Interviews

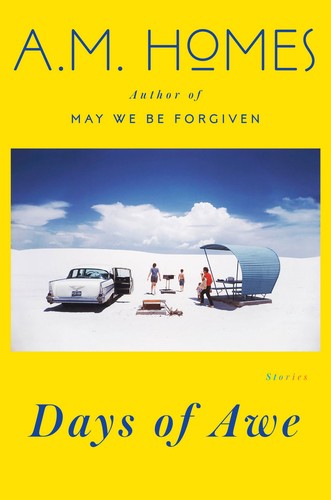

A.M. Homes on What it Means to be A Moral Writer

The author of ‘Days of Awe’ talks about writing stories to illustrate the human heart and why we shouldn’t care if characters are likeable

A.M. Homes’s Days of Awe is a strong short story collection that scales and unpacks, without judgment, the labyrinth of layers that influence human behavior in what Homes celebrates as being “in all its inglorious beauty.” In the path blazed by Grace Paley, her former teacher, Homes writes the truth according to her characters. Brother on Sunday, the collection’s opening story, embodies Homes’s uncluttered intelligence to trust that a story can be kept simple and remain complex, stinging, ambitious and ongoing.

Days of Awe’s precise details straddle comfort and pain with authenticity. Its meticulous pacing borrows from a gymnast’s scissoring and soaring routine on a pommel horse. The non-autobiographical material tunnels into the territory of global consciousness at a critical point in our history. Homes’s devoted readership will take pleasure in a few pieces that are legacy tales from her earlier works, and which provide a continuation and evolution of preexisting characters. And those new to Homes’s work will appreciate her mastery of the dynamics of siblings, life partners, friends, strangers and strangeness all of which are both contrasting and combustible.

The author and I corresponded via email about writing stories to illustrate the human heart, why we shouldn’t care if characters are likeable, and what it means to be moral writer.

Yvonne Conza: The title story Days of Awe circles around a love affair sparked between former friends reunited at a genocide conference. What were you going for in this story in the big and small picture?

A.M. Homes: I am always trying to tell the story as well as I can, and to be true to my characters. Grace Paley always said, write the truth according to the character.

I am interested in how quickly awareness of the Holocaust is fading –how we don’t seem to notice that there are genocides all over the world and how even in these horrible moments, people want a sense of connection, they continue to be human, they mate, they love and when it is all over those who have survived have mixed feelings about what it means to survive and their duty to those who were lost. To me it’s heartbreaking and so very real. And then we make judgments about whose story is most valid, who has the right to tell the tale — and I find that interesting as well. And now, many Holocaust survivors have died from old age — and I am conscious of who is left to tell the story — who is left to remind us. My work is often about taking the collective unconscious and making it collectively conscious.

My work is often about taking the collective unconscious and making it collectively conscious.

YC: The Days of Awe are the ten days from Rosh Hashanah to Yom Kippur when the sins of the previous year are examined and repented for. Each of the stories in the collection resonates with the ideas of reflection and repentance, with a depth that goes beyond the literal . What went into your process of tailoring a more individualized and nuanced interpretation of “Days of Awe” to each story?

A.M.: I’m not exactly sure how to answer it –except to say that the resonance you felt, is what I intended. I am interested in history and how it plays out over many years on the lives of people — somehow we often separate historical events from human lives. There are three stories about war in the collection — two deal with fall out from WW2 (“Days of Awe” and “Whose Story Is It, and Why Is It Always on Her Mind?”). “Whose Story Is It, and Why Is It Always on Her Mind?” is set in Europe/England. And “The National Cage Bird Show” — a modern story about war written in relation to Salinger’s For Esmé, with Love and Squalor.

One thing I’m thinking about in all of these stories is how the human cost of war doesn’t change. We may have new ways of fighting, new implements, but there is no soldier who comes home un-scarred. And I think a lot about what that means — and how we could do a much better job of healing the psychological wounds of war — by employing veterans to do work in their communities — it would give them a sense of connection, place and some time to recover. But now, I sound like I’m running for office rather than working as a fiction writer.

Regarding the Jewish holidays, I have always been fascinated by Yom Kippur, and the idea that goes across religions of repenting, or making good, what one has done to hurt oneself, others, and in Jewish writings — even the ideas of what one might do — it goes beyond guilt and into thinking about who one is — the way we move through the world and how our actions and inactions affect the lives of others. Bottom line — that’s what being a writer is all about as well, human behavior in all its inglorious beauty.

We make judgments about whose story is most valid, who has the right to tell the tale.

YC: You have said, in response to this being called a “powerful” book: “Regarding the power of the book — it took a long time and is very much tied to other work I’ve done/been doing, thinking about thinking about the world we live in.” Talk about this more. It’s a compelling statement that feels right with this book.

A.M.: It’s hard for me to describe — except to say we are living in interesting times, the pace of our social, cultural, political world is moving so fast that it is hard to get ones footing. A writer depends on a kind of terra firma — in order to go off screen into the imagination — and know that when one comes back to the surface — things will for the most part be the same. At our current speed of acceleration — one worries that one might surface another (unfamiliar) world entirely. My work is drawn from ideas and ‘issues’ I see before us — history, the forgetting of history, the human cost of war, what one expects of family, of marriage of oneself… in order to explore these ‘non-fiction’ sometimes almost philosophical ideas I have to turn inward — which feels difficult when all one is compelled to do is read/watch the news — as if bearing witness.

YC: Do you think a writer’s past work remains in the DNA of current and future works? If so, which of your previous books or short stories have influenced you the most in writing Days of Awe?

A.M.: The short answer is yes always, as different as each/all of the work is it is part of a progression that in some ways is invisible to others… for example the character Henry Hefelfinger in Rockets Round The Moon, is the early (younger) version of Geordie Harris, in The Chinese Lesson, who is actually an early iteration of Harold Silver, the main character in May We Be Forgiven. So that’s a very concrete example and there are literally dozens of those.

Going back through you can see that my interest in human behavior — why people do what they do — and how it affects them and those around them is at the core as is a kind of morality which I never can tell if I should ‘advertise’… ie what does it mean to be a moral writer — and is that a good thing? I’m not passing judgment on my characters — in fact kind of the opposite — I give them room to expose themselves, to come to know themselves in ways that before we spend time together they might not. Here’s the big reveal — and it’s not about me as a writer — but about an idea that concerns me a lot. People sometimes say, am I supposed to “like” that character…. The notion of whether or not a character is likable worries me, it’s a very-very modern and troubling idea #1 was Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s Raskolnikov likable? Vladimir Nabokov’s Humbert Humbert? And do we want the character to be “likeable” so we can “relate” to them — and can we only see ourselves in a likable person — i.e. we need to be made to feel good about ourselves and our reflection in literature? This to me opens a whole world of discussion and perhaps a course I should teach someday called: I Don’t Like You, I Love You, the problems of Q-Rating Literature.

Do we want the character to be “likeable” so we can “relate” to them? Do we need to be made to feel good about ourselves and our reflection in literature?

YC: This collection represents a faceted diamond in which light and illumination is always possible, even when there is disruption or loss. Can you speak to this?

A.M.: I like your idea of faceted diamond where light and illumination is always possible…that’s lovely. I am always trying to tell the stories of my characters lives, of their experiences and these are in some ways just slices of the fullness of their lives and hope to capture the essence of both what we know and what we don’t know about ourselves, our lives, our histories. And yes, even in disruption and loss I am looking for light — which doesn’t mean dismissing gravity but light as illumination — learning, discovery. I want to remain always curious, engaged, looking and thinking.

YC: In your earlier books, reviewers often remarked about being shocked or surprised by your writing about certain topics that were “haunting, terrifying, twisted, dangerous …” Did you find those descriptors as helpful or too summarizing?

A.M.: Words like haunting, dangerous come easily — but at the same time they’re not very specific and perhaps leave too much room for one to simply project into that word whatever one wants — so I think the more specific one can be in describing something the better — even if one disagrees with it — at least you can understand exactly what the person is saying.

I’ve always been bothered by the idea that that I am writing to shock people — that’s something applied to my work from the outside. I’m writing to tell stories — to illustrate the human heart — and if people find it shocking, well, that means it hit a nerve, but I don’t set out to shock or disturb. What happens in a career that spans quite a few years is that reviewers go back and they don’t read the past books — they read the reviews, and they bring those misconceptions forward and apply them to new material, so it’s hard to escape.

YC: Who are the emerging writers that you’re reading?

A.M.: I’m very involved with my students and what they’re doing and I do a lot of things like judging for awards and Granta’s Best Young American Novelists. I’m always reading, always looking at all kinds of things, newspapers, books, photographs — and I love hearing about and reading new writers.