interviews

‘A Good Writer Has to Walk the Earth and Take Notes’

James McBride on learning not to judge his characters, imagining the inner lives of animals, and touring with the Jacksons

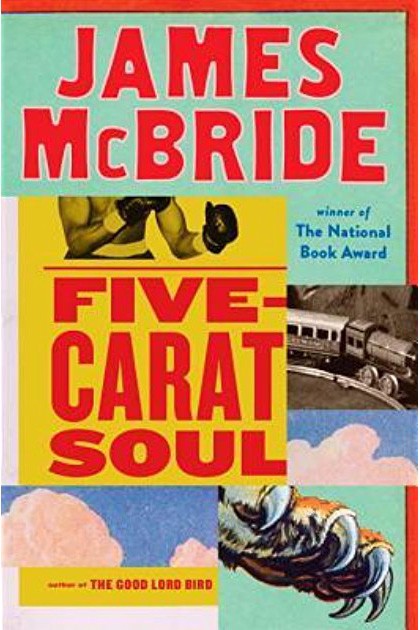

National Book Award winner James McBride has assembled a broad cast of characters, stretching over 150 years, for his new book of short stories Five-Carat Soul. (A story from this collection, “Buck Boy,” was published in Recommended Reading in September.) Poignant and painful, comedic and cutting, McBride’s collection covers the larger themes of race and humanity through riveting, intimate, uniquely-told tales. During the Civil War era, Abraham Lincoln gets an undercover lesson on race by observing his stable-hands. In an unrelated story, “Father Abe,” a mixed-race orphan believes he is Lincoln’s son. “The Under Graham Railroad Box Car Set” spans the past and present as a white antique toy dealer traces an almost priceless 19th-century train set to the home of a poor Black preacher in modern day New York. “The Moaning Bench” is set at the doors of Hell as an unlikely cast of characters, led by a boxer who resembles Muhammad Ali, wrestle themselves from the grasp of old Beelzebub himself.

McBride’s originality is in part due to the experiences he’s lived. He was a staff writer for the Boston Globe, People, and The Washington Post before he quit journalism to be a full-time musician, writing songs for Anita Baker and Grover Washington, Jr. among others. But McBride would find his steadiest recognition through his books and stories. His memoir The Color of Water, about growing up in a poor Black family whose matriarch was a white Jewish mother, was on the New York Times bestseller list for two years, and his 2002 novel Miracle at St. Anna was made into a movie by Spike Lee. His last work, The Good Lord Bird, won the National Book Award for fiction in 2013. Five-Carat Soul joins the ranks of an already strong artistic catalog for McBride.

Jeff Vasishta: Had you been writing these stories over a very long period of time or did they arrive to you fairly quickly?

James McBride: I wrote them over the years. Some were written years ago when I was in my 20s. The lion story I wrote while I was a reporter at The Washington Post back in the ‘80s.

JV: History plays a big part in many of these stories, both recent and older. “Under the Graham Railroad Box Car Set” is fascinating. It works so well telling it from the viewpoint of the white antique dealer. Where did that story come from?

JM: I don’t know… it was in the air. I used to know a toy collector, and I was amazed that in a world where millions of children go to bed hungry every night, people pay enormous sums for old toys. But the toys are simply the vehicle in the story to get those two characters, the toy collector and the preacher, moving. Good stories should have characters that connect. We all connect in life, by accident, or God’s will, or by karma. Once that happens, it’s the writer’s job to show how these connections and histories intertwine, or don’t. Those connections, or missed connections, are what makes the world spin.

JV: Race relations are an underlying theme in many of your stories. In the previously mentioned one, both the dealer and the box car owner think of the other with a certain amount of incredulity. Just so I’m clear, does the Reverend know the value of the toy all along? Was he playing the antiques dealer?

JM: I can’t answer that easily. The Reverend is himself, to me. He’s a real living thing in my mind. I don’t think he really cares about the value of the toy. I think he cares only about his second life, which expresses the rage that his first life cannot. He was not trying to con the antiques dealer. If you think like that, by the way — hustle, con, etc.— you can’t be a good writer. It destroys your creativity. Writing requires innocence. If there is judgment, there is no journey.

Writing requires innocence. If there is judgment, there is no journey.

JV: You grew up in Red Hook, Brooklyn and went to school at Oberlin and the stories set in Uniontown, Pennsylvania, like “Ray-Ray’s Picture Book” and “Blub” have real resonance. Why choose Uniontown during the 70s? Did you think they would have a different, smaller town, blue collar feel than if you set them in Brooklyn?

JM: My brother-in-law grew up in Edenborn, Pennsylvania. He’s a doctor now. I enjoyed his talks about growing up in that town. That town also produced C. Vivian Stringer, the coach of the Rutgers women’s basketball team. It seemed a good place to put these characters. I’m a little worn out with stories that continually depict African American characters in city landscapes with chain link fences and basketball hoops. Similarly, I’m done with the usual stereotypical versions of working-class white characters who howl to the moon, drink beer, and shoot pistols. Americans are dynamic and varied. It doesn’t matter that the stories take place there, in a way. The feelings are the same. The story is the same everywhere. Kids are the same the world over.

JV: I found “The Moaning Bench” very moving. And has direct parallels to Muhammad Ali. Why did you chose to give him another name?

JM: Nobody is Ali. Rachman Babatunde has to be himself on the page, otherwise it really becomes Ali, and then it’s not my character, but rather Ali himself, and you cannot create someone on the page as strong as Ali was. In fiction, you are just borrowing humanity. I met the real Ali at his training camp once when I covered him as a young reporter. I will never forget his kindness. I wanted to pay tribute to him — and to Joe Frazier — without cheapening what they meant to those of us who respected them. That story tries to show what Ali meant when he said “I am the greatest.” He was really speaking to all of us, showing us where our own greatness lies. He was a wonderful man, a wonderful Muslim; one of the greatest figures this country has ever seen.

JV: “Mr. P & the Wind,” is mind-blowing, literally. The concept — animals speaking to each other in Thought-Speak — humanizes them. When writing the animals voices in such a way did you have cultural distinctions in mind?

JM: Not really. The lion’s voice is strong, and he’s Black, and it helps to have a strong Black character who is not saying “shit” and “fuck” all the time. The other characters are just… who they are with attendant issues. Rubs for example is a female gorilla who has all the issues, or some of the issues, of any older woman. If you start splitting hairs about characters, you’ll really be screwed up. You can’t approach a story and say “I’ll write the Black perspective.” There is only one perspective. The human one. That helps keep your characters fresh. Writing about animals as humans was refreshing. Animals have no prejudice. The only prejudice in that story, I’m sorry to say, is mine.

JV: There is twist in many of the tales. I’m never quite sure how they are going to end. Did you try out alternate endings for many?

JM: No. The stories end where they will end. In fiction, you’re getting out the way of the story. Just wave the cape and let the bull pass, then run out the arena before he catches his breath and turns around. Get out. You’ve had your fun.

The stories end where they will end. In fiction, you’re getting out the way of the story.

JV: You’ve had a varied creative career — journalist, musician and fiction writer. Which has been the most enjoyable or the least stressful?

JM: Writing is hard because it requires a lot of research. But it’s less stressful than music. Music is more enjoyable but much harder overall. Nobody respects musicians, really. Everyone is paid so poorly, except maybe Hollywood composers. And serious Black musicians are at the lowest end of the totem pole. There is no one group in American artistic life who bear the burden of racism implicit in history and culture than serious Black musicians.

JV: I actually knew of you first as a musician and songwriter. I used to be an editor for Blues & Soul Magazine and I have the CDs you wrote songs on. So realizing literary James McBride and the musical one were one and the same was quite a shock. The paths of jazz musicians and literary figures don’t usually intersect. Do you ever wake up in the morning and say, “Do I want to write songs or write fiction today?”

JM: No. That time is past, but you bring up good memories. I loved writing for Anita Baker. She gave me my first break. Grover Washington was a music pioneer who never got credit for starting “smooth jazz.” I was starving in those days. When Anita recorded that first song. “Good Enough” and I got paid — and it took so long for that dough to come — I went to the bank, got out $500 in singles and threw them across my bed. But then I had to pick them all up. I was young. I was living in Fort Greene, Brooklyn back then. This was the ‘80s. In those days Brooklyn was a forgotten country. It was so much fun. But that time has past. My job now is to make a way for others, just like Grover and Anita and Little Jimmy Scott did for me.

A Black Man’s Murder Tears Apart a Town

JV: How did winning the National Book Award change your career, if at all?

JM: I think the award verified that I can write fiction on a high level, and I thank God for it. But in this world, you’re only as good as your last book.

JV: Many people don’t know that you were on the Victory Tour with the Jacksons for 6 months when you were writing for People, which I guess brought together many of your worlds. If you had to name one thing from being a musician and journalist that had the most effect on fiction what would it be?

JM: A good writer has to walk the earth and take notes. That’s the first thing. And Hollywood is not a place to pursue happiness. That’s the second thing. A writer has to do every job that comes, as hard as they can, as long as they can stand it. The jobs and hustles and struggles you endure are bank books that you draw on later. They’re emotional savings accounts that draw interest so long as you don’t let the bitterness of failure cloud your vision and soil your innocence. That tour was difficult for me. Other than meeting Michael Jackson’s mother — Mrs. Katherine was a special person, a wonderful person — I hated that tour. I hated what went on. I felt the Jacksons were exploited and misunderstood. The fact is, I’m just not a Hollywood kind of cat. But I learned a lot about humanity, and met some nice people, and learned why money isn’t the most important thing in the world. I spent a lot of time in my hotel room practicing my horn and writing fiction. I put myself in God’s hands and He led me through.