Reading Lists

7 Poetry Collections by Women Rewriting History

From the Paleolithic era to the Salem Witch Trials, Katy Simpson Smith recommends verse that takes a deep dive into the past

I am a novelist, but in my heart I know the grandest thing to be is a poet. We often mislabel poetry as being essentially presentist: the author/narrator gazes out the window, in a mirror, at wheelbarrows. But all writers have the whole scope of history to muck about in; the best historical poetry, like the best historical fiction, plays with the very premise of the past.

My new novel, The Everlasting, leaps from today to the 16th century to the 9th century to the 2nd century, following a series of lost and loving souls in Rome. One of my narrators, the Devil, is what I might call a poet of history, in that he understands its accordion nature and takes pleasure in disturbing the humans’ sense of time and order.

Those who dive into the rich waters of before know that meaning is made through questioning, comparison, rupture. Why bother dead bodies if we’re not going to poke at them? The seven collections here make just the sort of playground of history that causes this ex-historian to rub her hands together. The past is now; the dead are alive!

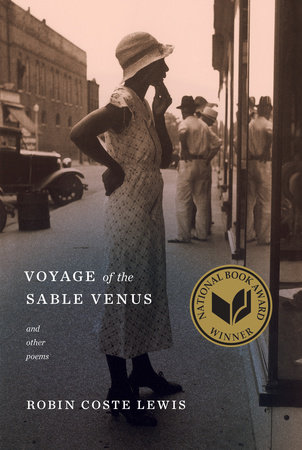

The Voyage of the Sable Venus by Robin Coste Lewis

The eponymous poem of this collection, some eighty pages long, is a directly transcribed list of the titles of “Western art objects in which a black female figure is present” from the Paleolithic era to the present. That the titles are unedited contributes to the poem’s mounting sense of violence, both art historical and literal. “Statuette of a Woman Reduced / to the Shape of a Flat Paddle,” begins one catalog; “Partially Broken Young Black Girl / Presenting a Stemmed Bowl // Supported / by a Monkey.”

Memorial by Alice Oswald

In this translation of the Iliad, British poet Oswald cuts out everything but the similes and the parts where people die. Sounds simple enough? Her radical vision of an “oral cemetery” feels like a truer accounting of the Trojan War than Homer’s. What is war but death repeating like a wheel, names swallowed by a wall of sound?

The Afflicted Girls by Nicole Cooley

The Salem witch trials are always ripe for a retelling, and here Cooley injects her own archival journey, interspersing hair-raising and pitiable accounts of accusers and accused (“We’ll choke, hold our throats closed with our breath, until / the women disappear”) with the trial of saying anything new (“I fling / my voice . . . down history’s corridor / crowded with everything that has already been said”).

Thrall by Natasha Trethewey

The always historically minded Trethewey (Bellocq’s Ophelia, Native Guard) picks apart the caste system of the 17th and 18th-century Spanish colonies, pointing to the origins of mestiso and mulato, those same blended cultures and colors that left her a legal anomaly in 1960s Mississippi. She is fearless here, confronting figures from Velázquez to Sally Hemings; “I’ve made a joke of it, this history / that links us – white father, black daughter – / even as it renders us other to each other.”

An American Sunrise by Joy Harjo

Harjo’s lesson about time’s cyclical chaos is unflinching. In her preface, she links the 1830s Trail of Tears to the trails that indigenous peoples keep taking, are still forced upon, those paths that rupture homelands in the name of—what? Colonialism? False security? The toxic burn of dispossession? “History will always find you,” she warns, “and wrap you / In its thousand arms.”

The World’s Wife by Carol Ann Duffy

History needn’t be so serious all the time; indulge in Duffy’s biting retellings of the lives of Great Dead Men from their wives’ perspectives: “Mrs. Sisyphus,” “Queen Kong,” and “Frau Freud.” Imagine a history where Mrs. Darwin observes, “7 April 1852. / Went to the Zoo. / I said to Him – / Something about that Chimpanzee over there reminds me of you.”

Rice by Nikky Finney

The best history starts from the bud of the personal, and in Rice, Finney pays homage to her South Carolina heritage. In poems like “The Afterbirth, 1931” and “Making Foots,” she challenges the solemn distance of standard tellings of slavery and Jim Crow.

“Many a foot / was chopped / off an African high-grass runner / and made into / a cotton-picking / plowing peg,” she writes, adding, “If your Black foot / ever wakes you up / in the night / wanting to talk about something / aching there / under the cover / out loud / for no apparent / reason // There is reason.”

Kwame Dawes calls this book “herstorical”: it does not instruct, but reclaims. May we all approach history so humbly.