essays

A Hypertext Tribute to James Tate (1943–2015)

James Tate was one of our most celebrated and prolific writers, with over twenty collections of poetry, several works of prose, and awards ranging from the Yale Series of Younger Poets Prize and the Wallace Stevens Award to the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. And he yet had good humor to spare.

Here, some of Tate’s fellow poets, former students, and friends remember the man and his work, in their own ways and in their own words. Scrolling over the image below will introduce you to some of the poet’s most memorable lines; clicking on those lines will bring you to the full text of each poem. Once there, you will notice links within each poem. These links offer personal memories of Tate, commentary about his work, and recordings of some of his most meaningful poems.

As Tate himself said, in “The Initiation,” “The piece is dedicated/ to me. How strange,/ I thought I was new here.”

Technical note: To experience the interactive features of this interview fully, please turn on your device’s audio.

If this trick works we can rub our hands

together, maybe start a little fire…

[Dear Reader] Truth is, you are

free, and what might happen to you today, nobody knows…

[Saint John of the Cross in Prison]

Jesus got up one day a little later than usual…

×

Dear Reader

I am trying to pry open your casket

with this burning snowflake.

I’ll give up my sleep for you.

This freezing sleet keeps coming down

and I can barely see.

If this trick works we can rub our hands

together, maybe

start a little fire

with our identification papers.

I don’t know but I keep working, working

half hating you,

half eaten by the moon.

[The Oblivion Ha Ha, 1970]

Close

×

Consumed

Why should you believe in magic,

pretend an interest in astrology

or the tarot? Truth is, you are

free, and what might happen to you

today, nobody knows. And your

personality may undergo a radical

transformation in the next half

hour. So it goes. You are consumed

by your faith in justice, your

hope for a better day, the rightness

of fate, the dreams, the lies,

the taunts. — Nobody gets what he

wants. A dark star passes through

you on your way home from

the grocery: never again are you

the same — an experience which is

impossible to forget, impossible

to share. The longing to be pure

is over. You are the stranger

who gets stranger by the hour.

[The Oblivion Ha Ha, 1970]

Close

×

Saint John of the Cross in Prison

Browsing among the zero hours,

and where I went from there . . .

diabolical? No. I went out

of myself into . . . I did not go

out of myself into the after-

noon of parrots; I did not go out

of myself into the dew; I did

not go out of myself into the

bat-terrors. I did not say silence,

I said nothing about the love I

did not go out of myself into.

I said nothing fire, I said nothing

water, I said nothing air. I went

out of myself into no, into

nowhere. I was not alone.

[Absences, 1972]

Close

×

Goodtime Jesus

Jesus got up one day a little later than usual. He had been dreaming so deep there was nothing left in his head. What was it? A nightmare, dead bodies walking all around him, eyes rolled back, skin falling off. But he wasn’t afraid of that. It was a beautiful day. How ’bout some coffee? Don’t mind if I do. Take a little ride on my donkey, I love that donkey. Hell, I love everybody.

[Riven Doggeries, 1979]

Close

×

Amy Newman

James Tate has said his autobiographical work is “based on a little truth and a lot of myth, or a lot of imagination.” Any writer interested in how the materials of life alchemize in poetry may consider his early poem ‘The Lost Pilot.” How deftly Tate navigates between what is real (a son’s desire to reunite with the lost father) and what he imagines (Tate would never know his father, who was shot down in WWII when Tate was an infant). In the poem, what is unseen by the human eye remains the most vivid of images. The son’s imagined father navigates both the sky and the son’s psyche, distant and ever-present and, in his absence, perfected to a god. The speaker tries, impossibly, to romance him back to the world with promises:

If I could cajole

you to come back for an evening,

down from your compulsive

orbiting, I would touch you,

read your face as Dallas,

your hoodlum gunner, now,

with the blistered eyes, reads

his braille editions. I would

touch your face as a disinterested

scholar touches an original page.

In such a gaze, in his desire to know the lost one who is dreamed of, longed for, and also feared, Tate’s speaker conjures the capacity for dread mingled with reverence that is the definition of awe.

Close

×

Sarah Blake

What I would call my first poetic voice came out of my love for James Tate, Mark Strand, and the prose poems of Charles Simic — three men who valued humor, image, action, and the absurd — men who prioritized the turns of language over the fluff of it. Every time I’m asked about my use of language in my own poems, I return to these men in my head. I think about tension, how a sentence pulls itself over the lines, how juxtaposition and pace work to elevate, work to surprise. Looking back, it surprises me that I started with these men, but I’m so glad I did. Because of them, I never felt unusual.

From “It Happens Like This,” by James Tate

I was outside St. Cecelia’s Rectory

smoking a cigarette when a goat appeared beside me.

It was mostly black and white, with a little reddish

brown here and there. When I started to walk away,

it followed. I was amused and delighted, but wondered

what the laws were on this kind of thing. There’s

a leash law for dogs, but what about goats? People

smiled at me and admired the goat. “It’s not my goat,”

I explained. “It’s the town’s goat. I’m just taking

my turn caring for it.” “I didn’t know we had a goat,”

one of them said. “I wonder when my turn is.” “Soon,”

I said. “Be patient. Your time is coming.” The goat

stayed by my side. It stopped when I stopped. It looked

up at me and I stared into its eyes. I felt he knew

everything essential about me. We walked on. A police-

man on his beat looked us over. “That’s a mighty

fine goat you got there,” he said, stopping to admire.

“It’s the town’s goat,” I said. “His family goes back

three-hundred years with us,” I said, “from the beginning.”

The officer leaned forward to touch him, then stopped

and looked up at me. “Mind if I pat him?” he asked.

“Touching this goat will change your life,” I said.

“It’s your decision.” He thought real hard for a minute,

and then stood up and said, “What’s his name?” “He’s

called the Prince of Peace,” I said. “God! This town

is like a fairy tale. Everywhere you turn there’s mystery

and wonder. And I’m just a child playing cops and robbers

forever. Please forgive me if I cry.” “We forgive you,

Officer,” I said. “And we understand why you, more than

anybody, should never touch the Prince.” The goat and

I walked on. It was getting dark and we were beginning

to wonder where we would spend the night.

From Lost River by James Tate, published by Sarabande Books, Inc. Copyright © 2003 by James Tate.

From “The Tunnel,” by Mark Strand

I destroy the living

room furniture to prove

I own nothing of value.

From “The World Doesn’t End,” by Charles Simic (dedicated to James Tate)

A dog with a soul, you’ve got that? You apes with heads of Socrates, false priests’ altar boys, retired professors of evil! I imagine cities so I can get lost in them. I meet other dogs with souls when I’m not lighting firecrackers in heads that are about to doze off.

Blood-and-guts firecrackers. In the dark to see, you ass-scratchers! In the dark to see.

Next

Close

×

Jill McDonough

I think this is a good one about poetry and faith, and trying to write something for strangers. Maybe even strangers who’ll read and love your work after you’re dead.

Look at all this poem’s tricks: burn snowflakes? Check. Open caskets, bringing the previously-only-imagined reader to life? Boom. End up both ecstatic and irritated? Sounds right.

Say we are the reader, wedged into a sudden aliveness with the writer. He’s willing to give up sleep to make us real, driving toward us all night in the sleet. It’s cold out there with the firmament and waters, lost in the coalescing matter making up this world. Let there be light, “a little fire.” Okay.

Then we are together, just us and Tate, all in, burning our identification papers for warmth. Who needs them? Who needs them once the poem is working, and we’re met there together? He doesn’t know. We don’t know. But here’s a poem about him tunneling toward us, working on faith, bringing us to life.

Close

×

Fady Joudah

I insist on return: I return you to me, you return me to you, or me to me and you to you: return is only to the stranger.

These lines came to me after I spent some time reading or rereading Tate’s earlier poems — before he fatigued from a certain form, and his mind and body fatigued along, before he went into the prose format and its allegorical inner world, its own semi-private logic that was always announcing the final disintegration, a return to being a root….dear James:

Close

×

Dorothea Lasky

“People read poems like newspapers, look at paintings as though they were excavations in the City Center, listen to music as if it were rush hour condensed. They don’t even know who’s invaded whom, what’s going to be built there (when, if ever). They get home. That’s all that matters to them. They get home. They get home alive.”

It’s true. Some people do and can have a tendency to read poems as if they are these things they can safely enter and leave at will. They want a sad poem to make you sniffle a little but not wail. They want a funny poem to make you say, “Ah, how clever,” but not belly laugh. They want a poem about sex to be erotic, but they don’t want to think about fucking towards an inevitable death. Tate knew that a poem will never let you have the will to do anything, except be. Because once you’re in a poem, you had better be ready to be changed — you will never get home alive no matter how much you claw back towards there. In a poem, home is already gone and you’re already a new person, ready to live a new life, do new things, make the world new again.

But in these past few days, I haven’t read this favorite poem as much, instead I have read this poem over and over, “Very Late, but Not Too Late.” I am not sure why I have focused on this one particularly, but it does represent particularly what Tate has taught us. In the poem, the speaker feels empty, but then he finds a purpose: this lonely woman who he can save or maybe she can save him. It’s a romantic/Romantic poem. Because it states that within the act of the journey there is always hope. Because it somehow insanely believes that even though (to quote my best friend) evil always wins, underneath this reality is the idea that life can start again, that a life has only begun on a night road traveled already so many times, that as my grandmother used to tell my mother “love is always right around the corner,” that we are never too late for a new beginning. These are good things to think about. Without these considerations, what is life.

James Tate was my teacher and he gave me immeasurable lessons both in and outside of the classroom, both in and outside the space of the poem. The past few days I have been remembering his feedback in class and how much he loved using the word, wild. When he used that word about your poem, you knew you had done something right. I remember distinctly the first time he used it on my poem. I had included the image of an ostrich and for some reason, he commented, just kind of matter-of-factly, “Wow, that’s pretty wild.” All the accolades of my nerdy youth fell away in that moment. Now this is what I want a poem to do, I thought. It’s a test I give myself with my work every day. Is this idea really wild, I ask myself. It’s a good question, because if you aren’t thinking about the wild in your work, if you are keeping your language and ideas purring methodically, then you aren’t really doing the right work at all. I mean, really, if the poem isn’t strong enough to bite you, then what’s the point.

It makes sense that the wild would have been important to his feedback, because his poems were certainly so. But it’s not as if they were all ragged edges and off beat staccato rhythm. He was an expert at regulated beat, his lines were perfectly constructed and paced. No it’s more that he was willing to let nihilism coexist with sincerity, to let his persona express the disagreement we all feel with ourselves and others. Not disagreement like there is one right answer, more that we will never come to a consensus about anything. We won’t ever really understand why we are here, what the point of our lives is, or if we were meant to meet the woman alone at night or if it were a random occurrence (a law of life that is one and the same). To be truly wild means to in spite of it all really believe that it’s never too late for life to begin. I don’t know about you, but I don’t want to ever forget that.

Last summer, I had the honor of teaching at the Juniper Summer Writing Institute and one of the days I went to a conversation between Dara Wier and James Tate. I wrote down so many things that Tate said, but one thing I have kept remembering all year is when he said, “I never know what is coming next. And that is the excitement of writing. And that is what keeps me glued to the poem.” It’s stuck with me because it really sums up what’s magical about creativity. I hope to always write and read poems where I can’t anticipate what’s coming next. And I hope in this life, when I am traveling the winding road full of dirt and bugs and people and trees, there is the answer to all my hopes and fears, just waiting there, ready to start me up again. If we can manage to live for this, then we can manage to live for anything.

Thank you, James Tate, for everything.

Close

×

Eduardo C. Corral

James Tate ruled the MFA program at Arizona State University in the late 90s. It seemed every poet in the program read him passionately. I was an interloper, an undergraduate student who’d just discovered poetry. I attended all the readings, I studied all the posters hung along the hallways of the English department, I crashed graduate-level workshops. In other words, I was a pest. The MFA students were, for the most part, kind to me. Some of the students could barely hide their dislike for me. I ignored those students. Instead, I reached out to the welcoming ones, the ones who remembered the fever, who remembered the thrill and anxiety of falling in love with poetry.

I was a nervous wreck among the MFA students. They were so worldly and so well-read. I was just starting out. I made it a point to ask each student to recommend a few books. Without fail, each student would mention one of James Tate’s books: The Worshipful Company of Fletchers, The Lost Pilot, and Distance from Loved Ones. Though each time I went to the library, I couldn’t locate his books. They were either checked out, misplaced, or stolen. One day I ran into Brandon Som on the first floor of the library. Brandon was an undergraduate student and a budding poet, like me. I noticed he was returning The Lost Pilot. After a few minutes of small talk, we walked to the circulation desk. He returned the book. I checked it out.

The poems in The Lost Pilot rattled me. Let me be more specific: the attitude of the speaker toward his parents rattled me. In the title poem the speaker says, “Your face did not rot.” In the poem “For Mother on Father’s Day,” the speaker confesses to his mother that he pitied her. These were instructive and challenging moments for me as a fledgling poet.

They forced me to rethink the way I wrote about my parents. My early poems viewed the familial through rose-colored glasses. My mother was a saint. My father was stoic, pure. The poems in The Lost Pilot showed me it was okay for a son to express anger, doubt, ambivalence, and a host of other emotions. James Tate was one of the poets who taught me a poem could be as complex as love.

Close

×

Brian Henry

Many of James Tate’s poems, particularly those from the past 20 years, enact mini-fictions in which he is generally the protagonist. By rendering the poetic fictive, Tate becomes both character and narrator as well as author. And he combines this narrative line (which frequently approaches the nonsensical, the hilarious, the enigmatic, and the profane) with both a prose vernacular and the kind of linguistic facility evident in his poems from the beginning. As with William Carlos Williams, his work attains the measure of speech without becoming prosaic or merely garrulous. And his use of dialogue seems reminiscent of the dialogue in Grimm’s fairy tales (at least as translated by Jack Zipes). Tate’s poems since Memoir of the Hawk and the fairy tale share more than absurdist, deadpan, economical dialogue: consider how the impossible is presented as absolutely normal, how the mundanity of violence is portrayed, how language both saves and fails.

Close

×

Joe Pan

We’ve all had those nights. It’s two or three AM, something has triggered an abrupt end to the seemingly banal reverie you’ve been inhabiting, & you look around to notice everything has gone still, hushed, & you are alone with yourself, more alone than usual. Your living room undergoes a subtle shift, in light, in balance. You are hyperconscious, almost predatory with your senses, & it all comes into relief — the wood of the bookshelves find their edges; objects slough off whatever personal meaning you’ve attached to them; & it’s like a film has slipped from the framing of your life as the dreamlike quality of your narrative expires & awaits reset, the true nature of your bodily existence now disinterred, & you find yourself imbued with the awful clarity of mortality. You are nothing more or less than an obvious statement of fact, an example — of the universe practicing consciousness, perhaps — & unless you are a Buddhist of the most devout practice, experience an overwhelming sense of dread. Strangely, though, a deep acceptance begins moving through you, hollowing new channels, until you arrive at a leveling, tired sadness that accompanies what feels like some ultimate spiritual acquiescence.

It is sobering. God help you if you have a child or partner sleeping on the couch. The curves & heft of my wife’s body transubstantiate to become the actual physical embodiment of loss & suffering, like during a lunar eclipse, when the moon sheds whatever poetic frivolity ascribed to it & greets you undressed as the floating orb it is, so close in its insurmountable distance that what lies beyond it, that anything could lie beyond it, seems impossible, induces panic.

The Germans must have some throaty word for this, something molecular & crushing. When Don DeLillo was asked by a friend what he should do to stave off this particular fear, the elder writer responded: “Watch more television.” Because cognitive distraction is not only how we’re able to drive a car while ruminating on our day’s to-do list, but also why we can shop for food at the grocery store without huddling crouched & weeping under the fruit table. Our brains must remind themselves not to be constantly reminded of certain facts. Entertainment is a readily available nostrum. In moderate doses, we are briefly relieved of ourselves & our problems. In large doses we forget our humanity, forget the suffering of others, forget our responsibilities to the political moment. But then, death. How are we supposed to combat daily reminders of the erasure of the self while retaining compassion & a belief in the meaningfulness of our actions?

The Private Intrigue of Melancholy

Hotels, hospitals, jails

are homes in yourself you return to

as some do to Garbo movies.

Cities become personal,

particular buildings and addresses:

fallen down every staircase

someone lies dead.

Then the music from windows

writes a lovenote-summons on the air.

And you’re infested with angels!

This James Tate poem shows our insides for what they often are — returned-to waiting areas — while simultaneously performing what I love most about his work, that it can hold in its ephemeral hands both the struggles & the joys of life. The poem accounts for the sorrow, for the dead, for the forgetting, for the reemergence of ecstasy. It is entertaining, but also active, invested, & if you’re someone searching, instructive. In the darker periods of my life, Tate’s poems have become a welcomed infestation. In those moments of haunting self-discovery, in that essential aloneness, Tate’s humor can help hunt down what Rilke called the “the unity of dread and bliss” in order that we might “[take] possession of the full, ineffable power of our existence.”

The thing about anxiety over this kind of insufferable impermanence is that the feeling passes. The filmic nature of our narrative-inducing brains lays a fine layer of plastic over everything again, if only for a short while, & we’re back to being profoundly ignorant of our own impending deaths. Thank god for forgetfulness. But somewhere in our subconscious the feeling persists, & it’s nice, for some weird reason, to be reminded of the fact, so that we might laugh it off. This is where Tate’s poems really get going, for he was a master of macabre humor.

The Lack of Good Qualities

Granny sat drinking a bourbon and branch water

by the picture window. It was early evening and she

had finished the dinner dishes and put them away and

now it was her time to do as she pleased. “All my

children are going to hell, and my grandchildren, too,”

she said to me, one of her children. She took a long

slug of her drink and sighed. One of her eyes was all

washed out, the result of some kind of dueling accident

in her youth. That and the three black hairs on her

chin which she refused to cut kept the grandchildren

at a certain distance. “Be a sweetheart and get me

another drink, would you, darling?” I make her a really

strong one. “I miss the War, I really do. But your

granddaddy was such a miserable little chickenshit he

managed to come back alive. Can you imagine that? And

him wearing all those medals, what a joke! And so I

had to kill him, I had no choice. I poisoned the son

of a bitch and got away with it. And so I ask you, who’s

the real hero?” “You are, Granny,” I said, knowing I was

going to hell if only to watch her turn to stone.

All humor is gallows humor, in a certain light; the heart of comedy is vulnerability. On a larger scale, the absurdity of the sublime arrives when we recognize that, trapped in the commanding breadth of its field, we are exposed as neither important nor unimportant, & that’s pretty funny, in a very tragic sort of way. Our laughter is the reaction to some true part of us being exposed. Humor makes light of important things, or makes seemingly inconsequential things suddenly important. It’s absurd that a tomato in a joke can become, though language, the absolute saddest thing on the planet for a moment. We chuckle. That release is possibly our grandest gesture of human vocalization. It’s contagious & provocative & social, & cuts through us like no words can.

Another thing literature can do is serve as mile markers, becoming intractable from the memory of a defining moment or era. As a young man who escaped the book-burning, gay-bashing, othering wilds of Florida & my Southern Baptist roots, this poem — the first I ever read of Tate’s — sent me back giddily on my heels:

Goodtime Jesus

Jesus got up one day a little later than usual. He had been dreaming so deep there was nothing left in his head. What was it? A nightmare, dead bodies walking all around him, eyes rolled back, skin falling off. But he wasn’t afraid of that. It was a beautiful day. How ‘bout some coffee? Don’t mind if I do. Take a little ride on my donkey, I love that donkey. Hell, I love everybody.

From the writer & humorist Finley Dunne — or H.L. Mencken, depending on who you ask — & delivered slightly altered by Gene Kelly in Inherit the Wind: “[It] is the duty of a newspaper to comfort the afflicted and afflict the comfortable.” The same thing can be said about literature — & has been.

In his seventy-one years, James Tate has afflicted & comforted many a poet, I’m sure.

Being funny is hard work. Living in all this pain & fear is hard work too. Camus said that we must believe that after all the hard work he did rolling his boulder up the hill, only to watch it fall back down, Sisyphus somehow managed to stay happy. & Sisyphus was happy, because the work of struggling in our humanness matters to us. We find unity in it. & besides, who doesn’t like to watch a boulder roll down a hill?

Close

×

Matthew Zapruder

I’ve been trying to write this little tribute to Jim for days. Every time I sit down to do it, I pick up one of his books, and just want to read, and also think about the many years I knew him, first as his student and then as the recipient of his gentle friendship, and also as a witness to his life as a true poet.

I had wanted to write something about “The Blue Booby,” one of my favorite poems by Jim. It’s an early poem, from his second book, which has the best title ever, The Oblivion Ha-Ha. I love the way the poem moves from actual information about the birds into unselfconscious projection and personification. It’s goofy and sweet, and also the end of the poem has always seemed scary and distant to me, the way the stars reflected in the blue foil are like the eyes of a “mild savior.” Those many eyes seem perfectly spooky and creepy and sublime, like we are being watched over by a giant beast, which probably we are. I asked my mom, when she was traveling down to the Galapagos a few years ago, to read the poem to the Blue Boobys, which she did, and then she brought back from there a piece of blue fabric that she sent to me and I brought to Jim in his house full of stacks of books and marvelous objects.

On my desk is the blue and white and black Selected Poems I bought at Cody’s Books in Berkeley, when I knew I was going to come to the MFA program at UMass Amherst to study with Jim. It became my constant companion. Now I am looking at my brown paperback of Distance from Loved Ones, which I bought as soon as I arrived in Amherst. “Quabbin Reservoir” is about the body of water created by a dam in the 1930’s, that covered over four small towns (don’t worry, the people were moved out first). It begins

All morning, skipping stones on the creamy lake,

I thought I heard a lute being played, high up,

in the birch trees, or a faun speaking French

with a Brooklyn accent. A snowy owl watched me

with half-closed eyes. “What have you done for me

philately,” I wanted to ask it, licking the air.

There was a village at the bottom of the lake,

and I could just make out the old postoffice,

and, occasionally, when the light struck it just right,

I glimpsed several mailmen swimming in or out of it,

letters and packages escaping randomly, 1938, 1937,

it didn’t matter to them any longer. Void.

No such address.

and then goes on. Talking to the owl, wanting to ask it, what have you done for me philately, that impossibly clever and naughty triple pun (lately, philately, fellately), the village under the lake with its mailmen still delivering lost packages. I knew I was in the right place when I read that poem. My friends and I learned more reading his poems and just being around him when he talked about poetry, and also knowing how he and Dara Wier worked, than we could easily absorb. While I was [at UMass Amherst] as a student he published Worshipful Company of Fletchers in 1994. Many of us remember being at a reading at tiny Wooton’s Books on the main street of Amherst for the release of that book: it was the single most antic, hilarious, heartbreaking, electric reading I have ever been to. There was a sense of being right in the middle of poetry. Our coffins had been pried open by the burning snowflake, and now we were alive.

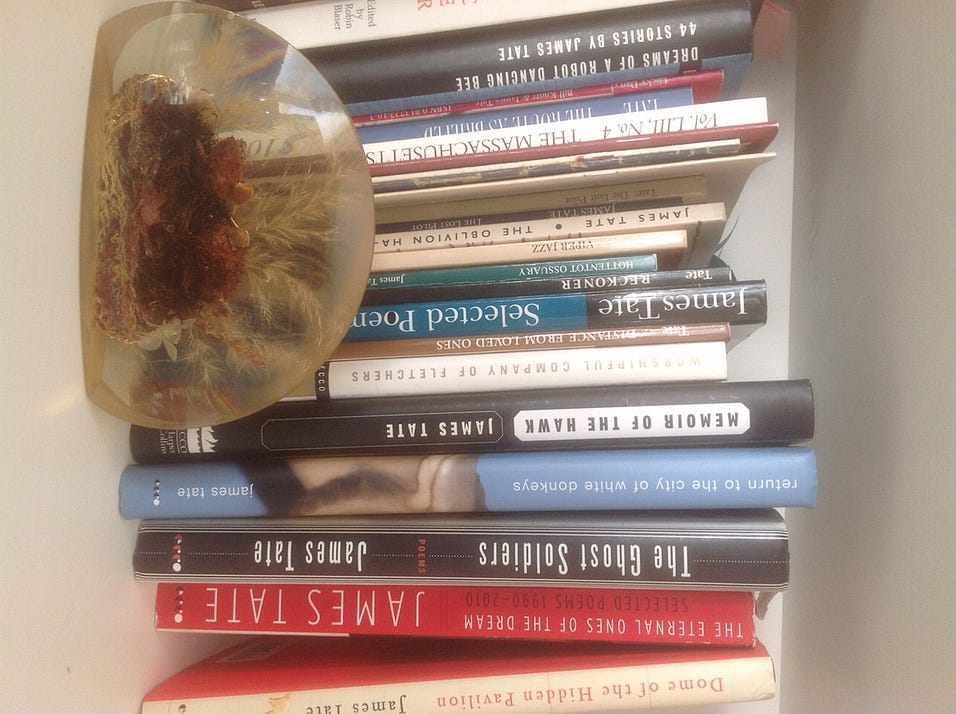

I can’t find my copy anywhere of maybe my favorite of his books, Shroud of the Gnome. Maybe I lent it to someone, a student. If so I hope they are reading it. Memoir of the Hawk has one of my favorites of Jim’s poems, the first one I read after I found out he had passed away, “Rapture,” with its blue antelopes. Return to the City of White Donkeys, The Ghost Soldiers, and the second volume of his selected poems, The Eternal Ones of the Dream, are right next to me too. And yesterday in the mail I just received his final volume, Dome of the Hidden Pavilion (no one will ever write better book titles). I just read the last poem in the book, “Plastic Story.” In it, he wrangles with a piece of plastic, tries to push it under a chair, because “Some things are not worth contemplating.” Eventually he goes to sleep and imagines he’s being strangled, and then discovers he is. “A piece of plastic had grabbed my throat and was strangling me./ I fought with all my might, but it was too late. I had never/ done a thing to hurt that plastic.” I can hear Jim saying it, like he’s here in the room. It’s not online, you’ll have to get the book to read it. Please do. And then get all his other books and read them too. You’ll be so happy and sad and grateful, like I am now.

Close

×

Gail Mazur

“The Lost Pilot,” by James Tate

Close

×

Adam Fitzgerald

James Tate is one of the greatest originals that American poetry has ever produced. Upon learning of his passing, my heart has remained full and sad because I know that for many in Amherst, and throughout this country, his family, many friends, as well as a massive network of former students throughout the years of his legendary teaching, he was their one true genie. He was also, it bears emphasizing, one hell of a sweet man.

Because Tate’s career was so long and prolific, so inexhaustibly inventive and imaginative, there will be many books to revisit and favorite poems to remember. For me, it will be the prose poetry of the last two decades, in particular Ghost Soldiers, where I felt he entered (and perfected) a zone of literary space only James Tate ever, and ever will have, entered. Not that his work is without its familiars — especially the wacky flash-sized prose worlds of Borges and Kafka.

As a creative writing teacher these last five years, I remind myself now and then of something David Foster Wallace once said on Charlie Rose’s program. That teachers — perhaps he meant especially writer/teachers, just like himself? — tend to burn out after a few years. Many an adjunct knows firsthand that the temptation to repeat sometimes overwhelms the desire to improvise. Yet there’s also a special kind of wisdom that only comes once you’ve taught certain texts for ten or twelve semesters straight, as I’ve done with but a few trusty authors in my classes of introductory creative writing. One of these wisdoms I cherish is that no matter the classroom, the university, the pedigree or limited interests of my students, I can — and have! — always relied on a packet of Tate’s prose poems early on in the semester to energize and awaken young writers to the joy of reading. This is, I suppose, because writing, whatever else it may be primally tied to, is about freedom. Freedom from obvious and bad choices; freedom to make new and surprising ones; freedom to reproduce reality, your own private world or the big unknowable one as you see it around you. And of course, writing is also about freedom to let things fuck up, spoil, break in half, collide and mutate. When I read “The Cowboy” or “Uneasy About the Sounds of Some Night-Wandering Animal,” that’s what I’m continually reminded about, the harrowing fertility of Tate’s genius.

So yeah that’s what James Tate means to me as a writer, reader, teacher. FREEDOM. It’s a word he would snicker at, I imagine, rightfully, since no poet demonstrated better than him how hollow and macabre our national pride is/was, its charming and combustible myths. He also captured our persistent small town paranoia, Main Street’s wry hubbub, workplace as absurdist purgatory. But the poems, like him, had a sweetness of spirit that always carried us through, you know, straight on through to the next lovable and treacherous bend in the road.

A few years ago, I did an interview with Jim that yielded a 20-plus-page document, which remains unpublished. From it:

Did you ever wonder to yourself, where did this all brilliant, mad poetry come from? Maybe someone far back in your family tree had a way with words, too?

James Tate: No, no, absolutely not. Nobody. I can almost remember when it clicked in my head. I was 17 at the time and I just left a very rich high school in which I was part of a pretty large gang, as we called ourselves. It was very social and fun; you know, drinking beer and carrying on at all hours of the night every night or just about every night. Then I went to college and this was a really shitty little college, it was nothing, but still, I don’t really know where it came from. I can remember sitting there at the table in the library with the advisor and he said, “What’s your major?” And I said, “Hmm. I don’t know. What’s my major? Geology,” I said. I did, I swear, I said geology. So that’s what he put down and that’s what I was listed as. Then about, I guess it was one month into my freshman year, everything went crazy in my head, and I just don’t know where it came from. I’m not maybe thinking clearly right now, but I really don’t know. It really wasn’t a teacher or any fellow students. I just suddenly said, “I want to be a poet and I want to be a poet for a life.” Of course, I had no idea what that meant. I mean, I thought it meant, literally, quite literally, I can remember thinking this, I thought it meant sitting up all night outside around the campfire and reciting your poems to other bums. That’s what I thought my life was going to be. I mean, I didn’t know anything about living poets or anything like that. I just was wildly in love with poetry and I don’t even remember what the first poem could have been. Whitman? I know, thanks to a good freshman teacher who gave me a paperback copy of the Selected Poems of Wallace Stevens, I know that was hugely important. But one thing led to another, I was instantly reading William Carlos Williams and Emily Dickinson. And I read a lot of foreign poets. Yes, yes. I mean, you know, the obvious things like Rilke and Rimbaud and Baudelaire and stuff like that. But I don’t think I really read living poets until I got to Iowa as a graduate student and then I went insane. I mean, I devoured everything the bookstore could offer in a couple months. I was just insane. During my undergraduate period I was very isolated. And then when I became a graduate student, the world just blew open like crazy. It went from I was going to be a vagabond to, ah, I’d like to publish something. I won the Yale award about five months later.

Close

×

Angela Ball

James Tate was a true eccentric — that is, someone outside the realm of the usual, by virtue not of affectation but imagination. J.D. McClatchy has said that his work demonstrates “the surrealism of everyday life” — I can’t agree more. His poetry is weird in its connection with fate and splendid in its connection to the ideal.

I first saw James Tate in 1972, when I was an undergraduate at Ohio University. Three young poets read together that night: Jon Anderson, William Matthews, and James Tate. I remember them being on stage all together. Tate read the very affecting “The Lost Pilot” and the hilarious “The Distant Orgasm.” I believe he also read “The Buddhists Have the Field.”

I was lucky enough to be in London one summer in the nineties when John Ashbery and James Tate read together at the South Bank Arts Centre. Afterwards, I complimented Tate on his reading style. “I didn’t know I had a style,” he said.

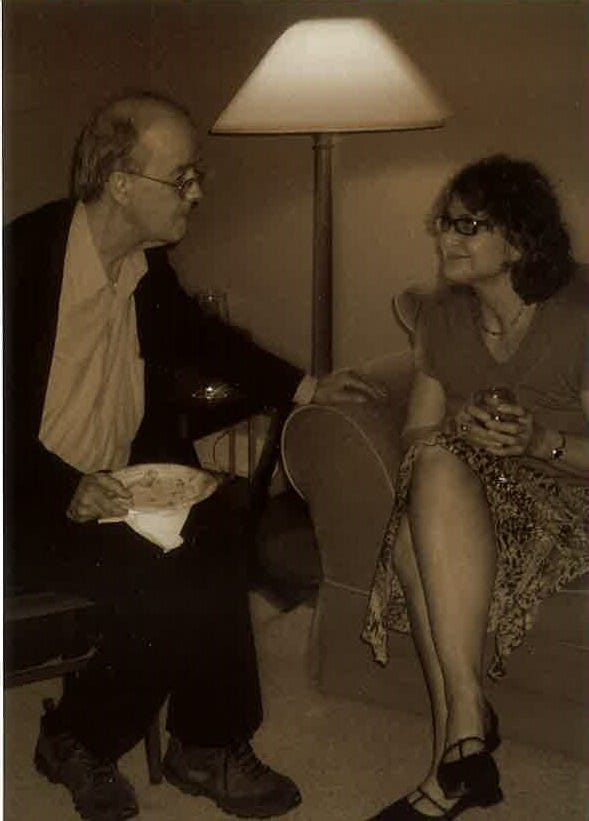

James Tate and Dara Wier visited the Center for Writers in 2006, only a few months after Katrina. Wier is a native of Louisiana. We ate together at Arnaud’s and had a lovely time, though the city was still stunned from the horrors of the manmade flood. In Hattiesburg we ate at Leatha’s, a wonderful barbeque joint housed in a doublewide trailer. The mayor of the city was also having lunch there. This could have happened in a James Tate poem. The reading given by James and Dara was extraordinary, with Dara’s and James’s work conversing back and forth, trading the ineluctable and the ordinary, the down-home and the far-fetched. The reception was at my house, and a picture was taken of James and me in earnest conversation. I imagine us talking of poetry, dogs, and pie.

Close

×

Tyler Mills

Though I never met him, James Tate influenced me a great deal during my MFA. In my last year of the program, I submitted a poem to a contest he was judging (the Third Coast Poetry Prize). I was totally shocked that it won, and I was on cloud nine when I realized that he was actually going to write something about it. He wrote, “The bats, in the end, are what one expects least, and yet they seem to bring the whole poem together” — which, to me, seemed like something I would dream James Tate would write about a poem that was doing what I wanted it to. Hearing this from him confirmed that wild leaps and play with image could work, that one doesn’t always have to close a poem with some kind of return. I wrote him a fan letter to thank him and spent the summer reading and re-reading The Ghost Soldiers. I’m very sad about his passing. The world of poetry still needs him.

Close

×

Contributors

Angela Ball is a professor at the University of Southern Mississippi’s Center for Writers. Her most recent collection is Night Clerk at the Hotel of Both Worlds.

Sarah Blake is the author of Mr. West, an unauthorized lyric biography of superstar Kanye West, out now from Wesleyan University Press.

Eduardo C. Corral is the author of Slow Lightning, winner of the Yale Younger Poets Prize.

Adam Fitzgerald is the author of The Late Parade (Liveright, 2013).

Brian Henry’s tenth book of poetry, Static & Snow, is forthcoming from Black Ocean.

Winner of the Yale Series of Younger Poets competition, Fady Joudah is a Palestinian American physician, poet, and translator. His most recent books are Alight and Textu, both published by Copper Canyon in 2013.

Dorothea Lasky is the author of four books of poetry and teaches at Columbia University’s School of the Arts.

Gail Mazur’s 6th collection of poetry is Figures in a Landscape. She is Senior Distinguished Writer in Residence at Emerson College and Founding Director of the Blacksmith House Poetry Series.

Three-time Pushcart prize winner Jill McDonough directs UMass-Boston’s MFA program and 24PearlStreet, the Fine Arts Work Center online. Her books include Habeas Corpus and Where You Live; Alice James will publish Reaper in 2017.

Tyler Mills is the author of the poetry collection Tongue Lyre. She is an assistant professor at New Mexico Highlands University.

Amy Newman is the author of five books, most recently Dear Editor (2011) and On This Day in Poetry History (forthcoming in 2015).

Joe Pan’s newest collection of poetry, Hiccups, is forthcoming from Augury Books in October 2015.

Matthew Zapruder lives in Oakland, CA., where he is Editor at Large at Wave Books, and teaches in the MFA at Saint Mary’s College. With special thanks to Rebecca Morgan Frank and Lana Lingbo Li. We are indebted to James Tate’s publishers: Ecco Press; Wesleyan University Press; Little, Brown & Co.; Halty Ferguson; and Yale University Press.

Close