interviews

A Life Described in Teeny Tiny Pieces

Poet Beth Ann Fennelly discusses her new collection of ‘micro-memoirs’

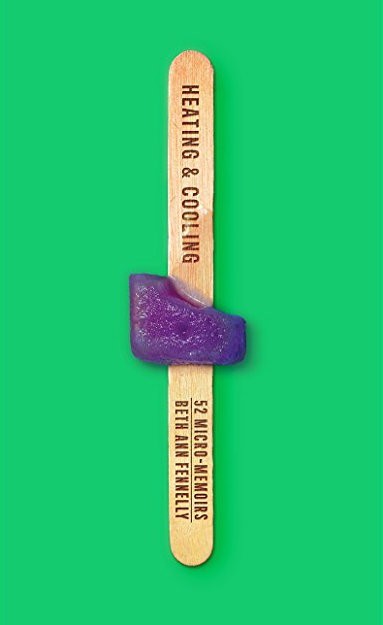

Beth Ann Fennelly began her career as a poet, but over the course of seven books, her work has continued to branch out in terms of experimentation and collaboration. Her most recent book, Heating & Cooling: 52 Micro-Memoirs, uses short-form prose—some as short as a sentence—to explore the fleeting moments that become persistent memories.

With a consistently beautiful economy of language, Fennelly tells small stories that ask the reader to focus on tiny moments, and how those moments build into the arc of a life. From entertaining factoids about the poet’s past (did you know Fennelly played the Mary Poppins to Vince Vaughn’s Mr. Banks in an elementary school production?) to deep truths about friendship, marriage, parenting, and aging, Heating & Cooling expresses a life in a distinct and unusual form for memoir. The vignettes are consistently entertaining, but always poised, eloquent, and full of moments of tenderness.

Over email, Beth Ann and I talked about creative anxiety, her exploration of structure, and the portrayal of middle-aged love.

RS: Your book perfects a version of the vignette format. Have you always worked in this style, or did it develop in your work over time?

BF: This form is a departure for me. Before I published this book, my husband and I wrote a collaborative novel. Called The Tilted World (HarperCollins, 2013), it was set in the flood of the Mississippi River in 1927, and it ended up being a big project. Although we’d published four books each, we’d never written one together. In addition to teaching ourselves how to collaborate, we had to do a lot of research. And it was high stakes: we spent four years writing the novel. Imagine, if it failed, how costly that would have been for our marriage.

Luckily, it didn’t fail. After we returned from book tour, tuckered, I wasn’t sure what I wanted to write next. There followed a long, frustrating fallow period in which I wasn’t writing. I was scribbling little thoughts and ideas in my notebook — some just a sentence, or a paragraph, the longest just a few pages — but nothing was adding up to anything. Eventually, however, it occurred to me that I was enjoying this scribbling. After the high stakes, research-heavy, character-imbedded thinking of the novel, my own life seemed rich material again. The little memories or quirky thoughts or miniature scenes I was creating seemed refreshing. So, strangely, I identified the feeling of writing before I identified the activity. I thought, What if this “not writing” I’m doing actually is writing, and I just don’t recognize it because it doesn’t look like other writing I’ve done? What if I need to stop waiting for these things to add up to something, and realize maybe they already are somethings, just small? Once I’d recognized the form and gave it the name the micro-memoirs, I realized I was almost done with a book.

What if this “not writing” I’m doing actually is writing, and I just don’t recognize it because it doesn’t look like other writing I’ve done?

RS: From the first micro-memoir, “Married Love,” which continues with “Married Love II, III, IV, etc.” throughout the book, you begin a theme that I was trying to put a name to—it seemed almost like domestic humor. How did you build these pieces over time, and how did you choose these specific anecdotes from your marriage?

BF: “Domestic humor” — what a great term! In this sequence, I was thinking about middle-aged love. This year my husband and I will celebrate our 20th anniversary, and I still think he’s sorta awesome about 98.3 percent of the time. When we met, I’d write him all of these gushy romantic love poems. And while I still love him, and still write about him, the role he plays in my work is different now — he’s not the singular obsessive focus of my work, and sometimes he’s relegated to the margins. But there’s a bit of comfort in that, too — that if I take my gaze away from him, he’s not disappearing. Also, the kind of love we have has, of course, changed from that first-bloom erotic intensity to something more mellowed and complex and richer and funnier. I wanted to look at that, because our society tends to only portray early love, or unrequited love. Middle-age love hasn’t captured our imaginations, so it was fun to investigate.

RS: The book is very funny; do you make an effort to put humor into your writing or does your general sense of humor find its way onto the page?

BF: I don’t sit down and try to be funny — I just try to capture the events of my days, and any day is full of a lot of funny moments, if you just take time to notice them. Motherhood is funny. Sweet and noble and exasperating and empowering — but also funny. I wanted the book to capture the fullness of the human experience — and humor is a big part of being human.

A Poet Survives Abuse, Brain Trauma, and a Hurricane, Then Turns to Memoir

RS: What’s your process for deciding what form a memory takes in writing?

BF: I think when the memories come, they arrive with a kind of feel. Some want to be dreamy, more poetic, have elongated syntax, or be rich with metaphor. Some want to move very fast and need a short sentences or a flat tone. Some need white space to moderate and provide a moment of reflection that allows a difficult trope to touch down. Each piece seems to have its own requirements and I just try to use my ear to figure it out.

It was important to me that the book have a lot of stylistic variation and look different on the page — I wanted to keep the reading experience lively.

RS: How do you select the stories that made it into this edition? Did you have a unifying theme? Do you have any sections that you cut that were particularly difficult to part with?

BF: An early draft of the book had 100 pieces. My editor suggested I cut it down, not because any of the micro-memoirs were huge pieces of garbage, but because the book felt a little overwhelming. So I cut down pieces that seemed like outliers, thematically. I kept ones that focused on my central roles — wife, mother, writer, woman — and hoped the cuts allowed a kind of coalescing among these central roles. The book is in some ways about the choices we make in an effort to be happy.

I wanted the book to capture the fullness of the human experience — and humor is a big part of being human.

RS: I loved the piece “Nine Months in Madison” — I’m from there! But I loved how the piece elucidated artistic anxiety through a sense of place. How did you reach that intersection of place and anxiety with this piece?

BF: Oh Madison is such a cool city! But while I lived there, I was feeling a lot of pressure to figure out what I would do next for a job, and how I would manage to make a living. I was really poor. And I was training for a marathon, circling Madison’s lakes endlessly, and circling the dilemma of my future endlessly, and I used the form of random pieces of information about my time there — information that linked up but didn’t fully construct a narrative — with information about Madison, like how many people have drowned in the lake, especially Otis Redding. I wanted a kind of itchy feel to come out of these numbered sections that would be both self-portrait and city portrait — or, as you put it, the intersection of place and anxiety.

Support Electric Lit: Become a Member!

RS: In the piece “Daughter, They’ll Use Even Your Own Gaze to Wound You,” I loved the approach you took to discussing various forms of harassment — can you talk about approaching very serious topics like this through art?

BF: That micro-memoir details in three paragraphs the three times in my life when a man exposed his genitals to me. The times took place in different cities, when I was at different ages. I always assumed this was a very unusual thing that I’d been exposed to three times, but one time I was in a conversation with six women and five of them described similar experiences. It made me consider the omnipresence of threat for women — that these experiences are so common — that women just have to accept this as part of what it means to be a woman, and have eyes that someone might, at any time, place something wounding in front of. I wrote the three paragraphs with a two-sentence rhyming couplet at the end, so it’s kind of a fucked up sonnet. Not that a reader would need to know that — just that the Shakespearian sonnet form was in the back of my head as a model. Sometimes it’s the presence of art that can help us shape these experiences, construct an arc that offers meaning to the randomness of life.