Interviews

A Pixies Album in Short Story Form

Claire Rudy Foster's "Shine of the Ever" focuses on the punks, queers, and misfits of grunge-era Portland

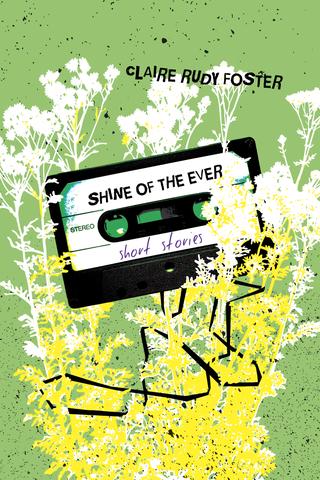

There is a hymn on the first few pages of Shine of the Ever. Claire Rudy Foster writes in “The Pixies”: “When we’re together, we forget that we are hopeless. We are something else and we are part of each other. We will never fit. Why would we want to be like you?…My Velouria. The chorus comes and we are a mass of bliss and fury and love and pain and truth and sound. Finally through the roof. We are going to shake you loose.” This rebellious yet tender, frank yet lyrical yearning is what Shine of the Ever is. A collection of stories for the pixies, the punks, the lovers and the loveless. Shine of the Ever has the image of a mixed tape as its cover art but I want to call it a hymnal, a psalm, for those who have wanted to see themselves in fiction and felt ignored for way too long, for those who are ready to shake loose of the traditional constraints of society and literature.

In thirteen stories, Shine of the Ever is a collection of narratives with queer characters navigating Portland, Oregon—the city a character itself. Each character is searching for a sense of understanding and human connection while they continue the work of figuring their own selves out. What is special about this collection is that each story ends not on the stereotypical dreadful tone most stories about queer characters have. In Foster’s narratives, no one ends up punished for the way they live their lives. But rather, each story ends with a hint of hope, a sentiment very much needed in this era of Trump and the all out attack on LGBTQ+ civil rights.

Claire Rudy Foster is a queer, nonbinary trans writer who lives in Portland. Foster is the author of the short story collection I’ve Never Done This Before. Their writing has appeared in The New York Times, The Washington Post, The Rumpus, McSweeney’s, and elsewhere. Foster has been in recovery from alcoholism and addiction since 2007, and co-authored American Fix: Inside the Opioid Addiction Crisis and How to End It with activist Ryan Hampton. Their contributions to the recovery movement include speeches, letters, and articles and the recovery podcast “Addiction Unscripted.”

I spoke with Foster about why Portland is a popular place to write about, happy endings as a political act, longing and belonging, and if the world is ready for queer stories from people other than cis white men.

Tyrese L. Coleman: Of course, after reading your collection, I listened to the Pixies’ song “My Velouria,” which is where the line “shine of the ever” comes from. It’s funny, I never thought that a song could completely capture the feeling of a collection of stories in the way that this song does.

Claire Rudy Foster: The collection takes place in grunge-era Portland, and the Pixies were so much part of the sound and texture of that time for me. I love their lyrics: “We will wade in the shine of the ever. We will wade in the tides of the summer.” For my characters, as well as the city where they live, it’s the last days of summer: the last days of youth, when everything seems so important and vital and new. They’re all on the cusp of massive, difficult changes, but for the moment—it’s easy living.

TLC: Is this collection a result of the vibe, the longing, in this Pixies song or of Portland or of a mix of it all or something completely different?

CRF: I’ve heard others characterize queerness as a yearning. I connect with that. I often have the feeling of being outside, observing how other people live. I guess voyeurism is a kind of secondhand fulfillment. In Shine of the Ever, I really didn’t want to create another monument to a time that has passed. Portland has enough of those: memorials to the wonderful, weird culture that was pushed out by rapid expansion and gentrification. The narrator in the book’s title story remarks, “I had that feeling I was in a movie set of my own living room, where every object looked exactly like my personal possession but nicer, cleaner, and more appealing. I hate it. These designers put in a lot of effort to make things seem natural, but I think the only people who believe it are the ones who never saw the original. They don’t understand that this isn’t Portland anymore: it’s Portlandia. A theme park of the places we used to love.” Throughout the book, characters experience a longing that isn’t necessarily for another person, but for a moment in time that can never be recaptured. It’s a nostalgia that ripples into the present and continues to inform the things my characters desire, long for, obsess over, and crave.

TLC: You and Mitchell Jackson both write about Portland as this place that has been replaced with a fictional utopian veneer, though you talk about different communities within the city. It strikes me though that you both write about the city with a reminiscing tone—a love for the good bad old days. What is it about Portland that lends itself so well to characterization in the ways you and Jackson have written about it?

CRF: Portland wasn’t really a “city” until 20 years ago. Maybe less: ten. The condos appeared in the early 2000s, followed by an infestation of ampersands. Portland wasn’t always one of New York’s outer boroughs, where people all wear charcoal grey merino wool and drink artisanal lattes. Twee boutiques obscured the existing DIY culture, the punk scene, and the grittier places. Portland’s “charm,” which was played up by travel writers, tourists, and people who’d been pushed out of their own cities by insane costs-of-living. The city’s rapid overdevelopment happened almost overnight: within only 2-3 years, we were overrun by new residents, huge buildings that are out of character with the rest of the architecture, corporate headquarters, more cars on small roads, all that stuff. Institutions protected by money stayed, but the day-to-day stuff vanished. Almost every mom-and-pop store is now a gleaming, white weed dispensary. The landscape here was altered. For most cities, these changes happen slowly, or they already happened a few decades ago. The invasion of Portland is something I’ll never forget.

The “charm,” if you can call it that, is still more reminiscent of a town than a city. It’s a frontier town with a gory history and a lot of problems. There’s rich soil here for writers. Portland’s transformation features prominently in Shine of the Ever. Yet, in spite of these changes, the core parts of Portland remain the same. It’s a small city. The longer you live here, the smaller it seems. I think people write about it because it’s easy to fit it all into one book. It’s a fraction of the size of Los Angeles or New York or Dallas and significantly less socially complex.

TLC: You both also write about the drug epidemic in the city, but again, from different perspectives. You are not shy about writing and talking about your struggles with addiction. While I don’t want to make the assumption that any of the pieces are autofiction, can you talk about how your story influenced the pieces in Shine of the Ever, if they did at all?

CRF: First, I think all writing in every genre is autofiction of some kind. Writers draw from their own experiences, impressions, and sensations. An apple tastes like an apple. An apple that tastes like a pear is invented using the linguistic concepts that define taste, fruit, and eating. I think that, even when someone is writing high fantasy or science fiction, they’re still working within the lines of human perception: the writer, like the reader, is still human.

For Shine of the Ever, I was less concerned with historical accuracy than emotional precision. The book was born from my own attachment to a city that has been erased by time, and from my grief at watching its changes as it slipped away from me. This grief is selfish, of course. Many excellent things have come from these changes. But I think most people have felt displaced in one way or another, forced to start over, or disconnected from community. Displacement is part of Portland’s history: the ultra-white city is built on the traditional lands of the Multnomah, Kathlamet, Clackamas, Cowlitz bands of Chinook, Tualatin Kalapuya, Molalla, and many other tribes. I can complain about Portland changing, but I am not a victim. I am merely inconvenienced. The white presence in Oregon is the result of an ongoing cultural genocide against Native people. The invasion I write about in my book is commercial, not cultural; I think it’s important to acknowledge the larger implications of that.

Heteronormativity erases us. Why replicate a system that wasn’t designed for you?

Addiction is part of more contemporary, urban displacement. Addiction is commercialized; it turns a profit. In my recovery, I’ve had to accept that nostalgia, the chronic and insatiable desire to reexperience the past, can be just as addictive as cigarettes, wine, or opiates. Returning to the same place, song, person, or emotion is not that different from picking up a drink: both of them feel good for a while, and they enable the person to depart from the here and now. Shine of the Ever was an indulgence of my nostalgia. Having written it, I wonder if I’m ready to move on.

TLC: The fact that this book has no sad endings is a political act. A political act as a commentary on what people think a queer story needs to be about and also a literary political act because, as we know, capital “L” Literature means sad and depressing.

CRF: If literature is synonymous with sadness, we need to change what literature means! One of the things I love about other genres—because, let’s be real, literary fiction is a genre, just like romance is a genre—is the joy and playfulness I read in them. My favorite authors, like Richard Chiem, Katherine D. Morgan, and Sam Hooker can make me laugh. It’s not hard to make a reader cry, but laughter is so much more intimate. When I was writing Shine of the Ever, I could easily have fallen into tropes and stereotypes that enact violence on the queer and trans body, especially in communities of color. I didn’t want that. I don’t want that for my characters. I thought to myself, “Fuck it. This is my city, my book, and my story. I can do whatever I want.”

The fact is, I’m a white nonbinary trans person who came out later in life. I’m 35, which is older than the average life expectancy of a black trans woman. I’m insulated by privilege in a liberal, predominantly white city. My transition, coming out as trans, all that stuff—it’s been hard. Devastating at times. But my problems weigh less than a grain of the struggle that many other people face. In my book, I give all my characters access to the same privileges I’ve had. Not all my characters are white. Not all of them are solidly middle class. They encounter issues with housing and income stability, access to medical care, real-world problems. But they are not in danger, as queer and trans people are often endangered in popular media. They have the luxury of making mistakes with minimal consequences. That’s freedom: to fuck up and be able to walk away intact. Or, as many white people do, fail up from their mistakes.

TLC: This book provides a counter narrative to the traditional queer “struggle story,” stories that are based on stereotypical struggles that marginalized groups face. A queer struggle story may involve some aspect of homophobia, self-hatred, tense family relationships, or the whole narrative would surround the protagonist coming out. Contemporary literature is shifting away from the struggle narrative—the kids have all come out if they want to, no one has time for homophobic people in their lives, etc…

But though I feel like your stories did not contain the traditional struggle narrative, I did notice that many of your characters still suffered with insecurity associated with their identity or sexuality or love life, a sense of unease and lack of trust. Where does the insecurity come from once we’ve gotten past the “struggle?”

CRF: I don’t think the struggle has changed, but the way we’re centering the queer experience has. Our voices are being heard because so many people, primarily queer and trans people of color, have led the way for trans rights. We have the right to be human and the right to be heard. If I have a voice, if I’m able to name myself on the cover of this book, I owe it to these elders and activists. The courage I have is a gift from them, and I try to live up to their generosity in my work.

Nobody’s safety should depend on whether we are lovable, appealing, or palatable. We are worthy of respect because we are human beings with equal rights.

Identity is a process of becoming, not of arriving. Practicing and experimenting with identity, gender expression and presentation, all those things—that’s a privilege. Coming out is always hard. Dealing with transphobic family members and friends will always be heartbreaking. There’s no way to eliminate those experiences, though I think we’re getting better at supporting people as they go through vulnerable transitions. I can’t speak for the entire community; in my experience, every challenge has another one after it. It’s heavy surf. You are never fully “safe,” and that insecurity can affect the happiness you have in the moment. The problems that LGBTQ people face can be blatant or they can be concealed in language or gestures. In either case, proximity to privilege determines how much systemic discrimination a person experiences. Struggle is relative: my writing attempts to dignify those struggles and weave them into daily life, which is how I encounter them.

TLC: There is also this theme of an “outsider” falling for someone who appears to be an “insider.” For example, in “Domestic Shorthair,” Amit, a nonbinary police tech deals with the unrequited love for a straight roommate. Amit is insecure, is not dealing with the trauma and sadness from their job, and is not able to maintain a relationship past dating whereas their roommate “knew how to work it.”

I use these terms loosely, but I’ve used the word “longing” multiple times in this interview and for me this is really what a lot of this collection is about: a longing for understanding, a longing for love, a longing to be seen. And then I think about the queer community and the continued fight, or longing, for equal and basic rights. What are the parallels here? The longing of your characters who appear to be on the “outside” and the longing for a community who wants inclusivity?

CRF: I’ve been out as queer since I was 15. That’s not new. However, I often felt like my identity was obscured, or reflected back to me in a way that was distorting and cruel. For me, my shame around my queerness was expressed by that longing. Like you said, the longing to be known. The refrain of those earlier years was, “Am I good enough yet? Do you love me yet?” I felt like I would never belong and that part of me would always be unacceptable. When I got older, I learned to give that love to myself—and found a community that accepts me unconditionally, too. Outside those spaces, my safety, individuality, security, and agency are all entirely dependent on whether cisgendered people tolerate me, or heterosexual people choose not to hurt me. The longing I feel now is not for myself, but for social justice. My safety, nobody’s safety, should depend on whether or not we are lovable, appealing, or palatable. We are worthy of respect because we are human beings with equal rights. We shouldn’t have to translate ourselves to those in power in order to earn our humanity.

Amit is on the cusp of that discovery. They don’t have the language yet to describe themselves. They are afraid to name their desires. They seek security in invisibility and gather crumbs of love. They are not ready to take the lead in their own life, and they won’t be happy until they become brave enough to claim it.

TLC: But it turns out that Amit’s roommate doesn’t have it all together, doesn’t know how to work it as well as Amit thought.

CRF: Yes, she’s a hot mess! Amit’s roommate is the closest person Amit has, but she’s not a model for how to live. She enjoys her relative social and sexual privilege. This juxtaposition demonstrates how ludicrous I think it is for queer and trans people to deliberately mimic cishet power structures—and why I think allies are important, but not an intrinsic part of our community. Heteronormativity erases us. Why replicate a system that wasn’t designed for you?

TLC: Do you feel as though the lit world is finally ready to embrace queer stories that are not by and about cis white men? What stories do you hope to see? Who are you reading?

CRF: I hope so, because there are plenty of us with things to say. Cis white men can be great, in their time and place, but the world is so much bigger and more interesting. I hope to see more work from queer and trans people of color, especially stories that center queer joy. I’m reading Everyday People: The Color of Life, an anthology by editor Jennifer Baker and really enjoying it. Trevor Ketner recently gifted me a beautiful copy of their chapbook White Combine: A Portrait of Robert Rauschenberg.

TLC: Your next book is going to be a memoir. Please tell me about it. Will it intersect in any way with Shine of the Ever?

CRF: My memoir, Mom-Binary, is about transitioning through my second adolescence as my son goes through his first. It includes some of the themes, landscapes, and voices from Shine of the Ever and will have excerpts from some of the essays I’ve published in The New York Times, Narratively, and other places. In a way, this book is also about queer victories. I have survived so much, and I refuse to let that trauma define me. Fuck no. I’ll define myself. Mom-Binary is about the reckoning of identity and the process of falling in love with being who you are. I hope you’ll read it; it’s very close to my heart.

Before you go: Electric Literature is campaigning to reach 1,000 members by 2020, and you can help us meet that goal. Having 1,000 members would allow Electric Literature to always pay writers on time (without worrying about overdrafting our bank accounts), improve benefits for staff members, pay off credit card debt, and stop relying on Amazon affiliate links. Members also get store discounts and year-round submissions. If we are going to survive long term, we need to think long term. Please support the future of Electric Literature by joining as a member today!