Reading Lists

7 Novels That Bear Witness to Latin America’s Dirty Wars

These authors interrogate the suppressed histories and horrors of colonial imperialism

Watching the steadily increasing discrimination against people from Latin America and the Caribbean [LAC] in the United States of America has been horrific; equally troubling is seeing the way in which certain people in the United States remain uninformed about their own country’s role in creating the conditions which force people to immigrate in the first place. For hundreds of years, the United States has treated LAC as its “backyard.” After the official adoption of this policy in 1823 via the Monroe Doctrine, LAC suffered decades and centuries of disastrous imperialist interference, corrupt dealings, and other violent events spurred by U.S. and European manipulations. In the 1960s and 70s, this came to a head when CIA-backed military governments in LAC led to a cascade of what became known as “Dirty Wars” across the region. I first heard the term “Dirty Wars,” after being assigned two of these books as readings in a class about gender, violence, and politics in Latin America during university. I’d taken the class as part of my process of learning about the region my grandparents had left in the 1950’s, when they decamped to the United States in search of a better life.

These are books I’ve been lucky enough to read through my own research interests about colonialism, imperialism, resistance, memory, and magic in LAC. Surrealism pervades multiple books on this list because, in the words of Gabriel García Márquez, “The problem is that Caribbean reality resembles the wildest imagination.” This holds true for both the horrors of colonialist-imperialism and the beauty of life in LAC. I prize these novels for reflecting the authors’ experiences of actually having lived in LAC during the events they discuss (in Héctor Tobar’s case, this includes blending personal experiences in L.A. from the 1990s with the legacy of his Guatemalan heritage). The following seven books are works of historical fiction about events in LAC which touch on the Dirty Wars. Each of them has helped me in my own process of self-education about these intentionally suppressed parts of global history.

The Tattooed Soldier by Héctor Tobar

With a narrative switching between Guatemala of the 1980’s and Los Angeles at the beginning of the 1992 Rodney King riots, The Tattooed Soldier is a harrowing read about trauma, complicity, and Guatemala’s Civil War and Guatemala’s Civil War (which ran from 1960 to 1996 and is also known as the Mayan Genocide or the Silent Genocide). Two Guatemalan men—Antonio Bernal, whose wife and child were murdered by the military, and Guillermo Longoria, a former soldier—immigrate to Los Angeles to escape the ashes of their past. Guillermo, an Indigenous man, is a victim in a different way than Antonio: he was kidnapped and brainwashed by the military after sneaking away from his shepherding duties as a teenager. The two men’s lives run in parallel vignettes of both the past and present, with tension rising as their new lives in L.A. begin to converge. This is an elegant story about Guatemala’s Civil War against the backdrop of the enduring issues left behind by the Civil War in the United States of America.

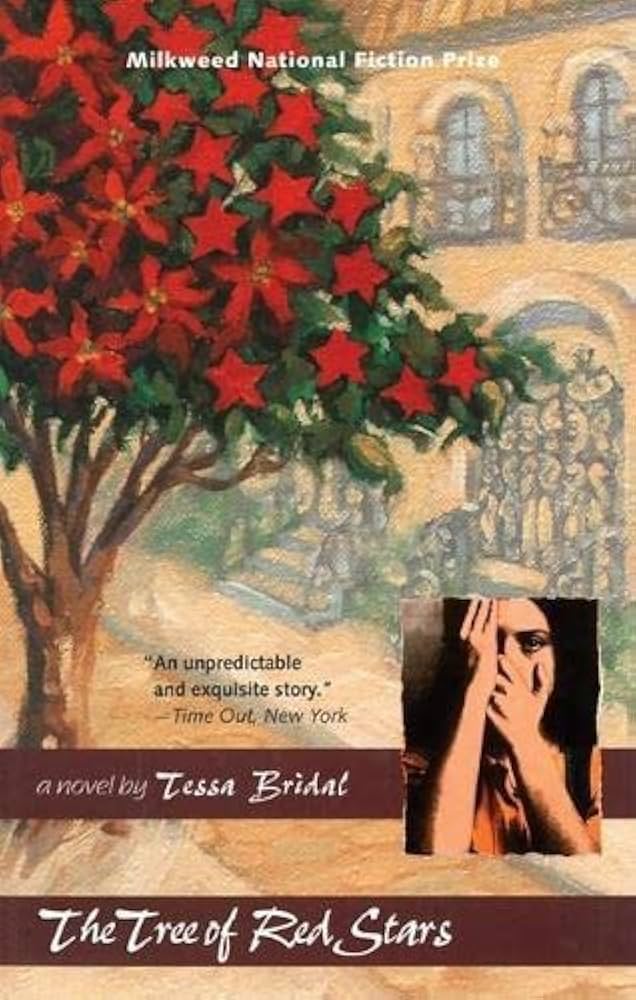

The Tree of Red Stars by Tessa Bridal

The winner of the Milkweed Prize for Fiction, and the Friends of American Writers Fiction Prize, The Tree of Red Stars is a fictional account of its author’s childhood. Told from the perspective of Magda, a sheltered young girl of Uruguay’s elite class, Bridal gives a candid illustration of how the privileged are allowed to be passive, shielded by wealth, until conflict arrives at their doorstep. The title of the book refers to the flowers of the ceibo tree, which is the national flower of both Uruguay and Argentina. Attached to the flowers is the legend of a Guarani woman named Anahí, who resisted Spanish colonization in what is today Argentina—Spanish soldiers attempted to burn Anahí at the stake, but when the flames touched her skin she was transformed into a ceibo flower. Madga’s sacrifice as a privileged, European-descended Latin American is a far cry from Anahí’s, yet she too pays for her revolutionary affiliations.

Our Share of Night by Mariana Enriquez

Our Share of Night is acclaimed Argentine author Mariana Enriquez’s masterpiece. Centering around the Argentinian Dirty War (1976 – 1983), Enriquez crafts an alternate reality in which the Argentine dictatorship is supported by a cult of would-be magical practitioners known as “The Order,” who all belong to the country’s elite, European-descendant, millionaire, landowning class. Enriquez skillfully demonstrates the way colonial violence and the accompanying abusive power dynamics of Europe’s wealthiest families have impacted generations through The Order’s exploitation of marginalized mediums—people capable of communicating with the ravenous entity The Order serves, known only as The Darkness. Switching between viewpoints of the latest medium: Juan, his son Gaspar, Gaspar’s mother Rosario—the heir apparent to The Order—and a journalist assigned to investigate a mass grave of disappeared Indigenous people and activists, Our Share of Night is a terrifying and captivating portrayal of the real-life horror movie that was Argentina’s military dictatorship.

The House of the Spirits by Isabel Allende

Isabel Allende, cousin of the overthrown, democratically elected Chilean president, Salvador Allende, is the author of the surrealist, at times humorous, often sorrowful epic that is The House of the Spirits. This novel tells the socio-political story of Chile in the early and mid-20th century by following three generations of the Trueba family and their lovers, associates, and enemies. All the book’s events radiate out from the central foci of husband and wife, Esteban and Clara Trueba. Clara, around whom the novel’s events begin, speaks to spirits, predicts the future, and levitates objects. Esteban, symbolic of the conservative influences behind Chile’s anti-socialist opposition of the time period, imagines himself to be a man of traditional values and good character, yet he exploits, cheats, and beats his way through life. The book is a noteworthy reflection upon the ways in which conservative politicians are often revealed to be hypocritical of their espoused values.

In the Time of the Butterflies by Julia Alvarez

After her father’s involvement in a failed plot to overthrow Dominican dictator Rafael Trujillo in 1960, Julia Alvarez and her family fled to New York. She memorialized the thirty-year dictatorship and Dominican resistance to tyranny through the real-life activist Mirabal sisters—Patria, Minerva, and Maria Teresa—who were known as Las Mariposas, The Butterflies. Cycling through the perspectives of all the sisters, the book begins and ends with Dede, who chose not to join her sisters’ guerrilla activities. Drawing on themes of class, gender, family dynamics, and survivor’s guilt, the book follows the Mirabals as they develop into revolutionaries. Ironically, though Dede did not want to be involved, she is the one who keeps the memory of their bravery in the face of tyranny and patriarchy alive. Perhaps that is Alvarez’s metaphor for how we cannot escape being a part of the revolution in the end, no matter how much we try.

Kiss of the Spider Woman by Manuel Puig

Iconic in Latin American 20th century literary history for its inclusion of a gay character, Kiss of the Spider Woman is the dramatic tale of Valentin, a revolutionary, and Molina, a gay man, who share a cell in an Argentine military prison during the Dirty War—Valentin for his guerrilla activities, and Molina for the crime of homosexuality. Much of their conversation focuses around Molina telling Valentin the plots of films to pass the time and distract them both from their predicament. Slowly, Valentin begins to reveal personal details about his life and work to Molina. The book gives complex character portrayals of a revolutionary and a gay man during a time in which both are oppressed, but without fully escaping stereotypes about masculinity. The reader watches as their relationship, imprisoned together in the dark of a cell, develops and ultimately reaches a critical test of loyalty that has ramifications beyond the prison walls.

One Hundred Years of Solitude by Gabriel García Márquez

One Hundred Years of Solitude centers around the Buendia family, whose patriarch founds a town named Macondo in the jungle, a place steeped in magic and surrealism. Macondo reflects the trajectory of many LAC nations: Conservatives and Liberals are in constant conflict; the arrival of U.S. businessmen transforms the region into a monoculture economy; there is organized resistance, military violence, racial hierarchies among mestizos, Europeans, and Afro-Latinos; and ultimately, corruption is created by wealthy families, the Catholic church, and political figures. By referencing the Banana Massacre of 1928, in which the Colombian Army, on behalf of the United Fruit Company—now Chiquita Brands International—massacred striking plantation workers, Márquez memorializes an incident of U.S.-backed violence. One Hundred Years of Solitude is also notedly the only fiction book I have yet to read in which antillanos—descendants of West Indians who migrated from Caribbean Islands to Latin America, the ethnic group I belong to—are represented.