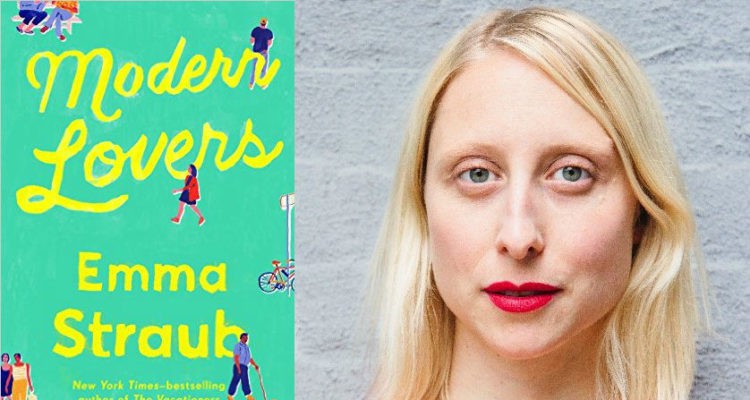

Lit Mags

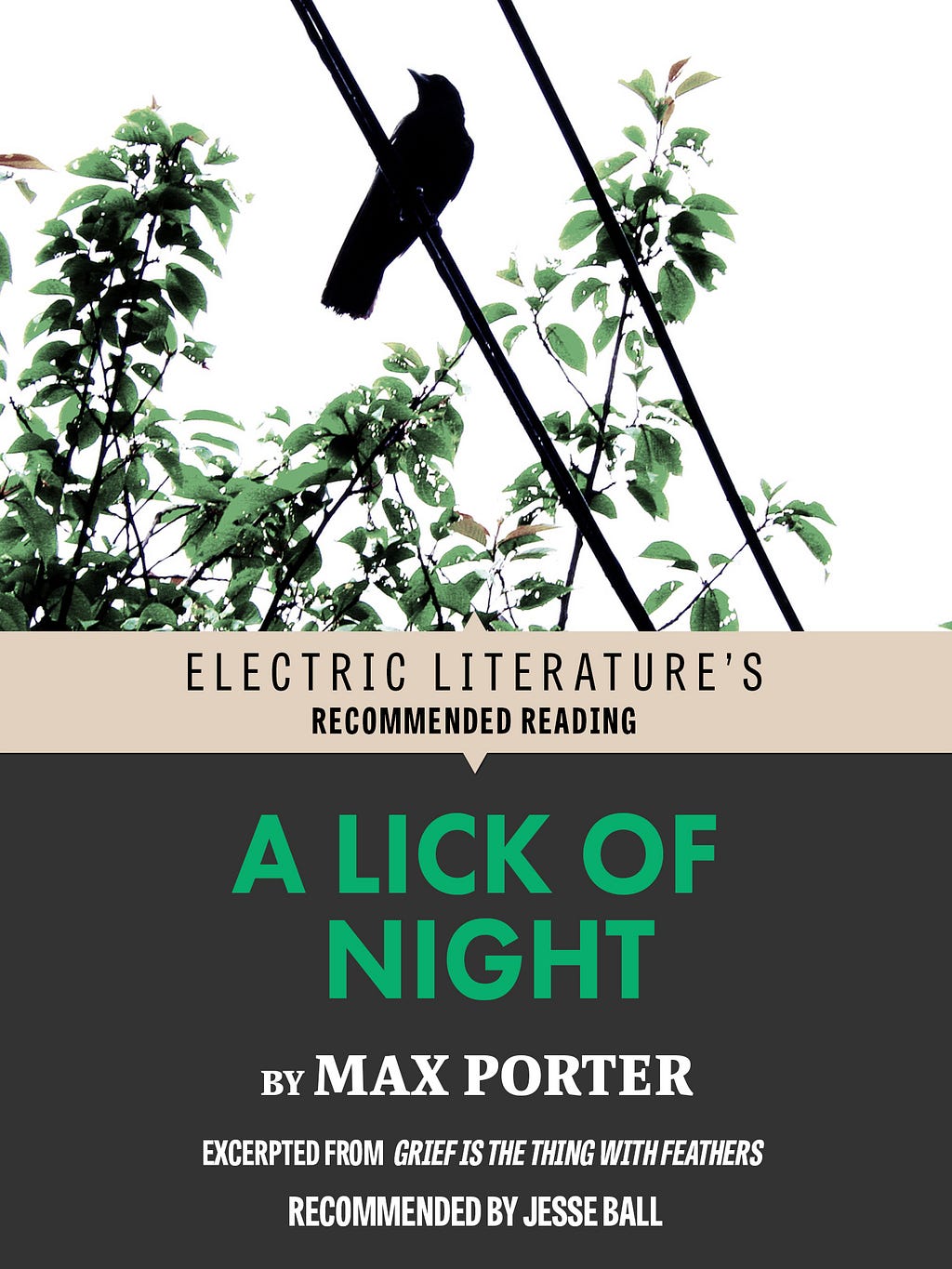

“A Lick of Night” by Max Porter

A story about the bizarreness of grief

AN INTRODUCTION BY JESSE BALL

Let’s imagine that there’s a device and it’s made of paper. What more can we say about it? It is a sort of machine, and it contains within it many more machines. The inventor of the machine is a man named Max Porter. He lives in London. He has a family. He looks a bit disreputable in a train car or on a bus. He does many things, and one of those things, so it would seem, involved creating of a special sort of paper machine for conveying grief.

I met him, and I must say, he does not look like a person who makes paper grief machines. But the marvels of Max Porter’s mind are visible as soon as he opens his mouth. His life has created in him a person capable of extraordinary feeling. I imagine it must have been painful.

However that may be, here’s what happens when you find this paper machine, you pick it up, you turn it, lift it, fold it, set it down. You assemble in it and through it thoughts you hadn’t had before, vivid and strong Max Porter thoughts that a person should have before they die.

I think it would be a mistake for you to finish whatever other book you might be reading currently. Perhaps it’s good — but is it necessary? Will it change you? I want you to do the important things from now on, and leave out the useless things.

Please, this minute, read Grief is the Thing with Feathers.

Jesse Ball

Author of A Cure for Suicide

“A Lick of Night” by Max Porter

Max Porter

Share article

BOYS

There’s a feather on my pillow.

Pillows are made of feathers, go to sleep. It’s a big, black feather.

Come and sleep in my bed.

There’s a feather on your pillow too.

Let’s leave the feathers where they are and

sleep on the floor.

DAD

Four or five days after she died, I sat alone in the

living room wondering what to do. Shuffling around,

waiting for shock to give way, waiting for any kind of

structured feeling to emerge from the organizational

fakery of my days. I felt hung-empty. The children

were asleep. I drank. I smoked roll-ups out of the

window. I felt that perhaps the main result of her

being gone would be that I would permanently

become this organizer, this list-making trader in

clichés of gratitude, machine-like architect of routines

for small children with no Mum. Grief felt fourth-

dimensional, abstract, faintly familiar. I was cold.

The friends and family who had been hanging around

being kind had gone home to their own lives. When

the children went to bed the flat had no meaning,

nothing moved.

The doorbell rang and I braced myself for more

kindness. Another lasagne, some books, a cuddle,

some little potted ready-meals for the boys. Of

course, I was becoming expert in the behavior of

orbiting grievers. Being at the epicenter grants

a curiously anthropological awareness of everybody

else; the overwhelmeds, the affectedly lackadaisicals,

the nothing so fars, the overstayers, the new best

friends of hers, of mine, of the boys. The people I still

have no fucking idea who they were. I felt like Earth

in that extraordinary picture of the planet surrounded

by a thick belt of space junk. I felt it would be years

before the knotted-string dream of other people’s

performances of woe for my dead wife would thin

enough for me to see any black space again, and

of course–needless to say–thoughts of this kind

made me feel guilty. But, I thought, in support of

myself, everything has changed, and she is gone and

I can think what I like. She would approve, because

we were always over-analytical, cynical, probably

disloyal, puzzled. Dinner party post-mortem bitches

with kind intentions. Hypocrites. Friends.

The bell rang again.

I climbed down the carpeted stairs into the chilly

hallway and opened the front door.

There were no streetlights, bins or paving stones. No

shape or light, no form at all, just a stench.

There was a crack and a whoosh and I was smacked

back, winded, onto the doorstep. The hallway was

pitch black and freezing cold and I thought, ‘What

kind of world is it that I would be robbed in my home

tonight?’ And then I thought, ‘Frankly, what does it

matter?’ I thought, ‘Please don’t wake the boys, they

need their sleep. I will give you every penny I own

just as long as you don’t wake the boys.’

I opened my eyes and it was still dark and everything

was crackling, rustling.

Feathers.

There was a rich smell of decay, a sweet furry stink of

just-beyond-edible food, and moss, and leather, and

yeast.

Feathers between my fingers, in my eyes, in my

mouth, beneath me a feathery hammock lifting me up

a foot above the tiled floor.

One shiny jet-black eye as big as my face, blinking

slowly, in a leathery wrinkled socket, bulging out

from a football-sized testicle.

SHHHHHHHHHHHHH.

shhhhhhhh.

And this is what he said:

I won’t leave until you don’t need me any more.

Put me down, I said.

Not until you say hello.

Put. Me. Down, I croaked, and my piss warmed the

cradle of his wing.

You’re frightened. Just say hello.

Hello.

Say it properly.

I lay back, resigned, and wished my wife wasn’t

dead. I wished I wasn’t lying terrified in a giant

bird embrace in my hallway. I wished I hadn’t been

obsessing about this thing just when the greatest

tragedy of my life occurred. These were factual

yearnings. It was bitterly wonderful. I had some

clarity.

Hello Crow, I said. Good to finally meet you.

And he was gone.

For the first time in days I slept. I dreamt of

afternoons in the forest.

CROW

Very romantic, how we first met. Badly behaved. Trip

trap. Two-bed upstairs at, spit-level, slight barbed-

error, snuck in easy through the wall and up the attic

bedroom to see those cotton boys silently sleeping,

intoxicating hum of innocent children, lint, flack,

gack-pack-nack, the whole place was heavy mourning,

every surface dead Mum, every crayon, tractor, coat,

welly, covered in a lm of grief. Down the dead Mum

stairs, plinkety plink curled claws whisper, down to

Daddy’s recently Mum-and-Dad’s bedroom. I was

Herne the hunter hornless, funt. Munt. Here he is.

Out. Drunk-for white. I bent down over him and

smelt his breath. Notes of rotten hedge, bluebottles.

I prised open his mouth and counted bones, snacked

a little on his un-brushed teeth, flossed him, crowly

tossed his tongue hither, thither, I lifted the duvet.

I Eskimo kissed him. I butterfly kissed him. I flat-

flutter Jenny Wren kissed him. His lint (toe-jam-rint)

fuck-sacks sad and cosy, sagging, gently rising, then

down, rising, then down, rising, then down, I was

praying the breathing and the epidermis whispered

‘flesh, aah, flesh, aah, flesh, aah,’ and it was beautiful

for me, rising (just like me) then down (just like me)

pan-shaped (just like me) it was any wonder the facts

of my arrival under his sheets didn’t lift him, stench,

rot-yot-kot, wake up human (BIRD FEATHERS

UP YER CRACK, DOWN YER COCK-EYE, IN

YER MOUTH) but he slept and the bedroom was

a mausoleum. He was an accidental remnant and I

knew this was the best gig, a real bit of fun. I put my

claw on his eyeball and weighed up gouging it out for

fun or mercy. I plucked one jet feather from my hood

and left it on his forehead, for, his, head.

For a souvenir, for a warning, for a lick of

night in the morning.

For a little break in the mourning.

I will give you something to think about, I whispered.

He woke up and didn’t see me against the blackness

of his trauma.

ghoeeeze, he clacked.

ghoeeeze.

DAD

Today I got back to work.

I managed half an hour then doodled.

I drew a picture of the funeral. Everybody had crow

faces, except for the boys.

CROW

Look at that, look, did I or did I not, oi, look, stab it.

Good book, funny bodies, open door, slam door, spit

this, lick that, lift, oi, look, stop it.

Tender opportunity. Never mind, every evening,

crack of dawn, all change, all meat this, all meat that,

separate the reek. Did I or did I not, ooh, tarmac

macadam. Edible, sticky, bad camouflage.

Strap me to the mast or I’ll bang her until my

mathematics poke out her sorry, sorry, sorry, look! A

severed hand, bramble, box of swans, box of stories,

piss-arc, better off, must stop shaking, must stay still,

mast stay still.

Oi, look, trust me. Did I or did I not faithfully

deliver St Vincent to Lisbon. Safe trip, a bit of liver,

sniff, sniff, fabric softener, leather, railings melted

for bombs, bullets. Did I or did I not carry the hag

across the river. Shit not, did not. Sing song blackbird

automatic fuck-you-yellow, nasty, pretty boy, joke,

creak, joke, crech, joke. Patience.

I could’ve bent him backwards over a chair and drip-

fed him sour bulletins of the true one-hour dying of

his wife. OTHER BIRDS WOULD HAVE, there’s

no goody baddy in the kingdom. Better get cracking.

I believe in the therapeutic method.

BOYS

We were small boys with remote-control

cars and ink-stamp sets and we knew

something was up. We knew we weren’t

getting straight answers when we asked

‘where is Mum?’ and we knew, even

before we were taken to our room and

told to sit on the bed, either side of Dad,

that something was changed. We guessed

and understood that this was a new life

and Dad was a different type of Dad now

and we were different boys, we were brave

new boys without a Mum. So when he

told us what had happened I don’t know

what my brother was thinking but I was

thinking this:

Where are the fire engines? Where is the

noise and clamor of an event like this?

Where are the strangers going out of their

way to help, screaming, flinging bits of

emergency glow-in-the-dark equipment

at us to try and settle us and save us?

There should be men in helmets speaking

a new and dramatic language of crisis.

There should be horrible levels of noise,

completely foreign and inappropriate for

our cozy London flat.

There were no crowds and no uniformed

strangers and there was no new language

of crisis. We stayed in our PJs and people

visited and gave us stuff.

Holiday and school became the same.

CROW

In other versions I am a doctor or a ghost. Perfect

devices: doctors, ghosts and crows. We can do things

other characters can’t, like eat sorrow, un-birth secrets

and have theatrical battles with language and God. I

was friend, excuse, deus ex machina, joke, symptom,

figment, specter, crutch, toy, phantom, gag, analyst

and babysitter.

I was, after all, ‘the central bird … at every extreme.’

I’m a template. I know that, he knows that. A myth

to be slipped in. Slip up into.

Inevitably I have to defend my position, because my

position is sentimental. You don’t know your origin

tales, your biological truth (accident), your deaths

(mosquito bites, mostly), your lives (denial, cheerfully).

I am reluctant to discuss absurdity with any of you,

who have persecuted us since time began. What good is

a crow to a pack of grieving humans? A huddle.

A throb.

A sore.

A plug.

A gape.

A load.

A gap.

So, yes. I do eat baby rabbits, plunder nests, swallow

filth, cheat death, mock the starving homeless,

misdirect, misinform. Oi, stab it! A bloody load of

time wasted.

But I care, deeply. I find humans dull except in grief.

There are very few in health, disaster, famine, atrocity,

splendor or normality that interest me (interest

ME!) but the motherless children do. Motherless

children are pure crow. For a sentimental bird it is

ripe, rich and delicious to raid such a nest.

DAD

I’ve drawn her unpicked, ribs splayed stretched like a

xylophone with the dead birds playing tunes on her

bones.

CROW

I’ve written hundreds of memoirs. It’s necessary for

big names like me. I believe it is called the imperative.

Once upon a time there was a blood wedding, and the

crow son was angry that his mother was marrying

again. So he flew away. He flew to find his father

but all he found was carrion. He made friends with

farmers (he delivered other birds to their guns),

scientists (he performed tricks with tools that not

even chimps could perform), and a poet or two. He

thought, on several occasions, that he had found

his Daddy’s bones, and he wept and screamed at the

hateful Goshawks ‘here are the grey bones of my

hooded Papa,’ but every time when he looked again

it was some other corvid’s corpse. So, tired of the

fable lifestyle, sick of his omen celebrity, he hopped

and flew and dragged himself home. The wedding

party was still in full swing and the ancient grey crow

rutting with his mother in the pile of trash at the foot

of the stairs was none other than his father. The crow

son screamed his hurt and confusion at his writhing

parents. His father laughed. KONK. KONK. KONK.

You’ve lived a long time and been a crow through and

through, but you still can’t take a joke.

DAD

Soft.

Slight.

Like light, like a child’s foot talcum-

dusted and kissed, like stroke-reversing suede, like

dust, like pins and needles, like a promise, like a curse,

like seeds, like everything grained, plaited, linked, or

numbered, like everything nature-made and violent

and quiet.

It is all completely missing. Nothing patient now.

BOYS

My brother and I discovered a guppy fish in a

rock pool somewhere. We set about trying to

kill it. First we flung shingle into the pool but

the fish was fast. Then we tried large rocks and

boulders, but the fish would hide in the corners

beneath small crevices, or dart away. We were

human boys and the fish was just a fish, so

we devised a way to kill it. We filled the pool

with stones, blocking and damming the guppy

into a smaller and smaller area. Soon it circled

slowly and sadly in the tiny prison-pool and

we selected a perfectly sized stone. My brother

slammed it down over-arm and it popped and

splashed, rock on rock in water and delightedly

we lifted it out. Sure enough the fish was dead.

All the fun was sucked across the wide empty

beach. I felt sick and my brother swore. He

suggested flinging the lifeless guppy into the

sea but I couldn’t bring myself to touch it so

we sprinted back across the beach and Dad

didn’t look up from his book but said

‘you’ve done something bad I can tell.’

DAD

We will never fight again, our lovely, quick, template-

ready arguments. Our delicate cross-stitch of bickers.

The house becomes a physical encyclopedia of no-

longer hers, which shocks and shocks and is the

principal difference between our house and a house

where illness has worked away. Ill people, in their

last day on Earth, do not leave notes stuck to bottles

of red wine saying ‘OH NO YOU DON’T COCK-

CHEEK.’ She was not busy dying, and there is no

detritus of care, she was simply busy living, and then

she was gone.

She won’t ever use (make-up, turmeric, hairbrush,

thesaurus).

She will never finish (Patricia Highsmith novel,

peanut butter, lip balm).

And I will never shop for green Virago Classics for

her birthday.

I will stop finding her hairs.

I will stop hearing her breathing.

BOYS

We found a fish in a pool and tried to kill

it but the pool was too big and the fish was

too quick so we dammed it and smashed it.

Later on, for ages, my brother did pictures

of the pool, of the fish, of us. Diagrams

explaining our choices. My brother always

uses diagrams to explain our choices, but

they aren’t scientific, they’re scrappy. My

brother likes to do scrappy badly drawn

diagrams even though he can actually

draw pretty well.

CROW

Head down, tot-along, looking.

Head down, hop-down, totter.

Look up. ‘LOUD, HARD AND INDIGNANT

KRAAH NOTES’ (Collins Guide to Birds, p. 45).

Head down, bottle-top, potter.

Head down, mop-a-lot, hopper.

He could learn a lot from me.

That’s why I’m here.

DAD

There is a fascinating constant exchange between

Crow’s natural self and his civilized self, between

the scavenger and the philosopher, the goddess of

complete being and the black stain, between Crow

and his birdness. It seems to me to be the self-same

exchange between mourning and living, then and

now. I could learn a lot from him.