Interviews

A Jane Austen Novel for the Internet Age

In “Moderation,” Elaine Castillo follows a content moderator navigating love and intimacy in the darkest corners of the internet

Elaine Castillo’s fiction brings the Filipino diaspora into sharp focus. She populates her novels with the working Filipino (perpetually) underclass, whose precarious labor under capitalism reveals more than a century of intertwined histories between the United States and the Philippines.

In Moderation, Castillo’s sophomore novel, the main character, Girlie Delmundo, descends from a long line of immigrant nurses and caretakers—“her mother was a nurse, her aunts and distant cousins all nurses and maids and cleaners scattered everywhere”—which might explain her aptitude for her job as a content moderator at a social media conglomerate. Content moderation is still care work after all. Girlie moves through the internet like a triage nurse, excising scenes of sexual assault, pedophilia, and other extreme material, absorbing the psychic damage that no algorithm can process. Her moderation team is mostly other Filipinas, after “none of the white people survived” the role’s emotional toll for more than a year. Such are the familiar trajectories of Filipino women who have long stood at the center of the global care economy, crossing oceans to nurse and to clean, to tend and to soothe. By always locating her characters within history—tracing Girlie and her family back through Spanish and American colonization—Castillo opens up new ways of understanding how empire and globalization have shaped contemporary stories of exploitation and lost potential.

Yet Moderation is not a novel about despair—Castillo refuses to linger there; after all, melancholy is boring. Instead, through Girlie’s sharp perspective, she writes with verve and mordant wit, exploring what shapes a life in all its complexity. Castillo is attuned to the small, collective details of Girlie’s world: The quiet romance that blooms in an unlikely place and the choices she must make to survive work, reckon with her history, and allow herself to love.

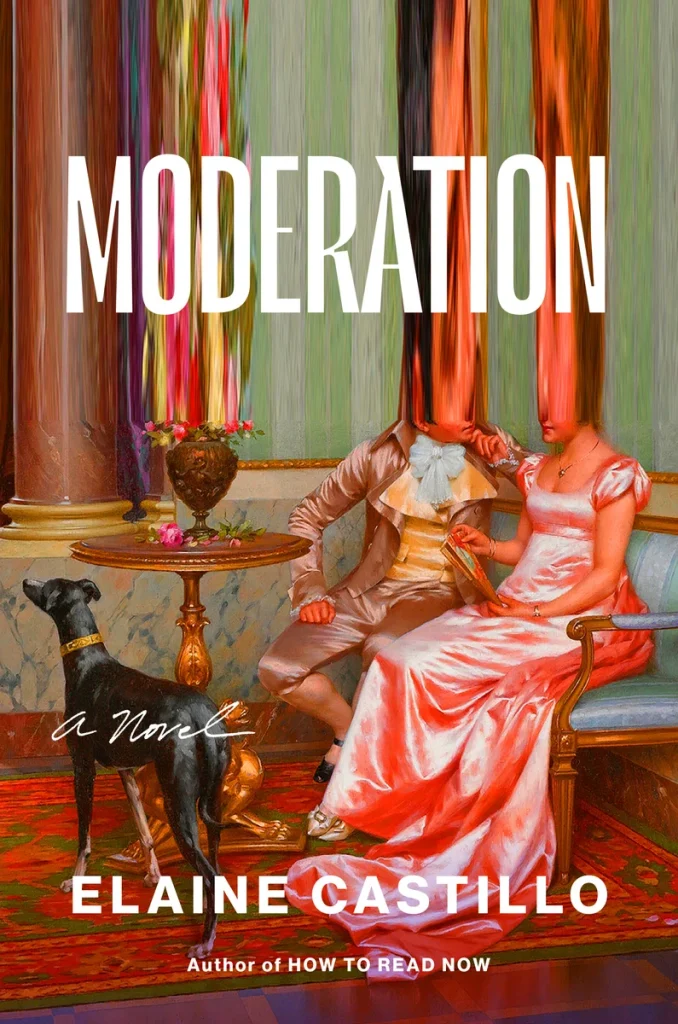

Castillo and I spoke over Zoom about writing happy endings, Melville, eldest-sibling fiction, and her wonderful book cover, which recently made it to the finals of Electric Literature’s Best Book Covers of 2025 contest.

Evander Reyes: Let’s start with the cover. Could you talk about how it came about and what ideas or tensions you hoped it would evoke?

Elaine Castillo: I knew early on what I wanted. I submitted a painting to my editor and the design team and said, “I want this, but glitchy.” Lynn Buckley, the cover designer, came back with this exact version plus five others that were equally amazing. It was the shortest meeting in Viking Press history—we all agreed immediately that she’d nailed it.

The painting is Admiration by Vittorio Reggianini, who belonged to a school called the “Satins and Silks painters.” He depicted Regency-era romance, so if you search images from Pride and Prejudice or Regency romance, his work often comes up. But while he painted that era, he wasn’t alive for it—he was looking back and romanticizing it.

Reggianini died in 1938, meaning he lived through Italy’s rise to fascism. So, here’s this extremely romanticized historical vision being painted during a period of political upheaval, war, and the rise of fascism. That tension—between a nostalgic image of history and the dark realities of the present—connects directly to the book’s themes of how history and romance are reimagined, especially in relation to the tech industry’s collusion with authoritarianism.

ER: In paintings, there’s often some secret history lurking beneath the surface, and the same is true of your fiction. I find it fitting that you interrupt the image of the painting with a glitch. A glitch, after all, disrupts the illusion of normal functioning—it forces us to look at what’s usually concealed, what remains invisible. In many ways, this book operates through a kind of glitch politics, constantly drawing attention to the hidden structures that sustain our world. Why did you choose to center the novel on the invisible content moderators whose labor undergirds our social media lives?

EC: When I started writing this novel, even though I knew I was writing about content moderation, I always thought of it as a novel primarily about labor.

In my research, one of the early articles I read was Adrian Chen’s 2014 Wired piece, “The Laborers Who Keep Dick Pics and Beheadings Out of Your Facebook Feed.” At that time, it identified so many content moderators as Filipino. When I realized how much of this labor was done within the Filipino community—and even possibly within my family—I started linking it to other forms of racialized labor in my diaspora, like nursing. My mom was a nurse. My dad worked as a security guard for computer chip companies. It was easy to see the connections: Who does the cleanup work for an industry, who carries the burdens of that labor, both materially and psychically?

I always thought of it as a novel primarily about labor.

That’s where my thinking on content moderation came from. I also knew I had no desire to write a novel centering a tech oligarch or someone part of the C-suite. I didn’t want to critique the tech industry from the top down. What interested me was illuminating the lives of tech’s most anonymous laborers. And when I was researching, most of the articles I found were understandably harrowing, with a tragic bent, because this labor is so punishing. But the job of fiction is to imagine people as more than just the worst thing that ever happened to them.

ER: Some readers might be surprised by the fact that in this industry, in such a brutal role, Filipinos are so present. But your book tells this history so well: how the Philippines and Filipinos often find themselves both at the center and at the margins of these accelerated processes of late-stage capitalism.

EC: Absolutely. I mean, Cambridge Analytica rehearsed how to dismantle democracy in the Philippines before applying those tactics to elections in the UK and the US. Concerning content moderation, exploitation under capitalism is constantly evolving, but the links remain clear: Working-class labor that upholds entire industries is still connected to colonial and imperial structures, and it’s still the same groups who are exploited to maintain the center. That narrative hasn’t changed.

ER: The book’s engagement with tech dystopia and the effects of global capitalism kept bringing me back to the opening epigraph—the Melville quote from Moby Dick about New Bedford as a queer, or uncanny place. In that section, Melville writes about a beautiful, prosperous city whose wealthy veneer is built on the violence and exploitation of the whaling industry. Why start with this Melville quote?

EC: Fewer people ask about this epigraph! Everyone always asks about the second epigraph, the Terminator 2 quote. I love the playful contrast of Terminator with Moby Dick because it signals the sensibilities the book is playing with. I had just finished Moby Dick when I returned to this novel after pausing it in 2018 to write a book of essays, How to Read Now. Moby Dick is sort of America’s first workplace novel, or at least an early great workplace novel. That quote stuck out to me because it’s such a succinct and perceptive description of the labor that undergirds American society. Melville imagines all these patrician houses as being dragged up from the bottom of the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, made possible entirely by the backbreaking labor of whaling.

And in a way, it’s similar to the end of another novel, one of my favorites: Émile Zola’s Germinal. It’s a French novel that follows a mining community and their struggle to organize a strike in the post-industrial revolution era. At the end of the book—spoiler alert for something written in the 1800s—the revolution ultimately fails, and the main character walks off, but as he walks across the field, he imagines all the well-made French towns above being supported by the miners underground. Their work literally sustains the towns, but Zola frames it as seeds waiting to sprout, a potential revolution in the making. That’s where germinal comes from—seeds germinating. That connection, how both Melville and Zola imagines the way labor sustains society, is what I’m drawing from in my novel.

ER: I found Moderation to be an enormously hopeful book—even amid a world dominated by tech, oligarchs, and capitalism. Even as Girlie’s life is shaped by these crises, there’s still a sense of possibility. Did you set out to write a hopeful novel?

EC: There were different possible endings for the book. At one point, it was even a direct sequel to my first novel, America Is Not the Heart, because I thought I had to be explicit about the destruction of that community. There was also a version that was much more politically explicit, one that would’ve satisfied my critical or political impulses. But I realized I was also using these different endings as a way to avoid doing the vulnerable work the book was really asking of me. And deep down, I always knew I wasn’t going to write an unhappy ending. Spoiler alert.

Something that bothers me about how stories of resistance or revolution are usually depicted is that they’re almost always grim. They suggest you have to sacrifice love and connection for the cause, or they end in tragedy. And then, in contrast, happy endings or romance get dismissed as pat.

I remember giving a craft talk where I was making the case for the politics of the happy ending, and I could see students getting uncomfortable. They’d been taught that happy endings are simplistic. But I told them: If you write about someone who lives a tragic life that ends tragically, it can also be pat depending on how it’s written. There’s no inherent moral value that makes a tragic ending more serious or hope and optimism less so. Still, it’s funny how we absorb this idea of what counts as serious and what doesn’t.

ER: Your work is in some ways writing against a certain kind of woman, usually white, that’s become very familiar terrain in fiction and television in the last decade or so. She is this unmoored depressive figure who is self-sabotaging and reckless. This character might be found in Girlie’s younger sister Maribel, but Girlie is none of those things. Can you talk about the extreme competence of Girlie?

EC: I like to joke that this book is for eldest siblings. It’s an eldest daughter book. I’m tired of messy fiction—it’s younger sibling propaganda! We need more repressed, highly competent, parentified eldest sibling fiction. This book is my contribution to that genre.

There’s no inherent moral value that makes a tragic ending more serious or hope and optimism less so.

That said, I do love a lot of that messy fiction and art. I only just watched Fleabag—because I’m late to everything. Phoebe Waller-Bridge’s character is the kind of messy character that is representative of this genre, but as I was watching I kept thinking we need more of the older sister Claire’s story. The sister who’s just martialing her way through life. To me, Claire feels very Girlie-coded. I don’t see this type of woman in fiction as much. I certainly see her in my life—or in the mirror. But sometimes I just think: Life is messy enough.

The narrative for Girlie, of course, is that she might be messier inside than she admits. But I think the other big source of drama for Girlie and her love interest, William, is that they’re people who self-identify as fixers. They’re like, I’m the one who handles everything, I’m the one who keeps it all together. And that can be a really convenient way to avoid looking at your own life. At some point it’s like, look at yourself, bitch.

ER: Girlie and William both sound like Virgos.

EC: Oh my god, I was just about to say that. This book is definitely about Virgo problems. Girlie is absolutely a Virgo—same as me. They both have a lot of Earth. They might both be Capricorn Moons. I think William’s sun sign is Aquarius though, and I have a lot of Aquarians in my life, so that tracks.

ER: We have to talk about virtual reality. In this novel, VR plays two strikingly different roles. On one hand, it offers simulations of ancient civilizations that gamers explore for entertainment. On the other, it serves a therapeutic purpose where immersive VR experiences actually reprogram the nervous system, reshaping the body’s relationship to reality in ways that can lead to healing. In what ways did you want these very different approaches to VR to interact within the story?

EC: When I started writing the early kernels that eventually became this novel, it wasn’t necessarily about content moderation. It was more of a sci-fi novel in my mind, thinking about speculative forms of therapy, formative harm, and related ideas. When I started reading about content moderation, I wanted to take that labor and imagine it in a more speculative context. I also knew I was writing about virtual reality.

The VR in the book is not the VR we have now. But for the therapeutic side, I wanted to respect the clinical science. In my research, I found real work on virtual-reality therapy. It’s a legitimate science, and the book by Brennan Spiegel, Vrx: How Virtual Therapeutics Will Revolutionize Medicine, is cited in my book’s acknowledgements and was really influential. His work explores how VR is used in clinics to treat things like depression or chronic pain. Many of the VR therapy sessions I wrote about are closely modeled to what Spiegel describes or what I read in other articles. I wanted that science to feel grounded, even though the VR in the book is far ahead of current technology.

I’m tired of messy fiction—it’s younger sibling propaganda!

One reason I wanted to write about this is connected to what we were discussing earlier. I was interested in exploring the dystopian aspects of tech without writing a straightforward tech dystopia. I don’t want to immediately surrender to technophobia. Yes, the tech industry repeats exploitative cycles that have existed for hundreds of years. It’s extractive, colonial, environmentally destructive, and harms people around the world. But if that were the only truth, it would be easier to divest from it. I was interested in the push and pull: how technologies can seduce us, connect us, and what draws us to them. I wanted to explore how someone can be seduced by a technology while simultaneously being exploited by it. Part of the thematic focus of the book is exploring how complex our relationships with technology are, how it acts on us viscerally, and how those forces intersect with labor, exploitation, and the possibilities of repair.

ER: Your first book, America’s Not the Heart, clearly nods to the classic Filipino text America Is in the Heart by Carlos Bulosan. How do you think about the literary inheritance of the Filipino novel, and which works do you see Moderation being in conversation with?

EC: Honestly, sometimes I can only see these connections after having written the book. You have this vague sense of influence while you’re working. Though I knew I’d been shaped by William Gibson. My dad bought me Idoru when I was around 13, and I didn’t reread it while writing because I thought, “It’s already in my brain; I don’t need to revisit it.” But after Moderation was published, I looked back and realized, yes, it’s literally about a rock star who wants to marry a VR idol. Anyone writing about virtual reality is inheriting everything Gibson wrote about.

At the same time, because of the romance aspect and the way love is repressed in the novel, I realized I was riffing on Jane Austen too. I had written a bit about Austen in How to Read Now, especially how people add political and social context to her novels. While writing, I started thinking, “If I were to write an Austen-esque novel today, what would that look like?” I didn’t plan it explicitly, but that’s definitely what was happening. So, in a way, it’s like Gibson and Austen are in conversation. It’s genre-jumping, yes, but Gibson’s novels always have romance in them, so these genres coexist naturally. I knew I was writing both a sci-fi novel and a love story, so those were the lineages I was consciously drawing from.