard mimics the style John Webster in a convoluted story with an excellent end-boss: the usurper Thak, an intelligent ape who has replaced a powerful clergyman and plots to rule the surrounding cities as a theocrat. Do I have to say more? It’s fucking Thak! All hail Thak!

The Newts From War with the Newts by Karel Čapek (1936)

Karl Čapek’s unbelievably perceptive political fantasy War with the Newts centers around the titular Sumatran newt-people. Discovered just beyond the reefs of the known world, humanity quickly outsources its labor to the aquatic Newts. Only when mankind has become completely dependent on the new, hydroengineering-based economy do the Newts begin demanding a bigger cut of the coastline, by which time even the most highly-developed nations are in no position to refuse. Despite the title, the war isn’t a war so much as a massacre, as frogman proves himself by far the more adaptable species. Čapek’s targets are complex: nationalism, racism and, above all, capital — but the Newts are more than the means to a sociological end, as they evolve from gentle pearl-divers to an indignant proletarian class and finally take their place as the new master race.

It From “It!” by Theodore Sturgeon (1940)

Sturgeon is probably most famous for developing the useful Sturgeon’s Law — that is, “Ninety percent of [science fiction] is crud, but then, ninety percent of everything is crud.” — and the nameless swamp monster of “It!” is the embodiment of this philosophy; a creature of pure waste, sentient fungus and accumulated detritus that lumbers through the countryside contemplating Its own oppressive consciousness even as it absorbs more fungus, moss and rot into its membrane. Like the very best monsters (including Its direct descendants Man-Thing and Swamp-Thing), It exists in a state of in-between-ness, occupying the void between living and unloving, natural and unnatural.

Cassavius From Malpertius by Jean Ray (1943)

In this Belgian gothic-surrealist novel…sorry, I’ll start again; Cassavius is the ultimate realization of Belgian oddball Jean Ray’s twin interests in Cocteau-like fantasy and sublime strangeness reminiscent of Bruno Schultz or Paul Valéry. A well-traveled collector and warlock (Orson Welles in the otherwise memorable film version), Cassavius builds a sprawling mansion to house his collection, which happens to consist of figures from myth trapped in flesh and forced to roam the grounds reliving their Hellenic salad days. This is as good a place as any to mention that when I was 8, my best friend Robert Harris locked me in the garage until his mom came home. Actually, I am still there.

Tash From The Horse and His Boy and The Last Battle by C.S. Lewis (1954 and 1956)

We all know that heavy-handed theologian worked Jesus into his Chronicles of Narnia as the lion Aslan, but did you remember that Narnia has its very own anti-Christ? That would be Tash the giant vulture-skulled Demiurge. Originally, presented as a cultural, rather than religious deity — that is, a swear word more than an actual being — Tash turns out to be totally real in the more-grisly-than-you-remember Last Battle. Tash is the false God made real, the monster we make when when we serve our own interest in Heaven’s name. Or maybe Lewis is just a pedantic patriarchal family-values allegorist (see the more-stupid-than-you-remember Screwtape Letters).

The Howling Man From “The Howling Man” by Charles Beaumont (1959)

Although the Twilight Zone adaptation of the ridiculously prolific Beaumont’s short story will have you believe that the man locked up in the dungeon Benedictine castle and guarded by an order of monks is the Devil, he isn’t. He’s the 20th century and when a boarder, tormented by screams in the night, sets him free, he unleashes 100 years of genocide, iniquity and nuclear war. Anastasia screamed in vain.

The Plants From The Genocides by Thomas M. Disch (1965)

The premier work of science hick-tion takes us out of the futuristic cities of most space opera and into the hinterlands, where spherical aliens have seeded giant deadly trees throughout planet, overwhelming the natural flora, blocking the sky, oozing sap, and replacing the welkin with a toxic atmosphere. More menacing than a Triffid, less fun than an Ent, this evil crop turns out to be an elegant metaphor for the climate’s indifference to man. Disch’s tiny band of backwater types enact their petty jealousies and give way to infighting, but not before taking a sylvan journey into the heart of the Other, to the place where all roots entwine. The Plants are the monstrous monoculture at the center of the world, who are still not altogether of it.

Behemoth From The Master and Margarita by Mikhail Bulgakov (1967)

How does Behemoth manage to stick out in a kaleidoscopic Soviet masterpiece whose other characters include Pontius Pilate, assorted succubae, a demonic assassin and Satan himself? It might be because he is a demonic seven-foot cat that walks upright, plays chess, knocks back vodka with the devil and makes wisecracks that are either untranslatable or just proof that cat humor is wasted on me. Other than being a talking feline, the louche Behemoth wouldn’t be out of place in most grad programs: he is sarcastic, well-read (to the point that he’s even read manuscripts that were burned by their authors) and indebted to powerful and evil forces. There may be more sinister cats in fiction, but as Satan’s minion — or, rather, mascot — Behemoth combines the amorality of house pets with the blithe condescension of somebody who wants you to know he knows somebody very famous. Also, his name means hippopotamus in Russian, which is a pretty good name for a cat.

Knife-Wielding Death Dwarf From Daphne Du Maurier’s “Don’t Look Now” (1971)

Daphne Du Maurier’s fascinating horror story “Don’t Look Now” (the inspiration behind my favorite film of the same name) may be the only work of fiction entirely based on the dangers of misinterpreting metaphor. While a killer roams Venice, a vacationing couple mourning for their deceased daughter fall under the sway of a pair of identical twins and become fixated on a strange figure in a red raincoat — just like little Christine used to wear. But it isn’t their little girl, it is a terrifying dwarf with a razor; the premonitions we’ve been following were only premonitions of an absurd and meaningless death.

The Cupboard Man From “Conversation With A Cupboard Man” by Ian McEwan (1972)

Nothing to see here, just a masturbating homunculus who lives inside a cupboard.

He’s in yours right now.

Misquamacus The Manitou by Graham Masterton (1975)

Graham Masterton, the author of over two-dozen sex instruction booklets, has produced a baffling series of books probably aimed at making us forget the movie made out of his first, The Manitou. Misquamacus is an Indian spirit (more properly, a Manitou, a monster so Canadian-sounding, they named a Province after it) that takes possession of a fetus so as to exact vengeance on the white man; so far, so good but the problem is that Misquamacus doesn’t wait to grow up, but just goes for it after charging out of his mother-host’s uterus. A truly malevolent fetus, his rampage doesn’t get much farther than the nursery but deserves massive points for effort.

Freddy From Freddy’s Book by John Gardner (1980)

Freddy is the secret progeny of a University professor who keeps his enormous, ogre-like son secured in the attic, where, hidden from sight and denied any human contact, he wiles away his hours of captivity writing a book about Vikings. Freddy is, in other words, the writer we’d all like to be.

Larry the Lizard From Mrs. Caliban by Rachel Ingalis (1982)

Mrs. Caliban is a quiet, pensive domestic drama reminiscent of Evan S. Connell’s Mrs. Bridge or Chopin’s The Awakening with the distinction of featuring a giant lizard-person. Larry, having escaped from an experiment, falls in love with bottled-up housewife Mrs. Caliban and reawakens the passion that has been all that snuffed out by a loveless marriage and the loss of her son. Mrs. Caliban’s lizard may not seem very threatening as monsters go — indeed, he seems an affable gentlecreature and alert lover — but Ingalis’ tone is less magical than it is wistful; Larry may be a figment of Mrs. Caliban’s loneliness and repressed desire, which establishes Ingalis’ short novel as a deeply feminist text and Larry as belonging to the same class of inner-beasts-made-manifest as Lon Chaney’s Wolfman.

Mr. Hood From The Thief of Always by Clive Barker (1992)

Clive Barker is known for his vaguely kinky horror and fantasy novels, but The Thief of Always is a surprisingly durable fable about a jaded young boy with the adorably Dickensian name of Harvey Swick who is invited to the Holiday House — where every morning is Christmas and every night is Halloween — at the invitation of the mysterious Mr. Hood. His every childish whim attended to, Harvey is loath to return home; but when he does, he finds that years have passed, his parents have all but given up looking for him and Mr. Hood is the house itself, draining the years from the children he lures inside his doors.

The Thieving Bears of Thieving Bear Planet From “Thieving Bear Planet” by R.A. Lafferty (1992)

Actually, they’re more like large flying squirrels, but made mostly of fluff “with not much body inside it,” the better to hide the things they steal. The only known inhabitants of an otherwise worthless and uninteresting planet, the only given scientific reason for the bears’ existence is that “anomalies are necessary.” But woe to the spaceman who touches down even briefly on Thieving Bear Planet, for he will find himself denuded not only of all his Pepsin capsules and comic books, but — such is the cleverness of Ursus furtificus — he will soon lose even his knowledge of the cosmos beyond and, eventually, his ghost.

Mr. Potato Head From “Subsoil” by Nicholson Baker (1994)

Leave to a first-class observer of radical normality like Nicholson Baker to finally tap into the uncannyness of stem tubers. An agricultural historian Nyle T. Milner stays the night in a mysterious house well-stocked with vintage boargames, where he dares to play with an “original” Mr. Potato Head made from an actual potato (was this a thing?). The description of the potato’s vengeance is impossible not to quote: “A sprout grew smoothly into his right knee, seeking his synovial fluid. Several more penetrated his elbows. These hurt quite a lot, though not nearly as much as the one that found its way into his urethra. One wan ganglion discovered his ear canal, and another a tear duct, and Nyle began to hear only the dim, low pulsation of plant hormones and potato ideology.” In the night, the potato takes its vengeance, unfurling its roots to take possession of its victim and . Beware the potato, my friends, for the next fruit of the earth dug up for a child’s amusement may be your skull.

Kafka’s Father From Letter to His Father by Franz Kafka (First, Last and Always)

Franz Kafka’s Letter to His Father is the greatest work of introspection ever written and one of the holy grails of modernism, in which Franz attempts to explain to his father why he fears him so and begs for his judgment. We can never read enough this most naked of confessions in which Kafka transforms his father into a monster more encompassing than anything in Lovecraft’s loopiest penny dreadfuls, a spiraling and encyclopedic fusion of the Old Testament God and deeply-buried childhood submission, more haunting than any ghost and more homoerotic than anything of Anne Rice’s vampires (understandably, the letter was never delivered). In his genius-level capacity for obsessive suffering, Kafka got it right: Dad is the ultimate monster.