Interviews

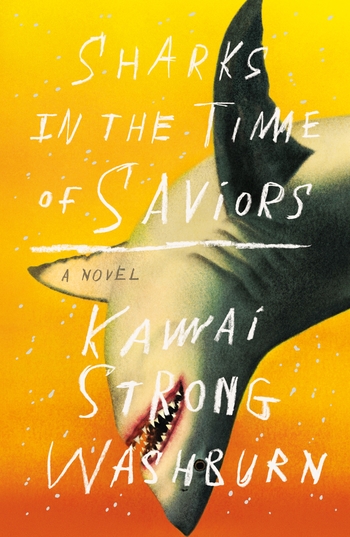

A Magical Realist Novel Inspired by Hawaiian Mythology

Kawai Strong Washburn's "Sharks in a Time of Saviors" is a family saga about working-class islanders struggling to make a living

In Kawai Strong Washburn’s Sharks in a Time of Saviors, a young boy falls into the ocean and is carried by a shark—in its jaws—back to his mother. The boy, Nainoa, soon begins to display miraculous healing powers.

But he’s been touched by Hawaiian divinity from the very start of his life. On the night of his conception, which opens the novel, his parents see the Night Marchers, the spirits of ancient Hawaiian warriors. Nainoa’s supernatural abilities shore up the family, who had been hit by the collapse of the sugarcane industry, for a while. Eventually, economic realities force Nainoa and his siblings to leave for the mainland for school and work prospects.

Washburn, who was born and raised on the Big Island, offers a Hawai’i that takes in its technicolor-saturated vistas: “And there was the Waipi’o Valley: a deep cleft of wild green split with a river silver-brown and glassy, then a wide black sand beach slipping into the frothing Pacific.” Equally, he renders the precarities of paradise for Hawaiians through the family’s continued struggle to survive.

I spoke to Washburn about saviors, deeply-in-love PoC couples in fiction, and the prospect of another Hawaiian son, Barack Obama reading his novel.

J.R. Ramakrishnan: I must say that my reference points for Hawai’i are woefully limited to watching reruns of Magnum P.I. in my teens dreaming of the beaches. Also then more recently, Barack Obama, of course. So you were born in Hawai’i?

Kawai Strong Washburn: Born and raised! I was born on the Big Island. In fact, I spent the majority of my youth in Honoka’a where the book begins. It’s actually my hometown.

JRR: And your family’s roots are indigenous Hawaiian?

KSW: Actually, I’m a lot more like Barack Obama like that. My mother is African American. She grew up in Kansas. My father is, I guess you could say, is European American. He grew up in Oklahoma. Both moved there for school. They met, got married, and decided to stay there to raise a family. So I’m not actually native Hawaiian ethnically. I am local to the island. I spent all my formative years there.

JRR: You open the book with quite a spectacular scene of Noa’s conception in a truck and the Night Marchers. How did the novel’s story come to you?

KSW: The opening image was the one that just showed up in my head one day. I don’t know what made it happen. At the time, I was working on short stories and I didn’t see it as being something that I was going to turn into a novel and so I just let it fall away. It kept showing up for about a year and a half. So I finally started thinking about it: what is this image of a child being pulled from the water by sharks? For me, when I think of children, I think of the family naturally as an extension. I started wondering, where’s the family? The questions I started asking about the family, as well as, the image itself—–why were the sharks carrying the child?—–started to build parts of the story. Once I had some ideas about who that family was, I really started digging into them, and into some of the mythology that might explain why a shark might save a child.

JRR: Could you talk about the mythology that informs the novel, and perhaps in particular, the Night Marchers?

KSW: The mythology of the island is something that I have carried around subconsciously. A lot of it was floating around in me and I had a partially remembered knowledge of it from growing up in Hawai’i. One of the strongest recollections was the Night Marchers. My understanding of it as a child was that they were very specific to Waipi’o Valley, which is the valley that you see in the novel. It turns out that they don’t necessarily have to be specific to that valley or that place.

The idea of tying the Night Marchers to Nainoa and with what he represented came out later in the revision process as I was trying to get a better understanding of what tied the family together and of the questions about heritage, and the relationship between the family and the land. I started to recognize different ways in which the characters experience the voice of the land.

One of the things that novel subtly, maybe not so subtly, I’m not sure, questions is the idea of a singular savior, who would be the way out of difficulty. I knew the novel was going to be about that and I knew Nainoa would represent that flawed idea of this great man theory of history. What would it look like then if the powers that he has were to be present in the other members of the family but they may or may not be conscious of them? That was sort of where I started getting the idea about how the different characters experience the stuff that Nainoa experiences and their journey to understand these powers.

JRR: I adored the portrayal of Nainoa’s parents. They obviously have to deal with a lot in their whole lives but Malia and Augie seem totally in love. Him always trying to get in her pants is so endearing. I don’t know if we see many loving relationships (untouched by deep dysfunction in themselves) between PoCs in fiction too often.

I wanted to show a side of Hawai’i that people might not be familiar with, the economic challenges for people that live there.

KSW: That was really important for me. I wanted to show a side of Hawai’i that people might not be familiar with, and I think a lot of people that visit the island might not realize the extent to which it is an economic challenge for people that live there. Most have to string together two or three jobs, drive really far to do them and a lot of jobs are tough, service-oriented ones. Poverty and economic struggles were important to talk about, but I wanted to balance it so the novel wasn’t entirely bleak.

People of color and families in poverty are constantly depicted as dysfunctional. Because they’re in poverty, they must have poor relationships. That’s certainly nothing like what I had experienced growing up in the islands, which is really that you can even have a certain level of, I don’t want to say, thriving, but you can reach a level of happiness and contentment, even in economic precariousness. I wanted to depict that, to have families know each other very deeply and especially the parents. The source of their resilience is that joy for each other and their very physical joy for each other.

JRR: I want to ask you about the landscape because I feel that is perhaps the main reference point of Hawai’i for people not from there. I thought you did such a tremendous job of rendering the environment in the novel.

KSW: At one level, I wanted to describe what I had felt when I’ve gone on hikes in the remote areas or when I was surfing and hovering about the reef in the current. I wanted to write about all the different experiences I had growing up in the natural environment, and how singularly transformative it all felt. I also wanted to figure out a way to describe the islands in a way that almost personified the landscape into a character in the novel. The idea was to build a physical presence that was tactile for the reader, which also reinforces the characters’ relationship with the land.

JRR: Can you recommend some books about Hawai’i that you think I should read to cover my unfortunate gap in the Hawaiian part of American literature?

KSW: The first author I encountered as an adult searching for stories about the island was Lois-Ann Yamanaka. She has written novels, short stories, and poetry. Look for Saturday Night at the Pahala Theater, Blu’s Hanging, and Wild Meat and the Bully Burgers. Kiana Davenport’s Shark Dialogues, which is the start of a trilogy. Kristiana Kahakauwila’s short story collection, This is Paradise. For Hawaiian mythology, there are the books of Martha Warren Beckwith.

JRR: Do you think Barack Obama has read your book yet?

KSW: That’s a scary thought! I don’t know. He’s so well-read. The book’s had a certain amount of visibility. I have a feeling it will probably be on his radar at some point. He’s so well-read and I appreciate his taste. He’s also from the island, which makes it an even more daunting prospect that he might read my book! It would be interesting to see what his thoughts are, and if it resonates with him at all. I try not to hold out hope or let it keep me up at night.

JRR: In some ways, he’s a bit like Nainoa, isn’t he? He’s from Hawai’i, exceptional, and, I think, some (or many) would say, with special powers too.

KSW: Yes, it’s funny. Like Nainoa, Barack Obama is the sort of character that people on some level ascribe ideas of greatness and larger-than-life saviorship. Given the speeches he’s made and what he’s tried to focus people’s attention on in and out of office, I think he is just an individual who’s trying to accomplish a set of things. I don’t think he’d consider himself that special to think that he’s capable of things that none of us are capable of or anything like that.