Reading Lists

7 Dark and Unsettling Books by Korean Women Writers

Chin-Sun Lee recommends subversive works of fiction about women fighting against the patriarchy

Since the early aughts, the cultural phenomenon known as the Korean Wave has expanded from a tiny homegrown ripple to a global tsunami of trends and merchandise encompassing pop music, gaming, cosmetics, cuisine, film and TV, and literature. K-pop bands now top the music charts, kimchi and gochujang are sold in most supermarkets, and Gen-Z embraces the K-dramas I scoffed at my parents for watching, while movies and TV shows like Parasite and Squid Games garner major awards and attract large viewership.

Korean representation in literature has emerged in a huge way as well, with women’s voices in recent years becoming predominant in books translated from Korean into English and also written in English by Korean American authors. I’ve noticed a bifurcation between the sunny innocence projected by K-pop and K-drama versus the gritty darkness, verging on noir and even horror, of movies like Parasite, Handmaiden, and Decision to Leave. Most of the books penned by Korean women also tend to be dark and unsettling. One reason for this, I believe, is the cultural pressure to maintain a harmonious appearance butting against the inner turmoil of that pressure to conform.

The surge of feminist literature stems from the country’s rise in gender equality movements in reaction both to #MeToo and the suffocating, centuries-long patriarchy of that society Like here in the U.S., Korean women are enraged and frustrated by oppressive societal norms and legislation that hold women back in life. Many of these author’s books, as well as those from their Korean American counterparts, reflect an existential longing for individual expression, gender equality, and solidarity with other women.

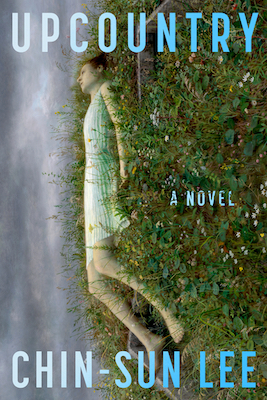

My debut novel, Upcountry, centers around three women from vastly different socio-economic backgrounds whose lives intersect in the aftermath of the 2008 recession: April, a middle-aged, impoverished single mother of three; Claire, her childhood playmate and a Manhattan attorney; and Anna, a young Korean American member of a local religious cult. For different reasons, all three women are outsiders in their small Catskills community, connected through tragedy and the secrets contained in the house Claire buys from April in foreclosure. At its heart, the novel is about class, faith, and the workings of fate, but the resilience of these women is the scaffolding that frames their world.

These books written by Korean women authors feature disquieting themes, complex characters, and narratives that articulate the inner lives of women in their unique interpretations:

Excavations by Hannah Michell

The disappearance of a beloved spouse after an accident is a torment few could fathom—but even worse would be to discover that spouse had a secret life. This is the horror that befalls Sae, a former journalist, when her engineer husband, Jae, goes missing after the collapse of a skyscraper in Seoul (inspired, no doubt, by the real-life Sampoong Department Store disaster in 1995), leaving her alone with their two small boys. As Sae searches for Jae and clues about his past, she encounters an old newspaper colleague, the madame of a prestigious room salon, and a thuggish executive from Taehan Group, the conglomerate responsible for the tower’s construction. The story skips back and forth in time: from 1992, when the tower collapses, to 1986 during the couple’s early days as student protesters, and then forward to 2016, as the dying elderly chairman of Taehan dictates his sanitized memoir. How these timeframes and characters fall into place isn’t a huge surprise—it’s less about whodunnit than why. The novel’s revelation, rather, is in its moving final chapters as we viscerally mourn the lives shattered through carelessness and grief in a conclusion that’s both an elegy and a scathing indictment of capitalism.

On the Origin of Species by Bo-Young Kim, translated by Sora Kim-Russell

It was the title and enigmatic cover depicting the top half of a female robot’s head that caught my attention. I’m glad it did—I’ve never read anything like it. Mystical and strange, this stunning collection is tonally reminiscent of the otherworldly, terrifying beauty of Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic masterpiece, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Comprised of seven longish stories, the standouts are the title story and its reprise where, long after the end of human civilization, robots inhabiting a frozen Earth begin to experiment with developing organic life, including new iterations of humans. This centuries-long process becomes a source of conflict, with some robots attributing godlike qualities to these new humans while others fear them as potential agents of their own extinction—a poignant mirroring of our own present-day fascination with and fear of AI. Kim’s references to science and technology never feel dry or academic; they’re simply tools of the language she uses in her imaginative exploration of human consciousness.

Cursed Bunny by Bora Chung, translated by Anton Hur

If you appreciate creepy stories mixing fables, folklore, sci-fi, and horror, then holy hell, do I have a book for you. This uncanny collection evokes primal terrors from childhood through tales about human greed, degradation, yearning, and retribution. But for all its darkness, there are moments of absurd humor, as in “The Head,” when a woman sees one protruding from the toilet and her husband says, essentially, “Eh. . .just leave it alone”—while “The Embodiment” pokes fun at the mechanics of Korean matchmaking. “Scar” is both chilling and heartbreaking, and even when Chung depicts horrific violence, as in the final scenes of “Snare,” her images have a startling, unexpected beauty. These stories, though written in simple, direct prose, are also piercing allegories for the corrosive nature of patriarchy and capitalism. Once I started this strange, brilliant book, I could not put it down.

Violets by Kyung-Sook Shin, translated by Anton Hur

Originally published in Korea in 2001, the English edition of Violets, translated by Anton Hur and published by The Feminist Press in 2022, feels strikingly modern. A damaged young woman, San, aspires to be a writer but after several rejections, finds herself working instead in a flower shop. Her outgoing co-worker, Su-ae, whose uncle owns the shop, befriends her, and the two girls become roommates. San finds solace in their company and in her daily tasks, providing the stability she lacked in her traumatic childhood. But her fragile psyche is upended by two men—a flashy, aggressive customer and a flirtatious photographer on whom she fixates—and the story takes a sudden, dark turn. I found the novel most compelling in its nuanced portrayal of mental illness, which doesn’t always manifest in obvious ways. The tender friendship (and nascent romance) between San and Su-ae is also handled beautifully. Without giving away spoilers, the ending truly upset me, leaving me with mixed feelings about the whole. But I can’t deny that the quiet power of this novel lingered in my mind for a long time after.

If I Had Your Face by Frances Cha

This gripping page-turner portrays five young women who struggle to lead meaningful lives in contemporary Seoul, where society judges harshly those without the privileges of wealth, status, education, or beauty. The latter, at least, can be obtained, though at great financial and physical cost. For Kyuri, who’s undergone several painful procedures, her beauty is her livelihood—she entertains businessmen at an exclusive room salon, while her friend Sujin aspires to do the same, scrambling to save money for her surgeries. Miho, an artist educated in New York, finds herself at odds when she returns to her home country; Ara, a hairstylist, carries a traumatic secret from her past that has rendered her mute; and Wonna, a slightly older, pregnant newlywed married to a man she does not love, frets about their precarious finances. Men impact their lives, as the culture dictates, but rarely in a positive way. Classism, sexism, and job insecurity press upon them all and while the novel ends in an earned moment of female solidarity, the teeming harsh world around them hasn’t changed.

Kim Jiyoung, Born 1982 by Cho Nam-Joo, translated by Jamie Chang

The cover’s surrealist portrait of a woman whose face is erased and supplanted by an arid landscape is an apt visual metaphor for this slim novella’s themes of female subjugation in South Korea. Kim Jiyoung is a wife and mother in her early thirties who, shortly after leaving her marketing job to have a baby, has a psychotic breakdown. When she starts speaking in the voices of other women, her alarmed husband sends her to a male psychiatrist for treatment. What unfolds is a documentation of her life under the thumb of patriarchy. Its short, straightforward sentences, often punctuated by footnotes citing instances of misogyny, connote a bureaucratic report of systemic institutional rot. While at times Cho’s message can feel didactic and heavy-handed, her depiction of the onset of Jiyoung’s psychosis is wonderfully bizarre and disturbing—and the novel’s conclusion has a satisfying, unexpected twist that’s all the more bitter for its irony.

Sonju by Wondra Chang

Sonju follows its titular character from her youth into middle age in the seminal years following WWII through the late ‘60s. Born into a privileged, class-conscious family in Seoul, Sonju is an idealistic young woman who hopes the end of war and Japanese occupation will allow her the freedom to pursue an education, career, and equal life partner. But her parents reject the young man she loves for his inferior social standing, forcing her instead to marry a stranger of “appropriate” status. Exiled to her husband’s faraway village, her life becomes increasingly unbearable through a series of tragic personal losses coinciding with the advent of the Korean War. When she finally leaves her loveless marriage, she is shunned by family and society and forced to survive on her own. Through this portrayal of one woman’s emancipation from the oppressive traditions she rejects, the novel draws parallels between her growing sense of autonomy and South Korea’s own trajectory of independence from Japan into a modern nation in its own right.