Craft

“A Faded Sense” by Dina Nayeri

A story about sensing without being able to touch

EDITOR’S NOTE BY HALIMAH MARCUS

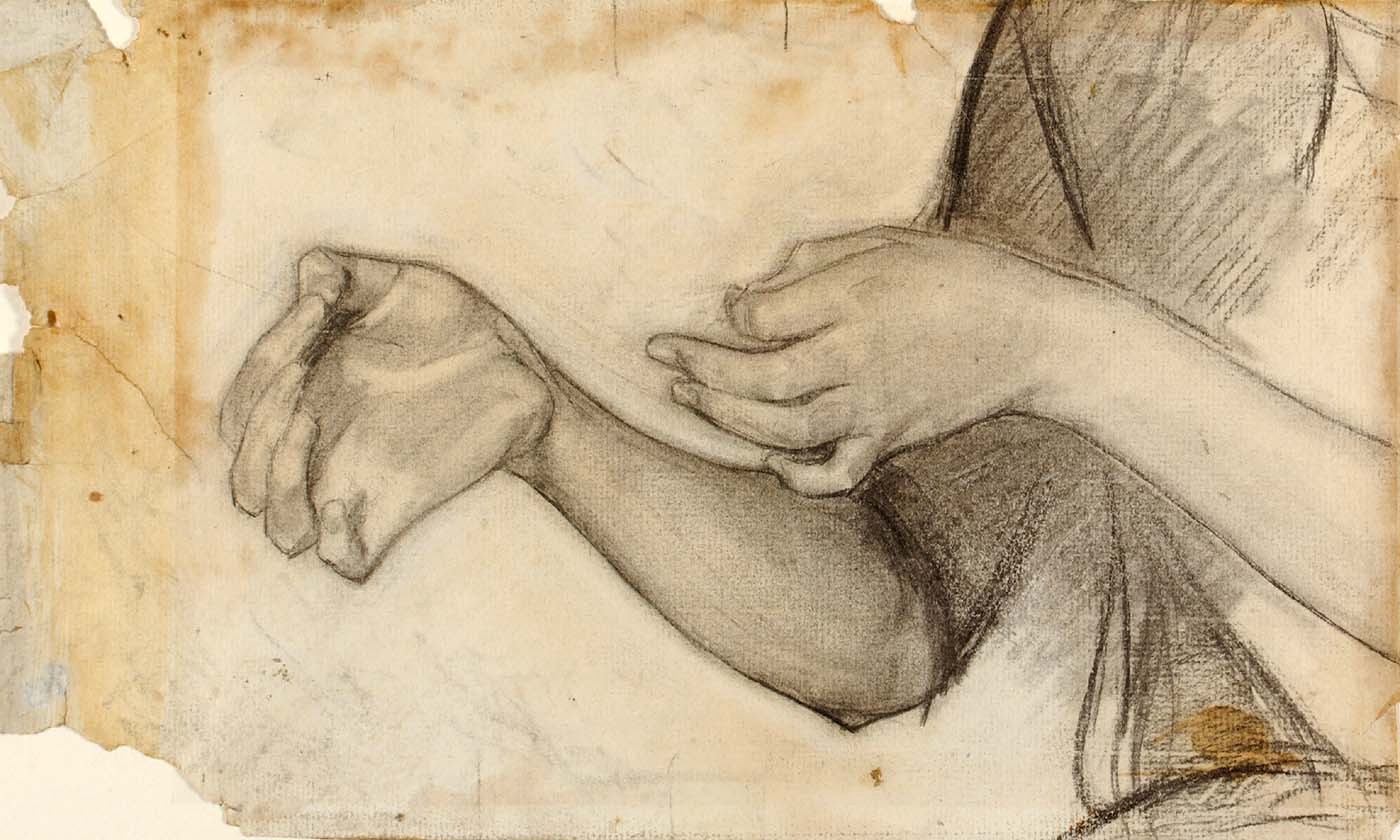

Sara, the narrator of Dina Nayeri’s “A Faded Sense,” has only four out of five senses in tact. Her sense of touch — the most intimate sense, the only one that requires being close, within arms length — has been drastically diminished by a childhood accident that badly scarred her palms. Though the injury itself was brutal, the cause wasn’t particularly violent — the equivalent of tripping — or, as Nayeri puts it, “a lifetime of mild punishment for a single bad instinct.”

One morning we find Sara “grinding [her] fingers into a bed of uncooked rice,” hunting, she says, “for deeper sensation.” I’m reminded of something I once read about children forced to kneel on uncooked rice as an abusive punishment, and the parallel offers insight into Sara’s mind. What is torture for others is an exercise for her — a matter of regular practice. She turns over painful thoughts like sharp pebbles in her fist, daring them to make her feel more than “a faded sense.”

And yet, despite Sara’s faculties not being entirely in tact, Nayeri’s are operating at full capacity. Some of the greatest pleasures of reading “A Faded Sense” are the author’s sharp and touching characterizations: a loving email from Sara’s mother that she deletes immediately after reading — the kind of tender advice only a daughter could take for granted, “finding love, is not finished.” Or, the reverse of that, the cruel remarks her brother makes, the kind of truthfulness only a sibling could get away with: “It’s like your arrogance and actual uselessness are wandering around in all that dark. When they finally bump into each other, you’ll probably commit suicide.” And between the two of them, there’s Sara addressing herself: “I think about getting my shit together, what that would look like.”

Unlike Sara, who describes her injury as being “like trying to appreciate silk through dish gloves, or the watery trickling music of a harp through a thick door,” the reader experiences this story with stunning immediacy, with a heightened sense of what it’s like to be this person, this Sara, with her heavy heart and her damaged hands.

Halimah Marcus

Editor-in-Chief, Electric Literature’s Recommended Reading

“A Faded Sense” by Dina Nayeri

Dina Nayeri

Share article

Recommended by Electric Literature

Original Fiction

Isaac sips scotch with slow winces and tells me you can use stomach fat to fill the hole left from excising a neck tumor. “That’s the simple part. I’d let a first year resident do it.” We sit at a table close to the door and every few minutes a chilly wind follows a customer into the bar. A dried-out lime wedge flung partway between us leaks a drop of gin onto the wood.

How much can a first year resident know? I used to tell my brother Kian that if you gave me five years with no distractions, I could do anything: surgery, rocket science, ice dancing. He sneered, a reaction I had counted on when I said it. “What happened to you?” he once asked me, all disdain and misplaced pity. He was a little drunk. “It’s like your arrogance and actual uselessness are wandering around in all that dark. When they finally bump into each other, you’ll probably commit suicide.”

He said that before Arash — of course. I’m supposed to do everyone the courtesy of forgetting. I only remember the one comment, and another, more recently, at Norooz dinner. Kian, after a few glasses: “You know why Sara dates so much? ’Cause when other people are alone, they get to be with a sane person.”

Since last summer, I go on dates for the stories, and to calm my panicky friends, but really just for the stories. I tell the men I’m divorced. The truth is that Arash died in a motorcycle accident on the NJ Turnpike the day after he told me he wanted to leave. He was rushing to a meeting with an author at Princeton when a rig in front of him had a blowout. He swerved to avoid the chunks of tire and hit something that sent him into the wheel of the truck. A witness said he flipped his bike four times. So, in a way, the awful conversation of the previous morning didn’t happen. He never stroked my chin with one hand, never massaged my palm and dropped his voice and said, “Sara joon, it’s perfectly possible for me to love you and to feel that our marriage isn’t working. Those two sentiments are possible for me.”

But, wherever Arash has gone, we both know that he did say those words, and so calling myself divorced seems more honest. I have a hundred ways of finding these men — through friends, online, in magazine articles about loss or illness or war. I ask them out, they always say yes, and we have a good time together. I found Isaac quoted in a piece on throat surgery.

The bartender plays strange music. After Laughter by Wendy René.

I rub my palms together, then against my bracelets. This morning I spent half an hour grinding my fingers into a bed of uncooked rice, turning the flesh into a tenderized ruin as I hunted for deeper sensation. Some days the numbness and false itching intensify and I have the urge to press sharp things into the pits of my cupped hands. To wrap my fingers around a cactus. To massage a bunch of pine needles. Once I joked that crucifixion might be pleasurable. Maman gasped. Kian laughed into his coffee mug. “Jesus, Sara. Stop making it a thing.”

Isaac has careful, elegant hands — they’re his livelihood.

Lately I’ve been pulling the bricks out of Arash’s office wall, one by one. It was a healing project at first — building a reading nook. But then I thought of our last trip together to the north of Iran, the watery rice fields and thick, wet mountainside foliage near the Caspian Sea. We spent a lot of time with our notebooks open in fish fry shacks, the ones set up on stilts just past the shore or on a pier. In the mornings we hunted stories that we offered to each other, like wedding sweets, over simple fish lunches seasoned by the salt in the open air. Dramatic sagas of love and sex made Arash laugh, so I investigated those while he did real work — interviewing ex-prisoners. All day long I spoke to fishermen’s wives who made up superstitions as they cooked. Wrinkled and bent, they delighted in pulling folksy gems out of the ether while the waves whooshed up and licked the windowsills of their fish shacks and the last filets went into the frying pan. A surprising lot of their wisdom had to do with stuffing things into cracks of walls for luck, for blessings, for warding off jinns. “For a passionate marriage, put jasmine and orange blossom in the wall every day.” “For the life to return to your poor hands, put chicken beaks and feet in the cracks.”

When I complained about my lot (his story was going to Harper’s and I was kicking it with grandmas), Arash said, Don’t judge the work you’re given, Sara joon. Just write the truth. Wishing back that moment, I change it so I don’t roll my eyes.

So now the office wall: it’s not some kind of magical thinking madness. I don’t have any delusions that he’ll come back hungry for material. I want to honor his cheesy Isfahani poet-boy philosophy. So I started typing up my callus hearted attempts at new love and stuffing them in the holes behind the bricks — for you, Arash joon. For a death filled with the truest stories. May you rest in eternal drama.

The best stories, Arash would say, aren’t complicated or grand. Forget about war and politics and death and suffering. Sure, those pay the bills, but for the good stuff, dig down to the bruised bones. The whine of sitting-room poetry, dusty drawings brushed with turmeric and crushed petals, two overplucked strings beside two broken ones. The last joyful noise in a crush of wailing.

I stare at my date, this good surgeon, his hopeful face, a little pocked and somehow reminiscent of an overdrawn cartoon mouse (I hate to mention Iranian noses), but eager, a kaleidoscope of expressions that make him beautiful. Who goes on a first date with hope anymore? How did he hang on to it after New York, after tumors and tsunamis and the Arab Spring… after cutting into his first corpse? Wounds are ugly. Doctors must crave to get away from them; Isaac probably doesn’t get that many nights off just to be drunk and happy.

“So then,” I say, hands gesturing, because isn’t it nice when you lose your own thread for a minute and peek at another part of the tapestry? “You put a slice of fat from the belly into the tumor hole.” Isaac nods and leans in. He seems a different kind of Iranian — rational and calm, and Jewish. I like it. “How do you know the tumor won’t grow back?” He shrugs playfully and touches the top of my hand. I let him. “Do you melt the fat first? And how much fat-slicing has a first year intern done already?” He laughs gently, privately, like he’s just seen a small sign on the table, a ladybug or some Persian script carved into the wood. I ask, “How big is the slice?”

What grotesque behavior — why do I always want to become these men? Why do I want to crawl not into their clothes, but into their skin?

And yet, slowly, his smile changes, it melts and drips past his lips and cheeks. The shy doctor is happy right now. I’ve made him happy with my silly questions. What I’m thinking is that I would’ve killed at his job — would’ve made a badass lady surgeon, the kind that makes jokes and strokes your nose as you’re slipping under.

Not that the written word is a thing to dabble in, or scoff at, or feel like you have to explain on blind dates. Truth and beauty, Arash would say. You and me, Sara joon, we’re in it for truth and beauty.

“I might go to Kabul,” I say, out of nowhere. “Next summer. Maybe to look for stories.” Then, because I feel like a fraud, aping my dead husband like a fake widow with no plan of her own, I add, “Not political stories like Arash wrote. I want to write about the hidden stuff. The stuff that gives people joy… Food, music, grandmothers.”

“What a cool life,” Isaac says. “Are you close to your grandmothers?” He doesn’t ask who Arash is.

Two hours into the blind date, I’m down to the ice in my third gin-and-tonic and trying to be purposeful about what I notice in Isaac’s face and mannerisms. He brags in an affected sort of way. Insecure asides like, “I’ve tended to lose interest every time the chase is over.” I’m tired. There’s no new story here. He fixes necks.

He says, “You know, a measure of beauty is the distance between the arch of the eyebrow and the brow bone. Yours is high, especially when you raise that one.”

“I’ll thank Uma the wax lady.” Why did I say that? Why do I ever say things?

Isaac’s lips curl in two places when he talks, a slow rolling like caterpillars waking. It’s strange and intensely sexy. He talks with (and about) his hands a lot. I would bet my meager fortune that he has moisturizer in his jacket pocket. I focus on the movement of his thumbs over mine. They’re very deliberate.

“Tell me about the scars,” Isaac says, out of nowhere.

It’s too late to hide them, and he’s still touching one of my fingers, so I tell him. I never have trouble sharing stories, even when I do have trouble, and then I tell them better. “People don’t usually notice,” I finish. I untangle my fingers from his and slip my hands down onto my lap. “They’re so faint now.”

He nods, “Scars are interesting. I have one on my jaw. See?” he lifts his chin.

I feel my charm draining. The bar smells strongly of grapefruit. “It’s time to go home,” I tell him. He pays for our drinks and says he’ll call. I pretend I don’t know that he’ll write in precisely four days, an email he’ll draft tonight and save. He seems incapable of writing two hours from now. Two hours from now, he’ll be carving up and negating all our best moments in his head — the truest ones that need no editing.

In the morning I call my brother, when I know he’ll be walking home from the gym, cheerful and not screening. I tell him about my night. He listens and listens, offering nothing. “Whatever feels right,” he says twice before I ask him what it is exactly that he’s judging about my story of Isaac the surgeon. He takes a moment. “I just think it’s lame and artificial to go out with people only because they’re Iranian.”

“I didn’t though,” I mutter. I want to add that this isn’t about Arash. It just comforts me to speak Persian. It makes me feel like I’m using my education — Persian is an advantage I should have been granted at birth, but instead won the hard way, a reward for study and hardship. Each syllable is savory and complex on the tongue, a new kind of nourishment, like morsels of food you’ve chopped and seasoned and cooked with your own hand, every spice and herb distinguishable to your palate. I want to tell Kian that speaking Farsi to men makes me feel something like love, and isn’t it a relief to feel love now and then? Love for the universe, for people as a whole rather than just one? Doesn’t it make the world open up, like a knife twisting open the hard shell of a chestnut? But I’m too embarrassed.

“Just go out on a real date,” he says. “Go out with a white lawyer.”

“I like the ones that can do something with their hands… a hard skill. I don’t know…” I stare at my own hands. Do I blame Kian for them? Yes, but…

“You mean, like you?” Ouch. He adds, in a kinder tone. “You’re being a snob.”

But once I restrung a rope of pearls in twenty minutes.

Once I pushed out a bead stuck in a toy train with a needle.

Once I fished an earring from behind the oven with a wire hanger.

When we were teenagers, on a summer trip to Tehran, Kian and I tried to restore a beat-up Toyota, not an unusual project in a country where everything is turning to junk, and I badly burned both my palms. It’s funny, a lifetime of mild punishment for a single bad instinct. Kian was fumbling over the engine — he’d taken a handful of lessons from a local mechanic. In the daytimes, if I was bored, I helped. The rod was missing, so he asked me to hold the hood open. When it got hot, I dropped it, then tripped trying to keep it from landing on his head. I fell onto my hands right on the scorching engine and, panicking, pressed down harder trying to lift myself. Kian wrapped my hands in a wet t-shirt; it stuck to my blisters when it was peeled back later at the hospital. The scars have diminished now — aside from the strange lines, the hardened, uneven skin — but for a month I lost all use and sensation in both my hands. During those weeks, I watched my mother wash basmati rice and bake cakes with her sisters, and for the first time I was jealous, terrified that I would never do anything so mundane. Now, it’s just a faded sense, like trying to appreciate silk through dish gloves, or the watery trickling music of a harp through a thick door. I’ve mostly forgotten it.

Kian is right. Since Arash asked for a divorce (and then died), I’ve only written a few stories — if you want to call that work.

I’m defeated, but I persist. “Can you be a snob against a white lawyer? How?”

“You’re a trade snob.” He laughs in that Kian way, eyes smiling (I know) as he climbs the dark staircase to his Lower East Side studio. I drop the argument. Before we hang up he says, his keys jingling in his door, “Just get your shit together, sis.”

Later I visit Maman’s cake shop on Bowery. I find her in the back, her hands positioned six inches apart on the plastic piping bag, fingers kneading, elbows locked at an angle, eyeglasses falling onto her nose. Her tiny body hovers over the modest cake like a craftsman over some enormous sculpture, squeezing out her rosettes with such care. When I tell her about my date, she says, “Is still so early.”

I get a break tonight. I’m hanging out with Andy, a gangly bass guitarist who tends bar on off nights. Often he shows up to wherever we’re going with cuts on his knuckles from broken glass, or drying scars slicing his unshaven chin. I don’t have to be smart for Andy. I don’t even have to get ready. I can just arrive at the bar wearing my day clothes, drink too much, eat fries, say stupid shit, and he’ll still fuck me with his eyes. He’s bought us tickets to a jazz band, a sit-down space with plastic wine glasses filled to the rim for five dollars.

Before we’ve exchanged three sentences, Andy kisses me on the steps leading down to the basement venue. It’s our first kiss. He’s standing on a step below me, his face close, so he just decides this is a good way to spend our time stuck in line. Other people linger above and below us on the steps, trapped there, watching us kiss. I imagine Isaac, his careful caterpillar lips, incapable of boldness. Somehow this knowledge thrills me; it electrifies Andy’s fingertips as they crawl down my spine.

I want to scratch my palms on his beard.

At the table, Andy sits on the couch side and pulls me beside him, roughly, by the elbow. He wraps me in both his arms like I’m his discarded coat, like he’s trying to fold me over. All through the set, he taps to the music on my thighs, on my belly, on my knees. Sometimes he tastes my earlobe when the beat is slow. Once in a while, his fingers follow the chords on my arms and legs; he slips his hand under my skirt and plucks the elastic of my underwear like strings, our own secret set. Even with my ignorance of jazz, I can feel that he’s following the song exactly. If I close my eyes, I have the strange experience of becoming the double bass.

When Andy likes a riff, he moans, “mmm hmmm,” as if co-signing every note. He applauds by clapping my thigh, then, as the music dies down, slides his free hand around my neck. The gesture feels like a violation, but I like it. The room is chilly and the bassist rests his hand on his instrument’s neck in exactly the same way.

A sudden, unwelcome memory of Arash’s hands on my cheeks rouses a wave of nausea to the spot Andy is gripping. I hurry to replace the image with Isaac’s tentative, precise fingers on mine, a thumb moving in circles, casually exploring my scars. Think of all that his fingers must know, given years of training: how to judge a shiver, a callous, a spot of heat. He is heightened in the same ways I’m dulled.

When the band takes a break, Andy stares into my eyes in an uncomfortable way, as if he thinks we’re in love. I glance around at the mostly college crowd. I want to chatter, to keep him from staring at me with all the expectation of a dim-witted child. “If there was a nuclear war, who do you think we’d need to rebuild the world?”

He squeezes my arms. He’s annoyed. “Artists,” he says without a thought.

“That’s dumb. I’m serious… who would be indispensable?”

He loosens his grip. “I am being serious. That’s my answer.”

“So you’re bleeding from an artery and you want a pianist or a cake designer or guy who makes bird sculptures? Come on, Andy.”

“Cake is food,” he says. “And I assume people still have souls?” His arms tense and I can feel him trying to decide whether to untangle from me. He doesn’t want to, but is insulted and thinks that he should, that another man would.

“Don’t be a priss, Andy. I’m too tired to deal with your shit.”

“My shit?” he says with mock indignation and pushes his hand roughly up my shirt. He pinches the flesh below my arm. “Can’t deal with my shit, says the lady.” He tickles me hard. “Well then… ”

I chug the rest of my wine and burp into my hand.

“Sexy,” he says — or something like that. Something that implies that I should want to be sexy for him. Men have all kinds of nerve. I am sleepy and content.

“Move over.” I force his arms back around my body so I can lie back against him. For the rest of the night, Andy’s hand is inside my shirt, tapping out the rhythm on the skin just below my breast, where I have a mole he seems to have discovered.

I only gained back about forty percent of the sensation in my hands, and even that took almost a year. This means that, even now, I find myself touching things without knowing. Sometimes I drop things, but not often. Most of what I’ve lost is fine touch: the detail on the face of a coin, the sensation of feathers, a kiss on the palm, the tickle of stubble. Some of these I was too young to know and so they’re lost from my collected experience. What should it feel like when I touch Andy’s face just after he’s shaved? And a day later? Often I press when I mean only to touch. I shake hands and pet animals too firmly. I check the water temperature in the shower with my wrists. But, as I grow older, fewer people notice. I’ve learned to temper my natural instincts to press and squeeze and scratch at my rough palms.

After the concert Andy holds my hand and we stand on the sidewalk near the Village Vanguard, checking our phones. Groups of tourists, NYU students, and music geeks hurry past us as we linger. I have an email from Isaac, sooner than I expected. He says last night was fun, asks me to dinner. “I knew he’d write,” I say out loud.

“You knew who’d write?” says Andy, glancing up from his phone.

“This doctor from last night.” Andy doesn’t drop my hand. Just smirks at me for a beat too long, trying to make me uncomfortable, then turns back to his phone. He has a specific way of holding my hand, gripping tightly, every square millimeter of skin compressed against skin. He never loosens up. Sometimes with our fingers interlaced, he rubs his palm in an aggressive circle against mine, or slips his thumb between our clutched hands and presses hard, drawing a long line. I told him about my accident the first day we met, when I was drinking alone at his bar shortly after Arash died. I’m not sure why I said it; maybe I knew there was nothing there.

What I never told him is this: Arash used to massage each of my palms with both thumbs — twenty minutes each. He would lock our intertwined fingers in place, using them as leverage as he worked his thumb hard across my lifeline.

At home I rub lotion onto my feet until I no longer feel the roughness in my heels, then I rub two more layers to cover the sixty percent. I fall asleep without brushing my teeth. I think about getting my shit together, what that would look like.

Isaac takes me to dinner at a bistro near NYU Medical Center, because he’s on call. His scrubs are in an overnight bag next to his chair. He can’t drink. But he orders white wine for me and we share mushroom pasta and roast chicken. He seems to have the instinct to care for people, which isn’t typical in men our age — by your mid-thirties, unless you have a family, you learn to care for yourself, to tune out all the other walking and talking receptacles of impulse and need.

Afterward, we walk to his apartment. He lingers on the steps to his walk-up and makes a show of checking his work phone, then inviting me upstairs as if the idea just occurred to him. “All clear,” he says, “I have no plans if you don’t.” Who makes plans after a dinner date? He suggests we make s’mores and tea, which is a sweet alternative to Andy’s Neanderthal ways, killing time in a box-office line.

Isaac has no kettle, surprising for an Iranian man (between us, Arash and I had three), so we watch the water boil in a pot, standing two feet from each other, arms crossed. Finally he takes my hand and pulls me closer, starts to kiss me. Everyone should have soft, rolling caterpillar lips like these — it should be the next step in human evolution. I articulate this in my mind hoping Arash can hear. Isaac turns off the water before it’s finished boiling. “I guess we’re not having tea,” I say.

He laughs. An easy, joyful laugh.

Stumbling through the apartment, he breaks my pearls. They scatter everywhere, a shower of bobbles that create a beautiful patter, like a hard rain or knuckles drumming on his hardwood floors. He stops, wanting to pick them up, but I lie and say they’re fake.

We make love in his tiny, brick-walled bedroom, where I discover he has habits I’ve never known. Maybe I haven’t been with enough men, or any good ones. He draws on my body with his fingers for a long time, objecting each time I move or speak. At first I feel strange, like I’m a collection of parts that he is examining. He caresses my cheeks with his face, though such plays at a deeper romance are hardly necessary at our age. He presses against me with his stomach, thighs, and chest, spreads my fingertips and kisses them. He brushes the pads of his fingers lightly against my stomach, then down toward my hipbone, and my own fingers seem to come alive. Isaac smiles as if he knew this strange connection between the nerves.

Later, when we are well into it, and he seems to have fallen on instinct, he grabs my wrist and pushes my hand down between us. Wrapping my fingers around himself as he slips halfway out, he whispers, “I want you to feel it with your hands.”

It seems cruel, now, after all that feigned romance.

I touch him, but all I feel is some wet heat, the faintest friction, and the familiar details of my own body against another. There’s no room between us to reposition my grip as he moves, but I want to try. Obviously there is something here that he wants me to experience. I wish so much to break through my own outer layer, to feel this moment gloveless, skinless — the way Isaac feels it. I close my eyes and struggle, trying to force my imagination to make up the difference. This isn’t the way I make love. It feels like a dissection. In the end, whatever mystical union I’m supposed to sense is covered in the same awful film that I’ve been unable to scrub away for two decades.

He isn’t stopping. His lips hover close to my ear and I fight the instinct to squeeze. For a moment I entertain it, this ugly impulse that overtakes me every time I come across something silky or textured or delicate — desperation to press. In my palm Isaac and I are nothing more than sterile objects, dead, like pieces of plastic sculpted to fit together.

Once I submerged my hands in a vat of Maman’s cake batter, kneading and praying to feel the goo between my fingers with the same intensity as I did when I thrust my hand in a vat of Vaseline at five years old.

Once I slapped Arash’s face on a dance floor, because I wanted to feel the sting on my fingers, that first layer of skin that I was missing.

Once I spent an hour with my fingers over a candle flame, hoping to burn away the invisible gloves.

Even now, I want to slap Isaac. My fingers itch for the contours of his face. Instead I shove him off and roll over, pulling the sheets toward me as I turn from his bewildered expression. I am helpless against the tears.

We end up having the tea, after all. Isaac doesn’t seem bothered. He wraps me in his plush white winter robe and we sit on the couch drinking Darjeeling with mint. He is the kind of man that drinks Darjeeling with mint after sex. This is a moment for a cigarette, bodies half hanging out of a window, a walnut cake and sweet tea with cardamom.

“Can I try something?” he asks, after two cups drunk in near silence.

“Hmm?” I say and rub my eyes. I’m ready to go home. “Sure.”

He slides toward me on the couch and takes my hand. He picks up one of my pearls from the coffee table, where we discarded the decimated string in the frenzy of an hour ago. “Grip this,” he says, and I do, though I’m dreading this exercise.

“How’s that feel?” he says.

I shrug. “It’s just a pearl.” I don’t tell him that I’ve done this a lot. I’ve clutched uncooked beans, buttons, pennies. Anything smaller than a bead disappears from my senses, as if dropped into a pit.

With his eyes fixed on my face, he must see my discomfort, the unshed tears, and yet he pries my hand open and places his thumb on the pearl. He rolls it back and forth across my palm, pressing down. “Now?”

I nod. Yes, now I know the pearl is there.

Isaac makes me close my eyes. He lets me hold my pearl in one hand, as if for comfort, as he tries different items on my other hand, different temperatures and textures and sizes — his keys, the head of a pen, an electric toothbrush, a still warm teabag, a jagged little African statue the size of a finger that sits on his bed stand. He asks me questions about them, becoming more and more intimate as he moves through the items. Sometimes he kisses my cheek. “Do you feel that, Sara joon?” I can’t identify most of them. I sense a change between us and I want to be alone.

If one day an apocalypse comes and I find myself in a ravaged world, my body will have many scars. Who will I need to survive?

When he’s finished, I drop my single pearl on the couch and step over the pieces of my ruined necklace, shiny pebbles digging into the soles of my feet in a pleasurable way. I dress as Isaac watches, sad but without objection. Before I leave, he wraps his arms around my waist and I touch his lips, trying to memorize them, the way they roll and move as if on their own. We don’t say many words.

I type up every detail of the sex with Isaac. I am truthful and thorough, describing every cold brush of a toe, every twitch, every misplaced whimper. A full account is what’s needed here. I staple the pages together, for Arash, and stuff them into a hole left by an excised brick. I pretend I’m filling a surgical hole with fat. Afterwards, I’m overcome with the joy of a finished job. Fuck you, Arash.

I call Maman and let her talk and talk. I don’t tell her about Isaac. When she asks if I ever went out with him again, I say, “It didn’t work out.” She doesn’t press on, but I add, “We didn’t connect… on books, or music, or in very many words.”

“That’s a shame,” she says, probably raising that one wayward eyebrow she has. “Those things are important.” Later, she sends me an email.

Sara joon,

It seems so much trying and hurting and, like scraping yourself too raw. Why you don’t manage your time and focus as wise as you used to do while you were growing up? I always have big visions for you and I keep believing them.

Time for grieving is over, I think.

Your hands are capable! And finding love, is not finished. Is amazing that even in any age there is somebody out there to love you. You just have to be doing your works and love comes along, out of wood boards.

Also, come for abandoned walnut cake. I save for you, minus one slice.

Love, Maman

I melt away the lump in my throat with a shot of whiskey, delete the message and go to sleep. I dream about the calloused grip on the neck of a double bass, the finer points of neck surgery, a necklace of real pearls.

It takes half a day for me to discover that my nose is chapped from Isaac’s beard. I put on a ratty t-shirt and dirty jeans to Andy’s place because his furniture smells like old towels. Actually, that’s not quite enough — his furniture smells like old towels straight out of a Chinatown fish locker. I take my willingness to go there as a sign that we’ve become friends, and that I will keep him for a while. Maybe he can replace Kian, who, on hearing about my idea to go to Kabul, said, “Jesus, get a job.”

His words didn’t sting; Kian is Kian. After my accident, he changed my bandages every day until we left Tehran. Then he never spoke about it again.

I have to take three trains, but Andy lets us eat cheeseburgers in his bed, and he makes us the kind of drinks that sell for sixteen dollars at his bar. Afterward, I just want to cuddle and sleep and watch an old movie and definitely not get inside the sheets. But Andy starts with the belt fiddling, and the ear tasting, and I have to constantly pat his hands away while making a show of being transported by kissing him — because he’s my friend and it’s cruel to kiss like you’re feeding the hungry.

After a few more tries to undo my belt, he takes my face in his enormous, warm hand and says, “Sara. Do you not want to see me again?”

He slides his hand to my neck, rubs his thumb in a circle just under my chin, a gesture that confuses my body somehow. “Stop it,” I say, pulling away. “We’re not going to end up together. You’re not any kind of ‘it’ for me. Do you understand that? I’m here because I want to be here.”

“That makes no sense,” he says. He touches my nostril, frowning at the chapped edges. He mutters, almost to himself. “You never make sense.”

I push him away from my frayed nose, but he returns to it, roughly. “We’re not forever,” I repeat, at the same time as he says, “Stop that.”

Then we’re both silent, both trying harder to be kind. He says, “So what?” He looks at my palm, rubbing the spaces between my fingers like a mother cleaning her baby’s feet. “One day I’ll tell my grandkids that a beautiful writer with fucked up hands used to let me kiss her and hold her and try to be her missing sense of touch.”

“Don’t say that shit.” I try to smile.

He gets his guitar, arranges some pillows under my head and behind his back. He sits on the opposite corner of the bed from me, leaning against the headboard, and starts to play. The bed is a cheap kind with springs that creak and respond to movement like dominoes. As Andy plucks the strings the bed moves in rhythm, the motion wavelike. I close my eyes, letting the vibrations of his cheap mattress lull and soothe me. He whispers, “If I can turn you on without touching you once, will you believe it’s totally unimportant? Compared to seeing, hearing… it’s a damn useless sense.” I laugh and throw a pillow at him. He keeps picking chords.

“Shut up, Andy,” I mumble. He moves on to a playful tune, then a slow surging melody, and I imagine that I’m in a lifeboat far out in the ocean, that I’m creating this music in my delirium, conjuring it to match the rolling of the waves.

Then I am inside the guitar, in the hollow body of it, a part of the music again.

I think of my graceless hands, Andy’s generous, musical ones, and Isaac’s gifted, delicate ones — all the many fires and pinpricks and stabs and caresses I’ve felt through other people’s efforts. Even after my hands calloused over. And then later my heart. Isn’t it a marvel how many of life’s sensations start far beyond the skin? I conjure all the palms that I’ve touched, the ones that have touched me, in my travels: withered or stained ones, strong or trembling ones, kind ones.

I’m almost asleep, my arm over my face, when I feel Andy’s breath. The music has stopped and he’s lying beside me, pumping a small white bottle. “Hold still,” he says, as he dabs lotion on my nose. I squirm. “Get that thing away from me.”

“Shut up and hold still,” he says. He dabs lotion around the chapped edges of my nose, then above my lips and on each spot that a day ago Isaac must have grazed.

“Want a cigarette?” I ask. I imagine Kabul again, traveling far away and finding stories, stringing them together like beads, like scattered pearls on a floor. This isn’t a moment for a cigarette, but we smoke anyway, and drink sweet tea, our bodies hanging out of his window. I take the time to remember Arash. I summon him to my heart again. “Andy?” I mumble.

“Hmm?” he says, resting his head on the windowsill.

“If there was nuclear war, who do you think we’d need to rebuild the world?”

What I want to know is, if the world ended, would we be able to rebuild without Arash? Without his stories? How can the world manage and continue on? I want Andy to tell me that what we would need is a team of low-wage laborers and some city planners, and a few engineers, carpenters, doctors, and architects. Arash can’t answer distress calls anymore. So we won’t need him, right?

Andy runs two fingers through my hair and works out a snag. Then he kisses my earlobe, takes a drag, and blows a long curl of smoke out into the empty street.

My cabdriver plays a CD of classical music. In a Russian accent, he tells me we’re listening to the first movement of Brahms’s first piano trio, written by a man who spent his life longing. The melody is hypnotic, and as I lean back and try to enter it, the driver points out details. Here you can hear the cellist breathe before he runs the bow — dead for three years and, just listen… one of his countless breaths, preserved forever. And here you can make out the slap of horsehair on string, left in the raw recording like a fishbone in a clean filet.

We listen for ten minutes and the driver relaxes as I’m drawn in. He claims to have spent time at the Paris conservatory. Fingers trained to play Rachmaninoff now turn the wheel toward my apartment on Essex Street. He seems perpetually delighted. Near the end, he offers to replay the part with the cellist’s faint breath…

He fumbles with the buttons on his external CD player, an old clunky thing.

In the backseat, I’m stricken. I remember the thing that drove Arash to dig for stories, the thing he searched for in his travels, in our travels — the whine of sitting-room poetry, two overplucked strings beside two broken ones, the last joyful noise in a crush of wailing. I can’t wait to get home. My fingers itch with a kind of purpose, for work, for solitude. Maybe it’s time to rouse my other senses. When I write about today for Arash’s wall, I will tell him about this middle-aged cab driver, with his uneven swirl of thinning blond hair, grinning as he turned back in his seat again and again. How he marveled, “You can hear the man’s breath.”